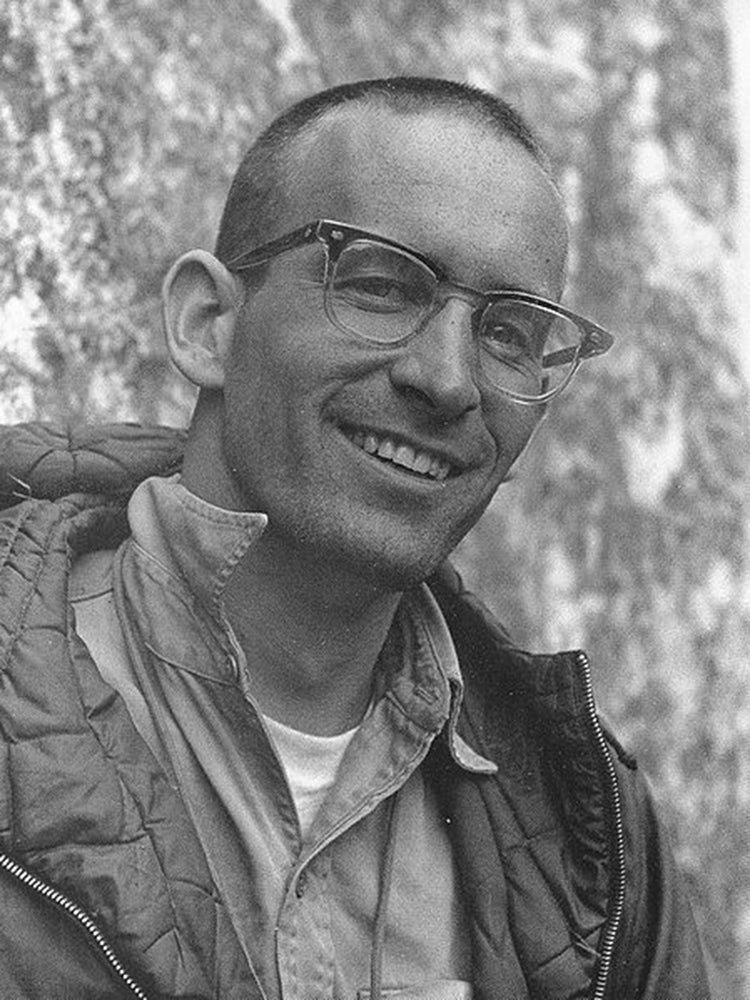

If you've ever been to Yosemite, you've probably seen Royal Robbins' work. Robbins shook up American climbing in the 1950s and 60s with his bold first ascents of Valley landmarks like Half Dome's Regular Northwest Face and El Capitan's North America and Salathé walls. In between, he found the time to build a multimillion-dollar with his wife, Liz, and make first descents around California as a whitewater kayaker.

It's a life story that could fill volumes, and that's exactly what Robbins, now 75, plans to do. In an in-progress series titled , Robbins traces his trajectory as an adventurer from his early childhood in Los Angeles through his later career as a climber and boater. The first book in the series, , was released last September through , and pairs stories from Robbins' school days with an account of his 1963 solo of Yosemite's Leaning Tower.

Speaking by phone from his home in Modesto, California, Robbins told us about his memoirs, the climbers he admires today, and why he believes harder is better.

Adam: The second book in your memoirs is scheduled to be released this fall. What will it be about?

Royal: The second book is called Fail Falling. It's about climbing in southern California, mostly, in the 1950s, and it ends with the first ascent of the face of Half Dome.

A: It should be exciting, if your first book is any indication. Your adventures actually started way before you began climbing. We read about you as a child, jumping between trains and running into pedophiles while hitchhiking. It seems very different from the way children grow up now.

R: Well, Yvon Chouinard told me he encourages his children to eat off the floor, to build up immunities. I think there's a lot of concern about safety.

A: Are people today too paranoid about risk?

R: I think the concern about safety is very good for those who are responsible for others. I think we're overdoing it a little bit in terms of being on the receiving end. On your watch, you never want anybody to get hurt, and I think we've gone a little too far that way, that's all.

A: Do you still climb these days?

R: At the climbing gym, mainly. I get out a little bit.

A: I imagine that writing your memoirs, you've spent a lot of time looking back over your career as a climber. Out of all the routes you've put up, if you had to pick the one you're most proud of, which would it be?

R: There's no question. If I had to pick one, and I could only have one, it would be the Salathé Wall, the southwest face of El Capitan. I'd have to pick it for the adventure, and the most beautiful. It has the best combination of excellent rock, very good problems to climb, good view, and good bivouac sites.

A: You're well-known as one of the first advocates of what's now called “clean climbing,” and were one of the first to refuse to use fixed ropes on a lot of your climbs. How did you come to possess that ethic, when a lot of other climbers were still fixing their ropes and leaving behind pitons and bolts?

R: I think that we were drawn to our ethical stance because it was harder that way, frankly, and I think whatever's harder has to be better. That's why I have so much respect for free-soloists these days.

A: Are there any routes you wish you could have climbed?

R: I wish I could have climbed the north face of the Eiger in Switzerland and Mt. Everest in China. That would be the frosting on the cake, so to speak.

A: That's a lot of frosting.

R: Yep.

A: What do you think of the way that climbing has gone in the US since then, with the advent of sport climbing and rap bolting?

R: Well, I'm not sure, but the impression I get is that the pendulum is swinging back toward adventure. The pendulum swung in the direction of control and safety, and now it's swinging the other way. It's more today as it was when we were following our ideals in the past. I have the impression that we're moving away from pure sport climbing, and more into taking risks and what's harder

A: People used to talk about “conquering” mountains, like they were beating them into submission. As climbers have moved towards alpine-style ascents and not using fixed ropes, it seems like we're hearing less of that. Do you think that climbers' mindsets have changed?

R: That's a good question. I noticed in the paper the other day there was some talk about climbers having “conquered” a mountain. And I was thinking well, that's old stuff.

It's all because of what goes on inside of you. Whether you conquered a mountain or conquered your weakness, I think that you can think of it either way. It depends on the climber.

The reasons to climb something are one, because of what it does to you inside, two, to earn the respect of who you respect, and three, to do it first, if possible.

A: Is there a wrong reason for wanting to climb something?

R: Gee, I hadn't thought about that specifically. I suppose there is, just as there's a wrong reason to do anything. But the reason is beside the point. The performance is what counts.

A: Speaking of performance, you're quite legendary for your insistence on style. Can you share a little of your philosophy with us? Why is it not enough to just make it to the top?

R: I got that from the outstanding climbers of the past, like Walter Bonatti, who were less concerned about getting to the top and more concerned with the way you did it. And that became my raison d'etre for climbing. I tried to be as close to the people I respected in the past as possible by the way I put up routes in the present.

A: Are there any young, active climbers who you have particular respect for, or who you think are going to be the next ones to advance the sport?

R: Tommy Caldwell is very much up there, and also Alex Honnold, who made the first free solo ascent of Half Dome. That's a pretty good step up.

A: Do you see yourself in them at all?

R: No, I don't, they're just doing things I wish I had done. Or could do. They're so far out there it just amazes me. As I say, many of the things that are being done today were clearly impossible in our day. And they're doing them.