The Buddy System

Behind every great adventurer is the support and irrepressible taunting of a good friend.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

We aren’t asking you to hold hands and tell each other how you feel. But admit it: when you’re stuck under a leaky rain fly with nothing but a wet pack of matches and your own soggy thoughts, solitaire loses its appeal. Call them your posse, your entourage, whateverтАФbut know that the best friendships in life are forged in the wild and on the road. In the pages that follow, ║┌┴╧│╘╣╧═Ї celebrates the power of twoтАФor, if you can’t stand to be nice, the joys of a really bad feud.

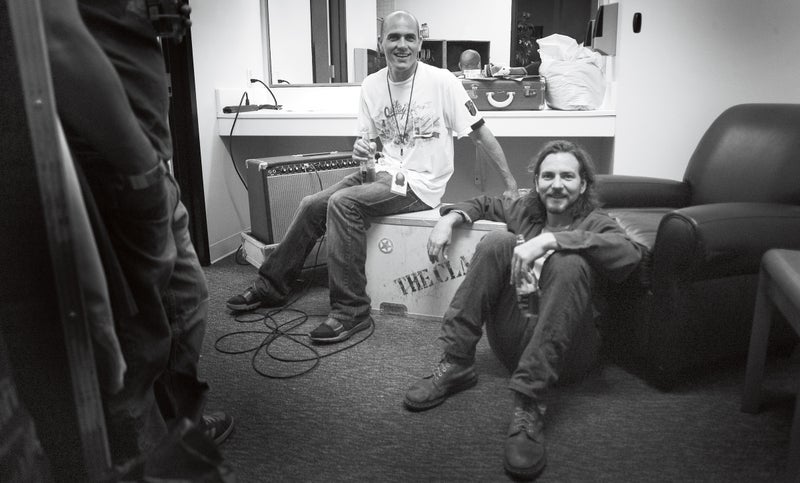

Even Flow

Pearl Jam frontman Eddie Vedder is an avid wave rider. World champion surfer Kelly Slater is a closet guitarist. Together they’ve formed a mutual admiration societyтАФone based on music, travel, and regular board sessions from Hawaii to Australia. Recently, ║┌┴╧│╘╣╧═Ї associate editor Anthony Cerretani caught up with the pair between sets.

OUTSIDE: What kind of friendship do you guys haveтАФblood brothers, distant cousins, partners in crime?

Slater: Strictly business.

Vedder: Yeah, I’d take a bullet for him, and yet he does his best to kill me in the surf.so

Slater: I would take a splinter for you, man. Anytime.

How did the friendship start?

Slater: Back in ’92, I was in Africa, and I really sat and listened to Ten, Pearl Jam’s first album. It had a real connection with surfing. I didn’t know anything about Eddie; I didn’t know if he surfed or where he was from, any of that. I always knew somehow we’d end up being friends. But we didn’t meet until ’96, when we were both at a Grammy Awards party.

Right when your career was skyrocketing. Was that the connection?

Slater: When I first started winning, I wasn’t in control of my stuff like I should have been. You’re really not sure what the “top” is, then you get there and maybe it’s not all it’s cracked up to be.

Vedder: If you’re up in the clouds on this ladder that leads to nowhere and it stops in the middle of the sky and there’s no one else around, and you look around and see this other guy 50 yards away and he’s got a ladder that’s popped up through the clouds and he’s up there looking around, it’s like two guys waving: “Hey, how’s it going? Are you doing OK? Are you going to stay up here? You want to go down? Let’s go down. Let’s go surf, let’s play.”

And things just evolved from there?

Slater: I don’t think we exchanged numbers or anything like that at the time. We made a connection, but it wasn’t until a year or two later that we ran into each other in Australia.

Vedder: Yeah, we didn’t really date until the late nineties.

Slater: I kept seeing him, but we weren’t “seeing each other.” Seriously, we didn’t become friends until we understood enough about ourselves and our lives for it to mesh really well. Eddie’s at the top of what he does, and I’ve been fortunate enough to have the same kind of success, so there’s a familiarity with surrounding circumstances and how to deal with them. You recognize the same things in each other.

What brings you together now?

Vedder: The ocean and musicтАФthat’s what supplies the bond. Maybe he can learn a few bits from me musically, although he’s really established with the way he can play, as opposed to me with my surfing. It’s like a clinic to be around Kelly with the waves.

Slater: There’s so many different places that we end up meeting up or having connections with. One time Eddie wanted to go to Florida and surf, and I couldn’t be there, so he just met up with my brother. Even those times are like being together, because you’re sharing those common people.

How often do you actually see one another?

Slater: We might see each other a few times in a year and then we might not for a year. It’s here and there. When you know your friends are going to be somewhere in the world and you’re going to be close to there, you make it happen.

Vedder: I can’t think of anyone I’ve ever met who’s more of a citizen of the world than Kelly. The interesting thing is thatтАФsorry, KellyтАФyou don’t really sit still, ever. Even when you’re sitting down, you’re moving. It’s a tremendous force to be around. He just travels the world and, wherever he shows up, it’s like an old John Wayne movie: Everyone knows him. He could be in South Africa, Australia, Tahiti, anywhere. And everyone’s so happy to see him.

Slater: You know, it’s hitting me full on right now because I travel so much. I’m just a shooting star at this point. It’s going really fast and I’m getting to see all this stuff and cover a lot of ground, but I maybe don’t quite get the connection I want with the things that really matter.

Vedder: Well, the nice thing when you do settle down is that you’ll be able to sit on the porch and have no regrets about things you could have done and places you could have gone. You’ve done it.

Describe a typical Eddie-and-Kelly surfing session.

Vedder: He’s gotten me in some pretty hectic wave situations. They’ve also happened to be some of the greatest moments of my life. I relish every second we have together, whether it’s playing ukuleles or talking about fin design or figuring out how to capture a wave by looking at maps on the Internet or charts on a kitchen table.

What about just hanging out?

