HE IS ALONE, but he is not alone. There are the schoolchildren by the road, waving shyly as he passes, and the idle men resting in the sparse shade. There’s a yellow Mavic-sponsored motorbike trailing him, with extra wheels in case of a flat, and a small convoy of official cars, creeping along at the pace he sets. Behind them, somewhere, is the peloton. A police motorbike draws even and a chalkboard is waved in his face: 40 seconds. He boosts the pressure on the pedals, turning perfect, powerful circles, extending his lead.

Give me your flat-tired, your worn out, your sweltering Europeans: Inside a Tour Du Faso transport wehicle, ferrying riders over a stretch of impassable road.

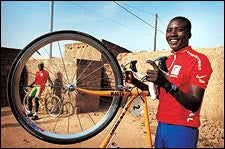

Give me your flat-tired, your worn out, your sweltering Europeans: Inside a Tour Du Faso transport wehicle, ferrying riders over a stretch of impassable road. Rasta Rouleur: Jérémie Ouedraogo at his home in Ouagadougou’s Tampui quarter, with Burkinabé

Rasta Rouleur: Jérémie Ouedraogo at his home in Ouagadougou’s Tampui quarter, with BurkinabéThe other racers can see him, of course. The road is as flat and straight as a stretched-out snake, and the lead he’s fighting to keep is less than a kilometer. When Jérémie Ouedraogo (pronounced “wed-DROW-go”) took off from the pack, sprinting into the clear, a few riders tried to chase him, but not for long. Perhaps they thought it was too early for a breakaway to succeed, or perhaps they saw the color of his skin and didn’t like his chances. But he went out anyway, and now he’s pushing a strong, steady cadence across the savanna, his wheels turning like the �����������Ի�é, the turning wind, which transports magicians and spirits across great distances, but not bike riders. He crosses a white line on the pavement: 25 kilometers to go.

He is a ���dzܱ���ܰ��� workhorse. When others are content to stay in the pack, sheltered from the wind, Jérémie attacks, he makes things happen. Today there’s a chance he could make it to the stage finish ahead of les blancsthe Dutch, Belgians, and Frenchbut it’s a slim one. It’s the eighth stage of the 11-stage race, everyone is tired, and he’s too far down in the standings to threaten anyone’s overall lead, so maybe they’ll let him go.

Or maybe not. The peloton is waking; the riders smell the finish. The wind is waking, too, pushing at his face, and because he is riding alone, he is doomed. The chalkboard again: 30 seconds. His legs feel heavy. Then 22, 15, 5. They swallow him.

An hour later, Jérémie watches French race officials give the stage winner’s jerseythe first awarded to a West African this yearto N’gatta Coulaibaly, 33, an Ivory Coast rider he has beaten many times in the past. Coulaibaly is so exhausted he can barely stand, his gold shorts stained dark from urine. His tears of joy mix with sweat as he does a barefoot dance, to the delight of a mostly African crowd that numbers in the hundreds.

Jérémie, a 27-year-old native of Burkina Faso, waits patiently to receive the red “combativity” jersey, given to each day’s most aggressive riderhis reward for those long kilometers alone. He puts it on quickly, kisses the podium girls, and smiles for the cameras. But it’s a loser’s prize, and he knows it.

IT WASN’T SUPPOSED TO BE THIS WAY. Not this year, with the new bikes and the training in France and half the European sports press descending upon tiny Burkina Fasoa desperately poor former French colony wedged between Mali, Niger, Ghana, and Ivory Coastto cover the Tour du Faso, the only professional, internationally sanctioned bike race held in the vast continental swath between the Sahara and South Africa.

After eight days, the host country still had nothing to brag about. Its dozen riders hadn’t managed to win a single stage. The highest-placed Burkinabé, 34-year-old Saïdou Rouamba, was lolling in 15th place, more than 15 minutes back, hopelessly out of contention. Jérémie Ouedraogo was in 18th, another three minutes behind. Most of the top places were held by European riders. There was a Moroccan in third, and another in sixth, but nobody from West Africa was anywhere near the front.

