HOW DO YOU DESCRIBE IT—the smell of mammoth?

At first there’s nothing. You’re standing beside a beer cooler on the bank of a frozen Siberian river, and your nose is numb with cold. The picnic-size plastic cooler is full, not of beer, but of fur, thick brown tangles of it, like scraped-up remnants of week-old roadkill, clumped and clotted with gray mud. You reach in and grab a handful in your ski glove, hold it to your face, suck your breath in deep: the pure sting of Arctic air. Then come the first faint traces of the animal—warm, only slightly rank, ammoniacal, like a wet dog drying in the sun.

You kneel down over the cooler and lower your head inside, right above the shaggy mess of hair, which you see now isn’t just brown but also threaded with black, with red, with strands bleached gold by time. The next whiff knocks you back like a bong hit. It’s the hot reek of a walking, breathing, pissing, shitting beast, as real and as shocking as your first glimpse of the elephants on that preschool trip to the zoo—and these dead 23,000 years. And you think, How many living human beings have ever smelled this? And how many generations of the vanished dead?

That was also, for me, the moment I felt like I first understood Bernard Buigues.

WE’D MET NEARLY a year before and as far away from the tundra as I can imagine, in a bistro in Paris on New Year’s Eve day. I’d heard about him that fall, as many people had, when the story broke worldwide that the frozen, apparently had been unearthed by a team of French explorers in Siberia, that the carcass (under the bright glare of the Discovery Channel’s cameras) had been flown to a laboratory in an underground ice cave, and—here’s the part that really drove them wild, the TV reporters and scientific naysayers and millennial evangelists—that its discoverers hoped to clone it. I might as well admit: That’s what hooked me, too.

During a visit to Paris, I’d phoned Buigues, the head of the expedition, and he’d invited me to lunch at a corner restaurant not far from the Place de la Bastille, with worn tile floors and plate-glass windows and white paper tablecloths. Buigues is compact, bald, and supremely self-possessed, with the sort of easy charm that, when you first meet him, makes you intensely conscious of not being French. And—despite the Frankensteinish specters conjured up by such phrases as “underground Siberian cloning laboratory”—he isn’t a scientist at all, let alone a mad one. After spending half his life as a bohemian jack-of-all-trades, he took an improbable detour into polar exploration, becoming a kind of Arctic impresario, a Gore-Tex version of Jules Verne’s Passepartout.

Since 1992, Buigues told me, he’d been leading and organizing North Pole expeditions for scientists, film crews, and well-heeled tourists, using as his staging point an old Soviet outpost called Khatanga. (His permanent home is still just outside Paris with his wife, Sylvie, the general director of French clothing retailer Agnès B.’s European stores.) Buigues got to Siberia at just the right moment. With scientists, government delegations, and adventure tourists lining up to visit a region that had been closed off for nearly a century, his company—Cercles Polaires Expéditions, or Cerpolex—boomed. That was how Buigues heard about the mammoth, which had been discovered in the summer of 1997 by Dolgan nomads who spotted its tusks and furry hide poking out of the thawing permafrost. Buigues went out to the site one night at dusk and decided to excavate the enormous animal himself.

Since then the French explorer’s mammoth-hunt has been fueled by passion, not profits. Buigues says he spent more than $1.2 million of his Cerpolex earnings before the Discovery Channel—which knew a good thing when it saw one and had been quick to sign Buigues on an exclusive contract—stepped in last year to pick up the tab. (The cable network won’t divulge how many millions it’s spent since then.) Driven by a single-minded desire to resurrect the defunct beast he’d laid claim to, Buigues had recruited an international team of scientists and spent weeks in the fall of 1999 at the site, chipping away with pickaxes at the granite-hard permafrost. Buigues managed to carve out a 23-ton block containing the mammoth and fly it by helicopter back to Khatanga, and—voilà!—the thawing was almost ready to begin.

The entire operation was filmed by the Discovery Channel, and the resulting two-hour special, which aired three months after our Y2K luncheon, set a new record as the most-watched program in the network’s history. Its money shot was an unforgettable sequence of the block of permafrost rising up into the sunset-lit Siberian sky and soaring off toward Khatanga with two huge tusks protruding from one side. (Buigues, with his unflagging showman’s instinct, had fastened them there.)

