FLOYD LANDIS appears at his apartment door wearing his usual expression: a sharp, knowing smile.

Floyd Landis

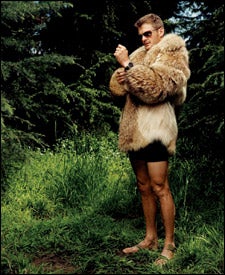

Floyd Landis, photographed in Los Angeles on April 6, 2006.

Floyd Landis, photographed in Los Angeles on April 6, 2006.Floyd Landis

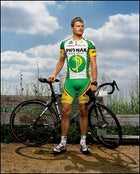

Landis is currently Team Phonak's lead rider.

Landis is currently Team Phonak's lead rider.Floyd Landis

Floyd Landis

Floyd LandisFloyd Landis

The guy who trains the hardest, the most, wins, says Landis. “period.”

The guy who trains the hardest, the most, wins, says Landis. “period.”“Welcome to the palace,” he says.

His gaze flickers playfully around, taking in the small room’s bare white walls and jumbled contents, which resemble a college dorm room after a mild earthquake. Here is the mantel clock frozen at 8:40, as it has been for two years. Here are the shiny piles of helmets and shoes; the tiny balcony stuffed with bikes. Here, sprawled on the couch, is fellow American cyclist Dave Zabriskie, a.k.a. Z-Man, Landis’s sometime roommate. Here’s the stereo vibrating with Ludacris. Here is the crammed bookshelf:┬áHow┬áthe Mind Works, by Steven Pinker, alongside thick biographies of Che Guevara and Frank Zappa. Should have known: Landis has a weak spot for revolutionaries.

All in all, it is a glorious squalor, a sophomoric playpen. Compared with the digs of the dozen or so top American cyclists who live here in Girona, Spain┬Śelegant continental apartments within the city’s charming old town┬Śthis tawdry cell, in an anonymous Lego-block building a mile outside the town center, constitutes a purposeful intrigue. Especially given that Girona’s most legendary residence, an impeccably renovated apartamento that had belonged to a certain retired Texan, is rumored to have sold to a Madrid businessman for $2.4 million. Which leaves $700-a-month Casa de Floyd┬Śbeyond whose dented door a select few have ventured┬Śemanating an ever-increasing sense of transition and mystery.

“I hear it’s completely disgusting,” one young American rider told me worriedly.

“Does he still ride around on that toy scooter?” another wanted to know.

Landis, 30, is the kind of person other bike racers like to tell stories about. A lot of it has to do with the narrative potency of his background, including his escape from a strict, oldfangled Mennonite childhood in Pennsylvania’s Lancaster County. A lot of it has to do with Landis’s penchant for offbeat, memorable feats┬Ślike riding wheelies after detaching his front tire or seeing how many bags of airline peanuts he can eat during a cross-country flight (28, for those of you keeping score). The result is that his fellow bike racers are constantly telling and retelling Floyd stories, creating a highlight reel that resembles nothing so much as old Warner Bros. cartoons. There is “The Time Floyd Dove into a Dumpster to Get a Pair of Shoes” and “The Time Floyd and Z-Man Drank 30 Cappuccinos in One Sitting” and “The Time Floyd Rode the Tour de France Nine Weeks After Having Major Hip Surgery.” The stories hang together because they have the same plot: a curious, unusually determined guy pushes against conventional limits, causing varying degrees of pain, humiliation, and triumph, not necessarily in that order.

Landis begins our visit by showing me something on his computer: an image of his grimacing face superimposed on the heavily muscled body of an ax-wielding maniac. Beneath the image, in stylish typescript, are the words I’M A HOMO.

“I e-mailed this to Lance and Z-Man and my wife,” Landis says, smiling hugely. “Z-Man and my wife got right back to me┬Śthey thought it was pretty funny. I never heard back from Lance, though.”

“I wonder why?” Z-Man asks, deadpan.