Vedder: A lot of friends or familyтАФif you get together, you get a rack of beer and a few bottles of wine and talk about the past and you’ll laugh and have a great time. With Kelly, you won’t be sitting down talking about things you’ve done. You’ll be doing things. Unforgettable stuff. There’s new life being created and new memories. And we’ll always end up playing music. I could sit around in Seattle with some of the greatest musicians in the world and we’ll never play music, but with Kelly, it always happens. Around campfires, in the living room, whatever.

Slater: For me, that’s an inspiration in itself. You know, to play with you. It’s not often in life that people get to meet someone they think so highly of and then become close friends.

Sounds like a case of reciprocal hero worship.

Vedder: I think that’s unspoken and you’re making us feel very uncomfortable… [Laughs]

Slater: I’m actually not uncomfortable with that at all, because I’ve had that with Eddie since way before I knew him. It’s not something I’m ashamed of.

All the shared surfing and musicтАФis it therapy?

Vedder: For Kelly, I see music as being like a religion.

Slater: I just couldn’t live without it. Literally. Playing music every dayтАФit’s like eating food. Lately, I’ve been doing it more than I’ve been surfing, by a long shot. It’s my outlet for what I can’t express in surfing.

Vedder: And I think surfing is kind of my religion. Kelly felt the connection to the water in our first record, and he didn’t have a clue that half those songs were written in the water. That’s where everything for me always comes from. When I’m spentтАФI’ve exhausted all my accounts and the interest is goneтАФall I have to do is get in the water for a few days, hopefully a month, and then I’m back in the black. It’s absolutely a necessity for both of us: music for him, water for me.

Does that make it strange to watch each other perform professionally?

Slater: When I hear “Eddie Vedder,” it’s not just a person; it’s this thing that people have ideas about, that they love or praise. They grew up with the music. So, yeah, it’s funny to be sitting on the side of the stage watching the whole thing happen. You’re seeing your friend, who has done something so important and means so much, having all those people know him at an intimate level and, at the same time, not know him at all. I guess I have that in my own world, too.

Vedder: I remember one time we were out paddling on some little waves in Hawaii and there was a dad with his seven-year-old on the front of the board. And the dad paddles up and he sees that it’s Kelly and his eyes get big as saucers. He’s so excited. Sometimes people ask you for more. Kelly will deliver on all ends. He’s an incredible ambassador for the sport, he’ll never let anybody down. He’s really giving in that kind of way.

So who’s got the better job?

Vedder: I’ve got to give it to Kelly. Because he doesn’t have toтАФcareful what I say here… Pittsburgh’s great, and Cincinnati’s great, butтАФ

Slater: Leave it at that. And yeah, I would have a tough time saying anyone has a better job than I have. I get a salary to go surf around the world.

Vedder: This might be my only thing that I’ve got on Kelly: I can create my own schedule. The band will democratically agree on a touring schedule; when Kelly’s on the tour, he has to be there.

Slater: But you don’t have the most admirable hours.

Vedder: Well, yeah. I just don’t sleep.

Kelly, you recently played “Rockin’ in the Free World” with Pearl Jam onstage in San Diego. What was that like?

Slater: I’m going to give the moral to the story here. The moral is that everyone deserves a second chance in life. Eddie actually invited me onstage in ’99 and I totally wussed out.

How did he do, Eddie?

Slater: I did pretty average.

Vedder: No, no, no. Sparks were flying. I think that honestly, with no sarcasm, it was greatтАФhe was cool and calm and collected and loud. It wasn’t any kind of air-guitar display. The man can handle himself on a big rock stage.

Compare the energy of a packed house and a big wave.

Slater: The fear onstageтАФit probably affects me more physically. I get nervous. But the actual danger level is not really thereтАФunless you’ve got a heart condition.

Vedder: With a packed house, unless you say something incredibly offensive to God or country, a crowd of 15,000 people will not kill you. I guess they could if they wanted to, but they will not all jump on you at the same time and hold you down for two minutes. That’s the difference between a big crowd and a big wave. When Kelly takes me to Waimea Bay, that wave does not give a shit who I am.

тАФAnthony Cerretani

Cover Me

Friends for more than a decade, bestselling authors and war reporters Scott Anderson and Sebastian Junger have survived combat zones from Afghanistan to Chechnya. This summer the two pulled up barstools at the Half King, the Manhattan saloon they opened in 2000, to talk about luck, loneliness, and the fine art of two-and-a-half-day stubble.

I. Panama

A humid summer night at the Half King, on West 23rd Street. Junger arrives at precisely 6 p.m., in blue jeans, a polo shirt, and black boots. Anderson shows up 15 minutes late, in a ratty T-shirt, shorts, and flip-flops. He looks like he just mopped his kitchen. We’re all sweating. Scott the most. The conversation quickly turns to one of their favorite trips.

Anderson: I was doing a story in Panama, and Seb came down to hang out with me. I think you were kind of appalled by my journalistic style. Turns out I don’t really speak Spanish.

Junger: So I was the translator.

Anderson: And it also turns out I forgot to bring a notebook. Or a pen.

Junger: I provided him with the basics.

Anderson: We went out to this island off the Pacific coast. Half the island was a nature preserve, the other half was a free-range penal colony.

Junger: The guards lock themselves in at night, and the inmates have the run of the island. It’s very Lord of the Flies. We hired this big old wooden diesel fishing boat. At the dock, we ask the captain, “How long does it take?” About four hours. So we start chugging away. Three, four, five, six hours go by. Finally, Scott says to him, “I thought you said it was four hours.” And he goes, “Well, that’s in a fast boat. This boat is 12 hours.” So we got out a bottle of tequila and a chess board. And we drank the whole bottle. It was this beautiful tropical night, we were just lying on the deck. And the moon started looking really weird. And it got weirder and weirder. We finally figured out it was a lunar eclipse.

Anderson: That’s one way we’re different: this Boy Scout impulse in you. You got incredibly excited about the eclipse.

Junger: Still am.

Anderson: I have no science background. He spent two hours trying to explain this thing to me. He had to draw charts. And I looked at him, saying, What the fuck?

Junger: He still doesn’t believe me.

Anderson: I still don’t.

Junger: Then on the way back from the island, Scott was getting onto the boat and he slipped on the gunwale and cracked his rib. He was in a lot of pain. I remember thinking, If your friend is hurt, you’re supposed to take care of him, right? I mean, if he were a girl or if I were a girl, that caretaking would be obvious and easy and not awkward at all. But with two guys, it’s actually a little weird.

