It almost never happened. Though he was a world-champion cyclist at 21, by 1998 Lance Armstrong was a 26-year-old cancer survivor who'd never finished better than 36th at the Tour de France and was struggling to reenter professional cycling. The big teams didn't want him, and he wasn't sure he wanted the sport. His first race back was the five-day Ruta del Sol, a February warmup for the long season ahead. He finished an encouraging 14th. But just two weeks later, while contesting the much more difficult Paris┬ľNice, he rolled to a stop in the middle of a cold, windy second stage and got off his bike. Even he doubted he would ever get back on.

Here, Armstrong's coaches, teammates, and closest friends recall their efforts to coax him back, the mental and psychological transformations that followed, and a miraculous Tour de France that ended ten years ago this month with a new American hero.

Too Much, Too Soon

MARCH┬ľAPRIL 2008

PAUL SHERWEN (cycling commentator and former pro cyclist): I remember Lance's result in Ruta del Sol. To me, that was already a great success. But Ruta del Sol is a startup race. Paris┬ľNice is the first vicious race of the season.

LANCE ARMSTRONG: I just didn't feel like being there, so I pulled over and said, “That's it.” It was an instinctual reaction, totally irrational.

BART KNAGGS (Armstrong's longtime friend and fellow racer from their junior days, now a partner in Armstrong's management firm): He had big expectations, and all of a sudden he was just one more guy getting pissed on in the rain, with grit in his teeth. He's saying, “Look, I don't need this. Maybe I'll go to school, maybe I'll get a job.” We started talking to people about things he could do┬Śbe a real-estate guy, a financial guy. But at the same time, we sort of came to a consensus: You know what? This is what he was born to do. Let's rekindle that passion.

CHRIS CARMICHAEL (Armstrong's longtime coach): I really remember one discussion. I said, “Look, you say you've proven enough to the cancer community because you got back to professional cycling and proved you were competitive. Dude, you pulled over and quit, and that's what everyone's going to remember.” He didn't like that.

I flew back home, and he called me and said, “All right, we'll do one more race,” the U.S. Pro. But he was like “Look, I gotta get out of Austin. I've just been playing golf and drinking beer. If I'm gonna do this, I gotta go flat out.”

So we started talking about Boone, North Carolina. Cool hippie town with a college. Really good atmosphere and some great climbing. Then he needed a training partner, and I remember saying, “Hey, what about [American Tour de France veteran] Bob Roll? He'd be perfect.” He's funnier than hell, and he was still racing on mountain bikes at the time. And Bob has a good way of getting a guy thinking about stuff in an introspective way, without being forceful.

PHIL LIGGETT (longtime cycling journalist and commentator): Bob and Chris were trying to straighten his mind out more than his body, because he took a real hammering in Paris┬ľNice. So they went up to Boone in April and they raced on the hard roads, seven hours a day in atrocious weather.

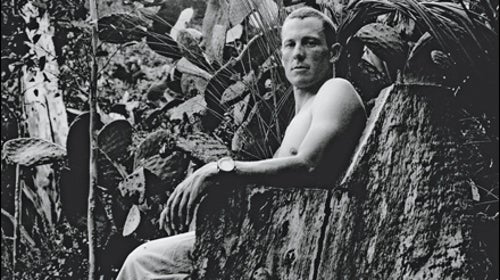

ARMSTRONG: It was just Chris, Bob, and me in a cabin, training long hours and eating at home. It was a monk's lifestyle that we ended up adopting for ten years after that. The weather was really, really bad, but we nutted up and we rode every day. I proved to myself that I loved what I was doing.

CARMICHAEL: The last day was 120 miles, and the guys were going to finish on Beech Mountain, a hard climb. Then I was going to load the bikes and drive the 30 miles back to the cabin. As soon as we hit the climb, Lance dropped Bob. I was following him, and he kept getting out of his saddle and really hammering. It's not even raining now; it's snowing. I just want to get through the thing, but he's attacking. There's nobody there, just a cow on the side of the road and me. I remember pulling up and rolling down the window, laying on the horn and yelling at him, pounding on the side of the car, saying “Yeah, come on!” like he was racing.