In Paris, as we drained the bottle of burgundy that Buigues had ordered with our meal, he covered the paper tablecloth with sketches: a diagram of how they’d lifted the mammoth, a map of northern Siberia. “An incredible place,” he said. “It is a place that obliges one to think about time, about the measure of time. In Khatanga, the Russian people live as if it were 30, 40 years ago—still Soviet times. For the nomads living in the tundra, dressed in reindeer skins, time stopped 500 years ago. And then there is this mammoth, this frozen animal that brings you back thousands and thousands of years. You have to realize, it isn’t a fossil. It’s got hair and skin and meat. We found plants trapped under the body that were still green. It could have died a few days ago.”

���ϳԹ��� the restaurant, in the fading winter light, Parisians hurried past toward New Year’s Eve celebrations, carrying flowers and champagne. Buigues didn’t seem to notice, or to care. He was, I suspected, already far away from the rest of us, somewhere up ahead or perhaps behind, in a millennium of his own making.

THE NEXT TIME I LUNCHED with Bernard Buigues it was somewhat different: a couple of protein bars forced down amid the stink of kerosene aboard an old, soot-blackened Soviet-vintage Mi-8 helicopter. We were going mammoth-hunting.

We’d set out that morning from Khatanga, a town that I’d found bizarrely transformed by the presence of Buigues and his frozen beast. On a typical evening at its only restaurant and bar (called Restaurant Bar) you’d find a clientele that included TV producers from southern California, Dolgan tribesmen, suave Frenchmen drinking cognac toasts, and Russian mafiosi in black leather blazers, dancing stiffly with the mastodontic local prostitutes. (The bartender, meanwhile, would be watching television: a dubbed episode of Friends.)

Our group aboard the helicopter was almost as motley. Discovery Channel tech guys fussed with their expensive equipment like nannies with restless infants, while Buigues and another of the Frenchmen lolled back atop the reserve fuel tank, steeped in kerosene fumes, unconcernedly smoking Gitanes.

Below us in all directions stretched a howling desert of white, stubbled here and there with a few stunted larches leaning at crazy angles against the wind-borne snow. These miserable trees make up the most northerly forest in the world—and the spur of land they cling to, the Taimyr Peninsula, is the northernmost continental land on earth, riding high atop the hunched back of Mother Russia. It’s a place farther east than Bangkok, farther north than Barrow, Alaska, and by the time I arrived, in mid-October, deep winter had set in for more than a month. Peering through the helicopter’s porthole, I thought of Ice-Nine, the apocalyptic Cold War substance in Kurt Vonnegut’s novel Cat’s Cradle, one single drop of which is sufficient to freeze solid all the water on earth, forever.

But just as the Taimyr wilderness turns solid every September, in a single sudden shock, so too it thaws every June, abruptly, in a matter of just a few days. The barren ice fields become mosquito-ridden marshes, and the melting snow pours toward the Arctic Sea in streams and rivers that overflow their banks, cutting new channels through the hard substrata of frozen mud. This is when the mammoths come out. Not just mammoths, either, but other bizarre, antediluvian monsters: woolly rhinoceroses, giant elk, Pleistocene bison, all of which roamed these steppes until after the last Ice Age, 10,000 years ago—when all these shaggy beasts suddenly, mysteriously, died off.

The floods were what brought Buigues’s first mammoth to light. A Dolgan herdsman named Ganady Jarkov stumbled upon it near a riverbank as he drove his herd of reindeer toward fresh grazing. He removed the tusks, which he later bartered to Buigues for some coffee, tea, and gasoline.

Thanks to the infusion of cash from the Discovery Channel, Buigues relaunched his expedition on an even grander scale last summer. Not only did he prepare to defrost the Jarkov mammoth, he also sent scores of local operatives out looking for bones, tusks, and other remains. Buigues recruited various clans of Dolgan tribesmen (known as “brigades”), promising to reward them for any material brought back from their summer wanderings.

A few days before my arrival, word had come in through the grapevine to Buigues’s headquarters in Khatanga that the last of the Dolgan brigades was on its way back across the tundra, returning with a hefty load of bones and tusks. So we had gone out by helicopter to search for them, with nothing but the vaguest sense of possible rendezvous sites. The Taimyr Peninsula is almost the size of California, with an average of just one inhabitant every 13 square miles. It’s easy to lose yourself there.