Anderson: There’s not much to do for a broken rib.

Junger: Essentially, I did nothing. I mean, you were fine.

Anderson: I smoked more.

II. We Never Fight. Really.

In which the guys claim to share an “unspoken familiarity” and to be “wired similarly.”

Anderson: I don’t think we’ve ever said a harsh word to one another.

Junger: It’s true. We haven’t even come close to an argument. We both completely avoid conflict as much as possible. We’ve also never been in an active war zone together.

Anderson: We did do one story together where we took opposite sides of a conflict. It was in Cyprus about eight years ago, and we both wanted to be with the Turks. We settled it by flipping this old Greek coin from Sebastian’s family.

Junger: I think I still have it. [Searches beat-up wallet] I may not, but I might. I do.

Anderson: I’ve got a confession to make. The thing I knew from childhood and flipping bottle caps hundreds of times is that anything that’s bowed out on one side, like a bottle cap, will come up topside like nine times out of ten. See, look at this coin, it’s concave. It’s practically guaranteed to end up tails four out of five times. So I won the coin toss. And I never shared that with you.╠¤

Junger: We’re about to have our first conflict.

III. My Space

People at the bar recognize them, but nobody stares too much. A few friends stop by to say hello. Anderson nurses a couple of iced teas, then a beer, while JungerтАФtwo months into a sabbatical from alcoholтАФsticks to nonalcoholic Bucklers.

Anderson: Our original idea was to buy a building over in Red Hook [in Brooklyn]. We were going to have apartments on the upper floors and a fireman’s pole down into the bar. We’d come down, hang out, then get winched up at the end of the night.

Junger: We were imagining a pulley system to get back upstairs. We’d each have a floor, there’d be a crash-pad floor with a pool table for our friends, and the ground floor would be the bar.

Anderson: It’s like the ultimate bachelor pad.

Junger: The idea was to have it just break even and pay the mortgage, so we wouldn’t have to be business owners. That didn’t survive scrutiny from, uh, others.

Anderson: Girlfriends.

Junger: Yeah…

Anderson:╠¤You╠¤always think of worse ideas in collaboration with someone else than you would ever come up with on your own. And yet, somehow, the Half King worked. One of the things about doing our kind of journalism is that when you come back, there’s such a disjuncture. You were based in Darfur or Afghanistan and all of a sudden you’re dropped back in New York. It’s very difficult to explain what you’ve experienced. So to have that place where you can get together with people who do similar thingsтАФthat makes it less disorienting. This place is much bigger than we had envisioned and much more of a general-population bar, but journalists all over the place know about it. I was in Libya and this English journalist started talking about this really cool bar in New York. I said, “What’s the name of it?” And he said, “The Half King.”

Junger: We didn’t want a literary salon. And we didn’t want a place that was obnoxiously journalistic. Most of the people in here right now are not journalists. But very often when journalists congregate, they come here.

Anderson: Especially photojournalists, it seems. Maybe that’s because they’re more noticeable, because they’re louder. Junger: They drink more.

IV. You Complete Me

More than an hour after we start talking, a table opens up out front, where Junger and Anderson can smoke. This they do with abandon.

Junger: We don’t talk about relationships that much, and we certainly don’t talk about our own relationship very much, and, uh, now’s our chance.

Anderson: I think this was just intuitiveтАФwith me, at least thatтАФfrom very early on, there was a lot that was very similar about us. Including vulnerabilities that were buried under bravado, or sort of always appearing open and outgoing.

Junger: Both of us are very careful not to reveal that anything is wrong. We both present an exterior where everything is fine. And we both emotionally play our cards very close to the vest. We’re like cats. You can pet the cat, but ultimately the cat doesn’t really give a shit whether you’re there. And we can both have that effect on peopleтАФand probably on each other.

Anderson: I have a question for you. I bet I know the answer, but I’ve never asked you: Were you a sickly kid?

Junger: When I was very, very young I was. And then, because my father’s a hypochondriac, I decided at age ten that I was going to be robust and athletic. And then, after that, I’ve never gotten sick. But at first I actually had a ton of health problems.

Anderson: I had really severe asthma. To the point where I had to be rushed to the emergency room a few times. So I always had this sense of being somehow apart from other kids. I did the same thing you did: I never wanted to show any physical weakness; I never wanted to show any physical pain.

Junger: Also, we both came from really weird families. My dad is French; he grew up all over Europe, and the family really reflected that, so I always felt like I was outside my peer group. And you just had a weird childhood, by any standard.

Anderson: I grew up in AsiaтАФmy dad worked for USAIDтАФand we were constantly moving. I also think having mothers that were creative… Your mother was a painter, and mine was a children’s-book writerтАФ

Junger: I didn’t even know that. See, we don’t talk. You know, now that we’re being forced to examine ourselves, which is a good, healthy thing… My family wasn’t very close at all, so I never felt included there, either. I grew up a really solitary kid. And when you grow up solitary, your worst fear is that you’ll be alone. And you cover that up by trying to convince yourself that you don’t need anybody. So you don’t get married at 23; you get married in your forties, like both of us did. So my question to you, because I’m just starting to understand this in myself, is: You seem very complete, and like you don’t need closeness. But at your core, are you scared of being alone?╠¤

Anderson: Good question. You know, probably. I had the added thing of growing up in cultures where I couldn’t understand or interact with the world around me. You create a sense of autonomy. It’s always been a sense of perverse pride: I’m utterly self-sufficient; I don’t need anyone. It can be couched in this way of not wanting to burden somebody.

Junger: Right. Or limit yourself. Because we’ve both had lives with a series of girlfriends, never settling down, running around doing foreign reporting. It all looks to the outside quite impressive and autonomous. But at its core, it’s not. It’s really a defense. My other question to Scott is: Is he truly the completely independent person that he appears to be?

Anderson: I suspect I’m not. But things are so intense now. My brother [Jon Lee Anderson] is a journalist, too, and he just left for Baghdad again today, and anytime my brother is in Baghdad, I slip into a different mood. And it’s never anything I say to him, but if something were to happen to him, it would… I think about it all the time. So, no, I am probably not as autonomous, but I would never express it. Junger: Until now. For an audience of millions.

