Is adventure dead? This somewhat depressing question is one we contend with at ���ϳԹ��� all the time. After all, many of world’s great adventure prizes, including the summit of all fourteen 8,000-meter peaks and the North and South Poles, were snagged more than a half-century ago. Today’s firsts, meanwhile, are typically defined by an almost comical list of qualifiers: First blind one-armed climber to stand atop Everest. Fastest human-powered Antarctic crossing. In June. During an odd-numbered year. One can look at this increasingly parsed and trodden landscape and conclude that, yes, sadly, adventure is dead. But you’d have to willfully ignore the 60-plus years of astounding climbing evolution continuing to take place on the granite monoliths of Yosemite Valley.

This month, as part of our continuing celebration of the National Park Service centennial, we’re taking a special look at the most pivotal climbing moments in Yosemite’s storied history. To look at this list is to be reminded that the limits of what is humanly possible when flesh and sticky rubber take on a mountain of vertical granite has been radically redefined by four distinct generations of rock monkeys. In 1958, when El Capitan was still widely considered unclimbable, Warren Harding notched the first ascent after 18 grueling months of hammering in pitons. In 2012, Alex Honnold and Hans Florine tackled the same route in less than three hours. Yes, the latter feat includes a qualifier: fastest. Yet the record is no less relevant in today’s sport than Harding’s first ascent was 60 years ago.

To capture the essence of all these feats, we’ve assembled some of climbing’s most celebrated athletes and voices, including longtime ���ϳԹ��� contributor David Roberts, legendary climber John Long, groundbreaking soloist Peter Croft, and the editors of Alpinist, Rock and Ice, and the American Alpine Club. As I first combed through their odes, following the thread from Harding to Honnold, I was reminded of something another of our contributors, Greg Child, wrote in ���ϳԹ��� in 2000 in an essay heralding the sport’s Yankee pioneers: “Not long ago, the American climbing landscape and our collective climbing psyche were blank canvases awaiting artists.” That canvas is no longer blank, but Yosemite’s granite continues to be the lodestone that draws the sport’s most inspiring artists. And the radical progression shows no sign of abating. In 2015, Tommy Caldwell and Kevin Jorgeson completed the first free climb of El Cap’s Dawn Wall in 19 days. Last summer, Adam Ondra hinted at his desire to climb it in less than one. If adventure is simply an act of daring enterprise, then each season in Yosemite is proof that it is most assuredly not dead. —Chris Keyes

Contents

- 1800s: Cathedral Peak and Half Dome

- 1930s & 1940s: Valley Pioneers

- 1950s & 1960s: Half Dome and El Cap

- 1970s: The Stonemasters

- 1980s & 1990s: New Heights and Broken Records

- 2000–Present: Honnold, Caldwell, and Jorgeson

1800s: Cathedral Peak and Half Dome

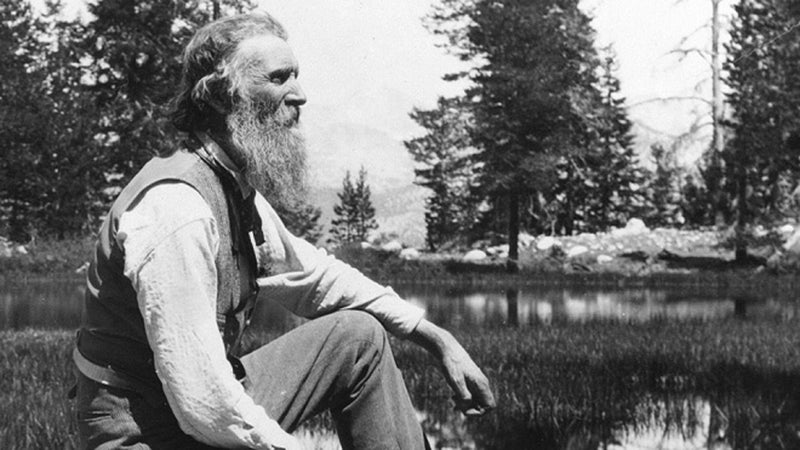

1869: John Muir Makes First Ascent of Cathedral Peak

Yosemite climbing got off to a rollicking start 20 years after the Gold Rush. John Muir was not yet the renowned nature mystic he’d become. He was a refugee of the Industrial Revolution back east who had been blinded for months in a work accident and had a case of wanderlust. He walked from Indiana to Florida, then shipped out to the Amazon, only to hear rumors of Yosemite and end up in California. Muir picked up work as a sheepherder, which, by September 1869, landed him in the deep grass of Tuolumne Meadows, staring up at Cathedral Peak.

The striking peak was cliffy most of the way around but on the west side relented to steep slabs. Up Muir went, balancing on the balls of his feet, the leather soles of his boots gripping just enough to keep from skittering back down hundreds of feet. Above rose the spiry summit, its gleaming granite smooth and vertical for 40 feet up every side Muir could reach. He would had to have clambered through a notch onto a ledge that sloped away toward a much more serious drop down the south face. The summit would have been tantalizingly close, but there would have been a death fall beneath him. This is where modern climbers in sticky-rubber shoes cinch on a nylon rope, but of course neither would exist for a good 80 years. All alone and gulping down his unease at the drop below, Muir would have jammed his feet into the gleaming granite’s only flaw, a vertical crack, which by today’s standards is rated 5.4. He would have then pulled onto the summit block, no bigger than a kitchen table.

The view was magnificent: peaks of the national park Muir would later be instrumental in creating spread to the horizon. His flock of sheep grazed contentedly in the meadow below. It was Muir’s first summer in the Sierra, which would become the subject of one of his best-loved books, My First Summer in the Sierra. He wrote grippingly of later climbing adventures but curiously said next to nothing about his Cathedral climb. Instead, awed by the mountains that would captivate him the rest of his life, what he said instead in his 1911 book, , was, “This I may say is the first time I have been at church in California.” —Doug Robinson

1875: First Ascent of Half Dome

By the latter half of the 19th century, word of the jaw-dropping Yosemite Valley was spreading around the country, and people would ride horseback for days to have a look. Big James Hutchings owned the central hotel in the meadow right across from Yosemite Falls, and John Muir had settled in the Valley, living in a loft above Hutchings’ sawmill. In his 1869 book, , Josiah Whitney, California’s official state geologist, had written off Half Dome as “perfectly inaccessible, being probably the only one of all the prominent points about Yosemite which has never been and will never be trodden by human foot.”

Whitney didn’t reckon someone like an ambitious Valley entrepreneur named George Anderson would come along.

