TO PROPITIATE THE GODS, Sonam the cook lights a sang— a small votive fire of fresh juniper bows sprinkled with buckwheat flour— as soon as we reach camp. The smoke purls up like a blue ribbon between the wet, black canyon walls while Sonam says a prayer. Jon Miceler, a tall, bespectacled reed of a man in a conical Asian hat, and I stand in the muddy yak meadow, watching from beneath sodden umbrellas.

It has been raining ceaselessly since we began the trek five days ago. This may be a sign from various tutelary deities that we are unwelcome here.

“No cheelips [foreigners] have ever entered this place,” says Sonam, perhaps implying that Jon and I, two American travelers, are interlopers who could be responsible for distressing the gods inhabiting this Himalayan valley deep in northern Bhutan.

Earlier today, hiking through a narrow gorge on a trail so heavily overhung with flowering rhododendrons that it was like a secret passage, we stopped at a chorten, a primitive Buddhist shrine, in the forest. A moss-covered cairn topped with a faded prayer flag tied to a branch, it had been carefully garlanded with flowers by passing nomads. Sonam collected a handful of fuchsia blossoms and placed them at the base as an offering. When I asked him why he’d done this, he shrugged. Later, walking a crooked path carpeted with rhododendron petals, he whispered that we needed protection as we entered the sanctuary of the mountain gods.

The rain douses the sang, but our group—Jon and I and seven Bhutanese support staff—is already ensconced inside several nomad huts. They are crude, built of stacked river stones with a roof of planks split from a nearby tree. You crawl in through a hole in the rocks. Inside, there is a fire pit and fir boughs spread over the dirt floor. The leaking roof is so low you have to crouch, and the boughs are infested with fleas. Still, once a fire is crackling, it is a warm, snug shelter.

During the night, the rain stops for the first time in nearly a week. We awake in a different world, almost as if we’ve passed through a sacred portal. On both sides of the valley, frosted mountains, formerly hidden by curtains of mist, rise sharply into a cold blue sky. Looking northwest up the valley, we see a sawtoothed spine of brilliant white. Jon and I scramble up the side slope to get a better view.

The spine, one valley west and still at some distance, is the east ridge of the highest mountain in Bhutan and the highest unclimbed peak on earth—Gangkar Punsum. Its immensity is staggering: 24,742 feet of intimidating, swordlike artes. Gangkar Punsum is home to one of Bhutan’s animistic gods, and it has a fierce, even savage, visage. The summit is not a benign dome but a point of frost-blue ice as threatening as the thunderbolt of Channa Dorji, Tibetan Buddhism’s wrathful deity of power.

“No wonder it was never climbed,” I say.

“And never will be,” Jon replies. Gangkar Punsum lies on the border of Bhutan and Tibet, about 300 miles east of Mount Everest. At least four expeditions attempted it in the mid-1980s—Americans and Japanese in 1985, Austrians and Brits in 1986—but all failed. The American team, which included Rick Ridgeway, Yvon Chouinard, and John Roskelley, was stymied by bad directions and did not even reach base camp. Then, in 1987, following reports from villagers that the gods, furious at this trespassing, were taking revenge by sending crop-flattening hailstorms, Bhutan banned mountaineering across the kingdom. To the Bhutanese, mountains are sacred citadels, no more meant to be climbed than the dome of the Sistine Chapel or the minarets of Mecca.

Jon Miceler and I had come not to poach the peak but to pioneer a route along its southern flank. Jon has studied Buddhism extensively and was based in Asia for eight years. He speaks and reads Chinese and Tibetan and knows more about the fantastical, complex history of the various forms of Himalayan Buddhism than anyone I’ve ever met.

Jon owns High Asia Exploratory Mountain Travel Company, an outfitter that guides custom expeditions throughout China, Bhutan, and India. He is also the founder of Inner Asian Conservation, a small NGO devoted to wildlife conservation and helping governments develop sustainable methods for managing tourism and trekking in the last pristine places in the eastern Himalayas. His conservation work in Arunachal Pradesh, India, was recently awarded a MacArthur Foundation grant. Jon had been invited by the government of Bhutan to scout a route to the base of Gangkar Punsum from the southeast; the goal was to determine the feasibility of creating a Himalayan haute route that would traverse directly below the peak, perhaps eventually connecting to Bhutan’s epic, 25-day Snowman Trek.

We stare at the craggy hulk of Gangkar Punsum until, inevitably, clouds begin to engulf it. First the summit disappears, wrapped in a white scarf, then the adamantine shoulders. Soon the mountain vanishes altogether.

BHUTAN IS A MOUNTAINOUS kingdom the size of Switzerland, in the heart of the Himalayas. Bordered on three sides by Indian states—Sikkim, Assam, and Arunachal Pradesh—and by Tibet to the north, it remains one of the most inaccessible countries on earth. There is only one airport, in Paro (just west of the small capital of Thimphu), served by one airline, Druk Air, and only one narrow, twisting highway that crosses the country from west to east.