BUIGUES HAD TOLD me that in Siberia he often felt like an 18th-century explorer, and now, on the helicopter, it was easy to see why, as our polyglot crew sailed over seas of snow aboard a smelly, cramped, fragile-seeming craft, scanning the horizon. The scrubby forest had given way to open tundra, illegible to my unaccustomed eyes. Were we flying a hundred feet above the ground, or a thousand? The landscape fractured into patterns of abstraction, vast matrices of polyhedrons and faceted surfaces of lakes, flecked with gray and white like hewn granite. Cresting a hill, we startled a herd of gray smudges that bolted away en masse across the snow. “Reindeer!” Buigues shouted above the engine’s din. Suddenly, Siberia seemed anything but barren: an icy Serengeti.

The tribesmen couldn’t be far off. Dolgans live on reindeer. They hunt reindeer, herd reindeer, eat reindeer meat, drink reindeer milk, ride on reindeer’s backs, drive reindeer-drawn sleighs, wear clothes and shoes made of reindeer skins. When a Dolgan man has to urinate, he goes out into the herd and pisses into the animals’ mouths, so that the reindeer will have a source of salt. Even the Dolgans’ houses are made of reindeer hides, stretched on wooden frameworks and mounted on sled runners—so that they can be pulled across the tundra, by reindeer. (On the Taimyr, I lived on reindeer, too, since this is what every meal at Restaurant Bar seemed to consist of. Over the course of a week, I sampled chopped reindeer, reindeer cutlets, reindeer entrecôte, reindeer with egg, reindeer without egg, reindeer sausage, and reindeer Stroganoff—all of it similarly gray and stringy.)

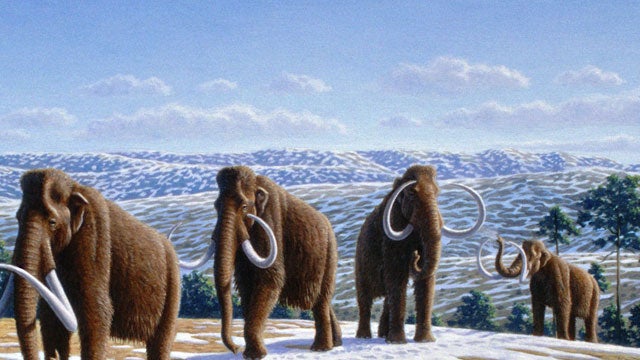

Twenty millennia ago, a helicopter flying across the Taimyr would have startled herds of mammoths. Prehistoric elephants—not just the woolly mammoths of Siberia, but others, such as American mastodons—were a common sight across the northern half of the globe. Most scientists think that, like their modern cousins, they must have been highly intelligent animals, gentle unless provoked. You wouldn’t have wanted to provoke a woolly mammoth without good reason—they stood up to 11 feet at the shoulder, with tusks as long as 13 feet. Prehistoric people hunted them for their meat and ivory, but they also seem to have observed them as carefully as human beings have ever observed an animal: From Siberia to Utah, they chipped their images onto cliff faces, scratched them onto flat rocks, and painted them on cave walls. Mammoths, one might guess, were in some ways the reindeer of Stone Age man.

One of the Dolgan reindeer-pulled mobile homes sat atop a low swell ahead of us, behind a feeble windbreak of dead branches. As our helicopter touched down, sending up a spray of snow, a tiny, Asiatic-looking man, hooded in white reindeer fur, came staggering out, a pair of huskies at his heels. Buigues jumped out, a Discovery Channel cameraman close at hand. He made a few inquiries in Russian, and then we were off again in search of the missing brigade. The herdsman, left behind in his barely post-Pleistocene surroundings, gave hardly an upward glance. Already, the Dolgans are used to the paleontologist- and cameraman-bearing helicopters that occasionally drop from the sky. As Buigues told me proudly, “They very quickly learned to perform for the cameras, to do as many takes as the producers wanted.” If you asked some of these Dolgans how they earn a living, they might honestly be able to say reindeer herding, ice fishing, and the Discovery Channel.

We never did find the lost brigade. We did, however, come across some mammoth remains, of a sort, that afternoon. We had stopped in the village of Novorybnoye, the Taimyr’s largest Dolgan settlement. As soon as we landed, we were surrounded by a crowd of people of all ages, dressed in an assortment of cold-weather gear: fur parkas, beaded-leather moccasin boots, cast-off Russian army pants, a hat with the Adidas logo. The ever-present huskies marked their territory on the helicopter’s landing gear.