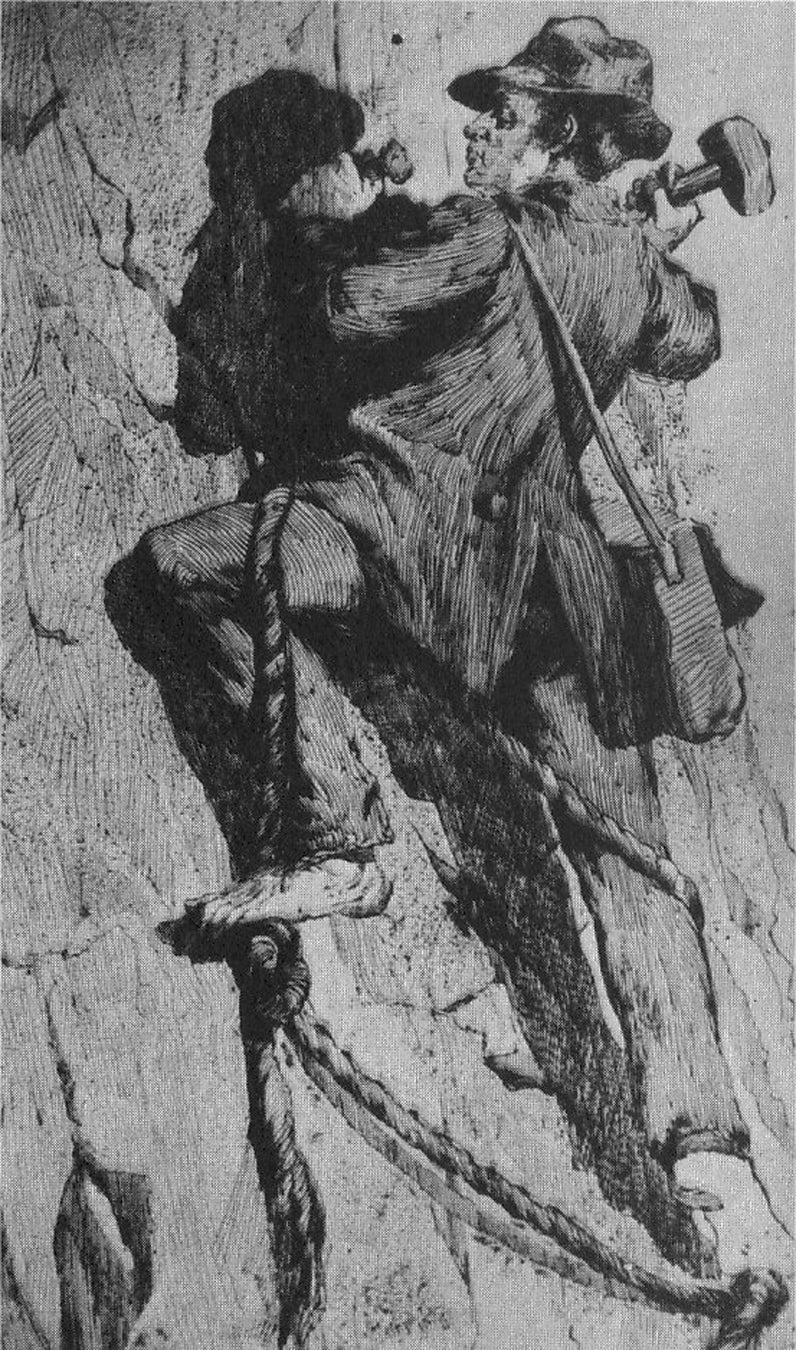

In 1875, Anderson had recently finished toiling as a laborer, busting rocks to build the first stagecoach road into Yosemite. He dreamed of perching a hotel way up on the shoulder of the dome, and guiding tourists to the summit. But his leather-soled boots were too slippery to make it up the steep, 400-foot granite slab on its eastern flank. He tried going in socks, to no avail. He smeared pine pitch onto moccasins, but that didn’t work either.

Then Anderson had an idea. He turned to his road-building tools: a star drill and heavy single jackhammer. Affixing himself to a rope, he drilled a small hole six inches deep in the wall, then pounded in an eyebolt, curled his bare toes over the end, stood up carefully in balance, and began hammering away at the next hole. It was a slow way up and a long way back down at the end of the day.

Anderson’s ascent was Yosemite’s first aided siege of a big wall and the first use of bolts. Just ten days after making the summit, he guided the first group of tourists up his lines.

Anderson never did build his hotel. Today, chest-high steel cables safeguard the still nerve-wracking climb up Half Dome—on a busy summer day, 3,000 people will hike it. Near the summit, if you look carefully, you might spy a few of George Anderson’s original bolt holes—the beginnings of what is still Yosemite’s most controversial climbing technique—one of them sporting a rusted shank that dates back 140 years to the Valley’s first bolt ladder. —Doug Robinson

1930s & 1940s: Big Walls

1933: Climbers Adopt Camp 4

At dawn each morning, climbers form a line in front of the entry kiosk to Camp 4, a walk-in campground without cars, which is unique in Yosemite. Each climber is hoping to land a spot in the dirt; the lucky ones end up shoehorned among six strangers into a campsite.

The area, a former Ahwahneechee Indian campsite, has been considered hallowed ground by the local climbing community ever since the first climbing ropes arrived in the Valley in 1933. It’s the social center, where partnerships form and tales of epics on the walls are polished over cans of PBR and Old English 800. Scattered boulders are one of its draws. At dead center, on the east face of Columbia Boulder—easily the most mammoth rock in camp—rises Midnight Lightning (V8), the most famous boulder problem in the world.

While some sponsored climbers can retreat to a house near the Valley, the legions of other climbers flock to Camp 4. But they, like campers throughout Yosemite, must abide by the park’s 14-day camping limit. Circumventing that rule can run climbers afoul of park rangers, who have been known to deploy night-vision goggles to ferret out lurkers in the woods.

An event nearly 20 years ago threatened to ruin Camp 4 forever. On New Year’s Day in 1997, meltwater poured over the rim of the Valley, washing away whole campgrounds and the riverside cabins at the Yosemite Lodge. Park planners drew up an idea to squeeze in a five-story employee dorm building above the Camp 4 parking lot.

In response, climber Tom Frost filed suit against the National Park Service and rallied climbers in protest. The rangers were near panic when 600 of us showed up one day in 1999. Law enforcement on horseback surrounded a photo session beneath Midnight Lightning, and there were speeches. Yvon Chouinard—Frost’s climbing partner—stood up to address the crowd: “If John Muir were here today, would he be staying at the Ahwahnee Hotel? Hell no, he’d be in Camp 4!”

This gathering bred new respect from the rangers, and on February 21, 2003, Camp 4 was accepted into the National Registry of Historic Places. Its future secured, Camp 4 returned to its perennial role as a crucible. —Doug Robinson

1934: First Ascent of Higher Cathedral Spire

During the first decades of the early 20th century, California’s best climbers, most of whom were Sierra Club members, took to the mountains like John Muir had: scaling logical paths to the top of the Sierra’s highest peaks, carrying neither rope nor hardware. If their routes happened to traverse airy ground, they swallowed hard and made the moves—or backed off. But lacking both a rope and the wiles to use one meant the range’s most vertiginous summits lay untouched.

In 1931, Francis Farquhar, a Sierra Club board member and its future president, learned of Harvard professor Robert Underhill’s travels among the technical peaks of the Alps and invited him to tutor the club’s best climbers in European rope management. Bestor Robinson and Jules Eichorn took part in Underhill’s classes, and Eichorn and others later accompanied Underhill on forays up two technical 14ers: Thunderbolt Peak and Mount Whitney’s East Face.

Back home in the Berkeley Hills, Robinson and Eichorn, along with club member Dick Leonard, practiced and improved on those techniques. In September 1933, they launched off to climb Yosemite’s most imposing unclimbed summit: the Higher Cathedral Spire. For two hours, they hiked steep talus slopes to the spire’s 400-foot south face, where, after a daylong reconnaissance, during which they used ten-inch nails rather than proper pitons, the difficult climbing stymied the men. They returned in November with German pitons but again were rebuffed.

In April 1934, the men returned with 55 steel pitons, two ropes, a movie camera, and a retinue that included Farquhar himself. This time, by weighting the pitons to make upward progress—which become known as “direct aid”—they gained the summit at sunset, where they unfurled an American flag, and then slid down their ropes to the ground.

Higher Cathedral was an inflection point in the trajectory of Yosemite climbing: direct aid became the solution for surmounting Yosemite’s gargantuan faces. Perhaps Robinson put it best in his account in the Sierra Club Bulletin: “Looking back on the climb, we find our greatest satisfaction in having demonstrated, at least to ourselves, that by the proper application of climbing technique extremely difficult ascents can be made in safety.”—Brad Rassler

