I’VE SEEN MY OLD PSYCHIATRIST TWICE, at a coffee shop in Boulder, Colorado. It’s hard not to notice him, since this is the man who tried to kill me. Or maybe he’s the man who stood by and watched, bemused, while I nearly killed myself with prescription tranquilizers, and then did less than zero to help me stop. Each time he’s bought a morning brew and slumped in his car, sipping coffee and ogling women. It occurs to me that I should walk over and say something caustic. But at that early hour—with me still sick, wheezy, and shaky, three years into my ordeal of psychiatric-med withdrawal—it isn’t worth the effort. He’s who he is, and I’m in hell, and never the twain shall meet.

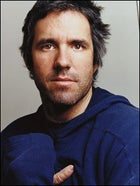

Samet, medication free, in Boulder, Colorado

Samet, medication free, in Boulder, Colorado

Samet, medication free, in Boulder, ColoradoMy name’s Matt, and I’m a recovering addict. I’m 38 and I live in Boulder, where, up until recently, I was the editor of Climbing magazine. I’ve been climbing for 22 years, sometimes at a semi-professional level but mostly just for fun. Still, I love it; I crave it. Climbing is the cause of and cure for all my maladies. It’s the thing that made me obsessive, anorexic, and so anxious that I really thought I needed all the pills—most notably, fast-acting benzodiazepine (“benzo”) tranquilizers like Ativan, Klonopin, and Xanax. Over the years, I’ve shredded body and mind with poisons and palliatives, and sweated out the mess: benzos, booze, marijuana, muscle relaxants, opiates, antidepressants, mood stabilizers, antipsychotics, coffee, sugar, computer games, food, puke, shit, piss, blood. Fueled by my hunger for climbing—and my fear of it—I wanted to drink it all in, to kill the sucking void.

Along the way, I’ve seen the insides of four psychiatric hospitals, starting in 1986, at age 15; been on and off the psych medicines Ativan, Depakote, desipramine, Klonopin, Lexapro, lithium, Neurontin, Nortriptyline, Paxil, Serzone, Trileptal, Valium, Wellbutrin, and Zoloft; and destroyed my car’s steering column and stereo, a countertop, a cell phone, a pinkie finger, and two computers in fits of chemical rage. I’ve also touched heaven—climbed 5.14, scampered across long alpine ridges solo, gone high up and ropeless on finger-ripping overhangs.

Climbing and addiction. Ultimately, they’re the same disease, a singular, brilliant, blood-blasting, pathological breakdown. But here’s the thing: I’m completely sane. I always was. And though I brought my own problems to the addiction party—call it a youthful appetite for too many extremes—it was the benzos that nearly claimed my life.

I FIRST CLIMBED AT AGE 12, in the Cascades with a family friend named Bob, who didn’t mind schlepping an overzealous city kid up the gentle but broken peaks. When I was 15, back home in Albuquerque, New Mexico, my parents—divorced five years but not estranged—transferred me from a cushy private school, where I’d kept finding trouble as a fledgling skate punk, to our district’s central-city public school. As I walked those clamorous halls, with my guard always up, a clutching paranoia set in: With my little mohawk, safety-pin earrings, and bourgeoisie “street smarts,” I was no match for the real toughs, gangs of whom had already jumped us skater kids on the streets. I stopped attending class—my anxiety too strong to overcome—and my parents rebelled at my rebellion. Two weeks inside a mental hospital (and five months as an outpatient) converted my fear into a manageable panic, but I still saw the world as a place of violent, elemental chaos. I began to climb regularly then, through the local mountain club and the outdoor-education arm of the hospital’s Challenge Program. I loved it. On the rocks, the rules were clear and fair, the goals immediate.

Even so, the anxiety never left, and for many years I fed it by depriving my body of food. In my twenties, I wanted to stay skinny for rock climbing because I’d become good enough to aim higher, quickly doing 5.13 and 5.13+ routes. In 1991, I moved to Boulder, the nexus of all things body-obsessed and vertical, and kept to a spartan diet: nonfat hot cocoa, three apples, and 20 saltines per day. I dropped to 125 pounds—this on what was once a stocky five-seven, 165-pound Russian frame. After a year, my heart began to skip beats. With the palpitations came panic attacks, the first one landing me in the ER at 21, in 1992.