An old woman pushed her way toward me through the crowd, muttering something to our interpreter: “She have something she want to sell you.” Reaching deep into some inner recess of her oversize down parka, she produced a knotted thong of greasy reindeer leather, on which were strung four chunky pieces of old ivory—mammoth ivory. The yellowing bars and rings were pierced with well-worn holes, and deeply notched in strange crosshatching patterns. They were bridle fittings, used by the Dolgans to adorn—what else?—their reindeer.

While carcasses like the Jarkov mammoth are very rare, the bones and tusks of long-dead mammoths are so plentiful on the Siberian tundra that the natives carve them into buttons, knife handles, and utensils of every sort. For centuries, they’ve sold the ivory to traders who’ve shipped it to far corners of the world. Every summer the ivory merchants come out to Siberia from Moscow and St. Petersburg, and each year Russia legally exports about five or six tons of mammoth ivory, which American craft suppliers sell for $20 to $150 a pound, depending on quality.

As for the Dolgans, whose world contains no living creature remotely resembling a mammoth, their traditional belief is that the bones belong to a species of giant burrowing mole that dies instantly on contact with the air or sunlight. Most of them now accept the official paleontological explanations. But even so, the mammoth remains for them a mysterious being, gifted with terrifying powers. When the Dolgans remove a skeleton’s tusks, they sacrifice a dog or a white reindeer, lest the animal’s vengeful spirit return from deep underground, seeking revenge.

THE MAMMOTH THAT rose from the dead in 1999, the reeking Pleistocene carcass that made television history, now rests in an ice-sheathed tunnel bored into the bank of the frozen Khatanga River. The block that Buigues’s team carved from the tundra was moved into the tunnel, where the temperature hovers steadily below zero, so that it may be slowly defrosted and studied without any of its tissues deteriorating—and in order to preserve its DNA.

Khatanga’s 5,000 inhabitants seem, as Buigues had hinted, stranded somewhere deep in the grim and endless Brezhnev years. I’d arrived there on an Antonov turboprop from Moscow in the middle of the night, along with a group of scientists and Discovery Channel people. When the plane taxied to a stop, the cabin door swung open, and in a blast of frigid air a Russian soldier in a heavy overcoat came stomping in. As he lifted his hand to salute us, I saw that the shiny red badge on his cap still bore the gold hammer and sickle of the Soviet Union. Up here, apparently, they hadn’t bothered to change. The town’s main streets are lined with ramshackle wooden buildings, spewing smokestacks, and sad low-rise apartments, and the shops along Sovietskaya Street have names like Store Number 6—where a middle-aged lady stands guard over a locked vitrine containing three plastic combs, a rubber hairbrush, and a single box of Q-Tips.

Buigues’s team hadn’t built the so-called ice cave. It was already there. Last year’s Discovery Channel special made much of the fact that it had been “constructed for unknown reasons during the Stalin era.” But when I asked the Taimyr’s regional governor, Nikolai Alexandrovich Fokhin, about this, he dismissed any hints of buried missile silos or secret torture chambers. “We built the cave about 15 years ago,” he said, “to store frozen fish and reindeer meat.” And in fact, when the television crews returned last fall, they found thousands of fish heaped up around the mammoth, stockpiled by locals less concerned with paleontology than with the kind of dead animals they could eat.

Despite the sanguine predictions of Buigues and the Discovery Channel, no one quite knew what was inside the block. True, there was hair and skin in some places on the outside, and a ground-penetrating radar scan had shown a large mass within it. But Ross MacPhee, a zoologist from the American Museum of Natural History whom Buigues had brought in to help with the defrosting, told me he suspected the permafrost contained little more than mud, rocks, and a few chopped-up bones, raising the discomfiting possibility that the Jarkov mammoth could become the Pleistocene version of the infamous live TV special during which Geraldo Rivera penetrated Al Capone’s “underground vault.” When I mentioned this analogy to one of the Discovery Channel producers, she blanched visibly.

The television crews had returned to get footage for a sequel, scheduled to air March 11, to “Raising the Mammoth,” their great success of the year before. No expense had been spared. The executive producer, a short, red-faced Washingtonian named Mick Kaczorowski, told me they’d even commissioned a full-scale, anatomically correct mammoth carcass made of polyurethane and yak hair. In the course of the program, this faux mammoth would be attacked by real wolves and vultures.

