LANCE ARMSTRONG squirmed once. There s a photo.

Lance Armstrong

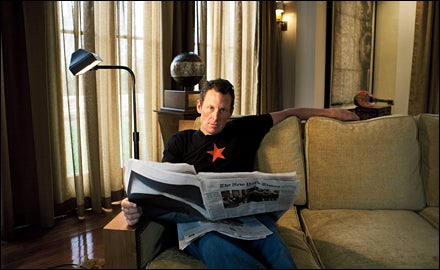

Armstrong at home in Aspen

Armstrong at home in AspenArmstrong at home in Aspen

Armstrong at home in Aspen

Armstrong at home in AspenArmstrong at home in Aspen

Armstrong at home in Aspen

Armstrong at home in AspenLance Armstrong

Armstrong at home in Aspen

Armstrong at home in AspenArmstrong at home in Aspen

Armstrong at home in Aspen

Armstrong at home in AspenIt wasn t one of his press-conference, get-me-away-from-these-dickheads-and-their-Floyd-Landis-questions squirms. That s bristling. Armstrong does that all the time. Like a couple of years ago, when I was interviewing him for this magazine and he brought up ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═° s July 2006 issue. The cover showed Floyd Landis staring out, next to the line Lance who?

Oh, you know,” Armstrong said, just the guy who won seven Tours de France. Whatever, man.”

I squirmed.

That s something Armstrong does well: make other people uncomfortable. Even he refers to it as the look.” It s how he controls the conversation, his bright light in the interrogation room. Someone gets out of line a rival, a teammate, a journalist and the emotion drops from his face. It s one of the fiercest stares ever. (Pity his kids when they start missing curfews.) He flattens his mouth, sets his jaw, looks straight ahead, and waits.

He waits for you to think about who he is, about the money and fame. He waits for you to think about the cancer and the yellow jerseys. Then he waits a little longer, for you to come to terms with the one advantage he has that makes everything else possible: Take it all away and he could still kick your ass.

But what if he couldn t? What if you were Alberto Contador?

Yes, Armstrong took third at the 2009 Tour de France. Yes, that would be a career-making result for many, even for a rider who wasn t returning from a four-year layoff and pushing 40. But Armstrong wanted more. He admits it. His racing showed it. He threw everything he had at Contador, dividing their team in the process. (They were, ostensibly, teammates.) Contador absorbed it all and still kicked his ass on the bike.

The victory was the Spaniard s fourth-straight in one of the three-week grand tours. He d won the Tour de France in 2007 and the Giro d Italia and Vuelta a Espa├▒a in 2008, making him one of only five riders ever to have won all three. (Lance isn t among them.) He didn t do it over the span of a career, either; he did it in 14 months. If not for the cycling politics that kept his team out of the 2008 Tour de France, Contador would likely be going for his fourth-straight Tour victory this July, at 27 the same age Armstrong was when he won his first.

Cycling has a term for the boss of the peloton, the one rider to whom all others defer: the patr├│n. There are times without a patr├│n, anarchic years when it seems that each new race brings a different winner and challengers. To be the patr├│n, a rider has to win the biggest races consistently and also have the force of personality to bend others to his will. By his third Tour victory, Armstrong was undeniably the patr├│n. He remained so until his retirement, which introduced a power vacuum that included the disastrous 2006 Tour of Floyd Landis, when Landis won the race but was later disqualified for failing a drug test.

This past October in Paris, at the gala presentation of the 2010 Tour de France route, the new patr├│n approached a seated and unprepared Armstrong and extended his hand. The photo of the moment could not be more telling. Contador, smirking, reaches down to shake hands with Lance, who s pinned awkwardly in his seat by Contador s positioning and not even making eye contact. The look” is nowhere to be seen.

The resulting photograph might be the only one in existence of someone making Lance Armstrong squirm. It also raises the question: Why is he back for more?

Read the full story in digital format here [coming soon].

LANCE ARMSTRONG squirmed once. There’s a photo.

It wasn’t one of his press-conference, get-me-away-from-these-dickheads-and-their-Floyd-Landis-questions squirms. That’s bristling. Armstrong does that all the time. Like a couple of years ago, when I was interviewing him for this magazine and he brought up ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═°‘s July 2006 issue. The cover showed Floyd Landis staring out, next to the line Lance who?

“”Oh, you know,”” Armstrong said, “”just the guy who won seven Tours de France. Whatever, man.””

I squirmed.