Foreigners have always done well in the Tour du Faso, which is held over 12 days every November. The first race was won in 1987 by a Russian, and though African teams have triumphed 9 of 14 times, Europeans have dominated in recent years, as the race has grown increasingly popular with over-the-hill pros and adventurous amateurs who make the difficult trip for various reasons. Some like the exotic locale, some come to rack up easy international racing points, and some show up out of altruismbringing hard-to-get bike parts for local riders, or supplies for the threadbare hospitals. All are inspired by the opportunity to pursue a purer form of a sport that in Europe has been wracked by drug scandals and excessive commercialization.

The result has been a higher level of racing but a tougher time for the West African riders, who face tremendous training and equipment obstacles in a region that has spent decades on the economic ropes. Like its neighbors in the Sahel region, Burkina Faso has little industry or natural wealth. It has few minerals, not much water, and nothing to draw tourists. The HIV infection rate is horrendous, and illiteracy is the norm. The average per-capita income is $230, barely enough to buy cycling shoes. There’s no filthy-rich oligarchy, as seen in Congo or Nigeria, but that’s only because there’s nothing much to plunder. (“Here, the poverty is equally distributed,” one European development worker told me.) Presiding over it all is Burkina Faso’s president, Captain Blaise Campaoré, 51, a military strongman who’s no stranger to corruption, having allowed his country to be used as a conduit for diamond and arms smugglers, and a safe haven for “every pariah in the world,” as an American diplomat once put it to The Washington Post.

The last homegrown rider to win the Tour du Faso was Ernest Zongo, in 1997, a year when only a weak Belgian team showed up. A Frenchman won in 1998, an Egyptian in 1999, and in 2000 a squad of Italian professionals swept five of the top six places. The 2001 event was shaping up the same waya Holland-based international team had grabbed the lead on the first day and hadn’t let go. Local newspapers like L’Observateur were turning Burkina Faso’s poor showing into a national crisis, accusing the home team of “always playing second roles.”

To make matters worse, this humiliation was being broadcast far and wide. The Tour du Faso 2001 was organized, for the first time, by the Société du Tour de France, the Paris-based body that puts on cycling’s biggest event every July and that stepped in to save the Burkina Faso race when it seemed on the verge of financial collapse. With a budget approaching half a million dollars, the strapped Tour du Faso took on relatively fancy trappings. There were nightly television feeds to Europe, better prize money for teams (about $30,000 in all), beautiful podium girls to kiss the stage winners, and five-time Tour de France winner Bernard Hinault on hand to present the maillot jauneyellow jerseyto the overall leader. It looked and felt like a miniature Tour de France, only hotter, thanks to Burkina Faso’s blast-furnace climate.

The French had invited six European amateur squadsfour French, one Belgian, and a group of riders from the multinational Marco Polo Cycling Teamto compete against ten African and Middle Eastern teams, including two six-man groups from Burkina Faso as well as squads from Niger, Mali, Ivory Coast, Cameroon, Morocco, Togo, Egypt, and Syria. To prepare for the race, a select group of Burkina Faso riders (including Jérémie) flew to France in September 2001 for six weeks of training in Brittany and Normandy, courtesy of the Société. Some even got new bikeswell, slightly used bikes, but still better than the patched-together wrecks they’d been riding.

But now they were racing like amateurs. No, worse: The amateurs were killing them. The Burkina Faso team leaderHamado Pafadnam, a tall, barrel-chested 28-year-oldwas having a tough time. The Tour du Faso was supposed to be his showcase, but he’d been plagued by flat tires and crashes, the result, he was sure, of black magic aimed at him by an unknown enemy. A few riders had shown flashesJérémie finished just behind the lead group in the first stagebut the rest seemed discombobulated. The head of Burkina Faso’s national cycling federation, an imperious man named Adama Diallo, had personally chewed the riders out, saying they were performing like cowards, always following the Europeans, scared to make a move.

Diallo knew little about racinghe’d played soccer as a youth, and volunteered to run the country’s cycling federationbut Jérémie had to agree. Sitting in the shade of an acacia tree, a few hours after the eighth-stage finish in the market town of Fada N’Gourma, he said of his teammates: “They are not in form. They are afraid to attack. When I went today, I called my teammates to join me, but none of them would.” Jérémie was disgusted but philosophical. There were three more stages, which meant three chances to win. His teammates were whispering about bad spells and conspiraciesbut Jérémie was calm, always calm. Only one thing was certain. Tomorrow he would attack again. It was all he could do.