I don't know why.

We got to the top, and I remember exactly what he said to this day. It was “Give me my rain jacket. I'm riding back.”

This was a Thursday, and there was a race in Atlanta on Sunday. By the time we got back to the cabin, he was like “I gotta do that race.” I remember him arguing with the team manager because they didn't have race wheels for him. It really pissed Lance off. I was doing backflips, because he's better when he's pissed off. There it was. Game on.

Back on the Bike

APRIL 1998┬ľJUNE 1999

That spring, Armstrong didn't just reenter the race world; he tore through it. He finished fourth in the U.S. Pro, then won three smaller stage races in quick succession. He skipped the '98 Tour de France but entered September's three-week Vuelta a Espa├▒a, finishing fourth overall, just six seconds off the podium. He followed that up with fourth place at the world championships in both the time trial and the road race. “From July to August to September, who was riding better?” Knaggs says. “I don't think there was anybody.” After the season, Armstrong and his associates had their first serious discussions about the Tour de France, a race where he'd never before been a threat. It came together when they recruited recently retired racer Johan Bruyneel to manage the team. Bruyneel instituted a Tour-first mentality and, with Armstrong, diligently previewed every stage of the race. Their revolutionary approach would eventually serve as the model for all serious Tour contenders.

JIM OCHOWICZ (Armstrong's longtime mentor, former Olympic cyclist and coach, and founder of the 7-Eleven pro cycling team): Lance had gotten really beat up by the chemo and now he was starting to transfer back into someone who looked like a bike racer, but different than when he left the sport. A bit smaller, and his legs looked leaner.

SHERWEN: Oh, bloody hell. Fourth in the Vuelta, then fourth in the time trial and fourth in the road race at the worlds. The Vuelta, you could say, “It's not the Tour, not the Giro.” But then to back it up and do that at the world championships, that's icing on the cake. If you have a good end of the season, you usually have a very good following season. So we thought Lance could be a contender at the Tour, like top five.

CARMICHAEL: And remember, this is still a very young rider. He was only 26.

ARMSTRONG: I didn't even think about what the Vuelta meant with regard to the Tour until Johan and I hooked up and he said, “Dude, you can win it.”

JOHAN BRUYNEEL (former pro cyclist and team director for all seven of Armstrong's Tour wins): This was all new for me, because I was still in the mind of a rider. So I said, If I could decide on my own calendar to prepare for the Tour, without any other obligations, what would it be? By obligations I mean having to prove myself or having to satisfy sponsors who want us to race in this country or that country. So I took a blank sheet of paper and worked backwards from the Tour to make my dream calendar. We were lucky to have an American sponsor [the U.S. Postal Service] who wasn't really interested in any other races. It was all about the Tour. I think it wasa good thing that we were a little naive, because it was not a logical choice.

GEORGE HINCAPIE (Armstrong's longtime teammate): Johan got things a lot more organized. We didn't really have a Tour team, so to speak. It was just some American guys┬Śthat year we had seven Americans and two foreigners. But we tried to get the guys we had as good as possible, show them the mountain stages, work on their time trial, and just get everybody psyched.

CARMICHAEL: It was really different this time. I'd like to consider it a scientific approach, but a lot of it comes down to compliance. Before, Lance would commit for a few weeks at a time, but then he'd lose his focus. Now he gave a greater commitment. He realized he had a second chance.

BRUYNEEL: We spent a lot of time previewing the stages of the Tour. That was something that had never been done. Some people see a few crucial stages, but never as thoroughly as we did.

BILL STAPLETON (Armstrong's agent): I wasn't attuned to how committed he was until I went over there in early May. He was very focused on what I thought we could get him, in terms of bonuses, for winning. I remember walking away from that meeting thinking, This guy really thinks he's gonna win the Tour de France.

Crash

JULY 3, 1999

Armstrong finished several notoriously brutal spring races in 1999┬Śincluding Paris┬ľNice┬Śand took a heartbreaking second in April's Amstel Gold one-day classic. He also suffered several accidents, one of which sidelined him for two weeks. Then, heading into the Tour, his dedication to previewing stages nearly derailed his comeback.