тАФAs told to╠¤║┌┴╧│╘╣╧═Ї╠¤senior editor Michael Roberts.

Who You Want to Run With

Can the wildest whitewater in Montana turn back the clock for a pack of lifelong paddlers? Not exactly, but it sure can ease the pain.

My friend Nate Cross was turning 40 and wanted to take a river trip. The months leading up to his birthday had been tough. After 15 years his dog had died. That was five years longer than he’d been married. For a few weeks, Nate had carried photos of Junction in his shirt pocket and showed them to bartenders and waiters and cashiers. He told me that when he added up all the miles he’d walked with that Lab, it was about the same distance as circumnavigating the globe.

We all needed a river trip. That’s how we know each other: Nate and Adam and Ken and I had guided together for Outward Bound in Utah and West Virginia and Alaska and Baja. Now those days of living under tarps are five years behind us, and we all live in housesтАФwhich we actually ownтАФin Missoula, Montana. Ken Miller is 38, and he and his wife just had their first daughter. Adam Duerk is 37, practices law, has twin boys, and might someday run for office. Neither of them had been on an overnight river trip since their kids were born.

So on a cloudy evening in June, after a day of thunderstorms that delayed our chartered six-seaters 12 hours in Kalispell and left us with a $300 bar tab, we and four other friends landed on a strip of grass in the thick forest headwaters of the Middle Fork of the Flathead River, in Montana’s Bob Marshall Wilderness. During those long northern summer days, it stayed light until 10 p.m., and the pyramid peaks in the distance still held gulches of unmelted snow. The river was shallow and cold, gurgling between cobble islands before gathering in a channel and slipping past.

We were about to launch on one of the last real wilderness rivers in the lower 48. The only way in is by bush plane or horseback, and the way out is over 23 miles of Class IV whitewater through the habitat of grizzlies, moose, bald eagles, and mountain goats. But we were prepared. Between the eight of us, we’d racked up 70 seasons of guiding experienceтАФ50 among Nate, Adam, Ken, and me aloneтАФand on top of that we had two rafts, four kayaks, six cases of beer, seven bottles of small-batch bourbon, one pistol-grip shotgun, and a gorilla suit.

As for me, the youngest, having neither wife nor child, I didn’t have a good excuse for not getting out much. I’d lived the past two years on the East Coast and, since moving to Missoula in 2005, had been sequestered in my house writing a novel. Although the town is teeming with fresh-faced, cheerful outdoor types, I’d fallen instead for the token city girlтАФshe’d never been on a raft or a snowboard or a mountain bike and frankly didn’t see what the big deal was. She met my declaration of love with one part amusement and one part detachment, lit a cigarette, and said, “What am I supposed to do with that?”

So I wrapped my heart in a waterproof bag. Forget all that crap about finding yourself, communing with nature, and camaraderie with the boys: I fled to the wilderness this time, as always, to escape the anxiety and tedium and heartbreak of trying to live like a normal person.

On a sunny, crisp morning, we pushed off from Schafer Meadows and headed downstream. Ken and Adam and I were in kayaks; Nate was rowing one of the rafts. The rest consisted of Damon Yerkes, 46, another former Outward Bound guide, who owns a gear shop in Donnelly, Idaho; Tiff Barton, 36, who’d managed OB’s Baja sea-kayaking program; Doug Pollock, 40, who after many years at OB lives in Denver with his wife and daughter; and Bruce Allen, 45, a former Glacier National Park ranger who builds cabinets in Missoula.

The river was fast and bony and the rafts kept getting hung up. Nate missed a move and found himself stuck in a channel blocked by a downed log. After some negotiation we tied a rope to the log and yarded on it until we could slide the raft underneath and continue on. We ate lunch on a cobble beach, lying out on warm rocks. “Where is everybody?” Nate asked. We wouldn’t see another person for the entire three days.

By afternoon the clouds had returned and a steady rain had started, one that would last for 24 hours. The river got wider and deeper; we saw fewer exposed rocks and more crashing waves, and there were long deep stretches where the current surged between swirling eddies on either side. We found a good camp and stretched a tarp and huddled around the stove, spiking the hot chocolate with Kahl├║a and vodka. Adam slipped into the gorilla suit. “For warmth,” he said.

Adam has a nonironic zeal for the timeworn symbols of manliness (pickups, guns, flasks) combined with a wholehearted love of corny jokes, and if this circus had a ringleader, he was it. Adam and Nate and I had gone through instructor training together at the Colorado Outward Bound School in 1996. While many of us were there to acquire something called “leadership skills,” Adam seemed to have been born with them. He’d already been teaching kayaking for ten years and had a confidence and serenity that I would later attribute to his Quaker upbringing. He could look the most hapless, awkward teenager in the eyes and say, “I know you can do this,” and actually mean it. As the Quakers say, he knew how to hold someone in the light.

Nate was already 30 then. Between owning his own hardwood-flooring business in Denver and marrying his girlfriend, he was past the point of thinking that taking kids into the woods would be a viable career. He saw it as a way to have fun. Nate is an old-fashioned surly New Englander; he plays hockey, builds boats, and has never used e-mail in his life. Over the years, he’s picked up the nickname All-Man.

Ken is the only one of us who actually grew up in the country, tramping the Wisconsin woods with a gun and a dog and a fishing pole. He’s one of those people who seems to be good at all useful tasks, from catching fish to telemark skiing to fixing broken lawnmowers. But you can’t really pin him down. On one hand, every fall he’s out hunting with his bird dog, Bubba; on the other, he has a degree from an art school.

From Utah, we were promoted to Alaska and Baja. It was almost more freedom than we could bear: dispatched to Mexico with a fleet of Ford F-350’s and more gringo dollars than you could hope to spend in places like Loreto and La Paz. Every fall we’d drive the rigs from Moab down to Loreto, then come back in the spring. The truckbeds were piled high with hardtack crackers and peanut butter, and the drivers packed a stack of girlie mags to hand out at ▓╘▓╣░ї│ж┤╟│┘░ї├б┤┌╛▒│ж┤╟ checkpoints so the teenage guards with their machine guns might let us pass undisturbed.