AFRICAN CYCLING IS A LITTLE like Australian ice hockey. Few people know it exists, and nobody expects very much from it. But just as the Brits brought cricket to India and the Caribbean, so the French introduced cyclisme to their African colonies. Liberation was just over the horizon when, in 1959, the French staged an exhibition race in Ouagadougou, the dusty, sweltering capital of a colony that was then called Upper Volta.

That race, a short criterium (multilap event) featuring top European riders, went down in cycling history, but only because of its aftermath. The second-place finisherthe great Italian Fausto Coppi, a two-time Tour de France champion and the dominant rider of his erawent on a hunting safari after the race and fell ill. His doctors back home thought he had contracted influenza, but it was really malaria, and it proved fatal. Coppi died in January 1960, just 40 years old.

The seed of cycling had been planted, and the Ouagadougou race became an annual event that eventually grew into the Tour du Faso, under the stewardship of the late Thomas Sankara, a charismatic military officer who seized power in “La Revolution” of 1983. Sankara instituted a wave of reforms, and renamed the new country Burkina Faso (a phrase meaning “Land of the Incorruptible” in the two major native languages, Moré and Dioula). In 1987, he started the Tour du Faso, inviting a Soviet junior team to compete. Soon afterward, he was ousted, executed, and dumped in a pauper’s grave by his longtime friend and fellow revolutionary, Blaise Campaoré.

As of last August, it looked like the Tour du Faso might also come to grief. Burkina Faso’s national cycling federation had run out of money. There were no funds to sponsor races, to buy new bikes, or even to stage a national championship. But in late summer, the Frenchmotivated largely by lingering affection for the eventcame to the rescue.

“I wanted to be involved in that African race, because I’d seen it and I knew how amazing and human it was,” says Jean-Marie Leblanc, 58, the director general of the Tour de France and a guest of honor at the 2000 Tour du Faso. But the fuzzy feelings were severely challenged when Société staffers went to Ouagadougou in August and found that their money had mysteriously evaporated. This, with the Tour scheduled to start in just two months.

At least the course was set. Burkina Faso has only a few paved highways, all radiating from the capital like spokes. By necessity, a 1,302-kilometer stage event has to use most of the nation’s rather bumpy pavement, so the tour traditionally starts in Banfora, a small market town in the southwest, near the Ivory Coast border, and makes its way toward Ouagadougou, smack in the center of the Colorado-size country. From there it traces a series of out-and-back journeys, traveling deep into the bush one day, returning the next.

A few weeks and a few hundred grand of the Société’s funds later, all the other logistical problems were solved. The teams had been invited, the international press had been alerted, and a French-owned catering company had been hired to serve meals, complete with tiny wedges of Camembert. The Tour du Faso was ready to roll.

Or so it seemed. A few days before the scheduled October 31 start, the whole thing almost fell apart again. An Air Afrique strike stranded half the riders in various airports around Europe and North Africa. As participants straggled in, bleary-eyed and jetlagged, the Syrians and the Egyptians wound up canceling, as did the Togolese.

And then there was the problem with the cars, which the Burkina Faso Ministry of Sports and Youth was supposed to provide. Actually, the cars were finea fleet of gleaming-white Renault taxis that were to serve as team vehicles, plus another squadron of minivans from National Car Rental. Two days before the start, race officials ordered the cars and the chauffeurs to assemble at the Stadium of August Fourth, a state-built concrete monstrosity on the outskirts of town. There, in its moldy bowels, the French were informed by representatives of the Ministry of Sports and Youth that the price for the vehicles was going to be substantially higher than previously agreed. Or else there would be no Tour du Faso.

It was not a happy meeting. In the end, the Société ponied up, the Tour went on as planned, and the French shrugged their shoulders and muttered, “C’est l’Afrique.”

THE DIMENSIONS OF THE TOUR DU FASO mismatch become clear on the morning of the first stage, when the riders gather in the main square of Banfora. Amid a grove of tall trees, the teams unload their vans, eat lunch, and assemble their bikes: shiny, new aluminum and carbon-fiber machines for the Europeans, with brand names like Look and Colnago; ancient Peugeots for most of the Africans, with torn saddles, old-style toe clips, and electrician’s tape wound around the handlebars. Their helmets are battered, their shoes ratty.