HINCAPIE: We were doing the prologue course a couple hours before the start, trying to memorize the corners, and Lance wanted to see if he could do the last hill in the big chainring. We were coming down this straight, and he was looking down at his gearing. I was behind him, and a T-Mobile car pulled out right in front of him. I yelled “Lance!” He looked up at the last minute and swerved. He still hit the mirror and went down, but not as hard as he would have. It's kinda funny┬Śhis whole Tour history could have been over right at that moment.

First Taste of Yellow

JULY 3

A prologue is a short time trial at the beginning of a stage race, used primarily to put someone in the leader's jersey for the first real stage. Armstrong covered the 4.2-mile course in 8:02 and beat second-place Alex Z├╝lle, of Switzerland┬Śmost people's pick to win the Tour┬Śby seven seconds, an eternity in such a short event.

BRUYNEEL: It was confirmation of the fact that he was in top shape. And there was of course a huge morale boost┬Śthat first yellow jersey.

ARMSTRONG: You never expect to be in that position. I thought on a good day I would be top ten, top five maybe. It was surreal.

KNAGGS: It was nine in the morning in Aus┬ştin. I bet I talked to Stapleton and Carmichael for two hours each that day. I didn't get out of my boxer shorts until like two in the afternoon. I mean, holy shit, he just won the prologue in the Tour de France! He's got the jersey. Guys spend years chasing the jersey. Not chumps┬Śgood guys.

STAPLETON: We'd been in talks with Bristol-Myers Squibb since late 1997┬Śthey made the chemotherapy drug┬Śbut the deal had never gotten done. When Lance won the prologue, I remember picking up the phone, and it was this guy who I'd probably talked to 100 times. He said, “I'm embarrassed to be making this call right now, but we're ready to do this.” Full-page ad in USA Today, New York Times, Wall Street Journal: “This miracle brought to you by Bristol-Myers Squibb.”

A Tactical Coup

JULY 5

Stage 2 took the riders over the Passage du Gois, a cobbled path off France's west coast that's rideable only at low tide. Slippery, narrow, and with water on both sides, it was a section where passing would be nearly impossible. Armstrong's team fought to keep him at the front of the field as they entered the stretch. Though he surrendered the yellow jersey that day, he finished several minutes ahead of most challengers for the overall, including Z├╝lle and Spaniard Fernando Escartin, another favorite, who were caught behind a series of crashes.

BRUYNEEL: I was mostly worried about having the jersey and having to control the race. With all due respect, it was not a strong team. We had three or four strong riders and three or four others who were there because we had to have nine riders.

HINCAPIE: When the shit is hitting the fan and there are guys trying to get by on a road the size of a bike path, I'm there, 99.9 percent of the time. That's one of the reasons Lance always wanted me there┬Śbecause he knew I could get him through those situations. We entered [the Passage] in third or fourth wheel and came out with only ten or so other guys who didn't get caught behind the crashes. Some guys lost the Tour that day.

ARMSTRONG: The images from the helicopter are amazing. It was just carnage behind. There are dudes basically in the sea.

KNAGGS: Go back to '99 and take out the Passage du Gois┬Śit's a totally different race.

Reclaiming Yellow

JULY 11

The first real test for the overall contenders was the Stage 8 individual time trial in the town of Metz. At 35 miles, it would bring the strongest racers to the front before the Tour hit the mountains. The riders started at two-minute intervals, and Armstrong caught the three who'd started immediately before him, including the world time-trial champion, Colombian Abraham Olano. He ended the day back in yellow.

HINCAPIE: Yeah, he crushed that time trial. He passed Olano! He caught me, and I'd started four minutes ahead of him.

OCHOWICZ: He was showing them┬Śthem being the other sport directors and riders┬Śhow to do it for the first time, and they were watching. The first day I got to the race┬Śoh, man, all those directors who I tried to talk into signing Lance the year before were kicking themselves.

SHERWEN: His win at Metz confirmed that the prologue was a solid ride, but it didn't confirm that he would get out of the mountains. His weakest times in the Vuelta had been in the climbing stages.