They contemplate this question with amused expressions, the two former U.S. Postal┬áteammates tapping easily into a convenient theme: Landis’s semifamous feud with another former teammate, seven-time Tour de France winner Lance Armstrong. The clash, which began in 2004 when Landis left Armstrong’s Postal team, and reached soap-operatic proportions during the 2005 season, is now officially over. But it would be unlike Landis and Zabriskie to leave the scab alone, never mind any attempt at diplomacy. So they joke about it. Landis and Zabriskie might be riding the Tour for rival teams┬ŚLandis the leader for Phonak, the 27-year-old Zabriskie a key lieutenant for CSC┬Śbut it’s instantly apparent why the two have been best friends since they first wore Postal blue together back in 2002.

“We were just wondering if, when this biking thing is over with,” Landis says, “we could apply to Harvard.”

Judging by the bookshelf, I offer, they might have a shot.

“We were thinking we’d get in based on life experience,” Landis says.

“And death experience,” Z-Man points out.

“We know how to kill things,” Landis says with enthusiasm. “Killing things can be extremely useful.”

“For eating,” Z-Man says.

I ask what they eat around here. Bike racers are prodigious eaters, yet the cupboards and counters are distinctly bare.”We eat a lot of eggs,” Landis says. “And we boil chickens.”

“Boiling chickens,” Z-Man says, in a Beavis-like voice. “Gotta boil the chicken.”

“That’s our philosophy, in a nutshell,” Landis says. “You gotta boil the chicken. Until the bird flu comes. Then the chicken boils you.”

“Boo-yah,” says Z-Man.

Landis offers another of his philosophies, one that comes courtesy of comedy writer Jack Handey. “If life deals you lemons,” Landis quotes, “why not go kill someone with the lemons, maybe by shoving them down his throat.”

“Lemons,” says Z-Man. “Leeee-mons.”

IT CAN GO ON like this for hours, and it does. And yet it would be foolish, for all the stoner-Zen appeal of their banter, to miss the fact that there is a great deal more going on beneath the surface. Behind Landis, on the curtain rod, hangs a clean new jersey┬Śthe color of lemons, as fate would have it, and proof of the most recent story: “The Time Floyd Won the Paris┬ľNice Race.” He earned the jersey two days ago, March 12, in the prestigious eight-day, 792-mile, Tour-contender-filled event, which was all the more impressive since it happened right on the heels of his dominating victory in February’s inaugural Tour of California. Throw in his dramatic win in April’s Tour de Georgia and it adds up to an early-season show of power and talent that can only be described as Armstrongesque. While Germany’s Jan Ullrich (T-Mobile) and Italy’s Ivan Basso (CSC) remain the officially sanctioned favorites, Landis now stands poised just behind them. The dark air outside this apartment is filled with voices murmuring the magical words: podium, July, Tour de France.

“Floyd’s the only American with a real shot to win the Tour. What happened in California and Paris┬ľNice make it obvious. He’s rock solid, he won’t freak out when things get nervous, and this year’s course exceedingly suits his abilities.” ┬ŚJonathan Vaughters, 32, U.S. Postal rider, 1998┬ľ99, and current director of Team TIAA-CREF

“Floyd is a strong time-trialist, a decent climber, and he’s not afraid. You can build your house on him.” ┬ŚAxel Merckx, 33, Phonak teammate and son of all-time great Eddy Merckx

“Basso and Ullrich can be beaten. That wasn’t true with Lance, but it is true this year, and it is possible that Floyd, along with some others, could do it.” ┬ŚJohan Bruyneel, 41, director of U.S. Postal, 1999┬ľ2004, and current director ofDiscovery Channel

“Look into Floyd’s eyes and you can see it┬Śhe’s like Cassius Clay walking into the ring with the cape on his shoulders. He looks at the other guy and tells him, ‘I’m the fucking greatest, and I’m going to kill you.’ ” ┬ŚFormer U.S. Postal soigneur/masseuse Freddy Viane, 48, who now works for Phonak

Whether Landis hears these voices or believes them is tougher to know. He is smart enough to say little in this regard, because he knows that this year’s Tour, marking the beginning of the post-Armstrong era, is one in which the rules are still being formed. After seven years of airtight control, the stage is wide open, with Landis playing the role of dark horse, the outsider who seems disorganized on the surface but who secretly has a plan┬Śa hard plan, calculated and ruthlessly logical┬Śand who sticks to it with Old Testament tenacity. Which is convenient, all in all, since that’s the role he’s been practicing for quite a while now. And that’s the other thing about Landis: When he practices something, he practices extremely hard.