The biggest crowd gathers by the Burkina Faso team vans, where Jérémie is preparing for the race in his usual manner, which consists of standing around in a green-and-white track suit with a Walkman glued to his head, listening to reggae star Lucky Dube. He is tall and handsome, with high cheekbones and lively eyes that project a quiet authority. While Pafadnam is the official team leader, Jérémie is the one his teammates look to in the races, the one they’ll fetch cold beer for afterward.

His bike leans against a tree, an orange-and-black Eddy Merckx that’s only a couple of years out of date. It’s not actually his bike; it belongs to the national cycling federation, which got it from the bike company owned by Merckxthe legendary Belgian who won five Tours de France in the sixties and seventieswhen the team traveled to Europe.

Jérémie hates it. For one thing, it’s too large; for another, it’s aluminum, stiff and dead-feeling. He’d much rather be riding his own bike, even though it’s heavy and old. The bike’s orange steel frame is more supple than aluminum, and more important, it’s his; after thousands of kilometers of training, his body has adapted to its dimensions. His nickname, “Rasta,” is lettered on the front fork. But he has no choice. The French gave him this bike, and how would it look if he were to refuse? He ditches the Walkman, stuffs a banana into his jersey pocket, and rolls to the line.

The race starts off fast, and the selection is merciless. On the very first climb, one of the riders from Niger is dropped. Hunched over the bars, his mouth halfway between a grimace and a gasp, he struggles to catch up, but can’t. The announcement goes out over Radio Tour: “Rider number 26 has been distanced by the peloton.” Within 20 minutes, four of his five teammates have also peeled off the back of the pack.

The Africans are not the only ones suffering. For some reason the stage started at 2 p.m., the absolute hottest part of the day, when shops close and nothing and nobody moves. The temperature has crested at 100 degrees Fahrenheit, and after a half-hour of racing, the red-faced Frenchmen at the back of the pack are waving their empty water bottles desperately.

Up front, the leaders put the hammer down, and the race explodes into a half-dozen small groups. Jérémie manages to join the lead breakaway but is dropped a few kilometers from the finish in Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso’s second-largest city. He winds up tenth, about two minutes downby far the best of his teammates, and the best West African.

Riders are still coming across the line 30 minutes later, long after Hinault has pulled the yellow jersey over the shoulders of the winner, a tall, dark-haired, 27-year-old Dutchman named Joost Legtenberg. The stragglers are mostly African, their mouths gaping, some wobbling on their bikes, utterly devastated. Two European riders come into view, with an African just behind. Seeing the finish line ahead, the African sprints furiously to beat them, and the crowdlifeless a moment agogoes wild.

WHEN JÉRÉMIE OUDRAOGO WAS SIX OR SEVENhis exact birthdate is unrecordedhis father, Sibri, took him into the bush, a day’s walk from their farm. Stand up straight, Sibri told him, like a man. Then he took a long knife and made three quick horizontal cuts on Jérémie’s right temple, just behind the eye. He repeated the cuts on the left side. Jérémie winced, but held back his tears. The scars that eventually formed would forever identify him as a Mossi, a member of the largest and most powerful tribe in Burkina Faso.

The Mossi had fended off Muslim raiders in the 16th century, slave traders in the 18th, and missionaries and colonists in the 19th before Ouagadougou finally fell to the French in 1901. The colonizers imposed brutally high taxes that pushed many Mossi to sell their livestock and go to work on French-owned coffee and cocoa plantations in Ivory Coast. Jérémie’s forebears were among the few who somehow clung to their land, tending their little plots of millet, sorghum, and peanuts, suffering the vicissitudes of rainfall and drought.

At home, one of Jérémie’s duties was to fetch water for the family, which was already quite large: He is the second oldest of nine brothers and sisters by his father’s first wife. (Now close to 60, Sibri has sired some 20 children with four wives, and shows no sign of letting up.) In the rainy season, April to June, this meant a quick trip to a well in a nearby field, not far from the family’s cluster of mud-and-thatch huts, one hut for each wife.

Every year the rainy season ended and the well dried up. Then Jérémie had to get water from the other well, five kilometers away through the bush. In the morning he would take a green plastic container, tie it to an old blue Peugeot one-speed that was the family’s only transport, and ride dirt paths to the well. The bike was too big for a seven-year-old, so he would stand on the left pedal and stick his right leg through the frame to reach the other pedal, holding the handlebars with his skinny arms.

