THE WATER IS SO COLD that icebergs are floating in the middle. It's June in Wyoming, at 11,000 feet, and Lookout Lake is only half melted. The snow is still five feet deep along the shore, and chunks have calved into the water.

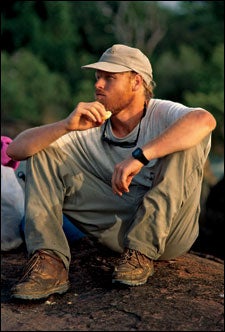

Mark Jenkins

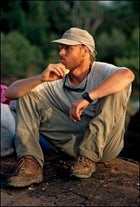

Jenkins looks back, July 2006

Jenkins looks back, July 2006Mike Moe

Mike Moe on the Niger River, Guinea, West Africa, 1991.

Mike Moe on the Niger River, Guinea, West Africa, 1991.╠ř

Mike Moe and I have hiked in to climb the Diamond, a 600-foot quartzite face in the Medicine Bow Mountains. People rarely climb here it's too high, too harsh, too dangerous. There are often snow squalls, rockfalls, route-finding debacles. Mike and I have been climbing the Diamond for 20 years; it's where we train for epics. This summer, 1995, we're going on separate expeditions to Canada: Mike to attempt a ski-and-bike traverse of Baffin Island; me to try a new route on Mount Waddington. This is our last chance to climb together.

Scrambling through the jagged terrain down to Lookout Lake, I feel nimble and at ease. We've done this so many times before, it's as though I'm sliding back through time.

At the water's edge, Mike leaps out onto a flat rock and begins to strip. He stuffs his socks into his boots and plugs them, along with his shirt and trousers, inside his backpack. Then he stands there naked, stroking his short red beard, contemplating the still, black water.

The surface of the lake is a mirror, perfectly reflecting Medicine Bow Peak and its series of stone faces. Here, at the bottom of the mountain, we are still in night's shadow, but dawn is beginning to gild the summit. Long, pink clouds, like giant rainbow trout, suddenly appear in the water. Except everything's upside down, a surreal reflection as if we're looking at the other side of life.

“Last one to the other side …” Mike says, and dives into the lake.

It was the fall of 1991, on the Niger River. Diving in from the vine bridge, Mike was immediately swept out of sight. The huge brown river just took him. It had been pouring buckets in Guinea for months and the Niger was swollen fat as a snake that's swallowed a goat, and we couldn't tell how many trees had been pulled into the water that might trap us in our kayaks, so Mike said he'd swim the river to find out. Use his body as a proxy for us and our boats. “It's the only way to test it,” he'd insisted. His wife was pregnant and my wife was pregnant and Mike and I were in Africa hoping to pull off one last big expedition before life changed for good.

Mike's done this before, but it still stuns me. The water is so cold it would instantly paralyze anyone but him. Will alone keeps him warm.

I grab his pack and begin hopping boulder to boulder through the snowfield. This is our ritual. I'll hike around the lake, he'll swim across it. We'll meet on the far side, just north of the Diamond.

It's getting light now and the air is a cool violet. I can see Mike chopping through icy water, his feet fluttering. Unlike me, he is utterly unafraid of water. It is his natural element. In high school here in Wyoming he was a state-champion swimmer.

I meet him on the far shore. When he comes out of the water, he's so frozen his skin is a waxy, translucent blue and his movements are jerky. His jaw is clenched and he can't speak, but he's grinning. He fumbles putting his clothes back on; I have to tie his boot laces for him because his fingers are wooden. Heaving on our packs, we continue up through the talus, across a hard tongue of snow.

MIKE IS A WIT, peculiarly quick-minded. He has an ever-changing repertoire of voices, a dozen nicknames for me. We rarely get the chance to go into the mountains together anymore, so when we do, we gleefully revert to our younger selves.

At the base of the Diamond, Mike stacks the rope and, finally able to talk, says, “I suppose you think you're leading.”

We both want to lead it has been this way since the beginning but, eager beaver that I am, I already have my rock shoes on. I point to them.

