The Road Goes on Forever and the Story Never Ends

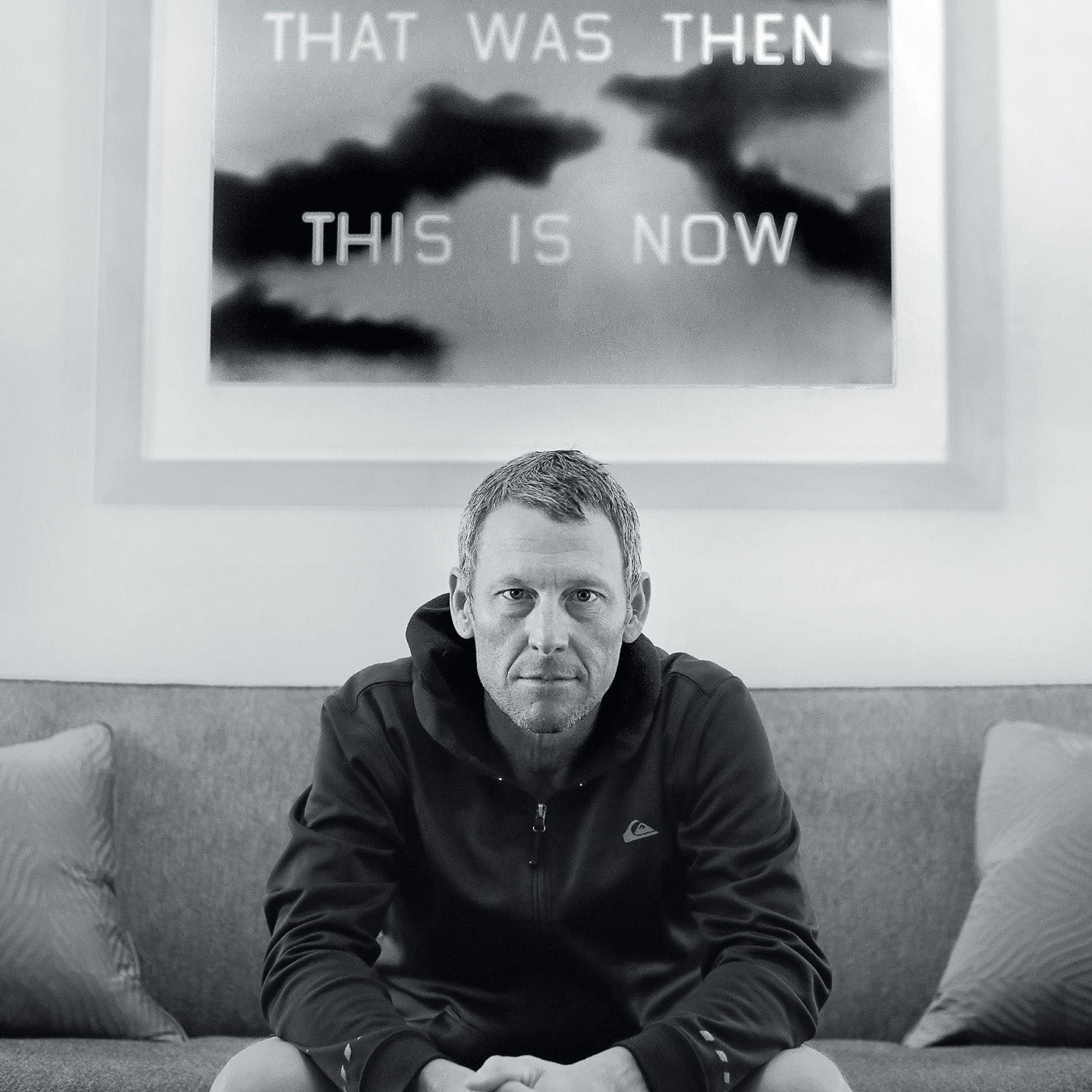

Lance Armstrong has a new narrative about his incredible rise and fall. Should we believe him this time?