BRUYNEEL: What I saw from Lance on a few of our training rides impressed me so much, because I know how fast it goes in the mountains. I remember saying to the mechanic in the car, Julien, “If that's the way he's going to ride in July, then we've got the winner of the Tour.”

KNAGGS: They didn't think Lance was going to go up hills. But he knew. He'd been doing all this work in the mountains, and he was just waiting for the first day.

│ž▒▓§│┘░¨ż▒├Ę░¨▒

JULY 13

Stage 9 marked the first day in the mountains, with a route that included the monstrous Col du Galibier and finished with a harsh climb to the Italian ski resort of │ž▒▓§│┘░¨ż▒├Ę░¨▒. It was here, most observers still believed, that Armstrong would finally crack.

LIGGETT: He blew everyone on the road away: Z├╝lle, Escartin. He tacks onto the climbers partway into the day, and then he jumps every one of them and rides alone to the finish. And all of those guys were already very far behind him in the overall. He could have ridden to the top alongside them and still had a huge lead. But he goes and hammers all shades of shit out of them. The look on Z├╝lle's face: “Where the hell am I? This guy is a robot.” The same with Escartin, a great climber. Lance just rode him away.

ARMSTRONG: My nature was always, and probably still is, to attack, to be aggressive and open up the race. Not always the smartest thing to do; there have been times when I've paid for that. But I felt like I was having a good day, and you might as well give yourself a cushion for future days.

THOM WEISEL (financier who backed the U.S. Postal Team and gave Armstrong his first pro contract after cancer): I was in the main car with Johan, right behind Lance, and we were just going nuts. We were hysterical. Lance is yelling in his earpiece, “How do you like them apples?” It was the best moment I ever had at any Tour.

SHERWEN: Once someone dominates a time trial like that and dominates a mountaintop finish, everybody starts to go, Uh-oh, we made a mistake here.

The Team

July 14

Though Armstrong now held a lead of more than six minutes, the Tour was not yet halfway over. With several more mountain stages to come, his teammates would have to ride better than anyone thought they could to defend the yellow jersey all the way to Paris.

HINCAPIE: It was up to us. Once the others saw that Lance was riding so well, they thought that their only chance was that he had a weak team, so they'd try and attack us. Nobody was confident in the team. We were criticized from all over the place. They all said, “They're just a bunch of Americans, they've never been there before. How are they going to protect the lead?”

SHERWEN: When you have absolutely no responsibility to yourself, you can push yourself harder. These guys all rode above themselves…because they felt that the man they were defending was invincible.

LIGGETT: [Teammate] Frankie Andreu was always a strongman; Tyler Hamilton was good in those days. Two of their riders never got to the finish: Jonathan Vaughters and the Danish rider Peter Meinert Neilsen. Christian Vande Velde was not a big player at that time, because he was too young. But George Hincapie will die for the master. He's such a fantastic guy.

WEISEL: Kevin Livingston was a big key. Hamilton was a talented climber, but Kevin was definitely the main guy that was able to stay with Lance in the mountains.

ARMSTRONG: All those guys were damn good bike riders. It's just that nobody had heard of them yet. We were the Bad News Bears. We didn't even have a team bus back then, just a camper. We were kind of crammed in there. But we didn't know any better. And the pressure┬Śsometimes the best way to cut it is to burp and fart and laugh. We tried to keep it light.

Hero and Villain

JULY 15┬ľ23

After │ž▒▓§│┘░¨ż▒├Ę░¨▒, the French press, still bitter over a doping scandal that had derailed the Tour a year earlier, began openly suggesting that Armstrong's performances were too good to be true. Simultaneously, the American public was starting to learn his name.

OCHOWICZ: I don't know if the French ever really understood what Lance went through with cancer, the dramatic change, physiologically and mentally. I think Americans are more open about it. I can't think of five people I know in Europe who have had cancer. They never talk about it.