LANDIS ADORES logic. There is no easier way to infuriate him than to say or do something that does not make sense. We are in a Girona restaurant drinking beer and shooting the breeze with the Z-Man when I begin a sentence with the phrase “Of course, it could be worse . . .”

“What does that mean, really?” Landis wants to know. “Of course it could be worse. If you are alive┬Śif you are standing up and have breath in your lungs to say those words┬Śthen, yes, I agree, you’re definitely right, it could be worse.”

Or later, when Z-Man mentions an athlete who spoke about “giving 110 percent.”

“Well, why not 112 percent?” Landis inquires, eyes widening with burning incredulity. “Why not 500 percent or 1,300 percent or 38 billion percent? I mean, if he can crank it up beyond 100 percent, why not? What’s stopping him, exactly?”

Other items on the Landis list include traffic roundabouts (stoplights are superior), French architecture, and, probably most of all, explanations for losing. The latter especially rankles. Bike racers hardly ever win (Landis’s three recent

“Everybody wants to say, ‘I couldn’t win because of this or that,’ ” he says. “To my way of thinking, it doesn’t matter if your goddamn head fell off or your legs exploded. If you didn’t make it, you didn’t make it. One excuse is as good as another.”

Landis takes a sip and leans forward in his chair. “There’s only one rule: The guy who trains the hardest, the most, wins. Period. Because you won’t die. Even though you feel like you’ll die, you don’t actually die. Like when you’re training, you can always do one more. Always. As tired as you might think you are, you can always, always do one more.”

Z-Man rouses, concerned. “I hope some 16-year-old doesn’t read this and then go kill himself on the bike,” he says.

“That was what I did,” Landis says, not missing a beat. “I read something like that, and I trained like that, and, yeah, I was pretty damn depressed for a while. Then it got better.”

So there’s no such thing as overtraining?

“If you overtrained, it means that you didn’t train hard enough to handle that level of training,” Landis says, his fingertip rapping the table for emphasis. “So you weren’t overtrained; you were actually undertrained to begin with. So there’s the rule again: The guy who trains the hardest, the most, wins.”

CASE IN POINT: Landis’s ninth-place finish in the Tour last year. While it would be easy to chalk it up to a flu-like illness that reportedly hit him during the Tour’s final week (which Landis will not admit to), the more pertinent reason was that he lacked what his trainer, Allen Lim, calls the “high-intensity intermittent component.” This is a complicated way of saying that, while Landis could keep a steady pace with race leaders up the steepest mountain, they could gap him by putting on short (ten-second-to-two-minute) bursts of maximum-wattage power. They possessed a tool that he lacked, which some call “high-end snap.”

“Riding for Lance, Floyd was a diesel engine┬Śhe had to go steady and strong,” Lim says. “But what we saw when we looked at the Tour numbers was actually encouraging. He hadn’t trained going into the red zone much, and this winter he started doing it. A lot.”

At home in Murrieta, California, Landis began to finish each climb with a prolonged breakneck sprint. He called it Steep Hill Interval Training┬Śa pleasing acronym┬Śand by winter the numbers began to come. He found he could push 1,250 watts for five seconds, as opposed to 900 the previous year┬Śa 39 percent improvement. Which means that on a steep, Tour-type climb, New Floyd will ride 3.7 miles per hour faster than Old Floyd for those five seconds, enough to open a gap of eight meters.

Landis also enjoyed a stress-free off-season, much in contrast with the previous year. In September 2004, a few weeks after Landis had signed with Phonak, team leader Tyler Hamilton and top support rider Santiago Perez received two-year bans for blood doping. (Perez accepted his ban; Hamilton’s final appeal was rejected in February.) The ensuing controversy temporarily endangered the team’s status in cycling’s ProTour organization and thrust Landis unexpectedly into the leader’s role. Last winter, Landis felt like he’d bought a ticket on the Titanic. This winter, however, he simply trained, tracking his progress on the sheets of graph paper he uses for a training log.