It was years later on the same bike, a vélo ordinaire with a single speed and dubious brakes, that Jérémie entered his first race, in the nearby town of Boussé. He was 18, tall and strong by then, and he went along with a bunch of friends, turning his handlebars upside down so his rattletrap steed would look more like a racing machine. There were 40 riders there, on all kinds of bikes, and after riding around and around in a cloud of dust, he came in fourth. He won 300 francsabout 50 centsthe easiest money he’d ever made.

From then on Jérémie competed whenever he could, at the dusty races in small towns all over Burkina Faso. Most were multilap events through town streets, usually unpaved. Jérémie was a smart racer, and he clawed his way through the local scene. “He is très intelligent,” says Victor Duchene, a wizened 69-year-old Belgian who volunteers as the Burkina Faso team trainer. “And he is malin“clever, and a little ruthless.

In 1996, barely 21, Jérémie was selected at the last minute to ride the Tour du Faso with the national “C” team. A German won that year, but Jérémie placed 16thnot bad. Two years later, facing a tough international field, he finished third overall, astonishing everyone but himself. On the final day, the Frenchman who won looked at Jérémie’s bike in disbelief: It was a rusty old Peugeot, with ancient shifters and a gummy chain, the front fork painted Rasta red, green, and yellow.

His stunning performance earned Jérémie a spot on a club team that also provided him with his beloved Rasta bike. As one of the top five or six riders in the country, out of some 350 licensed racers, he commanded a stipend totaling $55 a monthenough to live on.

He began training full-time, often in the company of Hamado Pafadnam, who was his teammate and best friend. A poor boy from the northern town of Kaya, Pafadnam was big and gentle and had a killer sprint. Jérémie was wiry and resilient, but Paf was the closer, the one who could win races. The two became inseparable, training every day on the road northwest of Ouagadougou. In local and national races they made a powerful combination. “When we rode together,” Jérémie remembers, “nobody could beat us.”

But Jérémie wanted more; he has always dreamed of bigger things. Every July, he spends his days in a firemen’s bar in central Ouagadougou, glued to the live TV coverage of the Tour de France. Sitting there in the dark, nursing a Sprite or a Castel beer, he’ll watch the flickering images on the ancient set, which is enclosed in a metal cage to prevent theft. It’s a 10-kilometer ride from his home on the outskirts of Ouagadougou, in the Tampui quarter, but the bar gets good reception. Over the years he has watched Indurain, and Ullrich, and Armstrongall the greats. But no black African has ever made the starting line.

Maybe Pafadnam will be the first. He’s going to ride for a semi-pro team in Spain for the 2002 seasonthe first Burkinabé racer to go to Europe. Jérémie is a little envious of his friend, but he wishes him the best. So he’ll sit back and see how Paf fares abroad. And maybe his chance will come someday, too. But time is running out. He is 27 already. He has to make a move soon. When the Tour de France stage finishes, Jérémie pulls worn bills from his pocket, pays, and rides home to his wife, Kadi, their infant son, Evarice, and their two-room cinder-block house on a cratered, nameless street in Tampui. There’s a curtain for a door, a piece of corrugated metal for a roof, and insideagainst one walla long, low table laden with trophies.

EACH DAY OF THE RACE dawns cool and pleasant, the amber light slanting across the flat grasslands and the scattered baobab trees, their roots as massive as the buttresses of a French cathedral. But it’s all a deception. By 11 the heat is oppressive and queasy-making, which is why most stages start at 7 a.m. The air is filled with dust from the Sahara, blown down by a seasonal wind called the harmattan, the bane of the riders’ existence.

By the third stage, from Boromo to Koudougou, quite a few riders are looking ill. So are the French TV people, the commissaire from the International Cycling Union, and the guys from Mavic, the wheel manufacturer. Watching a hapless Belgian drop back from the pack for a midrace Imodiumhis shorts stained a repulsive colorHinault rolls down the window of his Mercedes limousine and cackles, “Il fait la chiasse!” He has the shits!

If la chiasse doesn’t let up, a racer’s next stop is most likely the car balai, or “broom wagon,” an ancient beige school bus that rumbles along after the very last rider, like an overfed lion stalking the weakest member of the herd. Nine riders bailed during the third stage, out of 76 starters. The fourth and longest stage, a 173.5-kilometer run from Ouagadougou north to Ouahigouya, close to the Sahara, promises to be a banner day for the wagon.