But ultimately the dirt in our food and the dust in our teeth got tiresome. Adam convinced one of his former studentsтАФan attorney in San FranciscoтАФto quit her job and spend the summer hanging around trailers while he finished up with Outward Bound. Then they moved to Missoula and got married and the next thing we knew he’d cut his hair and shaved his face and enrolled in law school. Meanwhile, Ken was still logging more than 250 field days a year, a feat made possible by the fact that he was often paired with his girlfriend, a Canadian instructor. When her work permit expired, Ken hustled her down to the Moab courthouse and married her. With Adam’s urging, they came up to Missoula. Nate followed in 2003.

I was the final holdout. That year I finished my last Alaska Outward Bound course and went east to work on a presidential campaign. We lost, and when my sublet expired and I faced the specter of buying furniture, I flinchedтАФand succumbed to the tractor beam from Montana. After all, my friends were there.

It had been years since I ran a river with just men. I was starting to remember why. When you take eight perfectly nice middle-aged guys, drag them into the woods, and add 15 gallons of alcohol, they revert instantly to a savage state known as Mancamp.

“Who’s got the fucking Knob Creek?”

“If it was in your ass you’d know it.”

“Bite me.”

“You’d like that.”

I’d never been able to match these guys at the bar, and now as they gulped bourbon from the bottle and chomped cigars, I felt the gulf widen. My days in Brooklyn had softened me, sipping wine in bistros where not a single animal head was mounted on the walls. I had become sensitive. I had subscribed to The New Yorker. All I wanted to do was kneel among wildflowers, composing verse about love lost. I might as well have been wearing hair gel.

Mancamp is oppressive, a whirlpool of barbarity that sucks us in and holds us there. But attuned as I was to the sensitivity of the human condition, I noticed that I wasn’t the only one longing for something else. At dusk, Ken disappeared; he returned after dinner, soaked to the skin, having charged into grizzly country in the downpour and located a good fishing lake a few miles up the slope. In the morning Mancamp resumed, but as we marched up to the lake with fly rods and beef jerky, instead of leading the charge Adam spent the day by himself, surfing a wave in front of camp.

I was with Mancamp as it moved up the trail. The woods were dripping, a rainforest of swollen mushrooms and spongy moss. A creek blocked with fallen logs cascaded down, and you had to speak up to be heard over it. The last of the snow was melting off the trail and we found fresh heaps of black-green bear scat.

At the lake the fish weren’t biting, and after a while the rain returned and most of us dispersed. Bruce set off hiking alone. Nate and Doug headed back. Damon and I scrambled up a cliff band and got lost. Ken and Tiff bushwhacked along the lake to the mouth of a rushing creek; there, in a pool partly dammed by fallen spruces, they started pulling them out. Cutthroats: 14, 15, 17 inches long. In an hour they each landed ten trout.

That night the consecutive hangovers, combined with the day’s bits of solitude, diluted some of Mancamp’s aggression. It was quiet. More than three cases of beer had not been drunk. We were grilling steaks, and I asked Nate why he’d worked at Outward Bound in the first place.

“Outward Bound was just a starter kit,” he said. “That was four or five years to get to know the guys I plan to adventure with for the next 30 or 40 years. It’s the same way dogs sniff each other to figure out who they want to run with.”

On the final morning we paddled toward Spruce Park Gorge and the Flathead’s biggest rapids. Up until then, the canyon had been friendly, like someone had carved a V in a big cake, a mocha-colored loaf with spruce-green frosting. But now the mouth of the gorge looked ominous, with walls so steep that nothing grew on the loose dirt. As Ken and I caught an eddy, looking down at the sharp granite rising up on both banks, I was a bit nervous. Adam paddled over and produced something silver a flask of bourbon. “Liquid courage,” he said.

Before we launched that morning, Adam and Ken and Nate and I were walking through the woods when Adam revealed something I didn’t know. “My dad died at 50, of cancer,” he said. “His dad at 50, too, from a heart attack.” Adam was only 37, not the age to be brooding about the final end, but I did the math. Thirteen years isn’t a whole lot of time.

No one knew what to say, so we just kept walking. Adam changed the subject. He told us about this idea he has for a trailer he wants to build, so his boys can haul their kayaks behind their bikes to the new surf wave in town. It sounded like a fine idea, brimming with optimism, and I didn’t want to be the wet blanket who pointed out that the plan was a bit premature: Before hauling their kayaks to the river, the boys will need to learn to paddle, to ride bikes, and to cross the street. I mean, they’re two years old.

Just then, without warning, Adam’s feet kicked out from under him in the mudflat and, with a nauseating thud, he thumped on his back like a sack of flour.

Oh, shit, I thought. He’s dead.

I rushed over and he opened his eyes.

“I’m fine,” he said. “I just slipped.” We pulled him up. And it hit me then that for all the fretting men do about getting old, about being deskbound or mortgaged or bald, these are just symptoms. The real disease is mortality, and each of us has a terminal case. Those moments glissading down a snowfield in the Chugach or hauling a trailer down Baja’s carretera peninsular with windows down and ranchera blasting oom-pah-pah on the stereo, not much on your mind but getting to the next place you can call that youth, but more accurately it is thinking you will live forever.

There in the eddy we passed around the bourbon, then caught the current and raced downriver. The kayaks and rafts trundled down the canyon, pinging off the walls and each other, submerging in troughs and bursting through the crests.

The gorge only lasted a couple of miles, and as soon as it was over I wanted it to start again. I always want to return to those moments where past and future disappear and the present is as vivid as thunder: A wave crashes and you brace, a rock appears and you dodge it, a hole flips you and you roll back up. Across the water my friends bobbed in their boats like rescue buoys, and I was sure everything would be all right. If that gorge had never flattened out, and the river poured through it forever, we could have paddled on and on, my friends and me; we could have headed downriver, always one more bend ahead, and we would never have to die.

тАФMark Sundeen

He Said/He Said: Fishing With ‘Sandy’ and Jack

Authors Jack Handy and Ian Frazier comment on their longstanding friendship forged over fishing rods.