The fear hit then: unprovoked fits of hyperventilating, heart-slamming terror arriving randomly from Planet Hell. That’s when I discovered benzos, taking a few prescribed Ativan every month, washing them down with wine when I felt a panic attack coming on. “Don’t take too many,” warned the psychiatrist I saw in those days, a rare benzo-savvy practitioner in a field dominated by pill pushers. “You’ll get hooked.” The first pill didn’t transport me like that proverbial first injection of heroin; instead it brought a fuzzy feeling: All was OK, and even if this “anxiety” did exist, it had no direct bearing.

The doctor had a point, though. Benzos are the world’s most widely prescribed psychiatric medicines, and they’re surely one of the most addictive. They’ve been around since 1957, when the first benzo, Librium, was brought to market. Today, four million people in the U.S. take “therapeutic doses” of benzos every year, with millions more worldwide taking them by prescription and untold millions in Third World countries buying them over the counter. Doctors use benzos to treat anxiety, insomnia, muscle spasms, and seizure disorders. Probably the best-known benzo is Valium, which in the seventies was the most widely prescribed drug in the U.S., followed later by its more potent cousin, Xanax, which debuted in the eighties.

But here’s something the doctors usually won’t tell you, even though it’s stated on the FDA’s Web site: For most people, benzos are OK for only a couple of weeks. If you take them daily for a longer period—especially the newer, high-potency varieties like Xanax, Ativan, and Klonopin—you can easily start a cycle of tolerance, addiction, dosage increases, depression, anxiety, panic, insomnia, and fucked-up, uninhibited behavior, as well as set the stage for a daunting withdrawal. And when the withdrawal comes on fiercely (more about that later), it might best be compared to enduring a bad acid trip while bedridden with avian flu…for weeks, months, even years, often while the very shrink who got you hooked tells you that it’s the return of, as American doctors are prone to argue, your original anxiety disorder.

If you think I’m exaggerating, Google “benzo withdrawal” or “benzo support.” The lore, the books, the forums, and the horror stories are out there, part of a grassroots movement that represents your best hope. The psychiatrists and drug companies won’t help—benzos are too bloody profitable—and hospitals and detox centers won’t do much, either. Most likely, they’ll take you off the pills with criminal quickness and, once your soles hit the pavement, disclaim any lingering effects. I know because it happened to me. I know because, for a run of long and nightmarish years, it took climbing away.

SENIOR YEAR IN COLLEGE, 1996, Boulder: I’ve drifted back to drug abuse after six years of living mostly clean, having given up my high-school pot habit. A buddy knows someone who sells Valium by the trash bag. We keep a bowl on the counter, popping them like after-dinner mints on our way to raves. One night I get so pasted that I dance around a friend’s house, fucking his roommate’s toucan napkin rings. He laughs, but we both know it’s gone too far. I grow disgusted, quitting cold turkey, which is never wise with benzos—psychosis, seizures, and death can result, and you can lay the groundwork (as I did) for more profound addiction and withdrawal later.

“You need to go to Narcotics Anonymous or you’ll just end up back here,” a social worker tells me a few days later. Gripped by Valium withdrawal, I’ve checked myself in to the psych ward at the Mapleton Center, part of a hospital in Boulder. He looks at my discharge sheet, looks at the book in my hand—Camus’s The Myth of Sisyphus—looks at me again.

“I mean it,” he says.

A few weeks later, the worst of the psychosis has passed, and I’m no longer convinced that the Reploids from my Mega Man video game are after me. I spend 1997 sport-climbing with fiendish obsession in the limestone defile near Rifle, Colorado. But then I crumble. Skinny and nervous again, I move back to Boulder, seek out a new psychiatrist—the doctor under whose care I finally come undone—and wrangle a prescription for 30 Ativan a month. This soon becomes 60. From 1998 to 2005, I down benzos every day; during that final year, I ask for more and the doctor ends up quadrupling my dose. The pills take over my body and mind. They slowly strangle my climbing.