The riders leave on time, but around the car balai there is little sense of urgency. In fact, it is out of gas. As an underling scurries off to find some, the car’s chief takes the opportunity to lecture me gently on America’s various sins. “You give us your wheat, your milk, your soy oil,” he says, referring to the U.S. foreign aid that Burkina Faso relies on heavily, “but you don’t know how to be loved.”

His full name is Nocke Blaise Antoine Mamadou Bassole, comprising his Mossi, Christian, Muslim, and family names, but he goes by Blaise. A tall, dignified man in his sixties, clad in a light-gray polyester African suit, with a salt-and-pepper beard to match, he spends most of the year as a state railway inspector. As the commissaire of the car balai, he commands a staff of four, a driver and three helpers.

Bassole’s underling returns. Gas has been found, but now the car balai refuses to start. Soon we are all pushing the old bus, joined by commuters who have been press-ganged into service. The driver jams it into gear, but it dies. He opens the hood and fiddles with something, and the engine growls to life. We climb aboard and rumble into morning traffic, bound for Ouahigouya.

We quickly leave the city behind, trading swarms of buzzing mopeds for a dry, flat landscape reminiscent of west Texas. The road is rough and newly graveled, and before long we come upon rider number 22, Harouna Amadou of Niger, 26, pedaling along at a slow and stately pace. He shows no sign of stoppingin fact, he has outlasted his own bike, which gave out during the third stage. The Mavic guys loaned him a yellow Cannondale, and so we fall in behind him, maintaining a respectful gap.

Soon we find our first customer: Lionel Vedrine, a 29-year-old from central France. He’s had bad luck from the start, when he flatted about eight kilometers into the first stage. He rode the whole way alone, exhausting himself, and when the pace picked up today he couldn’t match it. “You have pain in your whole body, you are thinking of your sweetheart, and it is over in your head,” he says, collapsing into the seat beside me. “Shit.”

We pick up another tired Frenchie, then a burly Moroccan who has snapped his seatpost, and isn’t happy about it. Finally, Amadou pulls off to the side of the road and dismounts. But instead of climbing aboard the bus, he squats behind a bushla chiasse. He remounts and continues, unhurried as ever.

We pick up two more of Vedrine’s teammates, but Amadou still does not stop. Discontent rises in the bus. He is moving at only about 20 kilometers per hourat this rate, it will take him all day to finish. The European riders want Bassole and his crew to make him quit, but Bassole will have none of it. Whether Amadou gives up or slogs on, it’s his decision to make. One of the younger French riders waves a cold Coke out the window. “Come on in!” the kid yells, waggling the bottle in his face. “Stop now!”

“Pourquoi?” asks Amadou. Why?

“We have these expensive bikes,” Vedrine whispers, “but they don’t quit.”

We pull ahead and park in a small town, in the faint shade of a tree. Semicold Cokes appear, along with a pile of sinewy grilled chicken and a bunch of bananas. A small boy comes up to the window holding a metal can, looking at us with pleading, gooey eyes. “Vote Blaise Campaoré,” his filthy T-shirt urges, “for the blossoming of youth.”

Ten minutes later Amadou rolls past, and we toss our chicken bones out the window and rumble off after him. Before long he pulls over to the side of the road and stops. His bike is hoisted to the roof with the others, and he takes a seat toward the front of the bus. He isn’t even sweating. “Malade,” he says, indicating his stomach. He takes a banana from his jersey pocket and eats it, staring wordlessly through the windshield.

OUAHIGOUYA. YAKO. KAYA. Ziniaré. Fada N’Gourma. The caravan rolls across the countryside, one stage blending into the next. In the small towns and tiny farming villages, children are let out of school and flock to the roadside to wave as the race goes by. They wave at the publicity trucks; they wave at the cops on the motorbikes; they wave at the multihued swarm of racers. They wave at the winners, and at the very last riders, the ones struggling just to keep going. “Bon courage!” they shout.

Everyone agrees that the race is better organized than ever; there is good food every night, and the stages leave on time. But the stage finishes are remarkably unfestivesullen, in fact. Almost nobody claps. “There is something missing,” a Burkina Faso TV journalist tells me one night over beers. “Everything in Africa is like a party. But here, there is no fête Africaine.” One of the Belgians, who has raced the Tour du Faso for the past five years, agrees. “It has lost its African soul,” he mourns.