“I see, Rhubarb the Black's got 'iz scuppers on already,” says Mike in his pirate's brogue. “Then the sharp end be yours.”

Mike and I gravitated to each other as teenagers. We both lived on the edge of Laramie, the boundless prairie our backyard. We were predetermined to be wild and became perfectly matched partners in misadventure. Climbing came naturally to us, and we scaled everything in sight. University buildings, boulders, smokestacks, mountain walls our adolescent enthusiasm and daring far exceeding our ability. Soon enough even wide-open Wyoming started feeling small. We lied about our ages, got jobs on the railroad, lived in a tent behind the Virginian Hotel in Medicine Bow, banked the cash, then left high school to spend half a year hitchhiking through Europe, Africa, and Russia, climbing and chasing girls. We got arrested in Tunisia, Luxembourg, and Leningrad. We got robbed. We slept in the dirt.

Through college at the University of Wyoming, Mike and I double-dated, debated Nietzsche, and stood back to back defending atheism, dismembering our Christian attackers with rapier tongues. We ice-climbed and skied the backcountry and went on expeditions. Close calls were commonplace, and we thought nothing of them. We pushed each other but willingly stood in for the other whenever one of us was weak or scared or lost. We were outdoor brothers-in-arms. We would die for each other without flinching and almost did a dozen times.

“You're on,” Mike announces, and I start up a dihedral between the wall and a delicate pillar. The pillar ten feet wide, ten feet thick, and 200 feet tall leans precariously against the Diamond. We have used this route to gain the upper face multiple times, but it always feels dicey. We console ourselves with the fact that the pillar has stood here for thousands of years.

Today the crack is running with water and dangerously slippery. Halfway up I mention this fact.

“Is that whining I hear?” cries Mike in his Monty Python voice. “Courtesy slack coming your way.”

We were 16 and just learning how to climb and we made a pact that whining was prohibited. No matter how freaked you were, you had to keep your mouth shut. To enforce this rule Mike came up with a penalty called “courtesy slack”: The belayer fed out extra rope so you'd take a longer fall whenever even a whimper was heard. Over the years, this bred a black, Brit-like humor in Mike. The more desperate the situation, the more he made fun of it: “It's absolutely grand no handholds whatsoever” or “If the ice were only a wee bit thinner and more rotten I could actually enjoy myself.” We were ripe with hubris. As far as we could tell we were indestructible.

At the top of the pillar I move onto the wall and set up a belay, and Mike begins climbing. I notice that he moves more slowly than he used to, but then he doesn't climb so much anymore. He has other passions now.

After college, we both did big expeditions I went to Shishapangma and Everest; Mike walked the Continental Divide with his younger brother, Dan, then two years later mountain-biked it but our priorities were diverging. The year I went to Everest, 1986, Mike took an internship in Washington, D.C., working for the hunger-relief organization Bread for the World. In 1987, we both went to Africa. With my girlfriend, Sue Ibarra, I climbed Mount Kilimanjaro and Mount Kenya and traveled far and wide writing adventure stories. Mike went to Swaziland to work for CARE, teaching poor Swazis how to get small-business loans. He helped start a daycare center. His girlfriend, Diana Kocornik, was teaching in Swaziland for the Mennonite Central Committee. Mike started going to church.

We all moved back to Wyoming in 1990, bought houses, and started families. When I got married, Mike was my best man. At his wedding, I was a groomsman Dan was his best man. My daughter Addi and his son Justin were both born in January 1992; my daughter Teal and his twins, Carlie and Kevin, were born one month apart two years later. I kept writing stories; Mike took a job as the director of Wyoming Parent, a nonprofit family-advocate organization.

Halfway up the leaning pillar, he yells up to me, “Wish it were wetter in here!”

MIKE PULLS HIMSELF UP onto the top of the pillar and steps over to the belay.

“Mike, what if the pillar suddenly collapsed?” I ask.

“Won't,” he says. “It's been here forever.”

“But what if it did?”

“Buck, you'd catch me.”

Mike is the most optimistic person I know. He is sanguine, imperturbable.

