ON FEBRUARY 13, an amateur Belgian cyclist named Johan Sermon slipped into bed early, hoping to rest up for an eight-hour training ride the next morning. A 21-year-old with strong prospects for a professional career, Sermon had undergone a complete cardiac evaluation a few days earlier, and doctors for his team, Daikin, had deemed him to be in excellent health. But shortly after dawn, Sermon’s mother found him lifeless in his bed. An autopsy listed the cause as heart failure—an astonishing exit for a young athlete in peak condition.

Tour de france drug testing

Sermon’s death was soon overshadowed by the demise of 34-year-old Marco “the Pirate” Pantani, the great Italian cyclist and 1998 Tour de France champion, whose career had been destroyed by doping allegations. Just hours after Sermon died, Pantani’s body was discovered in a hotel room in Rimini, Italy. A cocaine overdose became the grim final act of a storied career that was pockmarked with drug use, race expulsions, and controversy.

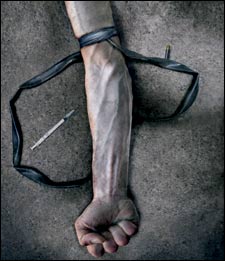

These deaths weren’t isolated occurrences. In the past 16 months, six other riders have died under circumstances eerily similar to Sermon’s. (See “The Fatal Finish Line,” below.) Looking for an explanation for this shocking death toll, cycling journalists were quick to raise a familiar chorus: Doping remained endemic to the peloton, and, whether directly or indirectly, it was taking lives. Writing in a London newspaper, Phil Liggett, the veteran cycling broadcaster, pointed out that as many as 100 international racers have died prematurely during the past decade, most from heart attacks. The likely cause, Liggett argued, was the ongoing abuse of EPO, a synthetic and stealthy version of a hormone that spurs red-blood-cell production and thus boosts endurance.

“A body of literature shows that EPO conveys a five- to 15-percent advantage,” says Charles Yesalis, an epidemiologist at Penn State University and an expert on drugs in sports. Translated into minutes, a five-percent boost would have been the difference between first and 143rd in last year’s Tour. But EPO can also be lethal. The drug’s most immediate threat is “hyperviscosity,” or thickened blood, which can cause a heart attack. Studies about permanent health effects from EPO use are inconclusive, but the sludge-like blood can linger for up to 120 days.

UNFORTUNATELY, AUTOPSIES can only show that a heart attack occurred, not that EPO caused it or was even present in the bloodstream at the time of death. Thus cycling remains where it’s been for decades: under a cloud, with little proof about who’s cheating, who isn’t, and what the fallout may be for the long-term health of riders.

If that conundrum sounds familiar, it should. Cycling endured a drug-related mega-scandal back in 1998, when the entire Festina team was kicked out of the Tour de France after an employee was busted with a carload of EPO and other banned substances. No knowledgeable observer thinks the sport has completely cleaned up since then.

“There are just as many cyclists using drugs now as ever before,” insists Yesalis. “Do I know enough to prove they’re cheating in a court of law? No. But I don’t believe you can win the Tour de France clean.”

In the United States, the deaths of Pantani and Sermon didn’t get much play, but other drug scandals have. Major League Baseball is grappling with an ongoing grand-jury investigation into BALCO, a San Francisco–area sports lab accused of providing steroids and human growth hormone to track athletes and pro baseball players, including superstars Barry Bonds and Jason Giambi. The heatstroke that in 2003 killed Baltimore Orioles pitcher Steve Bechler, 23, was linked to his use of the diet pill ephedra. In March, track cyclist Adham Sbeih, 30, an Olympic hopeful from Sacramento, California, received the first suspension ever issued to a U.S. athlete for using EPO.