For the defrosting scenes, Buigues and the scientists, under gentle coaxing from Kaczorowski’s staff, were dressed up in shiny, Flash Gordonesque gray lab suits. (“I have no idea what this is for,” MacPhee sighed off-camera. Strapping and bearded, the very image of an old-school fossil hunter, he wasn’t exactly born to wear rayon.) The scientists’ equipment was nowhere near as impressive as their costumes. It consisted, more or less, of hair dryers. In early experiments, Buigues had discovered that this prosaic technology worked wonders in melting the permafrost just enough to allow it to be scraped away without unfreezing the flesh of the dead animal. And so a battery of gleaming, salon-model Wigo Taifun 1100s stood by, waiting to be aimed at the block.

Yet the mammoth didn’t actually have a lot of hair left. It had almost all been pulled out by local souvenir hunters last winter while the block sat outside the ice cave. Wherever they’d plucked the hair, they’d stuck in coins and ruble notes, as a gesture of appeasement toward the ancient beast, or perhaps toward the paleontologists. (A good deal of hair had been salvaged during the excavation, though, and was stored in the beer cooler I’d been shown. And enough genetic testing has been done to discern that the animal was a male.) The only thing mammoth-looking about the block—besides the tusks that Buigues had reattached—was that it was big, brown, and lumpy.

The cameras rolled, the hair dryers went full blast, and after a minute or so Buigues dramatically produced the first piece of mammoth flesh: a stringy scrap a few inches long, reddish and fibrous, like beef jerky. (He’d actually found it that afternoon, in an earlier defrosting session.) Nearby in the block, there were several protruding vertebrae and a broken rib. This wasn’t quite the perfect heat-n-serve mammoth that the Discovery Channel, its viewers, and even Buigues himself had expected—it was more like one that had been through a Cuisinart—but the scientists were nonetheless pleased. The scrap of flesh was the first intact soft tissue recovered from the carcass.

Kaczorowski, the producer, was stamping his feet with excitement and from the cold—after a couple of hours in the ice cave, his face had reddened until he looked somewhat like a peeled and parboiled monkey. “We’ll use the sound track of that Dolgan who was singing at Bernard’s house last night,” he told one of the other television people. “You’ll love it when it’s got a full orchestra behind it—it’ll be very dramatic, very Russian.”

AS DRAMATIC AS it may have been, the defrosting still didn’t bode well for the prospects of cloning—the lurking, thrilling idea that had drawn the huge television audiences (and me) in the first place. Since the heady first days after the mammoth’s helicopter flight, the prospect of a reborn race of woollies someday emerging from the ice cave has receded further and further into the distance.

Ever since the movie Jurassic Park and the 1996 birth of Dolly the sheep, the idea of has hovered around the collective consciousness of both Hollywood and science. A few years before Buigues arrived on the scene, a Japanese expedition came to the Taimyr to search (without success) for a specimen from which they might clone . Buigues and one of his scientific collaborators, a University of Northern Arizona paleontologist named Larry Agenbroad, originally hailed their specimen as a possible source of viable DNA—or even sperm—that would permit cloning. But almost immediately other scientists (including MacPhee, who hadn’t yet met Buigues) stepped forward to denounce the notion that a mammoth could ever be cloned—or that even if it could be, it ought to be.

The biggest practical difficulty, MacPhee says, is that DNA’s fragile strands deteriorate quickly, and no foreseeable technology can repair it. And besides, he adds, “Who’s going to want to have a herd of mammoths lumbering across the countryside? You’d end up with one or two animals cloned, as a kind of freak show, and then everyone would lose interest.”

Even so, the week I left for Khatanga, a New York Times headline announced the planned cloning of an extinct animal: not a mammoth, but a breed of Spanish mountain goat, the last of which had died a few months earlier. The scientists were given a good chance of success.

Agenbroad still believes that the Khatanga mammoth, despite its condition, may yet yield cloneable DNA. Moreover, he has few qualms about the prospect. “I live in the West, where we humans, the hunters and ranchers, eliminated huge numbers of grizzly bears and wolves. Now the federal government is bringing them back. Is that so different?” After Agenbroad spoke in favor of cloning on the Discovery Channel’s first broadcast, he received a barrage of hate e-mail. But he continues unapologetically to envision a not-too-distant future in which mammoths range like bison across the grasslands of Asia and North America—and points out that the director of Pleistocene Park, a nature reserve in Siberia, has announced that he’s ready to provide a loving home to a cloned mammoth, whenever the first one happens to be born.