“What if you lost your ice ax?” Mike asked one day in 1979. “Could you still climb the couloir?” We were training for McKinley by climbing the snowy chutes on either side of the Diamond. So we tried it without our axes, scraping little holds in the snow with our woolen mittens. What if you lost your ice ax and crampons? I asked. Could you still get up the couloir? We kicked tiny steps with our heavy leather boots and gouged mitten holes and climbed it. But what if you were descending? We practiced glissading with nothing to stop the death slide but a sharp rock in our hands.

Thus began our private game of what-if. What-if was meant to make us more resourceful, more capable of surviving desperate situations. And it did for a time.

We swap leads and Mike moves out onto a sheet of gray rock split by a pencil-thin crack.

“But, Mike, what if I couldn't and you were killed? Was it worth it?” I'm baiting him and he knows it.

“Yup. Right up until the moment I die … then it's completely not worth it.”

“That's not an answer and you know it.”

The crack has closed off and Mike is holding on by his fingertips. He uses this predicament not to respond.

Our game of what-if was good fun for more than a decade, but it changed after we had kids. Before, we always assumed we'd come home. That was the principle of what-if. What if this or that happened how would you get yourself out of the fix? But after kids, we both began to wonder what if … we didn't? What if we were killed? By a grizzly, by a river, by a collapsing pillar of stone. It's a natural thing to ask once you start thinking about someone besides yourself. We may be leaving on expeditions to Canada soon, but we are dads now, not Huck and Tom. Justin and Addi are three years old; Teal and Carlie and Kevin will turn one this summer. Our game of what-if has evolved into the fundamental conundrum of our lives: Is it morally possible to be a serious adventurer and a father?

For my part, I hide behind the hackneyed and sophistic excuse that it's who I am. That if I were to quit adventuring, I wouldn't be Mark Jenkins which I know is bullshit. People change all the time and don't lose their identity. They often become someone better. I just don't have the willpower.

Mike does. He's been trying to reform himself for years. He's weaning himself off adventure like a heavy drinker weans himself off Scotch. Slowly, with frequent relapses. He has promised Diana and himself he will do only one big trip every two years, but I think this expedition to Baffin will be his last. Inside, I know Mike believes serious adventure, expeditioning, is incompatible with being a father you are imperiling not simply your own life but the lives of your children, which is immoral. So he will have to give it up.

To calm his existential qualms, Mike has taken to putting more and more effort into planning the logistics of an expedition. This upcoming trip to Canada is a case in point. He's spent weeks testing gear, studying maps, developing contingencies. He told me he thinks he can bring the risk down to something acceptable. I told him he's in denial. Risk is integral to adventure. A freak accident, an unanticipatable rockslide, an avalanche. No risk, no adventure. He knows this, but he's torn between being the man he is and the man he believes he should be.

I FEEL A TUG on the rope and look up. Mike is far above his last piece of protection, and the crack has vanished. There are no handholds and nothing to stand on. Most climbers would back down.

“Watch me!” Mike yells, and dives for a thin ledge.

A letter arrived for me from Swaziland. It was 1989 and I was in Novosibirsk, crossing Siberia by bicycle. Mike wrote, “Dear Dostoyevsky the Big Legs expect you have saddle sores the size of rubles and lungs like a hippo but the KGB has no doubt caught you by now so I'll soon be mounting a daring rescue …” He went on for several paragraphs in his clumsy handwriting and terrible spelling, and between the lines I knew he was worried about me and that he was really saying he would do anything for me, march to the ends of the earth if I needed him. I missed him so much I reread the letter over and over, asking myself why I never told him how much he meant to me, why I never just told him I loved him.

Mike barely catches the lip of rock.

He belays me up and I lead the final pitch. We're 800 feet above Lookout Lake, but the climbing is relaxing and fun. Mike got the sketchy pitch, the bastard. I realize now that that's why he didn't argue for the first lead.

I reach the summit, lean against a warm slab of rock, bring Mike up, and we sit there side by side, staring out across Wyoming.”Mike, you remember Lhasa?”

He grins, but I can tell it's really a grimace.