Until the early 1970s, Bhutan, a nation of roughly 700,000 people, existed in self-imposed, self-contained isolation. The Bhutanese bred their own animals and wove their own clothes. Serfdom was abolished only in 1956. There were no paved roads prior to 1961. The first bank was established in 1968; before that, the Bhutanese bartered. In 1999, the government ban on television was reluctantly lifted.

The state religion is Mahayana Buddhism, a form deeply tuned to ecological balance. In dramatic contrast with the rest of the Himalayan plateau, almost 75 percent of Bhutan is virgin or reclaimed mixed-tree forests, and roughly 25 percent of the nation has been designated as an ecological preserve of some kind. Clear-cutting and hunting are banned; fishing is severely restricted. In 1995, Bhutan’s National Assembly passed a resolution declaring that the “country must maintain not less than 60 percent of the Kingdom’s total area under forest cover for all times to come.” In 1999, almost 10 percent of the landmass was officially protected as a system of “biological corridors.” In sum, Bhutan is one of the most environmentally progressive countries in the world.

This commitment to ecology is matched by a thoughtful concern for human well-being. In the late 1980s, Bhutan’s leader, King Jigme Singye Wangchuk, 47, declared that “gross national happiness is more important than the gross national product.” The GNH concept was adopted as government policy and described in a 1999 report as something that “cannot be found in the conventional theories of development, [but something that] resides in the belief that the key to happiness is to be found, once basic materials have been met, in the satisfaction of nonmaterial needs and in emotional and spiritual growth.”

Although a number of travelers penetrated Bhutan over the past few centuries, including several British botanists, official tourism didn’t begin until 1974. Fearful of the backpacking counterculture that was quickly Westernizing Nepal, the Bhutanese originally set an annual quota of just 2,000 visitors. Today the government keeps tourist numbers low by pricing excursions into the country well above a shoestring traveler’s budget. Foreign visitors pay a minimum of $200 a day for meals, lodging, guides, and transportation, 35 percent of which goes to the government as a tourism tax. Only about 7,000 travelers visit Bhutan each year, most of them on packaged bus tours. Fewer than 1,000 are trekkers.

Jon managed to obtain our permit because Bhutan’s Ministry of Tourism recognizes the popularity of trekking and, in a country where the per capita annual income is roughly $365 and 85 percent of the citizens are still subsistence farmers, also recognizes the potentially low-impact, high-revenue economics of hinterland travel. That is, as long as adventure travel doesn’t deleteriously affect the sacred traditions of Bhutan.

WE START OUR TREK in the central province of Bumthang, with nine fit, woolly horses; three very old muleskinners in ragged ghos, with the sort of seamed, sun-burnished faces you can find only in the high mountains; three young camp cooks; and our wiry, ever-helpful guide named Karchung.

None of them have ever been where Jon and I want to go.

After our first glimpse of Gangkar Punsum, we hike to the head of the valley, setting up tents in freezing sleet at 15,000 feet. It’s a barren place. Giant slopes of gray rock rise into clouds on both sides. The dirty snout of a glacier can be seen up-valley. Only to the south is there the welcoming green of life. br.

At this altitude, our team has become tremulous and agitated. Karchung has blistered feet and insomnia and can’t eat. The cooks have altitude headaches and brooding malaise. Jon and I have such impressive cases of dysentery that we’ve each lost ten pounds. Even the pack horses are mutinous.

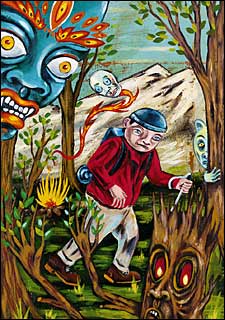

To our companions, these are clear warning signs. Centuries ago, Buddhism in Bhutan became inextricably entwined with prehistoric indigenous animism. Humans have lived here for more than 4,000 years, and the cosmology of Bhutan is populated with more temperamental deities than Italy has long-suffering saints or ancient Greece had mercurial gods. There are specific spirits who inhabit rivers, lakes, and marshes (Lu, Dued, and Tsomen); a deity who inhabits ridges, glaciers, meadows, and forests (Nyen); a deity who dwells on mountain passes (Zhidag); one who lives like a snow leopard in the cliffs (Tsankhang); and the particularly dangerous gods who abide in the white mountains (collectively known as Lha). These divinities are almost all fearsome and vengeful, riding tigers or horses or yaks or snakes, and armed to the teeth with thunderbolts, axes, sickles, and swords.

According to sacred lore, most of Bhutan’s gods were subdued by early Buddhist saints. Some of these native divinities, however, remained powerful and untamed enough to menace humans, particularly those gods who dwell in the mountains. According to ethnologist Christian Schicklgruber, editor of Bhutan: Mountain Fortress of the Gods, “for the peasant population the protection of the mountain gods presents the most important spiritual underpinning of daily life. As long as they receive proper veneration and offerings, these deities guarantee fruitfulness and protection against the powers of evil and natural calamities. But should someone disturb their peace or the requisite offerings fail to appear, they may threaten the livelihood, and even the lives, of their believers.”