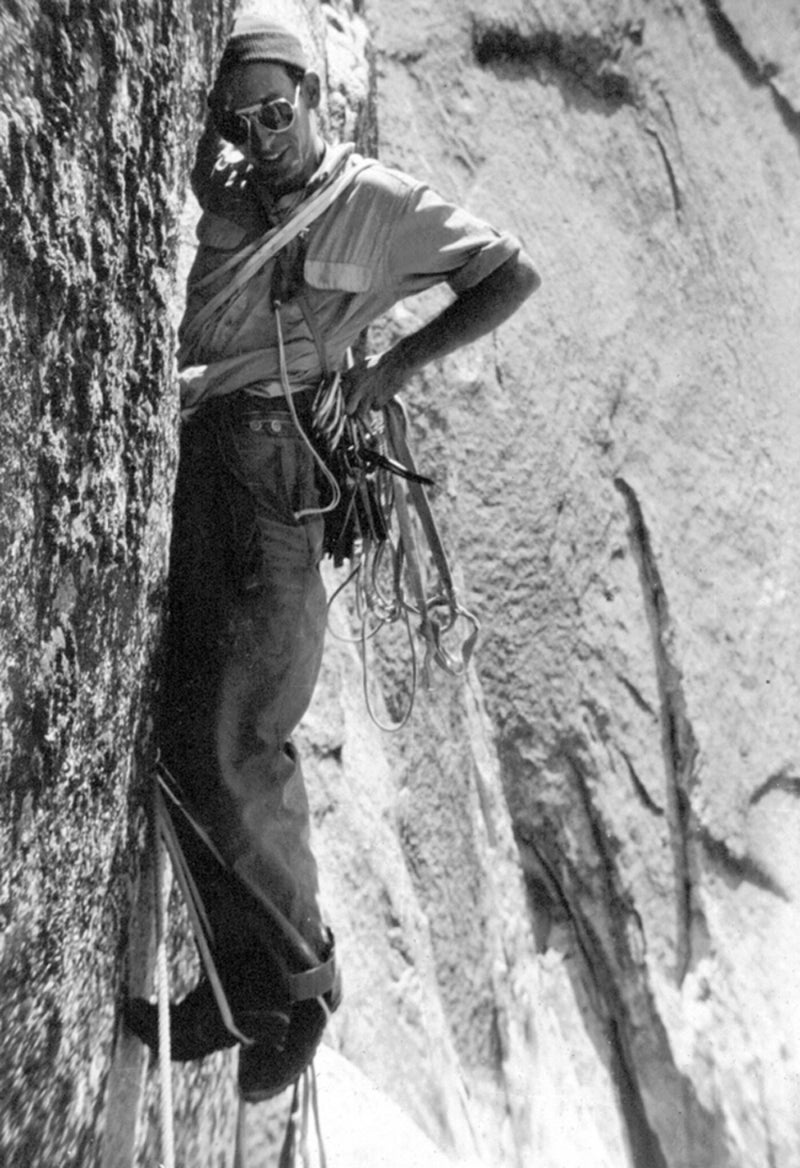

1946: John Salathé’s Pitons

In 1946, John Salathé, a Swiss immigrant, was eyeing the Lost Arrow Spire, a 200-foot granite pillar in the Yosemite Falls area that stands alone, offset from the main wall by 120 feet. The Lost Arrow was considered an ultimate prize, and as Salathé eyed a route from its base to the tip via a series of cracks and chimneys, he knew it would be the longest and most technical climb yet attempted in Yosemite.

Salathé soon learned that the rock’s many shallow cracks, which chewed up the standard soft steel pins of the day, would complicate an ascent by piton. His pitons deformed when nailed into a bottoming slot; they also got stuck in the rock, or their heads broke off from repeated hammer blows.

Salathé could have bolted his way through the rock’s difficulties, but he hated the idea of cheating his way up the climb. He solved the problem by forging a set of pitons from carbon steel containing vanadium, the same alloy used to make Ford Model A axles. The following year, Salathé and his partner, Anton “Ax” Nelson, used the new pitons for five consecutive days and four nights to make the first ascent of the Lost Arrow Chimney. Word got out about Salathé’s climb and his amazing pitons, but he made just a handful for himself and a few friends.

By the time I arrived in Yosemite Valley in 1957, Salathé and his pitons were gone. So I made a similar set for myself, and then for friends, and then for friends of friends, because everyone realized that the chrome-alloy steel piton was the key that unlocked the door to Yosemite’s big walls.

Take the North America Wall on El Capitan, with its difficult aid climbing at the bottom. Most of those first four pitches go at A3, and we couldn’t have climbed them without hard steel pitons. I made 50 in various sizes, which we leapfrogged to the top.

Business school professors and venture capitalists are fond of the term “disruptive innovation” to describe stuff that fundamentally changes how the game is played. Salathé’s pitons were certainly game changers. They advanced the state of big-wall art and ushered in Yosemite’s golden age.—Yvon Chouinard, as told to Brad Rassler

1947: First Ascent of Lost Arrow Chimney

The slender Lost Arrow Spire, to the right of Upper Yosemite Falls, was first summited, in 1946, by a group of Californians. The team threw a weighted line over the tip from the Valley rim, 125 feet away. Two men then rappelled into the notch between the spire and the rim and ascended ropes to the summit. “Spectacular and effective though [it] was, this maneuver required very little real climbing,” admitted 29-year-old Anton “Ax” Nelson, one of the climbers.

The next year, looking to climb Lost Arrow via a more sporting route, Nelson joined forces with John Salathé, a 48-year-old Swiss immigrant who had already tried twice to climb the spire from the notch. Although they were born a generation apart, both men were skilled tradesman, teetotalers, and happy to pack only dried fruit, nuts, and gummy bears, plus about two pints of water per day, for their multiday climb from the foot of the spire. They were armed with 18 of the revolutionary pitons that Salathé, a metalworker, had forged from a Model A car axle—these could be repeatedly driven into tiny cracks without buckling—and a curved skyhook for hanging onto ledges.

All through the summer, rival teams traded attempts on Lost Arrow Chimney, the 1,200-foot gash forming the spire’s left side. Over Labor Day weekend, Salathé and Nelson passed the previous high point. Steeper rock then slowed them to a crawl—they managed a total of only 400 feet during days three and four of the climb, enduring long, windy bivouacs sitting on bare rock with no tent or sleeping bags. “Food, sleep, and water can be dispensed with to a degree not appreciated until one is in a position where little can be had,” Nelson wrote later. On the morning of the fifth day, they finally stood on top. The Lost Arrow Chimney, made possible by new gear and a bold style, was by far the hardest wall climbed yet in North America, paving the way for much bigger faces on Half Dome and El Capitan.—Dougald MacDonald

1950s & 1960s: Half Dome and El Cap

1957: First Ascent of the Regular Route on Half Dome

In the annals of Yosemite history, there are two eras of big-wall climbing: before Half Dome, and big-wall climbing after Half Dome. That’s how much the first ascent of the wall’s sheer northwest face changed the trajectory of the sport. The leader of the first ascent team was not only the most gifted athlete of his era but was the first climber to become a brand for vision, ethics, and boldness, years before he launched the clothing line that would bear his imprimatur.

The northwest face’s first several hundred feet climbed like much of the rock elsewhere in the Valley. It was the topmost two-thirds that were unprecedented in scale and verticality, with an average angle over 80 degrees. Peering up at the probable route from the base, a team would be forced to connect a discontinuous series of ledges, chimneys, and flakes, and somehow navigate around or through Half Dome’s “Visor,” a fearsome overhang that loomed over the 2,000-foot face.