But how? I didn’t ask then, because I had no idea—or was not yet ready to admit—that the drugs themselves were causing my problems. Years later, I gained some perspective from Dr. Heather Ashton, a professor emeritus of clinical psychopharmacology at the University of Newcastle upon Tyne, in northern England. Ashton has spent three-plus decades studying these problem pills, developing a withdrawal protocol—switching patients to Valium, a benzo that lends itself to a very slow taper—that has helped thousands withdraw safely.

“Benzos are ‘de-punishing drugs,'” she explained over the phone. “They stop nasty feelings of anxiety and so forth, but they don’t necessarily get you high.” Benzos affect a neurotransmitter called gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), calming the brain’s excitatory action. (In contrast, “pleasure-center” drugs like cocaine work on the dopamine system, leading to the classic addiction model of craving and drug-seeking behavior; benzos rarely cause cravings.) As you become tolerant, your brain compensates by decreasing the number of GABA receptors. With long-term users, Ashton says, “your body is saying, ‘I want more of this,’ so people become much more anxious.” This is known as “tolerance withdrawal.” It’s often accompanied by a subcomponent of interdose anxiety, and it’s only temporarily alleviated by increasing the dose. I hit this stage in just months during that first year of daily use, 1998. But my psychiatrist, who seemed either happy to keep me on the pills or resigned to it, continued to insist that my terror was caused solely by flaring panic disorder. And so it went, me weaving those pills into the fabric of my climbing and throwing in a boatload of pot.

CAN A NADIR ALSO BE A PEAK? Can I confess that the most dangerous lead climb I’ve made—Primate, an 80-foot, nearly unprotected 5.13 in Colorado’s Flatirons done in 2000—was a swindle? Can I admit that, in the awful, stuttering half-hour before I started, I surreptitiously popped four Ativan? That my friend Steve passed me a whiskey flask and I pulled on it, hard, to wash down the pills? Can I tell you that my tallest boulder problem, Chewbacca, connecting 30 feet of crimpy holds at Hueco Tanks, in West Texas, was done armed with two milligrams of Ativan, some Mexican Valium, Carlo Rossi chablis, and a bushel of reefer? Can I tell you that I followed this pattern for six-odd years—that I became adept at sneaking off to the bushes with my little bottle before a dangerous climb (and, let’s face it, climbing, by nature, is mostly dangerous) to dull misgivings and/or tamp down the tolerance withdrawal?

Because here’s the thing: To climb well, you have to be in the moment, the one in which self-consciousness evaporates and only movement remains. Sure, climbing is a physical challenge, but the game is mostly mental, a matter of staying calm enough when facing a fall to execute the next move properly. So that was my little secret: that the zone broadened and deepened with pharmaceuticals. That I was able, by soothing my nerves with benzos, to climb 30, 40, 50 feet above the ground in places I didn’t belong, ropeless on walls of wafer-thin flakes that rang like china with each tentative knuckle rap. That I navigated through a drug-induced fog for a big chunk of my climbing career, even as I left behind a miniature legacy of climbs that most people haven’t cared to repeat.

Off the rock, I tacitly accepted the pills as a necessary evil after two blackly frightening attempts to quit, in 1999. I became more trapped still after moving to Colorado’s Western Slope, in 2002, working editorial jobs at two climbing publications. But it’s still hard to describe the ascendant horror. Maybe it’s that quick gut-jump you feel while running alone on a wind-blasted highland, as a milky sun slips below the horizon. Maybe it’s the closing of dihedral walls 2,000 feet up a monolithic face. Maybe it’s a sort of winking out, the certainty that, close by but in no specific spot, something terrible awaits.