After a long night in our desolate camp, Jon and I have a palaver with Karchung. Most of our group is too miserable or spooked to go on; we decide that Sonam and I will continue, while Jon and the others will turn back.

We say goodbye to our compatriots. I take the 1:200,000 Russian topographical maps and Jon lends me his GPS. I have one week to complete the tramontane reconnaissance of Gangkar Punsum and find my way back to civilization.

“Tashi delek,” says Jon—”good luck” in Tibetan—and gives me a hug.

Late that day, Sonam and I cross a 17,300-foot cleft between walls of ice-sheeted rock. There is an ancient cairn, but no prayer flags snap out verses for us. The shrunken carcass of a blue sheep lies in the rocks.

From the pass, I see one black, sawtoothed ridgeline after another. Rows of them, like teeth.

It begins to snow. We laboriously jump talus down into the Mangdi Chu Valley, where Sonam spots, from a thousand feet above, a collapsed stone hut at the end of a spatulate lateral moraine. We arrive just before dark, spread our tent over the windward wall, build a fire inside, and watch it snow from our sleeping bags.

Once again, the sky clears during the night. In the morning it’s so bright I can scarcely open my eyes. I fumble for my sunglasses. Four inches of snow have fallen, and the radiance of Gangkar Punsum is glaring down on us. Sonam slits one eye and instantly crimps it shut. We don’t see the same thing. The immense white face of Gangkar Punsum is merely a mountain to me, a beautiful, inanimate object composed of stone and snow, created by the Indian tectonic plate slamming into the Eurasian plate and governed by the largely predictable rules of science. Sonam sees a living being with capricious supernatural powers. The snow is a bad omen, he says. Gangkar Punsum is angry. “We must leave at once! Go down!”

A heathen mountaineer, I go up, intent on discovering a pass that would connect our new route with the Snowman Trek. Sonam stays by the fire, praying, and waits to see if I’ll return.

Some days in the mountains are so transcendent that you feel you are the luckiest human alive. That was the kind of day I had. Just the snow, the mountain, and me.

Alone, free from the fearful burden of the faithful, I felt myself slip back into my natural agnostic relationship with the world. A warm emancipatory joy welled up inside me; unbound from ancient strictures, I could once again focus on the adventure ahead.

I trotted along the right lateral moraine for several miles. At the glacier I put on crampons, wielded my ice ax, and pushed straight up the middle. I was below the firn line, and all the crevasses were smiling and easy to jump. In the center of the glacier I entered a maze of slot canyons made of pale blue ice. I navigated through sculpted corridors, leapt silver streams, and sidestepped moulins all the way to the base of Gangkar Punsum, where I shot a roll of film of the ice-armored peak.

From there I hooked west, traveling far up a spur glacier. Hours later, I found the pass at over 18,000 feet, a sharp declivity between two minor summits. I was jubilant. And then, instantly, profoundly fatigued.

I sat down and took GPS readings and put an X on the Russian topo. I ate and drank. I stared dumbly at my watch. It was late afternoon. I stared up toward Gangkar Punsum, once again swallowed by clouds. I understood that the retreat was going to be difficult.

I stayed off the glacier, stumbling down the left moraine, often catching myself with my arms just before slamming into glacial erratics. I tried willing my body to do the right thing, but it was spent. I tried staying ahead of the snowstorm, but it laughingly caught up and pissed all over me.

At some point I realized I had gone too far south and would have to cross the Mangdi Chu River to reach camp. I struggled up and down the boulders along the bank, the water bellowing at me, searching for a place to cross in the snowy twilight. Then I mindlessly plunged in. I thought the water would be thigh-deep. When it churned up to my waist, the cold slicing straight to the bone, I focused on one step at a time. Right before the far bank, I stepped into a hole and the frigid water rushed up to my chest and swept me off my feet.

I remember being abruptly lucid, the fog of fatigue and sickness stripped away by the power and paralyzing cold of the water. I remember thinking how arrogant and presumptuous I was to have insisted on pushing alone into these holy mountains. I remember thinking how stupid it would be to drown. Most of all, I remember the deep stab of fear, the conviction that the river was intentionally trying to kill me.

Then my flailing, outstretched fingers grasped an overhanging clump of willows and I barely hauled myself out of the river.

I knew I was mortally hypothermic. My hands and feet were numb and my clothes hardening. I hiked furiously, but it was pitch-dark and snowing heavily. I was lost, and I kept slipping and falling. I could feel the presence of the mountain. It felt alive and malevolent, out to get me.

Until I saw Sonam’s fire.

SONAM AND I EVENTUALLY made it out. In spite of several more close calls—or perhaps because of them—the chance to find Gangkar Punsum’s hidden pass had been a dream expedition for me.

Bhutan is what Nepal must have been like before the rapaciousness of capitalism, what eastern Tibet must have been like before the rapaciousness of communism. With no hyperbole, the kingdom of Bhutan is the most beautiful country in the world.

Back in Thimphu, Sonam told me he would not go into the mountains again. He wanted to open a cybercafé or a pizza joint.