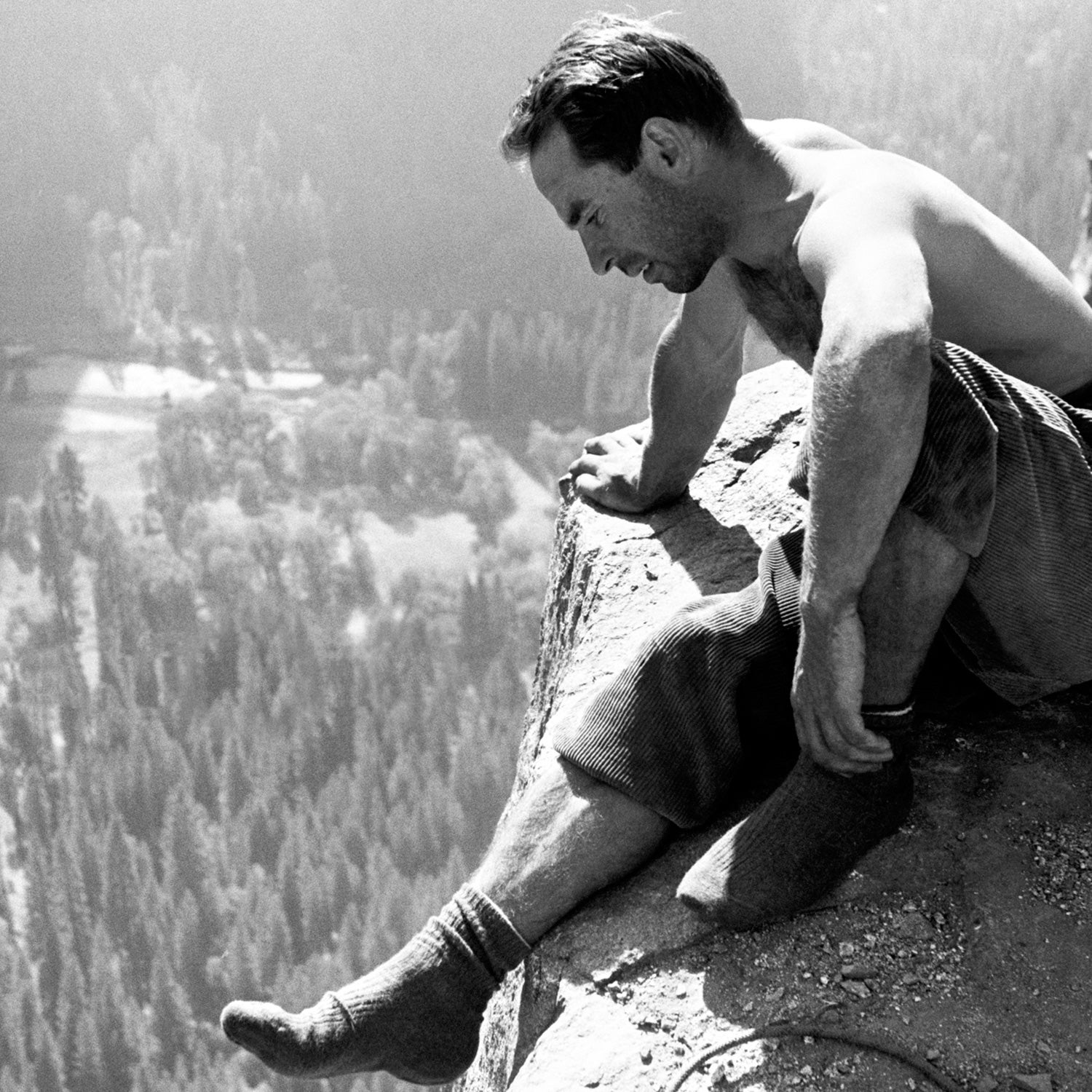

In 1955, Royal Robbins ventured onto Half Dome’s northwest aspect for the time, accompanied by a trio of seasoned climbers: Jerry Gallwas, Don Wilson, and Warren Harding. But it was so difficult—both technically and psychologically—that the team abandoned after 450 feet. “It wasn’t that the climbing was so hard,” wrote Robbins in his memoir, Fail Falling, “but rather that the vertical vastness cowed us.”

Two years later, Robbins and Gallwas tried again with Mike Sherrick, and the three clambered onto Half Dome’s broad summit, having negotiated features that have become the stuff of legend: the Robbins Traverse, the Robbins Chimney, the Zig Zags, and the improbable Thank God Ledge. When the three reached the top, the competitive Harding, who had coveted the climb, greeted them with a bag of sandwiches and a gallon of water.

“Hey, congratulations, you lucky rotten bastards,” he said, remembered Robbins in his memoir. The men packed up and began their hike out. They should have returned to the Valley as heroes for conquering Yosemite’s most iconic wall, but save for a few climbers, most people were ignorant of their venture. And thus with Half Dome—a climb in which Robbins “[began] a lifelong effort to make adventure an aesthetic standard,” according to Yosemite historian Joseph E. Taylor—Robbins threw down the gauntlet for every climber of his era, and for those yet to come.—Brad Rassler

1958: First Ascent of the Nose

The fall days were cold and short, and climbers Warren Harding, Wayne Merry, George Whitmore, and Rich Calderwood were within shouting distance of the summit on El Capitan. Only one final obstacle, a bald and overhanging headwall, separated them from success on the mightiest rock wall in the contiguous United States.

The four had been on the route for 11 days during their final push—twice as long as any American had ever spent on a rock climb. They’d met obstacles no climber had ever faced, let alone mastered: swinging wild pendulums, hammering a string of homemade pitons behind expanding flakes threatening to peel off the face, rats gnawing through their sleeping bags, and rope-hauling hundreds of pounds of food and water up a granite cliff.

At dusk, the climbers ate their last candy bars. Then Harding strapped on a headlamp and started hand-drilling bolts—the only way to overcome the headwall. In a 12-hour marathon, as Merry hung belaying from slings, Harding hammered through the night. Finally, at 6 a.m., Harding asked Merry if he could hang on for one more bolt.

“Jesus—can I hang on?” said Merry in an interview 50 years later. “I had been standing there looking up all night at this little spidery figure haloed by its headlamp, dangling under overhangs and banging away above his head—and he asks me if I can hang on!”

At last, the rope slipped into the first rays of sunlight as Harding punched home the 28th and final bolt and stumbled to the top. The first ascent of the South Buttress of El Capitan—the Nose—the most celebrated and sought-after rock climb in the world, was finally history. The date was November 12, 1958.

Not until Harding and Co. began their first sorties up the Lower Buttress had anyone even considered climbing El Cap. In the decade after their first ascent, the route came to be considered the best and most well-known climb in the world. —John Long

1961: FA, The Salathe Wall, El Capitan (Robbins, Frost, Pratt)

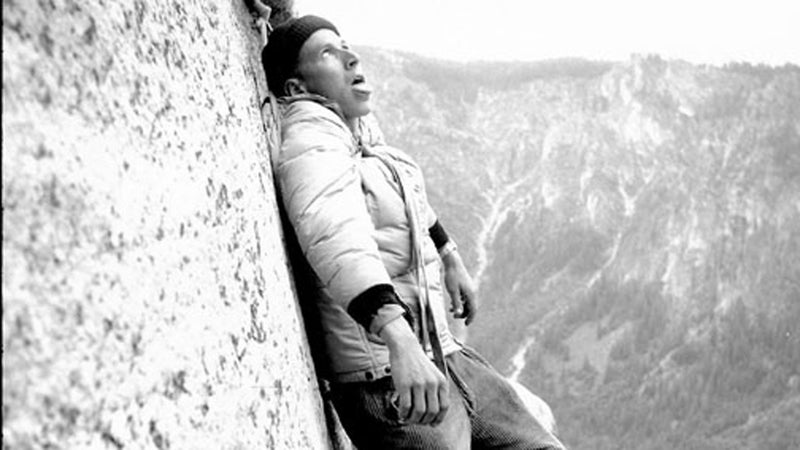

On a September day in 1961, three climbers nearly 1,000 feet up uncharted terrain on El Cap threw three of their six ropes down to the distant ground. Royal Robbins, Tom Frost, and Chuck Pratt were committed—having chucked their only means of rappel, they could only go up.

Until then, only one route had been climbed on El Cap—the Nose, three years earlier—and certainly no helicopter or other rescues occurred there. The Salathé Wall would be the second route on the monolith.

The three men encountered difficulties demanding the latest techniques. At one point on the wall, Robbins, a pendulum expert, swung wildly sideways on a rope to cross over from one crack system to another. At another point, he led a terrifying unprotected chimney called the Ear. Pratt led a hard jam crack to a glorious bivvy on a 12-square-foot platform topping the detached El Cap Spire.

Four days in, the three men were under a 15-foot roof 500 feet from the top. Frost took lead, finding hidden cracks, stretching his arms to nail pitons in place. As Robbins wrote in “I will always remember Tom leading that pitch.”

Frost surmounted the roof only to discover the now-famous headwall that overhung for 200 feet. Pratt took over, jamming anew up one of the hardest pitches of the route. For a climber, sticking ones toes to the rock in that section is to feel one’s heels hang over vast empty air. On the sixth day, having placed only 13 bolts, the men reached the top.

“No new climb the length and difficulty of El Cap’s southwest face ever had been done in one push without fixed ropes,” wrote Steve Roper and Allen Steck in their book . The climbers’ choice to minimize use of such “siege tactics” on unknown terrain upped their personal commitment, increased the amount of gear and supplies they must carry, and ultimately proved the feasibility of a new idea.