If the birth of that 21st-century mammoth remains out of reach, solid information about the disappearance of the Pleistocene mammoths is equally elusive. By around 8,000 b.c. they were all gone, save a remnant population that held out for a few thousand years longer on a small Siberian island, living and dying while the pharaohs ruled Egypt. Scientists are sharply divided over what caused the extinction. Their three leading hypotheses, Agenbroad told me, can be summed up as “overkill, overchill, and overill.” The debate is about far more than paleontology. It’s about the past and future of humanity’s relationship with the natural world.

MacPhee is the illness theory’s leading proponent. It’s nearly impossible that humans hunted mammoths to extinction, he told me as we sat one morning in his room at Khatanga’s lone hotel, drinking cognac. “It contradicts everything we know about how extinctions happen,” he said. “Look at whales. For centuries you had enormous whale fleets armed with the most sophisticated technology of their time, manned by experts working morning, noon, and night to kill more whales. And of course they caused enormous destruction. But how many whale species have gone extinct in the past 500 years? Zero.” The most likely culprit for the mammoths’ demise, MacPhee believes, was some sort of global epidemic, a “hyperdisease” possibly borne by humans. This would explain why the animals vanished from the New World shortly after the ancestors of native Americans arrived.

Scientists of the “overchill” school believe that climate changes after the last Ice Age destroyed habitat and vegetation that the mammoths needed to survive. But the theory that most captures the public’s imagination is the overkill hypothesis. Agenbroad has spent decades excavating mammoth remains around the western United States. “You can’t work on a mammoth-kill site without getting the idea you’re looking at a magnificent animal that has been butchered by humans,” he says. “Eleven thousand years ago, man and mammoths were mixing it up, no doubt about it. Especially in America, where they’d never been hunted before and weren’t used to this funny-looking predator. It was like shooting ducks in a bathtub.” Agenbroad believes that a sudden burst in human population, along with wickedly efficient new tools such as improved spearpoints, drove mammoths over the brink.

In other words, humans were doing then exactly what their descendants, according to environmentalists, are doing now: overbreeding and trashing nature with technology. MacPhee scoffs at what he sees as the all-too-convenient sentimental appeal of this idea: “It fits with the worldview that everything wrong with the planet has to do with what humans have done.” Furthermore, he adds, the theory would be far less appealing if woolly mammoths didn’t make such cute, guilt-inducing victims: not just elephants, but shaggy, plush-toy versions of elephants—a species that could’ve been invented by Hasbro.

Still, Agenbroad takes his argument one step further. If the mammoth was one of the first species that human technology sent into oblivion, we can atone for it by making it one of the first species that human technology will resurrect. “We almost owe it to ’em,” he says.

ON OCTOBER DAYS in Khatanga, the Arctic sun floats lazily into view at midmorning and then drifts along the horizon like a half-inflated helium balloon until midafternoon. Dawn and dusk last for hours, saturating the entire snowy landscape with the deep blue and orange of the sky. Among the drifts rise half-finished buildings, piles of bricks, and rusted twists of metal, since nothing in Khatanga is ever torn down or hauled away, but simply left to stand in the place where it died or was forgotten. One vast section of town is the abandoned military base, with skeletons of jeeps and a plane’s fuselage abandoned at the roadside, and rows of collapsing barracks, slogans from Lenin hanging askew above their doorways.

Still, here and there I found nodes of buzzing activity. Intermittently for several days, a lime-green ultralight plane whirred back and forth above the airstrip—a French pilot testing out the latest gadget that Buigues had ordered from abroad. A couple of blocks away, an old wooden bank had been converted into a laboratory, where MacPhee and his colleagues drilled core samples from bones gathered over the summer.

But the center of all the action was a sprawling single-story house where Buigues held court like a tribal chieftain. (A random sampling of its clutter tells everything about him: a mammoth tusk, a pair of Sorel boots, a half-empty case of champagne.) When Buigues is in town, there is a constant stream of visitors and supplicants: television producers needing to schedule a shoot, Cerpolex employees planning expeditions, Dolgans selling mammoth bones or just stopping by for a glass of cognac.

