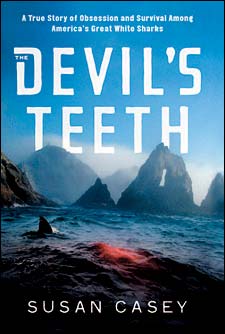

Though they lie just 27 miles off the coast of San Francisco, the ragged, desolate Farallon Islands are home to the thousands of sea lions and seals that make good eating for one of the world’s largest concentrations of great white sharks. In The Devil’s Teeth: A True Story of Obsession and Survival Among America’s Great White Sharks (Henry Holt, $25), journalist Susan Casey (���ϳԹ���‘s creative director from 1994 to 1999) recounts several visits to the foreboding, fog-shrouded archipelago, where she followed a pair of biologists—two of only a handful of humans permitted to visit the protected islands each year—as they tagged and studied the mysterious 17-foot predators. Florence Williams recently caught up with Casey, who’s finally gotten her land legs back.

Devil's Teeth

Devil’s Teeth

Devil’s Teeth

���ϳԹ���: On a clear day, you can see the Farallon Islands from San Francisco—yet actually getting there sounds like quite an ordeal.

Casey: It’s not a pleasant day trip. The islands are on the edge of the continental shelf, and so craggy they look like something out of Dr. Seuss. The currents converge here, so they take tempests full on, from above and below. All that turbulence is part of what’s kept them wild.

What drew you there—were you more into the predators or the ocean?

Oceans are my thing—they are full of amazing mysteries. The rockets we send into deep space are really going the wrong direction. There are worlds we don’t know anything about.

You describe ongoing tensions between the researchers and a cage-diving company that operates in the Pacific Ocean near the Farallones. Does cage diving hurt the sharks?

Not if it’s done right. And the second anyone eyes a great white, their thoughts about them change, which is important. Sharks are not just relentless eating machines; they’re much more complicated and awesome than that. There’s no time to lose for them—the World Wildlife Fund just named great white sharks an at-risk species, thanks to unregulated international trade.

You had some strange experiences in the Farallones, sleeping in an old, guano-covered lighthouse and getting trapped on board a sailboat. Do you think the place is cursed?

Cursed is too strong a word. But definitely haunted. It’s like the back side of the moon out there. I was totally naive about it, and I got walloped.

What was it like to “lose” someone else’s yacht?

When it happened, I thought the world had ended. I felt like I should crawl under a rock for a month. But then a very brave salvager rescued the boat, and the insurance company paid for damages.

Your last visit was unsanctioned; you were breaking U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service rules by even stepping foot on the islands in the Gulf of the Farallones National Marine Sanctuary. Did writing the story justify that?

In retrospect, I did go too far—obsession settled over me. I thought I was doing the right thing and had my bases covered, but the place had other ideas. If I could do it over, I would do it differently. But I’d have a different book.

Your creepy antique Ouija board survived the whole adventure. How did you finally get rid of the thing?

I stuffed it under the bed at the Four Seasons in Los Angeles