Asking most Tour contenders if you can see details of their training files is roughly like asking Coca-Cola executives to divulge their secret recipe. But here is where Landis again proves himself different. All his training and racing data derived from his CycleOps power meter┬Śwattages, intensities, times, cadences┬Śare an open book presided over by Lim, a 33-year-old physiology Ph.D. from Boulder who’s quickly developing a reputation as one of the sport’s brightest minds. On the Web and in PowerPoint presentations, Lim has shared all manner of Landis data, such as his average daily training between May 15 and June 12 of last year (3.5 hours) and his energy intake over that same period (174,000 calories, the equivalent of about 11 Big Macs per day). While the data holds abundant sex appeal for bike geeks, it’s also a sharp piece of psychological strategy. Here I am, the numbers say to the secret-obsessed peloton. Try and match it.

“I don’t see what the big deal is,” Landis says adamantly. “It’s just a number I produced on a certain day. What matters is what happens on the road.”

The peloton received its first dose of New Floyd at February’s Tour of California, an eight-day, 596-mile race that featured epic, Tour-quality landscape as well as the buzz-worthy presence of top American riders George Hincapie of Discovery Channel, Bobby Julich of CSC, and Levi Leipheimer of Gerolsteiner. All of whom were left behind when Landis utterly dominated Stage 3’s 17-mile time trial, hung on in Stage 5’s climb, and cruised to overall victory. Afterwards, Landis told Lim, “People keep saying I have good form now, but they haven’t seen anything yet.”

In Paris┬ľNice, they did. The eight-day “Race to the Sun” has long served as the unofficial kickoff of the European racing season, providing Tour contenders with a chance to test their engines. On a snowy, windy March day, Landis hit his new afterburners on Stage 3’s Col de la Croix de Chaubouret and blazed away from the peloton, leaving in his wake a roster of luminaries like Discovery’s Jos├ę Azevedo (1:26 back), defending Paris┬ľNice champion Julich (8:47), and Discovery’s Tour hopeful Yaroslav Popovych (9:37).

Getting the lead is one thing; managing it is another. Landis spent the next four days employing the sort of race tactics he’d learned at Postal, using the ample horsepower of his Phonak teammates┬Śincluding Koos Moerenhout of the Netherlands, Alexandre Moos of Switzerland, and Nicolas Jalabert of France┬Śto chase down threats. He also negotiated with other teams that shared interests in winning stages, an act of political control for which Landis required a different sort of afterburner.

The crux moment arrived in Stage 6, on the way to Cannes. Halfway into the race, a group of 19 broke away, and none of the other teams were willing to help Phonak chase them down. With the gap widening and the race becoming dangerously unstable, Landis decided to send a message.

At the base of a climb, he ordered his team to the front and told them to go full throttle. They blasted for three, five, ten minutes, and when everyone behind was gasping and hurting, Landis turned to address the peloton.

“You want more of that, motherfuckers?” he asked loudly. “Because if you do, we’ve got plenty.”

The race went smoothly the rest of the way. After it ended, I asked Chechu Rubiera, a former teammate of Landis at U.S. Postal, if Floyd had reminded him of anyone in particular at that moment. Rubiera just smiled.

BIKE RACING, AT ITS ESSENCE, is about pain. According to the hackneyed but ultimately reliable theorem, great bike racers draw their strength from fights they’ve encountered elsewhere in life┬Śagainst poverty, abusive or absent parents, injury, or illness (or, with surprising frequency, all of the above). But even in a peloton brimming with poor tough kids from the wrong side of the tracks, Landis manages to stand out.

“Floyd once told me that during races, it made him feel better to know that there probably weren’t too many other guys who’d shoveled out a septic tank in tattered shoes in the winter,” Z-Man told me. “So he’s got that going for him.”