The reason is simple: The stage winner is almost always European. The Moroccans have a rider in third place overall, but they can’t seem to move him up. So the yellow jersey stays on Joost Legtenberg’s shoulders, even through the inevitable bout of la chiasse. As for the West Africans, they dropped out of contention for good with the grueling fourth stage, during which Jérémie lost a full 18 minutes after getting stuck behind a crash caused by a rider from Cameroon.

One night in Ouagadougou, after stage six, Jérémie goes to see Victor Duchene. Charged with tending to the riders’ physical needs, like food, fluids, medicine, and massage, the trainer is often closer to the riders than the team director. Victor worked with many of the greats, including Eddy Merckx and Greg LeMond; he spends a few weeks a year working with the Burkina Faso team, preparing them for the Tour.

Jérémie is discouraged. He is crying. He’d hoped for a top five finish this year, enough to get him noticed in Europe. But he’s so far behind, it’s hopeless. And his teammates still lack unity; each one seems to be riding for himself. He tells Victor he has decided to quit.

Victor has seen this before. “They are ���dz�������é,” he says later. They see the Europeans’ shiny bikes, their expensive sunglasses, their new helmets, and they become demoralized. Their legs feel heavy. They hesitate to attack, and instead only follow.

Look at me, Jérémie, he says. I am white, you are black. But you are just as strong as me. Stronger. You mustn’t be afraid, and you mustn’t quit. Victor knows that Jérémie is a good rider, a tough all-arounder. He is less strong than Pafadnam, but he has the smarts to make up for it, and he wants to win.

The next day there is a meeting, and it is announced that Jérémie has become the leader of the Burkina Faso team, replacing Pafadnam, his closest friend. Now there are tears, there’s shouting. But the logic is unassailable. “He showed in the Tour du Faso that he is the best rider in Burkina Faso,” Victor says later. And Pafadnam? Perhaps in his mind, he is already in Spain.

HE DREAMS OF ESCAPE, of long breakaways in the sun. On the morning of the ninth stage he takes off dangerously early, just three kilometers into the 126.5-kilometer dogleg from Fada N’Gourma to the town of Tenkodogo, joining a breakaway of five other riders: his teammates Lucien Zongo and Mahamadi Sawadogo; Martinien Tega of Cameroon; Sylvain Després and Arnaud Vettier of France. They are four Africans and two low-placed Frenchmen, so nobody pays them much mind as they build their lead, rotating smoothly to share the work. The gap grows to two minutes, then three, and then, after 40 or 50 kilometers, it starts to come down, dropping to two minutes and change.

At Koupéla, where the course turns south, their capture seems imminent. Jérémie urges his teammates to ride à bloc, all out, and they renew their effort. They are in a crosswind now, so they spread out across the road in a wind-cheating echelon. The gap begins to grow again.

Still working seamlessly together, they pass a large lake without noticing the crocodile basking on the muddy shore. Jérémie drops back to get water from his team car and stays at the rear of the breakaway, resting. His teammates Zongo and Sawadogo keep the pace fast while waiting for his sign.

He feels good, in part because he decided to ride his old bike again, but for other reasons as well. In earlier stages he felt weak at crucial moments, and he wonderedlike Pafadnamif someone hadn’t put black magic on him, known in Burkina Faso as “the Wak.”

Bike racers are superstitious in every culture, but especially in Africa, where magic is accepted as part of everyday life. If something bad happens, or even something good, a Burkinabé suspects the Wak is involved. Who would have done such a thing to Jérémie?

“Someone who does not want us to win,” he said gravely, implying that it might even be a teammate.

With five kilometers to go, he attacks, shooting up the right side of the road, almost in the gravel, and into the clear. His companions, momentarily stunned, are slow to react. But on the yellow Mavic motorbike, which has trailed the breakaway since the start, the driver groans. “He truly sucks,” he says to his passenger. “Why is he attacking now?”

Sure enough, he’s caught; his attack succeeded only in shedding his teammate, Zongo. With the gauntlet thrown, all cooperation ceases. After nearly three hours of working together, the riders have suddenly become bitter enemies: the three Burkinabé versus the three others. The six racers slow down, passing a dirty Shell sign, and Zongo claws his way back.