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

Lance Armstrong is telling a story. He is seated at a boisterous table in a barbecue joint in Aspen, Colorado, along with his five children, ages 6 to 17, his fiancĂ©e, assorted friends, and a reporter. Behind the restaurant rise the lush green slopes of 10,000-foot Buttermilk Mountain, which in late spring is still partly covered with snow. Because Armstrongâs conversation is, as usual, peppered with profanity, his eight-year-old son, Max, occasionally shouts across the table, claiming a dollar for every f-bomb. This is their agreement.Ìę

âWe were driving to the golf club, just minding our own business,â Armstrong says. The familiar face is older now, more deeply creased, the famously electric, hazel-blue eyes offset with traces of gray hair. âAnd this guy pulls up alongside and flips us off. I couldnât believe it.â

for your iPhone to listen to more longform titles.

What he couldnât believe was not that he was given the fingerâsomething he has experienced often in recent years, both literally and figurativelyâbut that the driver of the car he was traveling in was given the finger, too. That would be Joe DiSalvo, the tall, curly-haired man now seated to Armstrongâs left, who happens to be sheriff of Pitkin County, which contains Aspen. DiSalvo and Armstrong are close friends. They were driving in DiSalvoâs unmarked police SUV.

âSo I said to Joey, âHow about a little red and blue action?â â Armstrong continues, his eyes lighting up. âI mean, come on, the guy is an asshole.â

This suggestion is so much in character that everyone laughs.

âThe last time I looked, it wasnât against the law to be an asshole,â replies DiSalvo, who is known for his enlightened approach to law enforcement. âBesides, we were late for our tee time.â

But the flipper didnât stop there. He swerved around DiSalvoâs SUV, then proceeded to pass a bus on the right. Now a law had clearly been broken. To Armstrongâs satisfaction, DiSalvo kicked on his siren and flashing lights and pulled the perp over. Armstrong, sensing the surreal potential of the moment, decided that it would be fun if he and DiSalvo both got out. You know, to mess with the guy.

âI told Lance he was staying in the car,â DiSalvo says. The offender was let off with a warning. DiSalvo and Armstrong made their tee time.Ìę

Armstrongâs tale is only a snapshot of his life in Aspen, where he and his family spend their summers in one of the countryâs wealthiest communities, but it captures something both of his still-bumptious personality and of his existence there: Âlively, gregarious, free-form, rooted in family. Most of Armstrongâs life revolves around his splendid blue-shingle home near the center of town, which he bought for $9 million in 2009 and is constantly full of children and adultsâa sort of standing cocktail party and kid fest that runs every night, all summer. There are occasional celebritiesârace car driver , a neighbor, is among themâbut mostly the attendees are what pass in Aspen for regular people.Ìę

âYou know that one house in the neighborhood where everybody likes to drop in and hang out?â DiSalvo asks me as we make our way from the restaurant to Armstrongâs. âThis is that house.â The traffic that night was relatively quiet by family standards. By my tally, 23 people came through, including four overnight guests from Austin, Texas. From all accounts and appearances, the Armstrongsâhis fiancĂ©e, Anna Hansen, two children by her, and three children by his first wife, Kristin, with whom he has a friendly relationshipâare a happy, close-knit famÂily. If you didnât know any better, you might think you were looking at an ideal world.

You would be very wrong. It is in fact a breathtakingly fragile world, one defined by loss and liability. It is a world, moreover, that very soon may be taken away forever.Ìę

In May, a civil trial is scheduled to begin in federal court in Washington, D.C., that will determine whether Armstrong defrauded his former sponsor, the U.S. Postal Service, by using performance-enhancing drugs to help him win the Tour de France and other races. If he loses, he could be forced to pay as much as $97 million, an amount that could ruin him financially, though at this point the trialâs outcome remains highly theoretical. Armstrong has already paid out $21 million in settlements related to his admission of doping, plus $15 million in legal fees. He makes no money these days from sports. He has a sizable investment portfolio, which spins off earnings, and two bicycle shops, and he makes a little money on the side as a speaker. But he is still a very wealthy man. If, as he reportedly told a friend in 2012, he was worth in the neighborhood of â$100 milski,â a judgment against him could certainly exhaust whatâs left of that amount, and then some.