The essentials of the Landis biography tread perilously close to myth: He was born in Farmersville, Pennsylvania, the second-oldest of six children in an observant Mennonite family. Rules were simple: no television, movies, uncovered heads for women, dancing, or anything that brought glory to the self instead of God. When Landis discovered mountain biking (which was permitted, so long as he covered his bare legs with cotton sweats) at 15, he improved so fast that, when he told his parents he wanted to pursue it as a career, they warned him of God’s wrath. When he wouldn’t listen to Scripture’s logic, his father, Paul, tried a different tack. He saddled Floyd with an endless list of strenuous chores: fixing the car, painting the barn, digging the septic tank. If the boy was too tired, the logic went, he couldn’t ride┬Śa theory that Landis quickly disproved by training at night, often returning to the house at 2 or 3 a.m.

“My parents are good people; we get along fine now,” Landis says. “But that life wasn’t for me. I was determined to get out, and I knew my bike was the only way.”

Landis won the junior national mountain-biking championship at 17, in 1993, and moved to California two years later. When a curious coach measured his VO2 max (generally thought to be a decent indicator of endurance potential), Landis scored nearly 90 milliliters per kilogram per minute, almost two points better than five-time Tour winner Miguel Indurain.

Before arriving in California, Landis’s American cultural experience had consisted mostly of a single viewing of Jaws when he was 12. (“I had to call my mom to take me home,” he says.) While his friends likened him to an unfrozen caveman, Landis set about exploring culture with the resolve of a scientist. Mountain Dew and Kid Rock were judged worthwhile; disco and Oliver Stone movies, not so much.

“His mind is very uncluttered,” says Will Geoghegan, 35, his former teammate on the Team Chevy Trucks mountain-bike squad. “He’s able to see and understand things more clearly than the rest of us.”

Landis saw that pro mountain biking was fading and decided, in 1999, to switch over to domestic road racing. He was spotted and signed by U.S. Postal in 2002 and quickly became friends with Armstrong, who appreciated Landis’s offbeat humor and, even more, his toughness. The latter quality shone most vividly in 2003, when Landis broke a hip in January, had surgery in April, and still managed to ride powerfully in support of Armstrong in the Tour.

Those good feelings came to an end in 2004, when Landis decided not to join U.S. Postal’s new incarnation as the Discovery Channel team. The decision precipitated a feud: What Floyd saw as independence, Armstrong saw as disloyalty. Over most of 2005, the former friends traded words, sharp elbows, and the occasional not-so-subtle gesture (Armstrong pointing derisively to the clock after beating Landis on a summit finish at last April’s Tour de Georgia; Landis yelling “Discover this!” after beating Armstrong in a time trial). At June’s Dauphin├ę Lib├ęr├ę, Discovery Channel adopted defensive marking tactics designed to prevent Landis from winning, even at the possible expense of the team’s own results. By week three of the Tour de France, Landis and Armstrong were shouting at each other from the bike. It was not a particularly smart fight for Landis to keep up; few people have tangled with Armstrong and come out the better for it. But it’s a measure of his stubbornness that he refused to back down.

“That’s Floyd all over,” Jonathan Vaughters says. “He’s exactly like Lance in that way┬Śthey’ve both got an angry core, a chip on their shoulder. And as Floyd matures, he’s getting more successful at channeling that anger in a positive way.”

When the 2005 season ended and Armstrong retired, the dispute quickly cooled. Both sides went out of their way to extend olive branches, a process that accelerated when Discovery team director Johan Bruyneel, with Armstrong’s blessing, took Landis out to dinner and tried to recruit him to join their team. (“Johan even paid!” Landis recalls with a smile.) While Armstrong and Landis are not as close as they once were, things are civil, even warm. When Landis won Paris┬ľNice, Armstrong e-mailed his congratulations.

“A year of that was too much,” Landis says. “I’ll take whatever responsibility is mine for what happened. In the race, it can be like a video game┬Śyou’re killing this guy or that guy. But then afterward you turn it off and everybody’s real people again.

“I saw firsthand what Lance did, and it was superhuman,” he continues. “I saw how his system worked. It’s not necessary for me to be like Lance in every way. But there are some things that I want to take from that and use.”

For instance?

“His boldness at taking charge of things. His willingness to say, This is what I want, and I’m going to take it. It’s very hard to compete against that.”

