JUNE 27, 1970. Two Tyrolean brothers, Reinhold and Günther Messner, stand atop 26,660-foot Nanga Parbat, in Pakistan’s western Himalayas. Having snatched the first ascent of one of the biggest alpine walls on earth, the 14,763-foot Rupal Face, they shed their frozen felt mittens to shake hands and embrace.

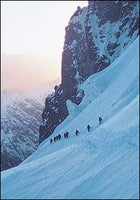

Porters descending from Camp 2

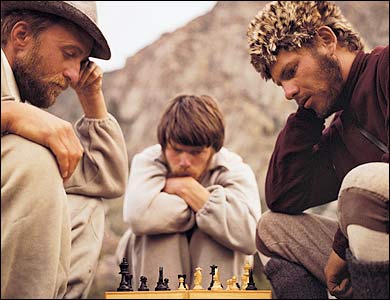

Porters descending from Camp 2 Günther Messner on Nanga Parbat, June 1970

Günther Messner on Nanga Parbat, June 1970

But things turn bad when they start down. Günther, 24, has followed his brother to the top despite the 18-member team’s plan for Reinhold, 25, to summit alone. Exhausted, he develops altitude sickness and, because neither brother has a rope, cannot descend by the same steep route. They blunder down the west side of the peak, succeeding only in cutting themselves off from the Rupal side entirely. After a bivouac near 26,000 feet, Günther becomes delirious. Seeing two teammates, Felix Kuen and Peter Scholz, ascending the Rupal Face, Reinhold cries for help—but they are too far away to understand his pleas. So the brothers make a life-or-death decision: They will head down the opposite side of the mountain via the less steep, but unexplored, 13,300-foot Diamir Face.

The epic that ensued—Günther and Reinhold’s two-day descent down uncharted territory, Günther’s June 29 disappearance in a reported avalanche, and Reinhold’s frantic search of the debris field and grief-stricken escape through the Diamir Valley—is the defining experience of Reinhold Messner’s life, and it’s described in his 40th book, The Naked Mountain, to be published for the first time in English in November by The Mountaineers Books. What U.S. readers may not hear about is the firestorm that the German edition sparked in Europe. In books written as direct rebuttals to The Naked Mountain, two members of the expedition claim that Messner’s story is a whitewash of the truth—that he abandoned his brother on the peak.

“There is a big lie behind Reinhold’s story,” says Hans Saler, a 56-year-old mountain guide now based in Puc—n, Chile. In his June 2003 book Between Light and Shadow: The Messner Tragedy on Nanga Parbat, he claims Messner sacrificed Günther for his own ambition, an allegation echoed in The Traverse: Günther Messner’s Death on Nanga Parbat—Expedition Members Break Their Silence, by fellow team member Max von Kienlin, a 69-year-old baron who lives in Munich.

Both climbers say that Messner’s descent of the Diamir Face was not an emergency escape—that, though this was his first Himalayan expedition, he planned all along to traverse the entire mountain solo and score a first on an 8,000-meter peak. Most astonishingly, both claim that Günther never accompanied Reinhold down the face at all. Instead, von Kienlin and Saler maintain, Reinhold left his brother near the summit to find his own way down, and Günther died descending the Rupal side, alone and unseen. Messner, they say, has been changing his story ever since to deflect his guilt.

This bitter controversy began when The Naked Mountain hit German bookstores in February 2002. Angered by Messner’s portrayal of what happened on Nanga Parbat, the world’s ninth-highest peak, and by his claims on German radio and TV that the team didn’t bother to search for the missing brothers, Saler aired his long-simmering grievances in an open letter to Messner circulated on the Internet and published in German newspapers.

“In your book you play brilliantly on the keyboard of self-pity,” he wrote. “Everybody kept silent about what had actually happened on the wall. Our silence had to do with loyalty, a foreign word for you. You are an excellent climber, but a good comrade? NO!”

“For years we talked to nobody,” Saler told ���ϳԹ���. “I didn’t even tell my wife. I wrote my book so Reinhold’s untrue story doesn’t go into the annals of alpinism without criticism.”

Such charges have brought thunderous denials from Messner, now 59 and a Green Party member of the European Parliament. “Can you imagine I would leave my brother?” he says from his castle home in northern Italy. “This is crazy. It is a lie.”

Charging libel and defamation, Messner has hired Hamburg-based lawyer Matthias Prinz, whose clients have included Princess Caroline of Monaco and actor Don Johnson. On July 14, Prinz’s firm persuaded a Hamburg court to impose an interim injunction against Saler and von Kienlin’s German publishers, halting reprints or translations, though they can sell remaining stock.

The ban is based on 13 disputed statements in von Kienlin’s book and 11 in Saler’s, but the debate is likely to explode beyond those points as civil proceedings unfold in Hamburg this fall. Von Kienlin says that he himself helped Messner concoct the tale of the avalanche, and that he will produce a 1970 diary entry in which he recorded Messner’s emotional confession that he lost Günther high on the mountain. Messner insists that forensics will prove the diary is a fake. Portraying von Kienlin as a failed gambler looking to make back his lost family fortune with a bestseller, he cites a different reason for the attack: “Von Kienlin lost his wife to me in 1971.”

That part, nobody disputes. Ursula Demeter was married to von Kienlin when Messner moved in with them after the expedition to recover from the amputation of his frostbitten toes. She left von Kienlin and became Messner’s wife from 1972 until 1977. But von Kienlin says he got over that long ago and that his critique is a matter of honor, in defense of those “comrades of the expedition who can no longer defend themselves.” Seven of those team members are now dead, including Kuen and Scholz. According to Saler, who was fixing ropes nearby, Messner said nothing to the two about being in trouble, and after a brief shouted exchange, he waved and continued his traverse.

The feud isn’t the only legal wrangling Messner has had over Nanga Parbat. He and trip leader Karl Maria Herrligkoffer fought in court at least a dozen times after the expedition: Messner sued Herrligkoffer, alleging that his negligence in sending up a botched weather signal rushed the summit bid and caused Günther’s death; Herrligkoffer sued Messner for violating the expedition’s now-expired publishing embargo. Messner’s 1971 book about the climb, The Red Rocket on Nanga Parbat, was ultimately banned in Germany.

Messner has now vowed to return to Nanga Parbat to scour the base of the Diamir Face. If he can locate Günther’s remains, he believes, he can prove his story once and for all. “I must go back,” he says. “There is no other chance for me to save my reputation.”

Messner searched for Günther once before on the Diamir side, in 1971 with Demeter, who remains convinced that his tale is genuine. He was “obsessed with finding Günther,” probing the dangerous icefall for four sleepless days, she said.

Finding Günther’s remains in a churning, 12-square-mile glacier may be a long shot, but Messner is adamant that he’ll comb the valley as early as next summer. Having rejected the use of metal detectors to locate his brother’s crampons (the glacier bristles with expedition hardware), Messner plans to train local villagers to continue his search. “It may take ten years or 30 years, or it may happen after my death,” he says defiantly, “but I must find Günther’s body.”