We went to Tibet in 1993 to climb an unknown peak, and after two days in Lhasa Mike got pulmonary edema, just like he did when we were on McKinley, except there was no way to go down and his lungs filled up with fluid, and we went to the hospital, but they could only give him a Chinese army balloon of oxygen that he sucked on while we waited for the plane. His lungs were gurgling so badly he couldn't lie down, so he had to sit up all night, but even then he was still drowning from the inside. His face was bloated and gray, and if the plane didn't come in the morning he would die, but he was the funniest he'd ever been. He kept making me laugh, and I was so scared I was sick to my stomach, and when I heard the sound of the plane I began to weep.

Atop the Diamond, feet dangling in space, we are on the roof of our world. We eat the lunches our wives have packed for us and silently observe the landscape that made us: snow and ice and rock and sky. We sit there together for a long time, feeling as close as we ever have.

After a while we coil the rope and pack up the gear and begin discussing our upcoming expeditions. I'm going to Waddington with my friend John Harlin. It took a lot of persuading. His father died climbing the Eiger, and John has spent much of his adult life struggling with what that means. In his early twenties, John had a partner who died while they were descending from British Columbia's Mount Robson. After that, he promised his wife, Adele, and his mother that he would give up alpinism. Going to Waddington with me means he's breaking his promise.

Mike will attempt to ski and bike across the Barnes Ice Cap on Baffin Island with his brother, Dan, and two other good friends of ours, Brad Humphrey and Sharon Kava. I have tried to convince Sharon not to go I worry that she doesn't have the experience for an Arctic trip but Mike's enthusiasm is magnetic. It is something we disagree on. Mike believes that self-confidence and sangfroid both of which he has an abundance of are more valuable than technical ability. I don't.

I ask him what he fears most.

“Same as ever, bro.”

Years ago, Mike confided that his deepest fear was that something would happen to Dan while they were on a trip together. Dan, quiet and happy, the kid who fainted during sex-ed films in junior high, a man who has never said a bad word about anyone, has always looked up to Mike. Mike is the natural-born leader, Dan the disciple.

“I couldn't bear it,” Mike whispers.

TO DESCEND, WE WALK along the edge of the Diamond, passing right by where the plaque will be, but of course it's not there yet.

We mounted the plaque in the summer of 1996. Tim Banks and Keith Spenser and I Mike's closest friends climbed the Diamond at midnight in honor of Mike's motto, “Any real adventure begins and ends in the dark.” I led and Keith carried the engraved metal plaque, heavy as a headstone, in his pack, while Tim hiked around the back side to the summit. Halfway up, at about 3 a.m., Keith and I were shocked by little orange explosions all around us. Keith thought someone was using a night scope to shoot at us, and this seemed insane but the cracking was all around us, and then we smelled it and realized they were firecrackers. Tim was throwing bottle rockets down at us, hooting with laughter. We finished bolting the plaque to the summit block right as the sun came up.

On the hike down from the Diamond, Mike is talking about changing the world, as usual. He's been reading the research. Most kids with problems come from single-parent families. As director of Wyoming Parent, he plans to change this. He's got some ideas, but he needs state funding. He knows he can get it. He believes in legislation. He believes in laws that encourage citizens and companies to act in the best interest of the community. He believes in the basic goodness of people.

I'm listening, but I don't have Mike's faith. I used to, but I've spent too much time in screwed-up countries. I've spent too much time in places where evil things happen purely because of evil people.

In 1998 I awoke in a black, hot, locked room in northern Burma and realized I'd been dreaming about Mike every night for weeks. I desperately needed his companionship and judgment because things were getting perilous and if he'd been with me we would have balanced each other and I wouldn't have gone off the rails, or better yet I wouldn't have even come to Burma.

We've dropped down the back of the Diamond and swung around to Lake Marie and we're sloshing back through the snow to the car.

“What do you say we take Justin and Addi up here this winter?” Mike says. “Build a snow cave, teach them how to wipe with snow, howl with the wind.”

I tell Mike I'm in, of course.