The mega-lawsuit is not the only thing you canât see. Also invisible, amid the Âhappy thrum of the 5,800-square-foot house, is the staggering global scorn that followed the âs (USADA) condemnation of Armstrong in 2012 as a serial cheat and his subsequent public admission of drug use to Oprah. Nor can you see the depthless obloquy of the Internet, a place populated by uncountable numbers of people who call him a âcheating fuckâ and express the fond wish that he contract cancer again and die. You cannot see, or feel, the pain he experienced when many of his friends and colleagues deserted him or when he was forcibly separated from his cancer-fighting foundation.Ìę

But perhaps the most important thing you canât see is that the basic story has changed. Lance Armstrong has always been a human narrative machine. If you donât know that by now, you are either too young to underÂstand such things or have been in a tent somewhere on a Greenland glacier for the past 20 years. He is a living story, a set of interÂlocking, constructed narratives, invented and given life by him, delivered in a series of ascending climaxes. Armstrong lived inside his narratives, and they were terrific: from the one featuring the poor kid, raised by a single mom, who rose to become a world-Âchampion bicycle racer, to the one about the cancer survivor who won seven consecutive Tours de France and raised money to help millions of other cancer victims. Or the one, finallyâthis is where he lost control of the scriptâin which he suffered one of the greatest reversals of fortune of a public figure in American history, in which his legend was instantaneously obliterated.Ìę

There is a new narrative now. How could there not be? It emphatically does not feature a broken, friendless man sunk in drugs or alcohol or depression or anger or self-pity. This one is about a man who has rebuilt his family and his friendships, who has attempted to come to terms with how Âdeeply his fans felt betrayed and who says he is sincerely sorry for what he did and the pain he caused. Banned from most official sports, he has transformed himself as an athlete, too. He has reengaged with the world. This is the new story: a humbled man who is working to try to deserve the forgiveness of millions of people who once believed in him.Ìę

His enemies will tell you that this Tour de Redemption is as phony as Armstrongâs erstwhile claims that he rode clean. Itâs just his new way of manipulating a universe in which everyone is seen as his domestique, they say. So, in a world where atonement requires more than simple apologies, is Lance Armstrong really contrite? Is he really sorry? Is he really a new man?

To even begin to understand what Lance might be thinking now, you have to know how bitterly angry he once was about his downfall. Because he is by nature both arrogant and aggressiveââHe had one main tool in his toolbox: a hammer,â says his close friend and business manager Bart Knaggsâthere was nothing meek or humble or accepting about his attitude in the dark days following his fall from grace. His public in 2013 was an unalloyed disaster. He did not seem sorry because he wasnât sorry, and anyone could see that. âIf you go to Oprah, what you do is cry and crumble and get picked up and hugged,â says Knaggs. âAnd so, if Oprah loves you, the rest of us can love you, too. But if you miss steps one and two, she canât do step three. It doesnât work.âÂ

And he really, really didnât get it, even afterâor perhaps especially afterâall his sponsors and foundation colleagues and pretty much the entire cycling world had ditched him. On the day USADA released its report, he lost an estimated $75 million in sponsorship money. âWhen I did Oprah, my attitude was, fucking get over it,â he told me in an interview at his Aspen home in June. âMy feeling was, look at what we did. Look how the sport grew, look how the industry grew, and look how many people were affected because of Livestrongâs cancer work. Get over it. That was my attitude in 2013. I now understand that âget over itâ was not an option. People were upset, hurt, livid.â

He was angriest of all with the , which he had created, donated more than $5 million to, and helped to raise $500 million, and which, in effect, kicked him off the board. His doping admission had put board members, as fiduciaries, in a difficult position, not least because Armstrong had never hesitated to use his cancer work as a shield during the years he denied doping. His response to his curt dismissal was to fire off a scorched-earth e-mail to his former colleagues, some of whom were close friends, which prompted an equally blistering riposte from board member and prominent political consultant Mark McÂKinnon, who told a journalist that Armstrong âshowed a lack of remorse or any notion that he has to serve a cause greater than himself.â McKinnon, who has never reconciled with Armstrong, says the board had no other Âoption. âNo group of people loved and revered Lance more than the board members and executive team of Livestrong,â he told me. âHe was a good leader, and he has monster talents. But I donât think we had a choice. It was existential. It was to save the foundation from going down.â Rightly or wrongly, Armstrong felt betrayed.Ìę

In a world where atonement requires more than simple apologies, is Lance Armstrong really contrite? Is he really sorry? Is he really a new man?