╠ř

That’s something Armstrong does well: make other people uncomfortable. Even he refers to it as “”the look.”” It’s how he controls the conversation, his bright light in the interrogation room. Someone gets out of lineÔÇöa rival, a teammate, a journalistÔÇöand the emotion drops from his face. It’s one of the fiercest stares ever. (Pity his kids when they start missing curfews.) He flattens his mouth, sets his jaw, looks straight ahead, and waits.

He waits for you to think about who he is, about the money and fame. He waits for you to think about the cancer and the yellow jerseys. Then he waits a little longer, for you to come to terms with the one advantage he has that makes everything else possible: Take it all away and he could still kick your ass.

But what if he couldn’t? What if you were Alberto Contador?

╠ř

Yes, Armstrong took third at the 2009 Tour de France. Yes, that would be a career-making result for many, even for a rider who wasn’t returning from a four-year layoff and pushing 40. But Armstrong wanted more. He admits it. His racing showed it. He threw everything he had at Contador, dividing their team in the process. (They were, ostensibly, teammates.) Contador absorbed it all and still kicked his ass on the bike.

The victory was the Spaniard’s fourth-straight in one of the three-week grand tours. He’d won the Tour de France in 2007 and the Giro d’Italia and Vuelta a Espa├▒a in 2008, making him one of only five riders ever to have won all three. (Lance isn’t among them.) He didn’t do it over the span of a career, either; he did it in 14 months. If not for the cycling politics that kept his team out of the 2008 Tour de France, Contador would likely be going for his fourth-straight Tour victory this July, at 27ÔÇöthe same age Armstrong was when he won his first.

Cycling has a term for the boss of the peloton, the one rider to whom all others defer: the patr├│n. There are times without a patr├│n, anarchic years when it seems that each new race brings a different winner and challengers. To be the patr├│n, a rider has to win the biggest races consistently and also have the force of personality to bend others to his will. By his third Tour victory, Armstrong was undeniably the patr├│n. He remained so until his retirement, which introduced a power vacuum that included the disastrous 2006 Tour of Floyd Landis, when Landis won the race but was later disqualified for failing a drug test.

This past October in Paris, at the gala presentation of the 2010 Tour de France route, the new patr├│n approached a seated and unprepared Armstrong and extended his hand. The photo of the moment could not be more telling. Contador, smirking, reaches down to shake hands with Lance, who’s pinned awkwardly in his seat by Contador’s positioning and not even making eye contact. “”The look”” is nowhere to be seen.

The resulting photograph might be the only one in existence of someone making Lance Armstrong squirm. It also raises the question: Why is he back for more?

EVEN IF ALBERTO CONTADOR weren’t the toughest opponent Armstrong has encountered in the Tour de France, even if Floyd Landis had never opened his mouth about dopingÔÇöand everything in Armstrong’s increasingly hectic, child-filled, obligation-bloated life were as simple as it was a decade agoÔÇöhe’d still be turning 39 in September.

The oldest man ever to win the Tour, Belgian Firmin Lambot, was 36 when he won in 1922. The average age of the top riders over the past 50 years has been 27, and the oldest champion during that period was Armstrong himself, when he won in 2005 at 33 years and ten months. As his podium finish last year showed, he’s still one of cycling’s best, but he hasn’t yet exhibited his previous form. In the middle of a fight to defend himself against the most damning drug allegations of his long careerÔÇöLandis’s claims that he and Armstrong doped while racing together between 2002 and 2006ÔÇöhe still has to find a way to train, perhaps harder than he ever has. He’ll have to figure out which of his 2009 shortcomings were due to rust from his four years off, which can be addressed with more time on the bike, and which he’ll have to accept as the irreversible ravages of age.

“I don’t know,” says Armstrong’s longtime coach, Chris Carmichael. “We didn’t get there last year, but we weren’t far off. One change I have noticed: He’s always adapted very quicklyÔÇötwo or three days of training and he can see a 10 percent increase, just massive adaptation; but now things will be going well, he’ll have some really good training days, then he’ll travel, miss a few days, and he doesn’t seem to hold his form as well as he used to. The gains are lost. That’s kind of anecdotal, but it’s my sense from what I’ve seen, and it’s one thing I haven’t seen with him before.”

If missed days and travel have become more of an issue than in the past, it didn’t seem to concern Armstrong through the early part of this year. He raced in Australia in January, flew to Hawaii for two separate winter training camps, pulled out of scheduled early-season races, chose a week of training and a one-day pro-am race in South Africa instead of the major ParisÔÇôNice stage race, and ended his spring campaign in Europe in mid-April, two weeks ahead of schedule.