As Roper says today, that first ascent “proved that a huge wall could be climbed (mostly) without fixing ropes—a big step upward. Going into uncharted land without the umbilical cord was very bold.”—Alison Osius

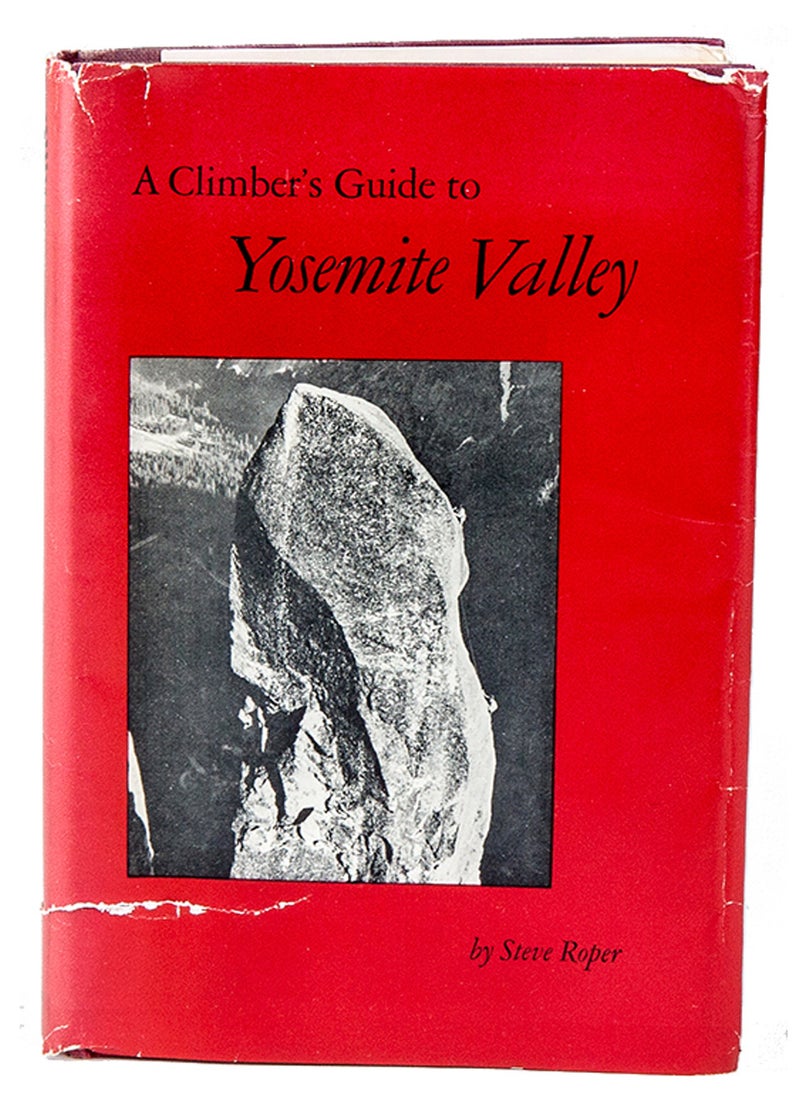

1964: The First Comprehensive Guidebook

The American Alpine Journal labeled Steve Roper as one of two “godfathers of American climbing literature,” along with Allen Steck. Nobody has written more astutely, insightfully, informatively, and, in some places, enigmatically about American climbing than Steve. Nowhere is his erudite imprint on the genre more evident than in that first Yosemite guidebook, . It was the first collection of all the Valley routes, succinctly described per pitch, and it gave any climber democratic knowledge of what was previously available only to a few Camp 4 regulars. The book is no longer used, but it set the standard for today’s guidebooks.

When I came to Yosemite in 1968, just after I’d started climbing, Roper was an icon, having completed many of the finest first ascents in the Valley. Few Yosemite climbers, novice or veteran, were without his book. It led countless climbers to and through and up and down the finest adventures (and misadventures) of their lives. It established the Yosemite Decimal System as the standard for rating American rock climbs and described the routes in well-written English rather than topo drawings. “Topos are controversial in that they tend to make climbing a bit easier on the brain,” Roper wrote in the guidebook’s second and final edition, published in 1971. “Topos assure speed records; they also lessen responsibility … Part of the adventure of climbing is removed.”

I wish I still had my copy. —Dick Dorworth

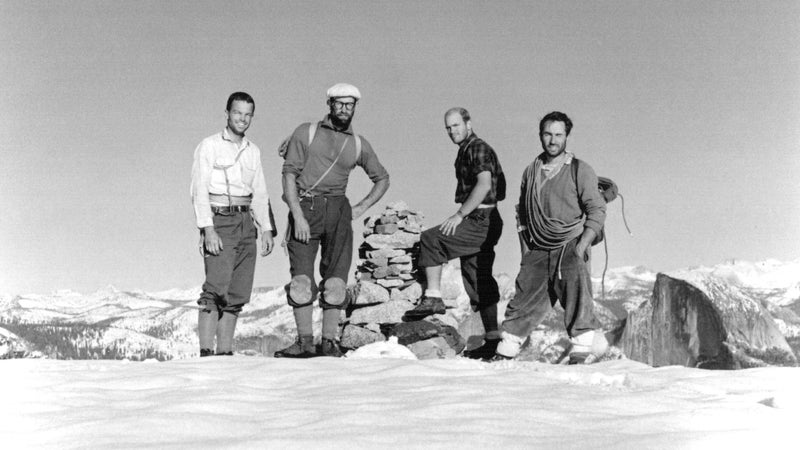

1964: The North America Wall

The current Yosemite big-wall guidebook lists more than a hundred routes on El Capitan, but in the early 1960s, there were just four. Those routes all led up the mountain’s southwest face, which, while no pushover, is less steep than the then-unclimbed southeast face. In 1963, the methodical Royal Robbins began probing this overhanging territory. His exploratory forays drew him into a moody geologic feature of black diorite that bore an uncanny resemblance to the map of North America.

At the time, Robbins was the driving force of big-wall climbing. He had repeated all the routes on El Cap and pioneered one, the Salathé Wall. His vision for the North America Wall was to make a statement about the ethics of climbing the big stone. The wall would be a departure from Warren Harding’s months-long siege that created the Nose, with its umbilical cord of fixed ropes to the ground that had become de rigueur on other routes. In the Robbins dictum of rockcraft, there would be no ropes tempting retreat to the ground; instead, there would be total commitment.

In October 1964, Robbins assembled a team with Chuck Pratt, Tom Frost, and Yvon Chouinard for his brash climb. With no certain idea of where the discontinuous crack systems would lead them, the men zigzagged through massive overhangs like the ominously named Cyclops Eye—hammering steel, dangling in aid slings, and bivouacking in crude hammocks—to climb over the top on the tenth day.

In Chris Jones’ 1976 book, , the summit photo of the triumphant foursome standing amid a dusting of snow is captioned, “For the first time in the history of the sport, Americans lead the world.” The California-style big-wall tactics refined in Yosemite would spread to mega-cliffs around the globe. —Greg Child

1970s: The Golden Era

1970/1: The Wall of the Early Morning Light (Dawn Wall), and Erasure of the Route

Warren Harding was the polar opposite of Royal Robbins. Where Robbins took climbing seriously, “Batso” Harding couldn’t give a “rat’s arse.” He carted flagons of wine up walls. His Camp Four party world of sports cars and girlfriends was infamous. His writings about climbing were irreverent. The title of Harding’s 1975 autobiography, Downward Bound, sums up his approach to climbing.

Every first ascent on El Cap has employed a certain amount of drilling, a tactic of tapping a hand drill with a hammer and bashing in a rivet or bolt to connect discontinuous cracks. But in the late 1960s, some climbers developed ethics that shunned too much bolting. Robbins preached that sermon loudly, even though he’d bashed 110 bolts into Tis-sa-ack, his 1969 route on Half Dome. Harding, on the other hand, made liberal use of his hand drill.

In November 1970, Harding and Dean Caldwell started up a sweep of rock dubbed the Wall of the Early Morning Light (later abbreviated to Dawn Wall) because it’s where the first kiss of dawn hits El Cap. They spent 27 days aid climbing and hauling 300 pounds of gear. They endured storms, and they refused rescue by the National Park Service. On top, they met a throng of media.

“Why on God’s green earth do you guys climb mountains?” asked a reporter.

“Because we’re insane, can’t be another reason,” .

Along with recognition came criticism. Robbins complained they’d beaten El Cap into submission with too many bolts—they’d drilled 300. In 1971, Robbins and Don Lauria set out to repeat and “erase” the route by snapping off the rivet heads with hammer and chisel. After deleting 50 or so bolts, however, they stopped chopping. Why? Robbins and Lauria found Harding’s route to be worthy after all, given the technical difficulty. But by then, they’d done everlasting damage to Harding’s route.

Harding and Robbins had long been rivals, but neither man quite recovered from having his climb destroyed or from being the destroyer. Harding never climbed El Cap again. Almost a half-century later, the tale still looms over the mountain like a Greek tragedy, with some murky moral about excess and ambition. But Harding may have gotten the last word on it. In his article “Reflections of a Broken-Down Climber,” published in Ascent in 1971, Harding snidely said of Robbins’ obliteration of his route, “Perhaps he is confusing climbing ethics with prostitution morality, like a 100-bolt climb (or a $100-a-night call girl) is proper, but a 300-bolt climb (or a $300-a-night call girl) is immoral.”—Greg Child

1973: First Hammerless Ascent of Half Dome

To climbers venturing up Yosemite’s crack-riven walls in the sport’s earlier decades, nothing was so reassuring as the ring of a well-driven piton. But as more climbers entered the Valley and vied for the same classic climbs, repeated hammer bashing was transforming those pristine cracks into a series of unsightly divots.