Nor could Armstrong comprehend how easy it was for his former fans and once loyal chroniclers to dismiss his successâwhich included years of hard training and meticulous attention to the details of racingâas entirely the product of doping. He believed he had truly won all those races against well-funded, highly organized, and highly motivated competitors who were taking the same drugs and transfusions he was.Ìę

He was furious, too, with USADA head Travis Tygart, who had made him the poster boy for doping in a sport that was certifiably awash in performance-enhancing drugs. âMy name was taken out of the [record books], but the Tour was held between 1999 and 2005, wasnât it?â he told Le Monde in 2013. âThere must be a winner then. Who is he? Nobody came forward to claim my jerseys.â The doping statistics are indeed staggering: from 1998 to 2011, which frames the bulk of Armstrongâs professional career, 12 of 14 Tour de France winners and more than 40 percent of the eventâs top-ten finishers either admitted to or were officially linked to doping. USADA, meanwhile, had been miserably ineffective in enforcing its doping rules, which in turn had increased pressure on riders to cheat. The doping agency had doled out minor suspensions to a group of admitted dopers in exchange for their testimony against Armstrong, who alone was stripped of all his titles and banned for life from competitive cycling.Ìę

All this bad newsâalong with seven major books about the Armstrong scandalâwas now ricocheting through a life that had decelerated, as Armstrong puts it, âfrom 100 miles an hour to ten.â The phone stopped ringing, except with updates on lawsuits, which proliferated, including the big, apocalyptic one. Perhaps most damaging of all to his day-to-day life was his temporary ban by USADA from nearly all sports competition. His plan after retirement had been to remake himself into a world-class triathlete, and he had performed very well in a series of races before the ban went into effect. In April 2013, after registering for a masters swim meet in Austin, he was quickly barred by swimmingâs governing body, which announced that it would uphold USADAâs decision.Ìę

In an hours-long meeting with Tygart and another USADA official, Armstrong made this remarkable admission, as described by Juliet Macur in her 2014 book : âI canât get up in the morning without knowing that I have something to live for,â he told them. âFor me, thatâs training and competition. Iâm not training because I enjoy it, Iâm training because I have to.â Henceforth, he would have to train in what amounted to a void.Ìę

Close friends as well as reporters rememÂber the Lance Armstrong of the year following his disgrace not as broken or depressed but as furious at an unforgiving world. âI saw him that year [2013], and I have a very clear memory of it,â says former U.S. Postal teammate Christian Vande Velde. âWe were sitting in a bar in Aspen, and I just remember how angry he was, how angry and Âupset about what had happened. He couldnât talk about anything else.â Says Anna Hansen: âWe were scared and angry and a lot of things. He was definitely angry with the people in the cycling world, whom he felt had just turned their backs on him, which they did, more or less, and a lot of people would have argued that he deserved it. I think his hurt came out as anger.âÂ

There are Mamils everywhere, milling about in that peculiar halting way of people wearing bicycle shoes, adjusting their brightly colored kit, checking their tire pressure, grazing on protein snacks. There are about 400 of themâmiddle-aged men in Lycraâalong with a smattering of similarly attired women, watching the light come up over the Texas hill country and the sun break through the rain-torn skies. The June 3, 2017 is a century ride, followed by beer and barbecue and music on a private ranch near Burnet.Ìę

It is not formally a race. What is unusual is that it is run by a venture called , which was cofounded by Lance Armstrong and is based in Austin, where he lives most of the year. WeDu is at this point less a company than a concept, a notion that there is a large, underserved community of people who are drawn to endurance sports. It is an idea that also, not coincidentally, offers Armstrong a chance to participate in cycling races and rides from which he might otherwise be banned. He is not completely shut outâthis year he has ridden unsanctioned races in AriÂzona, Nevada, and Californiaâbut remains outside anything like normal cycling competition. His WeDu partner is a former professional racer (once part of the U.S. Postal team) and Silicon Valley executive named Dylan Casey.Ìę

âTo be a good cyclist, you have to love suffering,â says Casey, who until recently worked for Yahoo. âThe intent of WeDu is to create a community where like-minded people can engage and interact.â This summer, WeDu is hosting its second-annual , a mountain-bike event. And there are some less than definite plans to sell gear on the Internet, to host multisport festivals throughout the country, and maybe someday to make money doing it. For now, WeDu is a startup with minimal revenue.Ìę

Around 7 a.m., Armstrong addresses the crowd, looking trim in his gray WeDu kit. In spite of his troubles, there is still something inspiring about him, some instant, reflexive memory of his glory years that kicks in as he moves among the riders. These are his people, in more ways than one. Before he Âstarted winning the Tour de France, there was no such thing as large packs of Lycra-clothed accountants, hairdressers, teachers, and lawyers whooshing through suburban neighÂborhoods. He created them.Ìę

âGood morning, everybody!â he yells.Ìę

âGood morning!â they yell back.