“It’s over, let’s just say that,” Armstrong says of his globetrotting. “No more long trips to Africa. It’s time to bump it up a bit.” We’re in his hotel room in Bruges, Belgium, the day after April’s one-day Tour of Flanders, where he finished 27th, and two days before he’ll pull out of France’s Circuit de la Sarthe with an intestinal bug and return to the United States. A month later, on the same day Floyd Landis drops his bombshell, he’ll crash out of the Tour of California.

“Certainly I think we would have liked to have seen things turn out a different way,” says RadioShack team physiologist Allen Lim, a highly regarded sport scientist whom Armstrong lured away from the American Garmin-Transitions team in the off-season. “You can’t control everything. That’s what makes this whole sport and endeavor so exciting. But as our luck goes one way, so might our competitors’. It’s fully open. And I think by the time July comes around, no one will ever think about what happened in March. They’re going to be thinking about what’s happening in July.”

Armstrong’s biggest challenge for July will be regaining what he and his handlers call “the top end,” that superhuman level that allowed Contador to drop the rest of the contenders during the final few minutes of the Tour’s mountain stages. Developing this power involves targeted workouts, called VO2 drills, that tinker with the body’s ability to deliver oxygen by repeatedly stressing the system. Armstrong says he didn’t do enough of that work last season, something he blames partly on his training approach and partly on external circumstances like a broken collarbone, which interrupted his spring, and the birth of his fourth child last June.

“It was a mix of a lot of things,” Armstrong tells me, just three weeks before announcing that his fifth childÔÇöhis second with girlfriend Anna HansenÔÇöis due in October 2010. “It was being away for four years and never stressing that system. It was also a factor of not training that system when I did come back. The year was unique, in that it started in Australia, then the crash, and then a rush to get ready for the Giro. Then you just suffer through the Giro. June was not a normal June for meÔÇönot racing, staying at home, having another baby. It was a hectic three or four months there.

“But I’ve got no regrets. Man, I had a good time last year. When you’re having a baby in Colorado, I wasn’t going to be anywhere else.

“We’ll change it this time,” he vows.

ARMSTRONG’S 2010 TOUR RUN started in the middle of 2009. Three days before the peloton rolled into Paris last July, when it had long since become clear that Contador would win, Armstrong announced that he would be leaving Astana to form a new team, sponsored by RadioShack. He would be taking team director Johan Bruyneel, the Belgian mastermind who had guided him to all seven of his Tour wins, plus as many Astana riders and staff as he couldÔÇöincluding, as it turned out, every member of the team’s Tour squad except Contador.

Contador had been nurtured by Bruyneel since his breakout 2007 season. He should have been able to count on the complete support of his team, if not until the end of the season then at least until the end of the race. Why not wait until after the Tour to make that announcement? Psychology. The timing meant Contador would be finishing the Tour surrounded by teammates and a director who he knew had not only decided to leave him but would be racing against him in 12 months.

“Contador knows Bruyneel is a great tactician,” says cycling analyst Phil Liggett. “And there’s no [team director] at Astana who’s going to guide him like that, I don’t think. So we’re going to see how clever he is now. Because Lance knows how he thinks. He knows he can’t beat Contador one on oneÔÇöthe strength is not there anymoreÔÇöbut he does know he can outthink him.”

At RadioShack’s first training campÔÇöheld in December, in Tucson, ArizonaÔÇöArmstrong continued the head games. “Last year we had the strongest team in the race,” he said. “Eight of those nine guys are on Radio┬şShack.”

In cycling, groups or individuals own the teamsÔÇöthe racing license and business structure. Sponsors provide the name and the funding. The Discovery Channel team that helped Contador win the 2007 TourÔÇöand which Armstrong used to win his seventhÔÇöwas the same entity as the U.S. Postal Service team that helped Armstrong win his first six. When Discovery’s sponsorship ran out at the end of 2007, Bruyneel planned to retire. But Astana, a team backed by a consortium of Kazakh sponsors, wanted a new start after a summer of drug scandals. Bruyneel, who’s also been named in the Landis allegations, accepted an offer to rebuild the team and brought along several core employees and riders from the Postal/Discovery juggernaut, including Contador and Armstrong.

In the 11 years between Armstrong’s first Tour win, in 1999, and the 2009 Tour, Bruy┬şneel teams won nine of the ten Tours de France they were allowed to enter, plus two Giros and two Vueltas. That’s the organization Contador had behind him for the past three seasons, and the organization that is now lined up against him.