Then, in 1972, Doug Robinson’s now-famous essay, “The Whole Natural Art of Protection,” was published in the Chouinard Equipment Catalog. Robinson made the case for holstering hammers and sequestering pitons and taking up nutcraft, not only for the sake of the stone but also for honing one’s mastery of the medium. “Clean is climbing the rock without changing it; a step closer to organic climbing for the natural man,” he wrote. Robinson’s polemic was compelling, but a proof of concept was required to carry the day. As it turned out, the opportunity would fall into his lap within the year.

In 1973, Galen Rowell, a climber and auto mechanic, scored his first big break as a photojournalist when National Geographic hired him to chronicle the ascent of the Northwest Face of Half Dome. He approached Robinson and Dennis Hennek and was surprised when they demurred after Rowell suggested that they would use pitons to ascend the wall. “Here I was, sharing a dream come true with Doug and Dennis, and all they could say was, ‘Wait a minute—this article could corrupt rock climbing,’” , when I interviewed him for Climbing magazine.

No Yosemite Grade VI had ever been climbed without pitons. Rowell needed to succeed for the story to run, but he saw how a hammerless climb would enhance the article and further the cause. “So together we conjured the idea of how the story–if it were published–could be something that would advance climbing,” Rowell said. He consented to go up on Half Dome with the hammer stowed in the bottom of the haul bag, only to be used in an emergency. Robinson and Hennek agreed, but during the packing made sure to “forget” the hammer and pitons. Rowell wouldn’t learn of their trickery until after they were well up the cliff, too late to do any good. Two days later, they reached the top.

Rowell’s story, “Climbing Half Dome the Hard Way,” ran on the cover of National Geographic’s June 1974 issue, along with an exegesis on clean climbing. It proved the death knell of pitoncraft on all but the most extreme aid climbs, and the peal of steel on steel eventually faded from Yosemite. Using nuts increased risk and required better technique, but it preserved the rock. And it’s been that way ever since. —Brad Rassler

1973: First All-Female Ascent of El Capitan

In September 1973, Sibylle Hechtel lay awake in her tent in Yosemite Valley, too anxious to sleep. In the darkness beyond the trees, the monolith of El Capitan seemed overwhelmingly vast. She and Beverly Johnson hoped to make an ascent of the Triple Direct, a route that included portions of the Salathé Wall, the Muir Wall, and the Nose—realms of sheer, polished granite that Yosemite historian Steve Roper compared in his book to the “inside of a cut diamond.”

No all-female team had ever climbed El Capitan before. In a recent phone interview, Hechtel says that men had offered to “take [her] up it,” but she longed for more autonomy. She also worried they might try to pressure her to sleep with them. “We can’t retreat under any conditions,” she recalls Johnson warning her. “We’ll never live it down.”

After fixing ropes on the first four pitches, the two women committed to the ascent. Hechtel’s initial fears subsided as she became absorbed in the rituals of moving up a big wall. Under the intense autumn sunlight, she and Johnson hauled bags that weighed more than their bodies. At night, they watched the stars illuminate the seemingly endless pale stone.

Unlike modern climbers, the women had no detailed topo maps, only fragmentary verbal descriptions that didn’t include the Muir Wall. On Block Ledge, hundreds of feet in the air, they found themselves, suddenly, lost. Ahead rose disorienting expanses of gray rock with no signs of previous passage.

“Charlie!” Johnson shouted to her boyfriend, who was waiting in the meadow below. She imagined he might yell directions back. Gusts of wind blew away any words. At last, Johnson chose the most promising-looking crack, and she and Hechtel continued. On the sixth evening, as they raced an approaching storm, Johnson led one of the final pitches with their single headlamp while Hechtel fumbled behind her in the dark. They spent the rest of the night hanging from slings, waiting for dawn. In the morning, they staggered over the rim and into the enfolding clouds.

When the printed Hechtel’s story, editors removed her original title, “Walls Without Balls.” Nonetheless, the phrase became legendary—symbolic of a larger struggle for female independence in the wild and the world. Already, in the April 1974 edition of Summit, Hechtel wrote triumphantly of a “veritable explosion of women on walls.”—Katie Ives

1975: El Capitan in a Day

Jim Bridwell, Billy Westbay, and I were loafing in the Yosemite Lodge when someone dropped off a copy of Mountain Magazine featuring Reinhold Messner and Peter Habeler—in knickers and snazzy red guide sweaters—posing in front of the mighty Swiss Eigerwand the day after their ten-hour blitz ascent. The flap copy went on about the greatest speed ascent of all time. Bridwell, then the high lama of Yosemite climbing, nearly threw the magazine in the fire.

“Time for us to check—and raise,” he said.

The following Memorial Day, in 1975, at 4:30 a.m., Jim, Billy, and I started up the Nose on El Capitan to attempt the first one-day ascent. We’d each done the route once before. Bridwell had worked up the logistics on graph paper. I led the first 17 pitches, mostly free-climbing up the cracks piercing the South Buttress. I got us on top of the 60-foot-high Boot Flake by 7:15 that morning. We were smoking.

Billy took the lead, racing across funky diorite over to the Great Roof, a sweeping arch of beige granite, then bashed his way up the vertical corners to Camp Six, a small, triangular ledge only 600 feet below the summit. Jim grabbed the lead and hammered skyward as the meadow below filled with friends and onlookers honking horns and spurring us upward. The pitches whirred by so fast that I could barely clip off the belay anchors before having to chase after the leader on mechanical ascenders fastened on the rope. We crested the summit at 7:25 that evening, some 15 hours after we started.

We raced down the East Ledges descent route and, just after dark, stumbled onto the Loop Road. We hoofed around to Jim’s van, and a moonlit El Cap hovered into view, towering like a dream half-remembered. We didn’t feel like conquerors, but honored guests at a shrine. I went on to have many adventures, and have forgotten half of them, but never the brotherhood and awe I experienced climbing El Cap in a day with Jim and Billy.

Nose in a Day, or NIAD, has since been accomplished hundreds of times by teams from around the world. By no means was ours the first speed climb of a Yosemite big wall, but NIAD shattered a last psychological barrier. After that, the prevailing thought became that if you could dream it, you could do it—an orientation that has raised the Yosemite bar to heights unimaginable in 1975.—John Long

1975: First Free Ascent of Astroman

From the broken boulders at its base, the East Face of Washington Column, facing Half Dome, rises as a gorgeous hunk of orange-streaked god stone split by one of the finest crack systems a climber will ever see. Legendary hardmen Warren Harding, Glen Denny, and Chuck Pratt claimed the first ascent in 1959, back when it was called simply the East Face of Washington Column. The challenges they faced ran the gamut: fissures varying from fingernail width to bombay chimneys split the 1,200-foot wall, making it a test piece for the aid climbers of the 1960s.

Then, in 1975, the route became something else entirely. The free-climbing revolution—a shift in emphasis from completing climbs by any means necessary to more refined methods—was taking root in Yosemite Valley. No one exemplified the new guard more than John Bachar, John Long, and Ron Kauk. Everything they did was swashbucklingly cool and became iconic—including the paisley headbands and white painter’s pants they wore while climbing.

In May of that year, the three men set out to use the techniques they’d been developing on the smaller crags—like hand jamming and fingertip face climbing—and apply them to a much bigger canvas. By using their cutting edge skills to free-climb the steep East Face, they completely changed the way the climbing world looked at big cliffs. People had done 100-foot climbs with that level of difficulty, but stacking that level of difficulty on a long multipitch—with that much air below their heels—was unheard of. It instantly became the most famous free climb in the world. They named it Astroman.—Peter Croft

1978: Ron Kauk Climbs Midnight Lightning

Columbia Boulder is a 30-foot-high granite rock rising from the center of Yosemite Valley’s Camp 4, the most storied climber’s campground on earth. Since the 1940s, when climbers started regularly visiting the Valley, the young and restless have hurled themselves at the big gray hulk, though the top was rarely achieved.