IT WAS LATE AUGUST 1995 and Diana and the kids were over at our house for a backyard barbecue and we were all eagerly speculating about when Mike and Dan and Sharon and Brad would be home because it would be anytime now. Later that evening Diana called and her voice was so strange I didn't recognize it. She asked us to come over to her house, and when I walked in the door Perry and Greta, Mike and Dan's parents, were sitting stone still on the couch, and I knew immediately and my legs failed me and I dropped to my knees.

The telephone rang. It was the Royal Canadian Mounted Police out of Clyde River, Northwest Territories. Diana asked me to speak to them. I couldn't speak, so I just listened.

The team had successfully crossed Baffin Island, the expedition was over, and they were on their way home. They were coming back across Baffin Bay in a small aluminum motorboat with an Inuit guide named Jushua. They saw a pod of bowhead whales among the icebergs, and then the whales disappeared beneath the black water. Then one breached right under their boat and flipped it over. They were two miles from shore and couldn't right the craft because of the plywood steering shed. Jushua was wearing a marine survival suit, but the team had only life jackets.

On the way home from the Diamond, Mike drives. I shove in an old cassette tape I find on the passenger seat. Turns out to be Abbey Road. We know every song by heart. “Come Together,” “Here Comes the Sun,” “Golden Slumbers,” “The End.” We sing along like we have on so many road trips. I take bass and Mike sings tenor, slipping into falsetto just to make me laugh. We think we sound terrific. We sing at the top of our lungs. “And in the end, the love you take is equal to the love you make.”

Jushua was found alive, washed ashore after 18 hours in the sea. He said they held hands across the hull of the boat for as long as they could, but the water was so cold. Mike was encouraging them all and cracking jokes and reassuring them that the mighty Mounties would be sending out a search flight any minute and to just hold on, just hold on. After a while Mike was the only one who could still talk.

First Sharon slipped away, face down in the water, then Brad. Dan and Mike held on to each other, hands clasped over the hull, for six hours. Then Dan began to slip away and Mike tried to grab him, tried to hold on to his brother, but he couldn't. Mike clung to the upturned boat for two more hours, talking to himself, going mad, before floating away into the Arctic. He was 37.

When the tape ends Mike and I stop singing and are quiet for a spell. Just driving across the high plains, antelope in the distance, wind combing the tall brown grass.

Then it was October that same year and snowing and we were below the Diamond, and I was trembling holding Justin's tiny hand as he threw the ashes. Perry would never accept the death of his sons and died of heartbreak three years later. I'd see Greta alone in the park and we'd just hold hands and cry.

Years later, none of us were the same or ever could be, and the shock and despair now blessedly came only in the middle of the night. And on one of those nights in the dead of winter the giant pillar leaning against the Diamond collapsed and shattered into a thousand pieces, but the plaque we'd mounted on the summit in Mike and Dan and Brad and Sharon's memories is still there.

Eleven years after they froze to death in the Arctic Ocean, I called Diana to tell her I was writing this story. She said Justin and Carlie and Kevin would have been such different people, and we both broke down on the phone. Then she said, “But, Mark, there are so many ways to lose your life besides dying.”

As we glide into Laramie we're talking about our kids. Mike and I have big plans. As soon as they're a little older we'll take them climbing at Devils Tower, like we did together when we were young. We'll take them cross-country skiing in Yellowstone so they can sit in the hot pools like we did. We'll teach them to climb Fear and Loathing, a face route that is all about balance, about deftly moving on invisible edges, never thinking about falling, and believing with all your heart that you can stand on air.

After seven years, this will be the last Hard Way column. It has been an incomparable╠řjourney, but it's time for me to╠řembark on other writing adventures. I must thank Hal Espen, ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═°'s editor from 1999 to 2006, for hiring me and providing masterly guidance. Katie Arnold, my editor, has gently and wisely tempered every story and suffered╠řmy outrageous behavior with equipoise. Unrepayable thanks go to my wife, Sue, and my two daughters, Addi and Teal, for willingly allowing me to leave home over and over. Their love sustains me. And, finally, I'm grateful to you, the reader the reason I write.