âWho wants to get up at 5 a.m. and ride for 100 miles?â he asks rhetorically.

âWe do!â comes the reply, sounding out the name of his new venture.

âThereâs beer and barbecue and music when we get back,â he says. âIâll be the guy drinking three beers.â

And off they go. Armstrong, who at 45 is still in very good shape, though not nearly the rider he was when he retired nearly six years ago, will stay with a very strong lead pack, while the rest of the makeshift peloton labors along behind.

WeDu is part of Armstrongâs way forward, as he sees it, his chance to start living a Âfully new life and stop litigating the past. Now that he has settled all but one of the lawsuits against him, he has time to spend on it.ÌęAnother piece of that strategy is the , a weekly podcast in which he chats with sundry friends and celebrities, many of whom he knows personally, some of whom he calls out of the blue. Forward is a very Âdeliberately chosen word, and in fact, it defines Armstrongâs new narrative: others may want or expect to see him curled up in a fetal position in the dark, but he is moving ahead, not allowing himself to be crushed by the weight of the past.Ìę

The podcast has been running since June 2016. His guests have included Lyle Lovett, Brett Favre, Malcolm Gladwell, Rahm Emanuel, and Bo Jackson. In one episode, he interviews former teammates George Hincapie and Christian Vande Velde, both of whom testified against him in the USADA investigation. Both remain friends.Ìę

âThere was a freeze,â concedes Hincapie, one of the most prominent riders of his generation. âFor a while, we said what we had to say, and talking wasnât going to help anything. But we are still really close, good friends.â Armstrong, who also uses the broadcast to talk about his own life, is a surprisingly good interviewer. Though he will not say what his listenership is, his manager, Mark Higgins, says it has grown significantly, fueled in part by his ability to promote the podcast to his 3.8 million Twitter and 124,000 Instagram followers. In July, Armstrong expanded his media offerings to include Stages, a three-week Tour de France podcast in conjunction with this magazine. (He was paid nothing and received no expense Âmoney from șÚÁÏłÔčÏÍű, though he did get a significant platform, and his podcast drove traffic to șÚÁÏłÔčÏÍűâs website.) A month later, he reached an agreement to do podcast coverage of the Colorado Classic stage race, but concerns raised by USADA prompted organizers to cancel the deal.

âWhen I did Oprah, my attitude was, fucking get over it,â he told me. “That was my attitude in 2013. I now understand that âget over itâ was not an option. People were upset, hurt, livid.â

Armstrongâs main path these days is less an activity or a business than a way of thinking. He and his entire family have been in therapy for the past two years, a course of action he laughed off as late as August 2014 in an , explaining that âmy therapy is riding my bike, playing golf, and having a beer.â Family members now visit a counselor together and separately. âThe idea is total transparency,â he says. âI have worked hard at it.â He is still coming to terms, he says, with his forced separation from the Livestrong Foundation. When I ask how he feels about it today, he replies, âMy answer may not come off right, but those 15 years of hustling and building Livestrong, I donât miss the amount of work that tookâtraveling, grinding, asking for money, going to every chicken dinner. If it was my last day on earth, I would say I am proud of what I did. My head is high, my heart full, and no part of me wants to do more than what I am doing now, which is the one-on-one.â

By that he means his continuing work with individual cancer survivors, which consumes a considerable amount of his time and involves making phone calls, sending videos, and visiting patients. Such contact happens weekly. He is dead serious about doing this yet does not volunteer any information about it. âMy inbox on that used to be so full, it was impossible to accommodate everybody. Now the quantity isnât so great that I canât do them, which is cool.â

But the most profound change in Armstrong is his conviction that his disgrace and banishment were necessary and important events in his life. âIt has been a hellacious five years,â he says, âand in terms of the era, I donât think it was entirely fair. But I donât think I would change it. Anna and I have talked about this at length. With all of that, as a husband, father, friend, interviewer, whatever I am on a daily basis, I am better. I really believe that. Most people would say, âI hate to have lost all that money, I hate it that I got sued, I hate it that people talk shit about me.â But sitting here today, they did me a favor. I have a great wife-to-be. I have great children. I have a lot of time to spend with them. Also incredibly important is that I know who my friends are. How many people in the world know who their friends really are?â