Sometime in the mid-1970s, John Yablonski—tripping on LSD, as the legend goes—spotted a line of tenuous holds sweeping up the rock’s bulging east face and hallucinated a route that would later become the world’s most famous bouldering problem. Joined by Valley stalwarts Ron Kauk and John Bachar, Yablonski began serious efforts on the problem in the summer of 1978. During one session, Bachar chalked the image of a lightning bolt on the rock face by the route. Midnight Lightning, as the problem was immediately coined, derived from a posthumous album by rock guitarist Jimi Hendrix and a lightning bolt–shaped hold in the middle of the overhanging crux section. The lightning bolt is still there, rechalked by other climbers over the years.

Nearly 40 years after Kauk’s iconic first ascent, on most any summer afternoon, crash pads are stacked like cordwood below Midnight Lightning, and climbers from Switzerland to Shanghai are hurling themselves at Columbia Boulder. And just as it was in the earlier days, when climbers clawed at the easier south and west faces, the top is rarely achieved.—John Long

1980s & 1990s: New Heights and Broken Records

1981: First Ascent of Bachar-Yerian

In the summer of 1981, John Bachar, followed by his partner, Dave Yerian, launched up the crackless ocean of gold granite on the right side of Medlicott Dome in Yosemite’s Tuolumne high country. By the time Bachar stood atop the 500-foot face, he’d done more than establish a hard climb. He had created a monument to boldness.

“Watching John climb was like listening to Coltrane,” Yerian said in a 2012 issue of Rock and Ice. “Bachar was so far ahead of his time that no one could understand what he was doing.” The climbing was tricky and dangerous. Bachar climbed on sight from the ground up, occasionally drilling bolts and slinging wee knobs for protection. He placed a scant eight protection bolts in four pitches, a handful of which he sunk while hanging from a hook.

Bachar’s tactics compromised the “stance only” drilling ethic of the era, in which bolts were placed only where one could stand on the rock face. But the route was steeper than anything to date, and Bachar felt that by bending the rules—a recurring theme in climbing history—he could push the sport into a new realm. A few months before his death, in 2009, Bachar wrote in Alpinist, “The farther apart the bolts were, the more of an artistic statement I could make about the value of skill over technology.”

Today, the Bachar-Yerian is graded 5.11c, R/X. Many argue that it’s harder. Regardless, the grade does not speak much to its true nature. It’s a righteous scarefest. Supertopo’s guidebook calls it the “most famous psychological testpiece in the U.S.” Though the technical crux on pitch one is well protected, the second turns back the biggest number of would-be suitors. This includes the likes of Wolfgang Gullich, who broke a quartz crystal and sailed 60 feet while attempting the second ascent.

Bachar recalled in Alpinist, “Over and over I’d felt my whole life come down to one small move, one crystal—and within those tiny spaces and moments, I’d tried to get a measure of myself.”—Pete Takeda

1986: Bachar and Croft Climb Half Dome and El Cap in a Day

Thirty years ago, I drove down to Yosemite Valley with a secret plan to climb the two biggest landmarks in Yosemite—El Capitan and Half Dome—in one day. A smirking buddy pointed out that my résumé didn’t include either one of these giants in a day. He was right. But for the previous two or three years, I’d been linking big cliffs, alone, and the prospect, as farfetched as it sounded, felt like an achievable dream.

Dream turned to destiny when, stepping out of my car, I was greeted by none other than John Bachar, the most famous climber in the world. Without a word from me, he suggested we attempt the very same linkup I had in mind. I could practically hear the gears of the cosmos clicking into place as the planets aligned.

John and I spent the next few days climbing together to get a feel for each other, and then we took a two-day break to prepare. At the stroke of midnight, we turned on our headlamps and grabbed the first handholds on El Cap. Sneaking past climbers sleeping on ledges on the wall and, higher up, passing others who immediately deferred to royalty (John), we pulled onto the summit around 10 a.m. We paused to enjoy the moment. Feeling stronger on the summit than we’d felt at the bottom we couldn’t wait to get up on Half Dome.

By early afternoon, we were climbing Half Dome’s northwest face, blue-black thunderheads rolling in from the east. Normally, threatening weather might be reason for retreat, but it merely added voltage to our energy. When the first raindrops fell and the static electricity caused our hair to stand up, we just accelerated. It was like the forces of evil were now being used for the forces of good. When we stood on top, we looked up at a perfect double rainbow.

As we hiked off the top of Half Dome, I remember wondering to myself, “What’s next?” It didn’t feel like the end. It felt like the beginning.—Peter Croft

1988: Paul Piana and Todd Skinner Free the Salathé

When Todd Skinner and Paul Piana free-climbed El Cap’s Salathé Wall in 1988, they redefined what was possible on Yosemite’s biggest walls. Royal Robbins, who did the first ascent as a cutting-edge aid climb in 1961, called the 35-pitch route “the greatest rock climb in the world.”

Before Skinner and Piana’s free ascent, no one had climbed such mind-boggling difficulty in such an outrageous position. Seven pitches were rated 5.11, four were 5.12, and four were 5.13—unthinkable for the era.

In preparation, the pair spent 30 days over two months fixing hundreds of feet of rope, hauling humongous loads, and finally rappelling in from the top of El Cap to work the moves.

The renegade tactics broke the “rules,” raising the hackles of the Valley rank and file, breeding skepticism, outright slander, and character assassination. Some pundits doubted their free ascent even after the climb was repeated and confirmed at the grade. The free Salathé was every bit a triumph of ascent as rising above the morass.

The pair spent nine days on their final push enduring long falls, hunger, storm, and mangled hands. On the summit, a huge granite block—their primary anchor—cut loose, severing ropes, breaking Skinner’s ribs, and crushing Piana’s foot. By chance, Piana had backed up the anchor to some old pitons, saving them from a 3,000-foot plunge to the Valley floor.

What was controversial proved an evolutionary stepping-stone and, finally, the norm. Lynn Hill wrote in Climbing in 2006 that the Salathé “marked the beginning of the current trend of free climbing on the big walls of Yosemite.”

In 2006, on NPR’s Weekend Edition, Piana recalled, “It was something that the climbing world hadn’t considered as possible … [W]e believed it just enough to continue trying. And we tried and we tried and we tried.” Their vision and perseverance cleared the way to free climbs on the biggest walls on the planet, from Greenland to the Yukon to the Karakorum.—Pete Takeda

1993: Lynn Hill Frees the Nose

The iconic Nose of El Capitan is, today, arguably the best-known big wall in the world. But more than three decades after it was first established, in 1961, no one had ever free-climbed it—until Lynn Hill came along.

Hill’s credentials at the time were supreme: trad climber, boulderer, the first woman to climb 5.14, victories at more than 30 international competitions. After winning her last event, a World Cup in Birmingham, England, in 1992, she walked away from competition with a yearning to put her accumulated skills toward a greater sum.

That same year, the 33-year-old Hill set a male-female speed record on the Nose with Hans Florine. During the ascent, Hill paused a few times to study the particulars: the shallow finger slots and the dearth of footholds beneath the Great Roof. “It’s just really desperate climbing—touch and go,” Hill says today.

Later that year, Hill was back to attempt to free-climb the route with Brooke Sandahl, who at the time had made strong attempts to free the route. The pair lowered from the top and for three days practiced the Changing Corners section, an open book of granite containing almost no handholds. Hill’s contortionist ability and skill in creating oppositional forces were well suited to pulling off the ferocious moves. A week later, she and Sandahl returned for their successful effort: 33 pitches up 3,000 feet in four days.

Her ascent resonated on many levels. It was thrilling for both men and women to hear, though especially so for the latter. Almost no women at the time could climb as hard as the top men of the day. It brought renewed national and international interest toward what new realms of climbing were possible on the big walls of Yosemite, and it helped inspire the top technical climbers to broaden their skill sets in ways still being manifested today.

The ascent was miles ahead of its time. It was not led free again for 12 years, until 2005, an unbelievable record. All these years later, only three other people have free-climbed the Nose. Only one other climber, Tommy Caldwell, has done it in a day.—Alison Osius

2000–Present: Honnold, Caldwell, and Jorgeson

2000-2008: Tommy Caldwell First Free Ascents

In June 2000, Tommy Caldwell, at age 22, made the first free ascent of Lurking Fear with Beth Rodden. It was only the fourth free-climbing route up El Capitan, and it came at a time when fewer than ten people had freed the wall by any route—most who attempted the wall were aid climbers, meaning they used fixed protection to haul themselves up. Caldwell had previously freed one of the other routes, the Salathé Wall, but Lurking Fear was the first of a half-dozen new free routes that he would put up across El Cap over the next decade. In the process, he redefined not only his climbing but also what is considered possible on big walls.