In every superficial sense, the 46-year-old Buigues is an unlikely Arctic explorer. He spent his early childhood on the edge of the desert, in Morocco’s Atlas Mountains, on a farm settled by his grandfather. “Until I was seven, I never went to school,” he says. “I played outdoors with the Arab children, and my mother taught me at home.” Then, in 1962, amid the collapse of colonialism, his father moved the family back to France, to a small town near Toulouse. “On the first day of school, I was excited about this new thing, the books and the new clothes. I got there, sat and listened for a few hours, and decided I didn’t like it so much, so I stood up and told the teacher that I’d had enough school for the day and I was leaving. She told me to sit down. I remember how shocked I was that this was how it worked—that I’d lost my freedom.”

From that very first day, Buiges says, he plotted his escape. Finally, at 15, he ran away from home. Buiges moved in with an older friend, an artist, and—with plans of lending his support to the proletarian revolution—took a job in a plywood factory. Eventually he left and started university, but soon dropped out again. In his twenties he drifted from job to job: cook, ambulance driver, mechanic. Then, through the parents of a girlfriend, he happened to meet Jean-Louis Etienne, the French explorer who would later become famous for his ski expeditions across both poles. “He had just decided to make an expedition by ship to Greenland,” Buiges recalls, “and he told me, ‘I need somebody like you on board, someone who can do everything from cooking to fixing the engine.”

For the next decade, Buigues served as Etienne’s right-hand man. Shortly after the start of perestroika, he visited the Siberian Arctic for the first time and left Etienne to start Cerpolex. “Jean-Louis was mostly focused on the Antarctic,” he says. “But the Arctic has more magic for me. The North Pole is alive, with the ice always cracking and moving, and the tundra also always moves and changes, like a desert, like a white Sahara.”

Buigues says he also loves the far north because, unlike the far south, it’s alive with humanity. In fact, he is one of the few outsiders whom the nomads trust, according to Vladimir Eisner, one of his longtime confidantes in Khatanga. “Their life has been hard since Communism ended,” he told me. “Bernard gives them flour, tea, sugar, petrol, clothes for their children. And when he pays them money, he gives it not to the men, who will drink it away, but to their wives, who will feed the family.”

The forlorn environs of far northern Siberia are a kind of paradise for Buigues, one of the few places on earth where it is truly possible to slip the bonds of the present.(He revels in his double existence, in coming home after months, bearded and smelly, to his wife in Paris.) In Soviet times, too, despite the region’s reputation as a place of imprisonment, it was also a place where some Russians came seeking freedom. In Khatanga, Buigues has surrounded himself with men like these—frost-seasoned outdoorsmen like Eisner and Boris Lebedev, a hulking, gentle-eyed trapper who came to town in the 1970s. “I still remember my first sight of it,” Lebedev says, “a little village in those days, with smoke rising from the roofs of the houses. It was only here in the north that a human being could be himself.” Buigues’s reasons for coming, perhaps, are not so very different.

The French interloper’s presence in town has won him enemies as well as friends; recently, he told me, he got word that Moscow ivory dealers were irritated by his competition for mammoth tusks and might be planning some sort of reprisal. But he’ll continue his hunt, he says, even though he’s not exactly sure why, not certain what has brought him from a farmhouse in the African hills to a village at the edge of the polar sea. Perhaps, he says, what’s drawn him to mammoths is some half-lost ancestral memory of them, “a knowledge that we have all kept deep in our cortex. You know, in Paris I live near the zoo, and I often go there to see the children watching the elephants, standing there and looking, much longer than they look at the lions, or the bears, or the giraffes. Maybe this has something to do with it also.”

EVEN IF BUIGUES’S first mammoth didn’t, as the world expected, turn out to be a perfect specimen, ready to blink its eyes and reawaken, there are almost certainly others waiting, still asleep under the tundra.

In August 1900 a Yakut tribesman hunting elk along the Berezovka River, in far eastern Siberia, came upon the head and forelimbs of a monstrous creature—its nose the length of a year-old reindeer calf—protruding from the bank. Word eventually made its way to the czarist authorities, and the following summer an official expedition arrived at the site, after a four-month journey via Trans-Siberian Express, boat, sleigh, and horseback. (One scientist recalled eating reindeer meat, buying mammoth-ivory trinkets, and seeing people still dressed “in the style of the ‘eighties.'” Different eighties, otherwise a familiar story.)