And he saysâand this perhaps has the most meaning for people who know anything about himâhe is sorry. Not the âget over itâ sorry of the Oprah admission, but truly ashamed, and truly sorry.Ìę

He has expressed this sentiment any number of times publicly in the past two years, everywhere from the popular Joe ÂRogan podcast to the BBC. He talks about his behavior: âIt was literally like, finger in your chest, âFuck you, donât ask me that,â â he told Rogan. âWhen you are guilty, that is a real bad approach. Itâs the one that I took.â When talk-show hosts serve up softballsâthe sort of âeverybody else was doping, tooâ commentsâArmstrong refuses to take the bait. âIt sounds like youâre defending me,â he told Rogan. âI donât want that. I am of the belief that no one wants to hear that shit. They are upset.â To the BBC: âMy word doesnât matter anymore.⊠I get it, I need to be punÂished.â He repeatedly says he understands that many people cannot forgive him.Ìę

âPeople come up to me and say, âStop apologizing, you donât need to apologize anymore,â â he says today. âI donât agree with that. There were all sorts of people out there who had my back the whole time, even as the smoke got thicker and thicker. They said, âNope, we believe him.â For them it was even worse than a betrayal. They felt comÂplicit. Theyâre in their cycling club or at church, and people say to them, âLook how foolish you were to have believed this guy.â That is what I have to apologize for, for the rest of my life. And I am comfortable with that.â

Through all these exercises in atonement, all these expressions of regret, he maintains that he was treated unfairly. He will never change his mind on this. The apologies are for lying and suing people and damaging peopleâs reputations and finances, for betraying the trust of his fans. He believes that, in a sport where doping and lying about it was incredibly common, his punishmentâthe lost titles and the lifetime banâis beyond anything reasonable. But he says he is no longer angry about it. âI donât think Travis [Tygart] is a very honest guy, but I understand what he did and why he did it. All of that stuff he said publicly, that I was the greatest fraud in the history of the sport, forced young guys to put deadly substances into their bodiesâthose are not true. I know they are not true, and my teammates and the people I battled with know they are not true.â

His friends universally agree that, while he is still hypercompetitive and still tightly wound, he is a far more patient, tolerant, and considerate personâand a better friendâthan he used to be. âI can call him out on stuff now, whereas back in the day he had never heard ânoâ from anybody in twenty years,â says fiancĂ©e Hansen. âThatâs not good for somebody.â And though no one can know for sure what is in someone elseâs heart, his friends also believe that he is sorry in a way that he was not a few years ago. âI knew him for about a year of his fame, and the rest has been in disgrace,â says Joe DiSalvo. âI have seen the shift in him from the tenacious, angry-at-the-world guy to a man who nowâI donât know if âat peaceâ is a good term, because I donât know if Lance Armstrong is ever at peace, but who is certainly in a better place than he was before. I think he is happy with his life. I think he takes solace in the fact that his story is out. Thereâs nothing else. Itâs all exposed, and I think thatâs liberating.â

Not everyone buys this. Though it is impossible to quantify the numbers of people who canât forgive him, or donât believe heâs truly sorry, there is a persistent feeling that Armstrong hasnât come close to atoning for his sins, which include more than a decade of often harsh attacks, legal and otherwise, on people who challenged his legitimacy. in a New Zealand newspaper captures this sentiment. âArmstrong was beyond a simple drugs cheat,â the Âpaper wrote. âThe man was an evil empire. ⊠ArmÂstrong was more than happy to wreck lives, and has shown little to nothing of what most of us would call genuine remorse.âÂ

In the aftermath of his fall, Armstrong decided that he would apologize to some of the people he believed he had harmed, in some cases traveling long distances to do so. Some of these apologies were accepted; some were not. His former massage therapist on the Postal team, Emma OâReilly, who he had once called a whore and an alcoholic, accepted, and she even asked him to write the foreword to her . According to Armstrong, Filippo Simeoni and Christophe Bassons, riders whose careers and reputations he had damaged, both accepted.Ìę