“The conflict last year was a personality conflict,” Armstrong said in Tucson. “Not that mine is good or bad. But this was very different. The proof is in the pudding. Eight of the nine [riders] are here now. That’s a testament to our program and Johan.”

Think about that. When in the history of professional sports has virtually an entire teamÔÇöfrom staff to athletesÔÇöwalked away from the best player in the game to regroup around an aging veteran who hadn’t won in more than four years? Imagine Shaquille O’Neal getting the Cavaliers to abandon LeBron James. Wouldn’t happen. But at Astana, it didÔÇöeven after Contador, in 2008, became the fifth rider in history to win all three grand tours and, in 2009, the first to win a Tour de France that Lance Armstrong wanted to win.

“Each year you get more experience,” Contador told me at Astana’s team training camp in January. “But the last year was probably equal to two or three normal years, in terms of learning. It helps me.”

Despite Armstrong’s and Bruyneel’s best efforts, Contador will still have a solid team at the Tour. Astana headed into last winter with only two notable riders under contract, Contador and Kazakhstan’s Alexander Vino┬şkourov, 36, a founding member of the team and former Tour podium finisher who returned late last season from a two-year doping suspension. But in December, by which time most quality riders have already signed contracts, Astana convinced Oscar Pereiro, the declared winner of the 2006 Tour after Landis’s disgrace, to delay retirement and also recruited Spaniard David de la Fuente and Italian Paolo Tiralongo, two gifted climbers who should be able to help Contador in the mountains. Though not as deep as Radio┬şShack, Astana won’t be the shell of a team it appeared to be at the end of 2009.

“They’ll be a little bit surprised that Astana has not imploded,” Phil Liggett says of Armstrong and Bruyneel. “It’s a very good team. That might have shocked RadioShack, that this is a team to be reckoned with, even though they ripped the heart out of it.”

“LOOK, ALBERTO IS a tough son of a bitch,” says Chris Carmichael. “When you push him, he pushes back.”

During a minor stage race in May 2004, Contador went into convulsions on the bike and crashed, unconscious, on the side of the road. Tests revealed a knot of abnormal, swollen blood vessels, called a cerebral cavernoma, that had begun bleeding into his brain. He has a visible scar running across the top of his scalp, from ear to ear, where neurosurgeons went in to repair the damage.

Nine months later, he won a stage of the 2005 Tour Down Under, his first race since his crash. “For me this win was the most important of my life, more than the Tour de France,” Contador said at the Astana camp in Spain. “Just because of everything I’d gone through in the hospital just before.”

He collected increasingly more prestigious wins over the next two seasons but missed out on his Tour debut in 2006 when a drug scandal left his team without enough riders to start the race. In 2007, he signed with Discovery and won the Tour in his first attempt. When his next team, Astana, was left out of that race in 2008, he answered by winning the Giro and the Vuelta. When Armstrong snuck away during an early stage of last year’s Tour, nearly grabbing yellow, Contador retaliated, ignoring team orders and dropping Armstrong with an attack on the first mountain stage.

“Contador was not a team man; there’s no doubt about that,” says Liggett. “If he had played his cards completely fairly and squarely, he’d have still gotten the first step on the podium. But that wasn’t what he was interested in. So he’s got a different season now.”

He started it aggressively.

“There are a lot of riders in the peloton who have to be respected,” Contador said in Spain. “There are always rivals. It’s always difficult to win. It doesn’t matter who’s in what race.” If anyone scares him, he says, it’s Luxembourg’s Andy Schleck, who finished second last year. It’s a telling point: Even though there’s a seven-time Tour winner gunning for him, Contador’s response is that there are other people who concern him more.

Whether or not Armstrong presents a major threat in Contador’s eyes, he certainly offers a tempting target. Two months after his guerrilla handshake attack last October, Contador got in another dig when he signed a sponsorship deal with Specialized. This was no accident. Specialized’s fiercest rival is fellow American brand Trek, which happens to be Armstrong’s longtime sponsor. If Armstrong vs. Contador and RadioShack vs. Astana weren’t drama enough, the Tour now has the world’s two biggest bike brands fighting a proxy war via cycling’s two biggest stars.

“It’s definitely real,” Armstrong says of their rivalry. “The realest I’ve ever felt. And I’m on the opposite end of it now. In the past, a lot of [my rivalries] were kind of manufactured, and I had the upper hand. This one’s not manufactured, and I have the low stack.