Jack, on Ian╠¤

Broken rods are a small price to pay

Ian “Sandy” Frazier is not only a great writer; he also happens to be my best fishing buddy in the whole world. Even though his real name is Ian, he sometimes lets me call him “Sandy,” which is his nickname. That’s how close we are.

Our latest fishing adventure would take us out into New York Harbor, which has become a surprisingly good sport fishery. We were to fish with Captain Frank Crescitelli, probably the top guide in all of New York. Sandy picked me up bright and early in his SUV, and even let me sit up front with him. Usually he wants me to sit back in the cargo area with the fishing gear, to make sure it doesn’t roll around.

Driving to the Staten Island marina, Sandy suddenly swerved into the parking lot of a convenience store. “Give me 20 dollars,” he said. I quickly complied, and Sandy was soon emerging from the store with a big doughnut, a cup of coffee, and an adult magazine. It’s weird how well Sandy and I read each other; he seemed to know instinctively that I had already eaten breakfast. And that I wanted him to keep the change.

If you have any doubts about the fly-fishing dexterity of Sandy Frazier, you should see him balancing a coffee and a doughnut, and reading an adult magazine, all the while driving at excessive speeds. That’s the kind of talent you don’t see much anymore. He even managed to field a cell-phone call from his wife, who, incidentally, used to be my wife. (Who could blame her?)

After we stowed our gear aboard Captain Frank’s boat, Sandy asked me to go back to the car and see if he’d forgotten something. “What did you forget?” I asked. “Oh, I dunno, something,” he said. I didn’t see anything in the car, and when I got back to the dock the boat was gone. I can’t really fault Sandy for taking off without me. I’d spent maybe five minutes looking through the car, and when you’re ready to fish, five minutes is an eternity.

I sat on the dock for most of the day. I enjoy being outdoors, even when I’m not fishing. I just wish I’d gotten my hat off the boat, because it was pretty hot and bright. And my sunglasses. I thought about going inside someplace to wait, but Sandy doesn’t like it if he has to look for you when he comes back. Trust me.

It’s amazing how many ants there are on a boat dock. Once your eyes get trained to them, you see them everywhere. And, unfortunately, they bite. They seem to bite you more if you try to lie down and rest, or sit down, or stand on two feet. But if you stand on one foot and then the other, they don’t bother you as much. And you can’t blame them for biting. It’s we humans who are in their territory.

I could have tried fishing from the dock if I’d had my rod, but that too was on the boat. I’m ashamed to admit it, but I was hoping Sandy was not using my rod. Dexterous as he is, he has broken about seven or eight of my fly rods. At least it always makes him laugh when he tells me how he broke a particular one. It’s too bad that some rods are irreplaceable, like the bamboo fly rod given to me by my grandfather. When I got it back from Sandy, he had tried to tape it back together with a piece of black electrical tape. The tape didn’t hold, but just making the gesture was so Sandy.

When Sandy and Captain Frank pulled back into the marina, they were happy. Sandy had caught a big striped bass and a couple of nice bluefish, all on a fly. Just hearing Sandy describe the fight those big fish put up made my day. It didn’t even matter that Sandy had, it turns out, broken my rod. And my sunglasses.

Captain Frank asked me why I had decided to stay on the dock instead of fishing. Sandy quickly jumped in, to keep me from being embarrassed. “He just likes it on the dock,” he said, then shrugged and twisted up his face in bewilderment. “Go figure.”

I’ve been on a couple of dozen fishing trips with Sandy. Technically, so far, I have not actually “fished.” Once, on the Beaverhead River in Montana, I floated in a driftboat with Sandy for a little while before I somehow fell overboard and spent the rest of the day drying my clothes on the bank.

But fishing is all in your mind, anyway, and Sandy will weave a good yarn about the day, if you buy him dinner and drinks. If he has too many drinks, he can get kind of angry, but I’d say that only happens about half the time. Maybe a little more than that. Sandy can make you feel like you were right there with him, fishing away. You almost want to ask, “Did I catch a fish? Did I?” He makes you feel like you were a part of it. He’s that good of a storyteller. And that good of a fishing buddy.

Author’s Note: Since learning I was writing an article about us, Ian Frazier has asked me not to refer to him as “Sandy” in the piece. Or as his friend. Unfortunately, I have been told by the editors it’s too late to change anything. After much pleading, I have at least been granted this extra space to apologize. All I can say, Mister Frazier, is how sorry I am. I will make it up to you on our next fishing trip.

тАФJack Handey

Ian, on Jack

Why I love Jack, even if he does copy everything I do

Jack Handey, my old fishing buddy, is a fascinating guy. Jack first met me about 20 years ago at a party for Saturday Night Live. I’m not sure what Jack was doing at the time. I had just gone through some very painful and messy personal problems that (to give you the short version) had to do with a former business partner and his wife and a lot of petty jealousy over my Daytime Emmy nomination. I liked Jack right off because he’s a good listener. Also, I’m a very physical person, and I think we both found it reassuring that I held on to him by the sleeve as we talked.

Who really knows why people become friends, in the end? Whatever the reason, Jack took to me right away. I happen to be a tournament-level angler in both fresh and salt water (not that I fish in tournaments, but I am at that level), and Jack became interested in fishing after he met me. He’s like thatтАФI do something, he sees it, and he copies me. I say “Holy shit!” when a big fish hits my lure, and pretty soon Jack is saying that, too. I wear jeans and a T-shirt, Jack wears jeans and a T-shirt. I don’t mind. Being a friend means accepting the other fellow’s foibles. Consider Jack’s legendary forgetfulness, to cite another example. Sometimes before a fishing trip Jack will omit the little detail of calling to tell me where and when we are to meet our fishing guide, as well as the basic fact that we’re going fishing in the first place! I have to take the trouble of making the calls myself, finding out the details, and then hurrying to the dock, often with just minutes to spare.