THE LONGER YOU’RE on benzos, the thicker the fog. I recall with a shudder the time in 1999 when I blearily took a friend off belay at an anchor when he hadn’t asked me to, a potentially fatal error that he caught just in time—giving me hell about it, understandably. For obvious reasons, that screwup haunts me, though in the freewheeling climbing community, that kind of behavior barely attracts notice. In fact, it wasn’t until five years later that I was called out.

July 2004. At this point I’m taking three milligrams of Klonopin per day, the equivalent of 60 milligrams of Valium. Two pitches up the airy Don Juan Wall, at the Needles, with California’s sequoia-studded Kern River Valley spinning 5,000 feet below, I decide I’m not up to leading the crackless open-book dihedral before me, so it’s time to descend. Michael Reardon, a close friend and talented free soloist later swept to his death off Ireland’s coast, offers to take over, but I’m done. I lower to his ledge, atremble, and gobble a blue-green Klonopin. “What’s up with that?” he asks, pointing at my hand. I take out the bottle and show him: white label, droopy-eyed icon to indicate soporiferousness.

I tell Michael of my anxiety burden, that my doctor says I’ll need these pills for the duration. He winces, pinned on the wall with a pill popper. Later he’ll tell me, as he watches me struggle to kick the habit, “I had to wonder, with you being a climber. It’s like, ‘Now, how does this work?'”

That September, living in Carbondale, I hit my worst tolerance wall yet, and the psychiatrist switches me to Xanax, four milligrams a day. The interdose anxiety flings me out of bed at 2 A.M., panting and screaming, my skin hot and prickly as if kneaded by angry ghosts. I’m desperately lonely, living solo in an efficiency tacked onto my friend Lee’s house, eating 80 milligrams of Vicodin a day on top of the Xanax to produce a heroin-like narcosis, playing Halo 2 awash in drool. I’m drinking, isolating. I’ve told no one about the true depths—not my then-girlfriend, Kasey, nor climbing partners, nor co-workers, nor Lee, nor my parents. My psychiatrist shifts me back to Klonopin, and the change is too abrupt. Xanax hits GABA sub-receptors that aren’t covered by the Klonopin, and during the two weeks it takes my nerve endings to readjust, the world shimmers with menace. This chemical circus, I’ve come to realize, must stop. I move back to Boulder in June 2005 and keep trying to peel away the drugs.

“YOU HAVE ANXIETY, Mr. Samet,” says the ward psychiatrist, an unsympathetic tub I’ll see just this once. “Why would you want to go off these pills?” It’s September 2005, and I’ve landed in a hospital outside Boulder, seeking help in my struggle to come off the last milligram of Klonopin. This doctor declines to oversee a withdrawal episode, instead prescribing the antipsychotic drug Seroquel, saying this “nonaddictive” med will help wean me from the Klonopin.

But this new junk makes me stupid: fish-gobbed and glassy-eyed. My father—an epidemiologist who’s flown in from Baltimore to help—springs me that very night. Over the following weeks, back home in Boulder, catatonic with withdrawal, I no longer climb.

Instead, the original psychiatrist mixes in other meds to damp what he calls a “raging panic disorder.” I’m on and off different pills as I chase phantom diagnoses, trying demon elixirs like Zyprexa and Risperdal and Depakote that slacken my face to a corpse-like mask and fill my mouth with cotton balls.

The following month, October 2005, my doctor and I up the dose of Paxil, an antidepressant, and I go into serotonergic shock, with its desperate anxiety and myoclonic jerks that kick me inches off the floor. I don’t sleep, even a second, for six days. All these stupid, useless medicines, all this pain.

“Look at this!” I scream at my girlfriend on the sixth night. “Look at these, goddammit!” I’ve taken a steak knife and opened gill-like slits along my hands. I hold up my gift for her. This, I hope, will release the burning within; it’s also a half-assed suicide gesture.