“Just from a power perspective, where we are in our careers. Alberto’s at the top of his game and probably going to get better. And I’m certainly not going to get any better. I might get better than I was last year, but I won’t get better than I was ten years ago. So that’s a little challenging.”

The early part of this season has offered Armstrong little solace. Cycling fans know not to read too much into spring races; individual riders have different goals, training methods, and strategies for starting the year. All that matters is July. Still, through April, Contador had entered four stage races and won three. During the same stretch, Armstrong finished 25th in Australia’s Tour Down Under, seventh in Spain’s five-stage Vuelta a Murcia, and 47th in the two-day, three-stage Criterium InternationalÔÇöhis first head-to-head showdown with Contador, who finished four minutes ahead, in 15th.

“I felt good in Australia but suffered in Murcia,” Armstrong says. “But I haven’t raced that much. This year in ParisÔÇôNice, those guys were apparently racing gutter to gutter all day, every day, in bad weatherÔÇöwindy, really intense, huge average watts. Just all-day, epic training. We didn’t get that in Murcia.”

He doesn’t mention who won ParisÔÇôNice. Doesn’t have to. Everyone knows Contador crushed it.

“WE HAVE TO BE REALISTIC about the fact that the race favorite is not on our team,” Bruyneel said in Tucson. “For us to have a chance to beat that favorite, we’ll probably have to adopt different strategies and have different cards to play.

“But Lance has won the Tour seven times, and he was third this yearÔÇölittle detail.”

It’s an important one to keep in mind. Elite riders at the peaks of their careers struggle to break the top ten. Armstrong returned from a four-year layoff and still made the podium.

“It was one of the great performances in sport,” Liggett says. “But because Lance is in a sport not everyone understands, nobody really appreciated the enormity of it.

“I think he expected too much of himself. But Lance does that. He’s not going to waste anybody’s time, least of all his own. He went into that race really believing he could win.”

That’s why Armstrong is back for more. Because he took four years off, broke his collarbone in March, went home for the birth of his fourth kid in June, and still came tantalizingly close in July; because he’s reassembled the strongest team in cycling; because he really, sincerely, with all his outsize Texas attitude, dislikes Contador; and because he honestly believes he can win again.

“I’m a realist and an optimist,” Armstrong says. “Realistically, this is very difficult. Alberto’s complete, he’s young, he’s explosive. You can go on and on. But at the same time I can sit back and go, ÔÇśShit, I’m optimistic, too.’ I can address it in the training. The team can play a part. I can look at the course and go, ÔÇśOK, seven sections of cobblestones on Stage 3: That’s a plus.’ Who’s going to make it through that? I think it will be a decisive day.”

Thus his trip to Belgium. Stage 3 of this year’s Tour will include several long, rough stretches of cobbles. Crashes and equipment failures are almost a given on these paths, which can become so narrow they string the riders out in single file. Time losses in the mayhem can be significant.

Armstrong may have lost a step, but he can still read a race better than anyone in cycling, and he’ll have the sport’s preeminent tactician calling the shots from the team car. They’ll know where the turns are, which direction the winds are blowing, how to drown out the cacophony of shifting gears and whining chains and hear the one off-key shift that signals that the race is about to be blown apart. When that happens, Armstrong will always be in the right place.

About 20 miles before the end of last year’s third stage, the route made a sharp turn that would leave the riders battling strong crosswinds to the finish. Armstrong sensed a battle brewing between two other teams in the race. As the peloton approached the turn, the riders from one of those teams began to assemble at the front. Armstrong knew something was going to happen. When the riders attacked out of the turn, he was in position to tag along while the peloton shattered behind them and huge gaps opened up.

Armstrong shot up to third overall and, more important, ended the day as the highest-placed rider on Astana, 19 seconds ahead of Contador. Astana’s victory in the team time trial the next day left him just 0.21 seconds out of the overall race lead.

Had Armstrong grabbed the yellow jersey that day, cycling tradition would have dictated that his teammates, including Contador, ride in his defense, which might have been enough to keep Armstrong in yellow all the way to Paris. For Contador to attack his teammate in the mountains a few days later would have been a huge breach of protocol if it had meant that he’d be attacking his own teammate in yellow. Just 0.21 seconds and everything could have changed.

“I thought I’d get it,” Armstrong says. “I always go in optimistic. I’m always half full, even last summer. Nobody else expected it, but, yeah, I thought I’d win the Tour. I was wrong, but that’s what I thought.”