Jérémie sits nonchalantly at the back, watching the hostilities. With two to go, his teammate Zongo blasts clear down the left. The road slopes slightly downhill, so he gets a good gap. The Camerounais tries to chase Zongo down, but he can’t, leaving it to Després, the Frenchman. They are going quite fast now, over 55 kilometers per hour, and for a moment it looks like Zongo will make it all the way to the finish-line banner, rapidly approaching.

The road is like a funnel, sucking them toward the line. Després catches Zongo and keeps going for the finish, burying his head between his handlebars, with Jérémie on his wheel. But it’s too soon. He runs out of gas, and it takes almost no effort for Jérémie to swing right and float ahead, as though an invisible hand has given him a gentle push. His hands shoot up into the air as his bike swerves crazily across the finishing area, buffeted by waves of emotion from the crowd. He hears a woman scream with joy; his body tingles as he flies down the hill and into town.

JéRéMIE COMES TO REST in the shade of a small bar, several hundred yards past the finish line. There is a stampede, a sea of people surging toward him, small excited children and lumbering TV journalists, clearing a path with their heavy cameras. Everyone piles into the small outdoor bar, pressing him farther into the darkness, where he is wedged between a foosball table and a TV camera. A cold Fanta is placed in his hands; microphones are pushed in his face. “C’est une grande victoire pour notre pays,” he begins.

He is a champion, a hero. In his distinctive French, he thanks his teammates and describes how he was inspired by the crowds lining the final kilometers. A local journalist collars him, and he switches to his native Mossi tongue, the words tumbling out freely. Victor finds him, and they embrace. “Are you content?” Jérémie asks. Yes, Victor is content.

Soon, a representative from the Ministry of Sports and Youth drags Jérémie toward the podium, where he receives his white stage-winner’s jersey and his winner’s kisses. And the race officials breathe a collective sigh of relief. It would have been a terrible thing if the host country didn’t even win a stage.

Later, the Dutch will talk about what an easy day it wasalmost like a rest day. And others will whisper: Was it fixed to let them save face? Last year, Jérémie’s friend Mahamadi Sawadogo won the same stagebut only, the cynics say, because the Italian team let him. Perhaps this was the same. At any rate, the following day, stage ten, is very fastsuddenly lots of people are going for it. “Every African guy’s got it in his head that he can win now,” complains a Dutch rider.

MAYBE JéRéMIE HEARS THE TALK, maybe not. Certainly he knows the truth: To win a single stage, in a race that barely matters in Europe, is not enough. And so Jérémie decides to go for it again on the 11th and final stage, the most prestigious of the race, a 156.5-kilometer run from P(tm), near the Ghanaian border, north to Ouagadougou. The stage will end in front of the Moro-Naba palace, home of the Mossi king, who will be on hand to watch.

The stage starts off slow and festive, but the ridersthe 48 survivors of the race, that is, out of 77 starterssmell one last chance at glory. Twenty kilometers outside Ouagadougou, Jérémie finds himself in a breakaway again. In the ragged outer slums, the crowds lining the roadside are four and five deep. He can hear snatches of conversation. More than one person shouts, “Pafadnam! Pafadnam!” But Paf is not in the break. It is Jérémie, Sawadogo, a Moroccan, and a Camerounaisno Europeans this time. At one point they are ahead by more than a minute, but as they approach the city center they have barely 35 seconds, a sliver of a margin.

They enter the city from the east, dangling in front of the peloton, dodging potholes. At the United Nations circle they’re ahead by eight seconds. As they take a hard left at the Banque Centrale d’Afrique de L’Ouest, with one kilometer to go, Jérémie can hear the pack closing in from behind.

Sawadogo takes off solo, going for the win. Jérémie gives one last push for the line, but his legs will not turn. They have no powerhe wonders, is it the Wak?

The chasers swarm past, catching Sawadogo too, and a big, muscular Frenchman wins the stage.

Later, Adama Diallothe head of Burkina Faso’s cycling federationcomes up to Jérémie, removes his cigarette holder from his mouth, and gives him a questioning shrug, as if to say, “What’s the matter with you?”

Jérémie endures it, somehow. He respects Diallo, but Diallo has never raced a bike, so he has no idea how hard it is: the suffering, the loneliness, the mental torture. Jérémie merely shrugs back and mumbles a polite explanation. He watches the Mossi king, his king, give a splendid white robe to the overall winner, Joost Legtenberg, who looksthere is no other wordgoofy in it. Then he goes to look for Pafadnam, but he is gone.