Not a lot of people know that I’m the one who gave Jack his nickname. True, he was called Jack before he met me, but the way I said “Jack,” in expressions like “Hey, Jack, get the hell over here!”тАФit had a funny and friendly quality that changed the name completely. Developing that kind of good rapport, I’ve found, is important in a fishing companion. Guys who fish with me should anticipate what I want before I even know it myself. Say I hook Jack in the head with my backcast: He understands that he has to cut that line free immediately so that I can tie on another fly and cast again as soon as possible. When your line’s not in the water, you’re not catching anything (except, I guess, Jack).

Sometimes, of course, Jack is worse than Harry Whittington when it comes to getting out of the way. Whenever fish appear in our vicinity, Jack tries to catch them, violating the traditional fishing protocol about first looking to see where I am. I can’t count the number of times he has done that. I’m unfailingly patient, limiting my response to a quick shove with the butt of my fly rod. Even worse, when he does step to one side, and fish where he’s supposed to, he often catches fish that are smaller than I would have caught had I caught any, but surprisingly decent fish all the same. I have heard him say he has even better luck when he is not with me, but I can’t really believe that is true.

Every few years Jack sends me photos of the supposed “trophies” he claims to have caught without my help. That a grown man would engage in such transparent deceptionsтАФit’s hard to comprehend. The photos show Jack in his fishing gear at some likely spot holding in his arms a “monster brown trout” he obviously borrowed just minutes before from the wall of a bar. Awkwardly he tries to make the leaping pose in which the fish was stuffed look real. Once he even forgot to take the cigarette out of its mouth. I always play along and compliment him and act really awed. He’s my fishing buddyтАФwhat else can I do?

Author’s note: Jack Handey is actually the nicest guy, best fisherman, and funniest writer I know. I was never nominated for a Daytime Emmy, am not a tournament-level angler, and have never hooked Jack in the head. The part about the stuffed fish is (in my opinion) true.

тАФIan Frazier

The Grudge Report

Reinhold Messner and Max von Kienlin Mountaineers

- Friends Forever! Messner was a wreck after his 1970 traverse of Pakistan’s 26,660-foot Nanga Parbat, during which he lost seven toes to frostbite and his brother, G├╝nther, died, apparently in an avalanche. When expedition mate von Kienlin invited him to spend time recovering in the Munich, Germany, castle he shared with his wife, Ursula, Messner gratefully accepted.

- Oops: Messner was a terrible houseguestтАФand not because he drank milk straight from the carton. Within a year, Ursula announced that she was leaving Max to marry Reinhold. (She and Messner divorced in 1977.) Tensions flared again in 2001, when Messner publicly blamed his old teammates for failing to help him save G├╝nther. Von Kienlin fired back with a book, The Traverse, claiming that Messner had once admitted to abandoning his brother on the mountain. Messner scoffed in responseтАФ”He lost his wife to me,” he later told ░┐│▄│┘▓є╛▒╗х▒ЁтАФbut sued von Kienlin, who was ordered to revise future editions of his book.

- Is Forgiveness an Option? Unlikely. Von Kienlin is willing to talk but not, apparently, to stop with the potshots. “Messner is happy about the controversyтАФit brings him publicity,” he says. “But my dream is for all of us to stand on top of Ecuador’s Mount Chimborazo and shake hands.” Says Messner: “Von Kienlin is of zero interest for me.”

Lance Armstrong and Greg LeMond Tour de France Champions

- Friends Forever! Cycling’s once and future all-stars were dripping with mutual affection after Armstrong’s first Tour de France victory, in 1999. “That performance made up for last year’s disgrace,” LeMond told reporters, referring to the scandal-rocked 1998 Tour. For his part, Armstrong said he considered his colleague a hero: Watching LeMond win in 1989 was “the first time I thought and dreamed about the Tour de France,” he said.

- Oops: With Armstrong draped in yellow in 2001тАФand about to tie LeMond’s American record of three Tour winsтАФLeMond wasted no time in bashing him. Following reports that the Texan had ties to an Italian doctor then accused of assisting athletes who used performance-enhancing drugs, LeMond told reporters, “I would have all the praise in the world for Lance if I thought he was clean, but until Dr. Ferrari’s trial, we can’t know for sure.” He later apologized, but the damage was done.

- Is Forgiveness an Option? Not with (naturally occurring) testosterone levels this high. In June 2006, LeMond told the French newspaper L’Equipe that he’d recently testified in a legal dispute involving Armstrong and that Armstrong had “threatened my wife, my business, my life.” Armstrong, meanwhile, is playing the nut card. “Greg is just not in check with reality,” he responded. “He’s obsessed with foiling my career.”

Pip├нn Ferreras and Umberto Pelizzari Freedivers

- Friends Forever! In 1988 when they met at a photo shoot, Italy’s Pelizzari owned the record for static apnea (he’d held his breath underwater for five minutes and 33 seconds). Cuba’s Ferreras had the “constant ballast” record (with fins, he’d plunged to 226 feet). As the pals began battling good-naturedly for the “no limits” record (they traded it back and forth four times between 1990 and 1993, reaching depths from 377 to 410 feet with the aid of a weighted sled), they let reporters think they were bitter enemies. “We wanted to milk it,” Ferreras wrote in his 2004 book The Dive. “After all, without the media, we were nothing.”

- Oops: Chalk it up to oxygen deprivationтАФor the clashing of two giant egosтАФbut by the mid-nineties, the faux feud had become reality. Ferreras once refused to even stay in the same hotel as Pelizzari. Neither will pinpoint what happened. “It’s normal in any sport,” says Pelizzari. “When you compete, the challenge gets bigger and bigger, then it creates a separation.”

- Is Forgiveness an Option? If whales and barnacles can have a symbiotic relationship in the deep blue, maybe these guys can, too. “I don’t see why not,” says Ferreras. “All he needs to do is say hello.” “I’m not angry at him,” offers Pelizzari, “but you have to tango together; you can’t tango alone.”

тАФGordy Megroz

The Power of Two

Best friends dish on what brought them together, and what’s kept them that way.

Damian Benegas and Willie Benegas

Alpine Climbers

Damian’s “picky” food preferences don’t allow for much expedition-meal variety. Willie has an annoying habit of removing the insoles from every pair of climbing shoesтАФwhich he shares with DamianтАФand losing them. But the differences end there. Identical twins, born 38 years ago in Argentina, the Benegas brothers live together in Salt Lake City and have completed more than 120 climbing expeditions as a team. “We do fight,” admits Willie. “But we make up in ten minutes and go climbing.”