“You need help, Matt.” Kasey’s crying. “I can’t do this for you.” This morning—or was it another?—she drew a bath, set me in the water, brewed tea, hoping these small things would fix me. Now I’ve cut myself and I’m running out the door, planning a leap off the lowly tor of Mount Sanitas. The next day I’m hospitalized again, this time back in the Mapleton Center, the scene of my meltdown ten years ago. I leave after three days. Now, having reacted poorly to Paxil, I’m labeled “bipolar,” coked to the gills on a tripled-up dose of benzos and more mood stabilizers. The withdrawal anguish I feel is labeled a “mixed state”—a combination of depression and mania, the doc tells me.

Bullshit. It’s all bullshit, these psychiatric terms, and somehow I know it. Through a combination of late-night Web research and gut instinct, I’m becoming convinced that what I’m feeling is florid benzo withdrawal complicated by the other medicines. I know that, deep down, there’s an intact person—a rock climber, not a mental patient—even as my psychiatrist insists that none of this insanity could be induced by the benzos, since I’m tapering at a “medically safe” rate.

A month later, just before Thanksgiving, my dad comes to collect me from my Boulder duplex after I crash out while reducing the Klonopin again. I’ve spent two weeks on the floor, sobbing, howling, and clutching my dog, Clyde. He’s a lively Plott hound puppy, but he manifests, in this burgeoning psychosis, as loose skin draped over greening bones. All is corruption; all is death. We fly back to Johns Hopkins, where my father works. Here they will take me off the benzos…very rapidly. In effect, a cold-turkey withdrawal. The final one.

JANUARY 2006: Twenty-seven days off the benzos, back home in Boulder after several weeks at Hopkins. Doomsday weeks spent watching the clock stutter toward each diminishing dose, of being offered a $1,000-per-pop ride on the electroconvulsive table (no, thanks), of staring at the slushy East Coast flurries that spackled my screwed-down window at a time of year when I should have been climbing in the desert.

Kitten-weak in the aftermath, I muster the courage to venture up to Flagstaff Mountain. A collection of red sandstone fins, Flag is a longtime local bouldering ground for me. But that first day I stumble and whirl with mal de debarquement. When my friends look at me, their eyes retreat, snail-like, into bottoming sockets. The world is coming in frames and flashes and a wicked spray of January sun—can no one else see this vulgarity? I shake and slobber and get one foot off the deck. I remove my rock shoes and pretend to sit on a block, hovering in case I decide to flee (to where?).

The first 12 months, I sleep two or three hours a night. My waking reality is one of hallucinations, tremors, anxiety, but much, much more than that—overarching sensations of rushing and poison, an intense agoraphobia. I shop, rapidly, at a 7-Eleven and then work up to run-walking through smaller markets, then to supermarkets. I reclaim the small, simple things: driving, conversing, trying not to feel like every sentence is a misremembered line from a hastily skimmed script. I constantly hear “hell music,” stuff that sounds like vile incantations from evil Chuck E. Cheese animatrons. My hearing and sense of smell are hyper-acute: Dairy products reek sweet and rotten, and anything wooden gives off a welding odor.

Later, I become sicker than ever when I stop the third of three medicines—an antidepressant—they gave me at Hopkins. Nine months post-benzo, my stepfather drives up from New Mexico to collect me, and I spend two weeks poleaxed to his and my mother’s Albuquerque couch in a depressive terror that takes another year to dissolve.

During the first 18 months off drugs, I wake up each morning, spit the blood that’s drained from my overtaxed sinuses, and prepare for the wasteland of 20-plus waking hours. I often dream of climbing, and in those dreams my physical reality doesn’t fetter me. Instead I swarm up the stone or stride easily across a room, not hobbled by a Gollum body locked in muscular hyperdrive.

As I grow stronger, I start walking Clyde for an hour and I play a bit at the climbing gym, but often I’m so short of breath that I have to crawl upstairs. For a few optimistic months, I push through the symptoms to go sport climbing, but my efforts leave me exhausted and demoralized. After one gung-ho day of cragging, I don’t sleep for three days, so strong is the nauseating electrical current coursing up my spine—a nervous system incensed.