Others have refused. Most prominent among them are Greg LeMond, three-time Tour de France winner, and his wife, Kathy. LeMond, who was an early, vocal critic of Armstrong, says that Armstrongâs campaign against him both hurt his reputationâhe was actually shunned in the sport for yearsâand cost his family tens of millions of dollars in revenue from canceled contracts with Trek and other companies. âWe lost our livelihood,â says Kathy, âand we spent $4 million in legal fees defending ourselves.â In 2015, the LeMonds and their attorneys had a four-hour meeting with Armstrong and his attorneys because there was potential litigation with , one of Armstrongâs former sponsors. Armstrongâs stated intention was to apologize. But according to Kathy, that never happened. âIt was very dismaying for me, because he never actually said he was sorry for what heâd done. He said he got caught in a wave of everybody doing this and some people around him had treated us terribly.â It is fair to say that Armstrong and the LeMonds are still bitter enemies.

Nor did his apology to his former teammate Frankie Andreu and his wife, Betsy, carry any weight. In 2005, the Andreus testified that Armstrong had admitted from a hospital bed in 1996 to using performance-enhancing drugs. The Andreus then learned, as the LeMonds had, that to oppose Armstrong was to cost them their employment and income and reputation. Though Armstrong telephoned the two to apologize on the eve of the Oprah appearanceââso he could say that he had done it,â says Betsyâhe later canceled a meeting with them and, still later, in a 2015 deposition, volunteered the factually unsupported claim that âFrankie had doped for his entire career.â Betsy and Frankie say they are weary from so many years of feuding. âI really donât want to see him,â she says. âI just want him to stop coming after us, lying about us. I know why he is out there saying he is sorry, because of the impending trial.â It is unlikely that Armstrong and the Andreus will ever reconcile, in part because Armstrong still denies the Andreusâ assertion that they heard him confess to doping. The Andreusâ testimony was the original cause of ill will; nothing is going to make it go away.

âBetsy and Frankie didnât have money to spare and spent money defending themselves,â says Kathy LeMond. âI asked Lance if he would please make financial amends to them. He owes them hard cash. When I said that, that is the most he raised his voice, and said: âNever.â When I asked Armstrong about the Andreus and LeMonds, he shook his head slowly from side to side. âMaking amends, apologizing, making it right with those affected is all I can do,â Armstrong says. âThat campââmeaning both the LeMonds and Andreusââis loud, and they have great stories, but I think itâs a smaller group than weâve ever thought. I really do. As long as you wake up and take a breath, they want you banned from breathing.â When I asked if he would consider writing checks to make amends, he said, âThat is not going to happen.â He will not say if his looming trial, with its potentially massive liability, has anything to do with .

All of which leaves that federal lawsuit, with its potential for financial destruction, as the principal obstacle in the way of Armstrongâs forward path. The case has a long and tortuous history, originating in the Âcareer flameout of another prominent U.S. rider and former Armstrong teammate, Floyd Landis. Landis won the Tour de France in 2006, the year after Armstrong retired, only to be stripped of his title after testing positive for doping. Landis launched a global campaign to prove his innocence. He started the Floyd Fairness Fund, which raised nearly half a million dollars for his legal appeal. He wrote a book defending himself with the now ironic title . When his appeal was denied in 2008, he went into a tailspin. Like Armstrong, he stormed at cycling officials and friends who had abandoned him and fellow cyclists who had unfairly gotten away with doping. Unlike Armstrong, he fell into a deep depression, during which he would sometimes take 15 painkillers a day, washed down with a fifth of Jack Daniels. (He was eventually ordered, under threat of criminal prosecution, to pay back the $478,354 he had raised from credulous fans.)

Shunned by most of the cycling world, including Armstrong, Landis had a revelation: he would rat out the lot of themâor, as he , âtorch the whole thing.â And that is what he did. In 2010, he blew the whistle, admitting his own doping, naming names, describing how the doping was done. His searing e-mail to USA Cycling morphed into a criminal investigation by the , and eventually into the USADA investigation that brought Armstrong down.