With a potentially historic Tour around the bend, the current dustup over cyclists and doping warranted a response from Lance Armstrong himself. He has repeatedly, vehemently, and convincingly denied that any of his five consecutive Tour wins were drug-fueled, but the aspersions cast upon the Tour have, understandably if not justifiably, directed a new volley of questions toward the reigning champ, prompting Armstrong to write an open letter to the press.

“I am the most tested athlete on this planet,” he reiterated. “I have never had a single positive test result, and I do not take performance enhancing drugs.”

Still, uncertainty shadows both the innocent and the guilty: It is simply too easy to avoid getting caught. EPO has been in the peloton since the eighties, but it was undetectable in drug screens until 2000. Current tests work only if administered within six days of EPO use—performance benefits can remain for up to six weeks—so authorities look for indirect clues like an elevated hematocrit, a figure determined by the percentage of red cells in the bloodstream.

Healthy adult males have a hematocrit of up to 46 percent. To avoid busting athletes with a naturally high count, the Switzerland-based Union CycIiste Inter-nationale (UCI)—cycling’s governing body—set the acceptable level at 50. But anyone with a wallet-size centrifuge, hypodermic needle, and blood-thinning solutions can easily tweak down to a perfectly legal 49.9 percent in minutes.

So far, the most concerted effort to place controls on doping has come from the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA), an independent outfit created in the wake of the Tour’s 1998 meltdown that works with Olympic officials and public authorities to establish drug-monitoring standards. In March 2003, WADA finalized the World Anti-Doping Code, which mandates stiff two-year suspensions for athletes who use banned substances.

Unfortunately, the UCI, perhaps fearing that such a crackdown could damage its stars, has yet to sign on, making cycling one of five Olympic sports that, as of press time, hadn’t accepted the code. Failure to adopt could keep cyclists out of this summer’s Games.

Meanwhile, athlete testimony and insider tell-alls continue to surface, further battering cycling’s troubled image. Philippe Gaumont, a Cofidis pro who was busted in February for using EPO, told reporters he believes that 95 percent of Tour riders are still doping. Late in March, allegations arose about organized drug use on Spain’s Kelme team, killing the squad’s Tour de France hopes.

It may be impossible to ever know the true pervasiveness of the problem, or the guilt or innocence of riders. Further, gene doping, a science that would render current tests irrelevant, looms on the horizon. Throw in an event like the Tour de France—and the dollars at stake—and an immensely challenging picture emerges.

“It’s an elephant,” sighs Dick Pound, president of WADA. “There are very heavily entrenched entities in this, and a lot of economics involved.”

The two realities of the Tour—its enormous popularity and the specter of corruption—persist side by side. “If there was a large boycott—no one watching on TV, no one cheering along the side of the road—then maybe things would change,” says Yesalis. “But I don’t think the fans really care.”

Denis Zanette

Italy*Age: 32

D. 01.11.2003

Pro rider and stage winner in the Giro d’Italia. Died of a heart attack after a routine dental visit.

Marco Ceriani

Italy*Age: 16

D. 05.05.2003

Elite amateur who suffered a heart attack during a race and died two weeks later.

Fabrice Salanson

France*Age: 23

D. 06.03.2003

Young pro who died of a heart attack the night before the 2003 Tour of Germany, in Dresden.

Marco Rusconi

Italy*Age: 24

D. 11.14.2003

An amateur who died of heart failure in a shopping-center parking lot in Como, Italy.

Jose M. Jimenez

Spain*Age: 32

D. 12.06.2003

Won multiple stages in the Tour of Spain. Died of heart failure in a Madrid psychiatric clinic.

Michel Zanoli

Netherlands*Age: 35

D. 12.29.2003

Retired sprint specialist and onetime Tour of Spain stage winner. Died of heart failure.

Johan Sermon

Belgium*Age: 21

D. 02.13.2004

Promising amateur who died in his sleep of heart failure. Police are investigating his death.

Marco Pantani

Italy*Age: 34

D. 02.14.2004

Former Tour de France champion who was plagued by doping allegations. Died of a cocaine overdose.