In the dead time, I begin to read anti-drug polemics: Toxic Psychiatry, Benzo Junkie, Your Drug May Be Your Problem. The stories on the Web scare me shitless—tales of people still housebound after four years off or still ailing at five. Tales of people handcuffing themselves to the bed so they wouldn’t commit suicide. Tales of madness and seizures, of homes and jobs and families lost, of psychotic suffering and interminable sleepless nights. I obsess over a YouTube video of a man in Texas, taken four months after cold-turkeying his Klonopin. He couldn’t stop twitching, sobbing, and stuttering. One night, I learn, he looked into a mirror only to see his reflection turn wordlessly and walk away.

NEEDING SOME HOPE, I call Dr. Ashton on a bleak December day in 2006 to talk science but also to ask questions: Will I ever get back my courage as a climber? Did I even have any?

“The grave mistake you made, in all your innocence, was to suppress your anxiety with pills,” she says, “because that stops you learning any other ways to stop your anxiety from freezing you to a rock face.” She says I would’ve been much better off working with cognitive-behavioral techniques, a way of retraining one’s thoughts. This leads to another, bleaker realization: I’ve learned no life-coping skills during the pill years. People on benzos lock into the anxiety trap as tightly as an acorn in fresh cement. Ashton does, however, extend a bough of hope. Because of the benzos’ muscle-relaxing and cognitive-fogging properties, I was likely climbing nowhere near my potential. She suggests I process the murk with a sports psychologist.

I hope she’s right—that the person who climbed for years without benzos still remembers the rules. Fortunately, as mental vigor returns, I realize that I’ve had it all along. No, I don’t stick my neck out anymore, but I’m also older now, and less keen to die on some goddamned rock.

Four and a half years after my last benzo, and three plus change after my last psych med, I am not “better.” This story was not text-messaged from Longs Peak after I climbed an eight-pitch 5.12 up the Diamond. No. I’m slumped over my computer, too tired, my fingers bloated and clumsy. On bad nights, I’ll lie in bed and stare upward, waiting for dawn. At times, everything scares me. I feel an all-pervasive guilt about what I’ve put my friends and family through. I know I was a shit, that my sickness and bad decisions stained other lives.

But I am healing. I progressed from walking to weight lifting to gym climbing to sport climbing to some trad climbing again. And when I climb, that takes the symptoms away. The rictus of my face is unfreezing. A wonderful woman—my wife, Kristin—found me and Clyde. I held a full-time job and worked crazy hours, making a magazine. I’m even well enough to have, prosaically, blown a knee at the climbing gym. Some days I laugh. Some days I feel the truth of a warm ray of sun. I take no psychiatric meds, and the strongest thing coursing through my system is a single Mike’s Hard limeade each night. Still, I may not climb again the way I used to—I have lingering difficulties with breathing. And benzo survivors talk of having extremely sensitive nervous systems in the aftermath, a reality incompatible with high-end climbing. But I chose this. I put the pills in my mouth those thousands of times.

You’ve read this far and can now stand in disapprobation: Here’s a guy with a certain talent who pissed it away. Pathetic, no self-control, a real American wastrel. And you wouldn’t be wrong. But here’s another secret. If you’re an outdoor athlete and you’re good at it, you’re probably like I once was: a selfish, self-involved son of a bitch. It’s always more, more, more and me, me, me, and I was no different. I wanted to be the best. I wanted to do the hardest sport routes, to be the boldest on high, killer walls.

Why? Why not? I was addicted to climbing, and then to starvation, and when that wasn’t enough, I became addicted to drugs.

Maybe you see some of my method in your own madness. And perhaps your obsessions are “healthy”: wheatgrass, long runs, body sculpting, rock climbing. That’s great. But I tell you now, absent your passions you will feel the sharp scrape of withdrawal—just like any fixless junkie bug-eyed in a January alley. Reality can be reduced, at its sparest, to chemical reactions, our body craving the release of GABA, oxytocins, endorphins, serotonin, dopamine. It doesn’t care about their provenance. It just doesn’t. Cut off the source—any source—and you will pay.