The explorers found the carcass in a remarkable state of preservation—nearly intact except for its head. In fact, the mammoth’s flesh was so succulent-looking that they were tempted to eat some, though its awful stench deterred them. The expedition’s sled dogs, however, dived in with gusto. The scientists carefully recorded their find and photographed it. (One memorable image shows a local tribesman posing proudly beside the mammoth’s genitalia. The unfortunate animal seems to have died in a state of some excitement—its penis was fully three feet long.) They cut the carcass into pieces, loaded it onto dogsleds, and finally got it back to St. Petersburg to show the czar and czarina. Nicholas inspected the mammoth with interest; Alexandra pressed her handkerchief to her nose and asked to be taken “as far away from this as possible.”

The Berezovka mammoth—still on display, no longer pungent, in St. Petersburg—was, until Bernard Buigues and the Discovery Channel came along, the most famous mammoth ever found. Other fairly well preserved examples have turned up now and then, too, always by chance. But even in recent years, when Soviet scientists excavated such finds, they stripped away the permafrost with jets of hot water and preserved the mammoths with chemicals like paraffin—both of which irreparably damaged the specimens.

There’s every reason to think that more mammoths wait to be found—perhaps even hundreds more. “I don’t think the one we’ve got in the ice cave now will ever pan out to be very much,” MacPhee says. “But I have every expectation that Bernard’s eventually going to turn up the kind of mammoth he’s looking for. No one’s ever staged a search like what he’s doing, systematically, on such a scale.”

Last summer, in only a few weeks, Buigues’s oddly matched team of Dolgans, scientists, and Russian fishermen found so many mammoth tusks and bones that the collection, stored in the former bank in Khatanga, now rivals those assembled over centuries by the world’s great museums. And he plans to continue the hunt—at least for the time being, he told me, until the restlessness that brought him to the Arctic draws him into something new. (“You see,” he told me, “I’ve also got a plan for another kind of Arctic expedition, a truly incredible adventure, you aren’t allowed to publish anything about this…”)

For now, Buigues is firmly in the grip of his current obsession. His motives seem to have little to do with science, let alone entertainment. “Make no mistake,” says MacPhee, “he’s dreaming about that perfect mammoth. If not a cloned one, at least one that’s sealed up perfectly in the permafrost.” And until he finds his perfect mammoth, it’s not things like laboratory results or television ratings that keep him going. It’s a chunk of bone on the tundra, an ivory trinket in a Dolgan’s cupped hand, a whiff of mammoth on the cold Siberian air.

BESIDE THE FROZEN sheet of Lake Taimyr, I stood with Buigues as he knelt on the bank, freeing something from the drifted snow.

I’d taken off by helicopter from Khatanga again, two hours before—this time to pick up Buigues and his team, who were camped on the tundra on a hunt for new specimens. The Arctic sky was unusually clear that morning, and in the course of the flight my eyes had begun to grow accustomed to the glaring desert beneath us. I saw now that the unrelieved white of the landscape was actually the blue of buried water, the rose of reflected dawn, and the yellowish green of marsh grasses mounded beneath the drifts, awaiting spring.

We’d circled once before landing, watching the expedition members emerge, waving, from their tents. The wind was whipping off the lake’s huge surface, and they began striking camp even before we landed, eager to get aboard the helicopter. Buigues wasn’t among them. He was already down at the lakeside, waiting to show us his find. Here, last August, a Russian park ranger fishing in the shallows had hooked something unusual: a tuft of reddish-brown hair. Buigues suspected that it might be the rest of a partial mammoth that had been found eroding from the adjacent bank a decade or so earlier.

Struggling through the blistering wind toward the lake was like negotiating the surface of a hostile planet. As I made my way over the hummocky crest above the ice, I saw that the waters had receded before they’d frozen, exposing a dozen or so yards of bare lake bottom. Protruding from the frozen earth, like dinosaur fossils in a matrix of rock, was a row of brown vertebrae, ancient and massive. Only this wasn’t rock, and this was no fossil: All around it, like strands of fine, dead grass, long hairs sprouted from the snow. Buigues was crouched there, riding atop the buried animal’s back, imagining the living contours beneath him.

Adam Goodheart’s feature on the Philmont Boy Scout Ranch appeared in the November 1999 issue of ���ϳԹ���.