Caldwell’s routes are hard. In fact, in the 16 years since he started freeing new routes on El Cap, only one of his six routes, the Shaft, has been repeated, and that wasn’t until 2014. When he and Justen Sjong freed Magic Mushroom in a four-day push in 2008, Sjong, an accomplished El Cap climber himself, had to rest for a month afterward. Caldwell returned a week and a half later and freed the route in a day. It might be the most difficult route ever climbed in a day, owing to the fact that the hardest pitches—the majority of Magic Mushroom is rated 5.12 and higher—are toward the top of the 3,000-foot wall.

Caldwell also became the first person to free-climb El Cap twice in a day when he climbed the Nose and Freerider back-to-back in 23 hours and 21 minutes in November 2005. Though neither was a first ascent, the amount of vertical feet and consistent difficulty blew the climbing community away.

His ascents were a big part of what inspired me—and, frankly, an entire young generation—to free-climb on El Cap. No longer is El Cap assumed to be solely the realm of aid climbers, and Caldwell has been the driving force behind that change. He has normalized free climbing on big walls. It’s somewhat ironic, given that the routes Caldwell has put up on El Cap are too hard for anyone else to climb.—Alex Honnold

2008: Honnold Solos Half Dome

The core concept of the epic superhero movie X-Men is that life generally evolves very slowly, but every once in a while, evolution leaps forward. Yosemite provides the perfect setting for such a step in rock climbing—it waits for someone with the imagination and firepower.

Alex Honnold burst onto the scene in 2007, becoming the second person to solo the linkup of Astroman and the Rostrum, 20 years after my ascents. That it took so long to be repeated might seem strange to some, but one should keep in mind that at no time are herds of soloists scrambling over the walls there. It takes a particular mind-set to commit to being alone in such a vast landscape—one capable of determining actual from perceived risk and overcoming the fear of falling.

What Alex was then able to do, and I was not, was think bigger. Instead of tiny increments of size and difficulty, he went for a bold stroke: Half Dome.

This is not quite as madcap as it sounds. Alex was not on some suicidal bender from a failed romance or mind-altering drugs. He approached the enterprise as rationally as one can when stepping into outer space. In early September 2008, he climbed the face of Half Dome with a rope and climbing partner—like just about every other climber does—to make sure there was some sanity in his craziness. Two days later, he was back. Alone.

It’s hard to convey how magnificently huge Half Dome looks when standing at its base. It is as wide as it is tall, flat like a movie screen, and soars 2,000 feet straight up, impossibly high.

For the climb’s first 1,900 feet, Alex was more or less on cruise control. The granite rolled by smoothly. Then, about a hundred feet from the top, he paused at a final blank slab. Much of the climb consists of steep cracks where any slight nervousness can be compensated with brawn. Here, at the end, it was all delicate footwork on slopey ripples, a place where tightening up means failure, and Alex had a moment of crisis. Time stretched out, and he fought to keep his composure from unraveling.

Standing there, Alex spied a protection bolt nearby that happened to have a carabiner attached. He poked a single finger in—not to pull on, but to arrest in case of a slip. Alex’s cool clicked back into place, and he continued up to the summit as simply as he’d come.

The biggest breakthroughs in climbing are more mental than physical. But they begin as ideas. The source of Alex’s achievements, I think, is heart—the ability to dream large. —Peter Croft

2012: Honnold Solos Half Dome, Watkins, and El Capitan in a Day

Now I’m safe. Now I’m not.

That was the mantra that ran through Alex Honnold’s head on June 5 and 6, 2012, as he tried to link solo ascents of the three biggest faces in Yosemite—the south face of Mount Watkins, the Nose route on El Capitan, and the Regular Northwest Face route on Half Dome. He was safe during the short bursts of daisy soloing, as he clipped long slings to fixed pitons and cams he inserted in cracks. He wasn’t as safe during the long stretches when he free-soloed, with nothing but his fingers and feet connecting him to the world of the living.

Two weeks earlier, Honnold paired with Tommy Caldwell to as they climbed all three faces in 21 hours and 15 minutes. Every move they made on the 7,000 feet of sheer granite was free, with not a single point of aid—no hanging or pulling on pitons, cams, or nuts. They were roped throughout, but simul-climbing for hours—meaning both men were moving at the same time—through fiendishly difficult sequences with only a piece or two between them to prevent a doubly fatal fall.

The Yosemite Triple would have been the zenith of most climbers’ careers, a deed to rest on for a lifetime. For Honnold, doing it with Caldwell was “kind of a warm-up,” he said.

Starting at 4 p.m. on June 5, Honnold dispatched Watkins in the blithe time of 2 hours and 20 minutes. It was dark by the time he launched out on the Nose, and he forgot his chalk bag. A thousand feet up, he managed to borrow a bag from a bivouacking climber. “Putting my hand into it felt orgasmic,” he recounted.

Cruising the Nose in total darkness, with the universe reduced to a headlamp cone, seemed weird. “There are all these creatures that come out,” he says. “Bugs, mice, bats, even frogs that live in the cracks. And these giant centipede insects. I was worried I’d step on one and splooge off.”

Fatigue hit Honnold hard on the grueling scramble up to the base of Half Dome later that night. But he got into a rhythm, climbed past a number of strangers, and topped out just before 11 a.m. on June 6. Total elapsed time for the three walls: 18 hours, 55 minutes.

As with most of Honnold’s “firsts,” nobody else has even attempted to duplicate the feat in the four years since the . “Soloing big walls is fundamentally scarier than soloing free routes,” he says. The myth surrounding Honnold is that he’s incapable of fear. But, he says, “At the top of the Nose, I got into some crazy positions. Free-soloing this endless hand crack. It wasn’t that hard, but, Jesus, it’s scary up there.”—David Roberts

2015: The Dawn Wall Goes Free

Last year’s first free ascent of the Dawn Wall by Tommy Caldwell and Kevin Jorgeson is etched into the mental landscape of the American public.

The 3,000-foot vertical granite sheet on El Capitan had been climbed hundreds of times, but climbers had always used nylon ladders, like you’d use an extension ladder to change a lightbulb. Aid climbing, as it is called, is an anything-goes form of ascent, and for 45 years it was considered the only way to scale the Dawn Wall’s mirror-smooth granite. As far as anyone could see, there were no holds on the route.

Caldwell and Jorgeson saw otherwise.

Free-climbing the Dawn Wall took the pair six years of on-and-off effort to find and solve its Rubik’s Cube of puzzling holds. One section on pitch 16 was so blank that Caldwell built a replica back home and practiced jumping past that bare stretch. He figures he rehearsed that leap hundreds of times and “did it maybe once.”

Jorgeson’s challenge was about halfway up, on pitch 15, a meandering sideways stretch with holds like Ginsu knives that he could grip only at night, when the rock was cool. He battled this section for four days. Each attempt sliced his fingers, requiring superglue to patch them back together. At one point, Jorgeson had to rest for two days to let his skin regrow.

After a week of being stuck, he punched out the crux and joined Caldwell for the final section. With cameras rolling—the summit bid unfolded on a live Internet feed—the two topped out after 19 continuous days on the wall.

On top, Jorgeson and Caldwell toasted with champagne and faced , which had been covering the climb for weeks, as had just about every media outlet. In all, according to Adidas Outdoors, the free ascent of the Dawn Wall generated billions of online impressions—by far the most coverage and greatest reach of any climb—and was hailed as the most difficult rock climb ever achieved. Practically overnight, the Dawn Wall became a topic for dinnertime conversation, and the two climbers became so in demand that they and the battery company Duracell got Jorgeson to .

The Dawn Wall reestablished Yosemite as the epicenter of rock climbing and let it show off two indomitable climbers who represent the best of the American spirit. —Duane Raleigh

Footnote: We know: events, climbs, and personalities salient to Yosemite’s trajectory have gone missing. Where, for example, is the Steck-Salathé? Or New Dimensions? The Zodiac and the south face of Mt. Watkins? What happened to David Brower, Allen Steck, Jim Bridwell, Dale Bard, Charlie Porter, Ray Jardine, Hans Florine, and Dean Potter? Where’s the 1977 plane crash that lined dirtbags’ pockets with ill-got gains? Well, mea culpa. Nature’s got limits, and so do we. Hopefully our tick list has piqued your interest and whetted your appetite for more of Yosemite’s climbing history.