Big Moment: Putting up the Crystal Snake, a 42-pitch, mixed ice and rock climb on the north face of Nepal’s 25,790-foot Nuptse, in 2003.

Role Play: “I’m the minimalist, and Damian’s the gear monkey,” says Willie. Responds Damian, “I’m better on hard-grade sport climbs, but he has more control over fear.”

Young and Restless: “We grew up in a fishing village on Patagonia’s Peninsula Vald├йs,” says Willie. “When we were 12, we crossed the 40-mile-wide Golfo Nuevo in a homemade raft. We hiked five days to get home. Our mom was so mad she chased us with a broom.”

Up Next: Damian is off to Nepal and Tibet, to ski Cho Oyu, while Willie is considering his options. As Damian puts it, “We do everything to the max.”

тАФLindsay Yaw

Hilaree O’Neill and Kasha Rigby

Ski Mountaineers

O’Neill and Rigby met seven years ago in a laundromat in Chamonix, France. Since then, they’ve launched 12 major expeditions, climbing and skiing peaks from Argentina to Lebanon. What sealed their friendship, in addition to a shared addiction to high-altitude masochism? Five storm-racked days stuck in a snow cave on Russia’s 18,510-foot Mount Elbrus in 1995. “It’s not just that we climb together,” says Rigby. “We can be tired, cold, and hungry, and still enjoy each other’s company.”╠¤

Big Moment:╠¤A 2005 ascent of 26,906-foot Cho Oyu, completed without Sherpa support (read: mega load hauling).╠¤

Role Play:╠¤“I’m better at rope skills and crevasses, and I ski with more confidence,” says Telluride-based O’Neill, 33. “Kasha’s better at route finding.” “Hilaree burns hot,” says 36-year-old Rigby, who lives in Salt Lake City. “I get through by staying steady.”╠¤

The Martha Factor:╠¤“Kasha might forget that extra T-shirt,” says O’Neill, “but she always brings lavender oil so our tent doesn’t smell.”╠¤

Up Next:╠¤Northern Myanmar or the Indian Himalayas. “Our next trip will be off the beaten path,” says O’Neill. “A return to our old days of adventure.”

тАФLindsay Yaw

Heather Stephenson and Jen Boulden

Founders of Ideal Bite

They met at a New York bar in the winter of 2003. Stephenson was a confessed “corporate hack” looking to align her career with her values. Boulden was finishing an environmentally focused M.B.A. at George Washington University. They both had too many cocktails. “We were gobsmacked that we had so much in common,” says Boulden, 33, who lives in Bozeman, Montana. After a string of successful eco-business consulting projects, in June 2005 they launched IdealBite.com, a Web hub dispensing advice on green lifestyle choices and providing market research to companies target=ing the Whole Foods set.

Big Moment: Sending the very first Ideal Bite daily tip to 300 friends; today, the subscriber list is 55,000-plus. This past February, the partners netted $215,000 in a family-and-friends round of investment funding.

Role Play: “I bring in new subscribers, and Heather monetizes them,” says Boulden. “There is a definite yin-yang there. Ask either one of us to switch roles and we’d vomit.”

Blame the Altitude: “Our entire year-two strategy came out of a hike in Montana,” says Brooklyn-based Stephenson, 33. “And then we got back and frantically put everything into the laptops.”

Up Next: This fall, Stephenson will relocate to San Francisco and open a new Ideal Bite headquarters. A book is planned for next summer.

тАФKevin Kennedy

Brad Gerlach and Mike Parsons

Big-Wave Tow-In Surfers

To trust a guy enough to be your lifeline in 60-foot-plus waves, he has to be your longtime soul brother. Actually, no. “When we were on the pro tour, I was Richie Cunningham and Brad was the rebel,” says Parsons. “We didn’t like each other.” It wasn’t until 1999, at Mexico’s Todos Santos, that the two first towed each other into deadly swells. “Every time we went out,” says Gerlach, “it just felt natural.”

Big Moment: In 2001, Parsons won the XXL big-wave competition after Gerlach towed him into a 66-foot beast at Cortes Banks, 100 miles off San Diego. This year, Gerlach captured the 2006 XXL for a 68-footer Parsons slung him into at Todos Santos last December.

Role Play: “Mike is the captain,” says L.A.-based Gerlach, 40. “He’s the one with the jet ski who searches the Internet for swells. I just show up.” “Brad is a better surfer,” offers 41-year-old Parsons, who lives in San Clemente. “And he brings the food.”

What Doesn’t Kill You: “Brad towed me into a 50-footer at Jaws in 2005, then someone got in his way, so he couldn’t pick me up. I got blasted into the rocks. I was furious.” Says Gerlach, “I told that story at his wedding.”

тАФH. Thayer Walker

Brian Cousins and Steve Sullivan

President and Global Brand Vice President, Cloudveil

Cousins and Sullivan met in the early 1990s, hawking nordic wares on the retail floor of Jackson Hole, Wyoming’s Skinny Skis. Over alternately caffeinated (at work) and beery (after work) brainstorming sessions, they dreamed up “a new brand with an authentic mountain-town image geared to the backcountry athlete,” says Cousins, 34. Three years later, in 1997, the two borrowed from family and friends to launch CloudveilтАФnamed after a peak in the Tetons.

Big Moment: Choosing breathable, weather-resistantтАФand underutilizedтАФSchoeller fabrics to produce the Serendipity, the industry’s first soft-shell jacket. The piece led them to $1 million in sales by 2000.

Role Play: “Steve’s foot is fully on the gas, while I have the steering wheel and the brake,” says Cousins. “When he speaks, it’s walk softly, carry a big stick,” says Sullivan. “I just swing the stick.”

Getting Twisted: “Most of the samples from our first spring line got sucked away in the tornado that hit the 1999 Outdoor Retailer show in Salt Lake City,” says Sullivan. “That was a real bonding moment.”

Up Next: Last year, they sold the company to Sport Brands International. Still running the show, the pair plan to open Cloudveil’s first store next year.

тАФKevin Kennedy