Not long ago, Armstrong's fiancĂ©e, Anna Hansen, was talking to their seven-year-old-son, Max. She was telling him that his father was one of the greatest cyclists, when Max interrupted and said, âYeah, but he cheated.â

Ten days later, Landis launched his own whistleblower lawsuit under the Âfederal False Claims Act against the men he said defrauded the Postal Service by taking its sponsorship money while doping. The main targets were Lance Armstrong and team director Johan Bruyneel, as well as various team owners, managers, and agents. In 2013, the federal government joined Landisâs suit and has since deployed a large team of lawyers. The Postal Service paid Armstrongâs team $32,267,279; under the False Claims Act, defendants, and Armstrong Âpersonally, could be forced to pay back three times that, or $96,801,837. The law specifies that the whistleblowerâin this case, the deeply compromised doper, liar, and cheater Floyd Landisâstands to make up to 25 percent of that, or a little over $24 million.

Landis is not on the list of people Lance Armstrong is now at peace with. To Armstrong, the worst thing about Landis is not the lawsuit. Itâs that, seven years after he filed, Landis is now telling reporters that it no longer makes much difference to him what happens. When asked about it by , he replied: âThe last couple years, you know, my lawyer deals with it and I donât really pay that much attention. I assume at some point there will be a trial. I donât mean to sound flippant about it, but I just donât care anymore.â Comments like this, which Landis has made elsewhere, infuriate Armstrong. âThere are very few things that piss me off anymore, but this is one of them,â he says. âMy family is at risk, and he doesnât care. Believe me, I care.â

In spite of Landisâs blasĂ© indifference, the case, having failed in two attempts at mediation, is now steaming toward a May 2018 jury trial. The lawyers for Landis and the Postal Service, who seem dead set on pursuing the maximum possible damages, face some obvious legal challenges. Proving that the original Postal Service contract was fraudulently induced as a result of Armstrongâs doping is relatively straightforward, thanks to Armstrongâs admission eight years after the contract ended. Proving that the harm that fraudulent contract caused outweighs the benefits the Postal Service received will be tougher. The Postal Serviceâs own commissioned studies, four of them, showed that its contract with Armstrongâs team was worth close to $140 million in global media exposure, showing, in other words, that the USPS got a good deal.Ìę

A key issue is to what extent the Postal-Landis legal team will be able to bring Armstrongâs character into play, as opposed to being restricted to talking only about damage to the plaintiffs. If Armstrongâs deceptions and aggressive behavior are allowed in testimonyâfrom witnesses that could include the Andreus and LeMondsâthe government could gain a significant advantage. That will also mean, however, that Armstrongâs lawyers may be able to talk about Floyd Landisâs character and motives.Ìę

Though Armstrong jokes grimly that the jury could render him homeless, begging for money with a tin can, that is not likely to happen. But, in a worst-case scenario, a jury could award damages that exceed Armstrongâs net worth, which mightâand we are getting pretty speculative hereâforce him to take refuge in Texas law, allowing him to keep the equity in his Austin residence. Armstrong once listed the house for $8 million; his equity in it is not known. He will have legal fees to pay. The bottom line: Armstrong could lose a gigantic percentage of his wealth, including his familyâs Aspen paradise. He is clearly worried about this and spends time thinking about it. According to one friend, he was devastated when he lost a motion for summary judgment in February that asked the judge to throw out the federal case. There is still the possibility of a settlement, which could happen at any time, and this is the outcome that Armstrong says he would prefer.Ìę

Whatever happens to his finances, Armstrong still has to live out his life in his skin as the âdisgraced cyclistââthe mediaâs favorite termâwho became the global symbol of doping. âMost people donât have to go through a public shaming and then have to look at their kidsâ faces,â says Anna Hansen. âThat part was really hard. We try to keep an open dialogue.â Not long ago, Hansen was talking to her and Armstrongâs son Max, then seven, about his fatherâs career. She was telling him that his father was one of the greatest cyclists, when Max interrupted and said, âYeah, but he cheated.â Lance, Anna, and first-wife Kristin have spent years explaining his fall from grace to the three eldest childrenâtwin 15-year-old girls, Isabelle and Grace, and 17-year-old Luke, who once got into fights defending his fatherâs reputation. With a lot of counseling and personal effort, family life has improved. But in Lance Armstrongâs world, there is no stepping away from the past. Max and his six-year-old sister, Olivia, are a stunning illusÂtration of this: they know virtually nothing of the Armstrong narrative. Not yet. âI will be having that discussion with them for a long time,â Armstrong says. âYou canât just say to a seven-year-old, âIt was a really bad time, and everybody did it.ââ

S. C. Gwynne () is the author of and .Ìę is an °żłÜłÙČőŸ±»ć±đÌęcontributing artist.