CRAIG NICHOLS (Armstrong's oncologist at the Indiana University Medical Center and board member of the Lance Armstrong Foundation): I started receiving lots of phone calls, particularly from the French. Part of that, I think, speaks to the cancer stigma. To see him come back strong seemed paradoxical, and they kept asking what I had done. Jokingly, I said, “Well, we put in a third lung.” I don't think it translated well. There was just silence on the end of the line.

CARMICHAEL: It got pretty nasty┬Śpeople accusing him of using drugs, saying the cancer was fake. Crazy stuff. Hostile.

LIGGETT: He'd seen death in the face and he wasn't going back. And that's always his response when I ask him if he's taking drugs. “I've been on my deathbed, and I'm not going back there. The answer is no, and they can call that what they like.” He told me that years ago, to my face.

STAPLETON: It was pretty stunning at the time, going over there and seeing how the French press was reacting to this versus how the Americans were.

KNAGGS: People magazine was calling. The craziest stuff was going on.

HINCAPIE: I was getting messages from people I went to school with, people who didn't know what cycling was.

STAPLETON: Lance wasn't aware of what was happening in the U.S. He was in the Tour bubble. I get to France the night before the [Stage 19] Futuroscope time trial. Johan has everyone focused on the race, and in comes me, the agent from America, saying, “Hey, as soon as this is over, we've got to go to New York. Nike wants to do something, and we have this deal. It's in the papers, it's on TV. It's the biggest sports story of the year.” Lance was like “You're kidding.” He didn't believe me.

ARMSTRONG: I said, “Is it in USA Today, for example?” And Bill's like “Um…It's on the cover every day.”

The Final Blow

JULY 24

On the morning of July 24, the only thing that stood between Armstrong and a victory lap during the ceremonial final stage into Paris was a 35-mile time trial. With a massive 6:15 lead over second-place Escartin, Armstrong would have been forgiven for taking it easy. Once again, he crushed the field.

STAPLETON: I was not from the cycling world, so I didn't care if he won the time trial. I remember saying, “Hey, man, how about taking it easy? Stay on two wheels.” He looked at me and he said, “I'm gonna fucking win.” “OK, I got it. I got it.” I've learned since that time trials are where the champions win. You don't put it in park; you win.

ARMSTRONG: The time trial is called “the race of truth.” I think the yellow jersey has a certain obligation to show himself there.

LIGGETT: If you can do that and you're wearing the yellow, of course you can just lay down the fact that you're the best cyclist in the Tour.

Winning

JULY 25

On the triumphant final stage, Armstrong rode onto the Champs-Elysees to the cheers of a crowd that would never again be so small. From this point on, cycling, cancer, and Lance himself would not be the same.

OCHOWICZ: As far as Lance's family and friends, there were probably only 25 of us, at the most, waiting on the finish line, to see all the awards and do all the hugging and all that. No bodyguards; everybody just moved around.

WEISEL: We rented the top floor of the Musee d'Orsay for the victory party. There were probably 200 of us at most.

KNAGGS: We're sitting around after dinner, and all of a sudden Lance picks up his phone and leaves. He comes back and says, “That was cool. That was President Clinton.”

ARMSTRONG: It started hitting me then, all the stuff that Stapleton said.

OCHOWICZ: Once he got back home, he finally understood why we wanted him to be in the Tour back in the eighties and nineties. It creates a lot of heroes, and he had just become a Tour de France hero.

NICHOLS: About a year after Lance's diagnosis, when it was clear that he was going to be cured, I talked to Lance about his obligation┬Śas somebody who was cured┬Śto give back. I've had the same conversation with many other people who say, “Yeah, that's a good idea.” And they never do anything. But if Lance takes something on, he does it. It's actually been written about with different cancers, certainly with testes cancer: Over the last ten years there has been a noticeable migration to earlier-stage disease. That is, people are coming in earlier, which makes treatments easier and cure rates higher. And it's been dubbed the Lance Armstrong effect.

STAPLETON: The next week, we were going to New York to do Letterman and a bunch of stuff. Nike chartered a jet. We'd never been on a private plane. Lance picked up a bottle of red wine and looked at us.

ARMSTRONG: And I said, “Hey, boys, let's guess which race we're going to focus on next year.”