THERE ARE, OF COURSE, elements that Landis won’t use. While Armstrong was frequently surrounded by a whirling galaxy of trainers, corporations, private jets, and the occasional rock star, Landis has pared his life down to bare essentials: his number-crunching trainer, Lim, and his coach, former Postal rider Robbie Ventura, whom he frequently speaks with over the phone. His wife, Amber, remains in Murrieta with their nine-year-old daughter, Ryan. (“Amber used to come to Europe,” Landis says, “but it’s pretty boring. I’m riding or sleeping.”) While Armstrong desired information as though it were oxygen, Landis rarely answers e-mail, and gives out his telephone number only under duress. His sponsorships consist of a handful of bike-equipment companies.

“Everything with Lance was so big,” Landis says. “He was able to manage it all somehow. For me, that would be stupid. I train hard, I race my bike┬Śthat’s it. All the rest, that’s not me. I would be an idiot to try.”

Even as Landis talks, however, the landscape is shifting around him. Sponsors and media are ringing up, asking for some of his time. The Phonak general manager, John Lelangue, wants Landis’s advice on handling a few political matters; the team wants him to come to the Milan┬ľSan Remo race the following weekend.

There are also more fundamental matters to think about, specifically the fact that Landis knows he can’t go through the entire season at his present otherworldly level. While he takes exception when other riders suggest that he might be peaking too early for the Tour (“Peaking too early? What is that, Chinese? Let me translate: Blah-blah-fucking-blah”), Landis will shortly decide not to ride the three-week Giro d’Italia, in order to better manage his buildup to the Tour.

On the face of it, this year’s Tour is a good fit for Landis. While Basso and Ullrich remain the odds-on picks to win, it’s worth noting that each of them is also dealing with an unknown factor: Basso is attempting to win the Giro (a Tour-Giro double has been achieved only twice in the past 13 years), while Ullrich’s spring has been hampered by a recurrent knee injury and his now legendary weight difficulties. The course features two long time trials, a Landis specialty. If he can gain time in the TTs and use his new afterburners to hang with the top climbers in the key mountain stages (11, 15, and 16), he has a shot at the podium or even better. The theory is, while everybody watches Basso and Ullrich, Landis can sneak in. Though, as Ventura points out, “It’s getting harder to play the underdog card when Floyd keeps smashing everyone.”

No matter what happens, however, the Tour is certain to create more Floyd stories. Such as the one that happened last July.

It goes like this: A few days before the Tour started, Landis and Lim were training in a small town high in the Pyrenees of northern Spain. The training had gone longer than originally planned, and Landis awoke the last morning looking at a stormy forecast and a hellacious travel day. In order to make it to a pre-Tour Phonak team meeting in Tours, France, they were scheduled to drive two hours south to Barcelona, catch a plane for the two-hour flight to Paris, get picked up, then drive an additional two hours to Tours. Not a big deal under most circumstances, but on this morning, Landis didn’t want to hopscotch all over Europe like some business traveler. He wanted one last, hard ride.

Lim awoke to the sight of Landis pulling on his biking gear. The trainer was confused. Didn’t he have to pack up? Didn’t he have a plane to catch?

“Not anymore we don’t,” Landis informed Lim.

Lim still didn’t get it.

“What I’m saying is, Fuck it,” Landis said. “I’ll ride there.”

And so Landis did. He pointed his front wheel north toward France and started pedaling. He rode up and over the Pyrenees and down the mountain roads, into the vineyards of Limoux, following the road signs north. Landis rode for six hours, covering 130 miles, then got off his bike, stripped off his mud-soaked jersey and shorts, and hurled them off a nearby cliff. Donning dry clothes, he climbed in the car to drive the rest of the way with Lim. “You know how I got to the Tour last year?” Landis asked. When Lim shook his head, Landis grinned. “Lance’s private jet,” he said.

They arrived in Tours the following morning, a spattered VW Touran screeching up at the team hotel as the rest of the Phonak riders fixed Landis with expressions of baffled wonderment┬Śa moment that Lim described as “very Floyd.”

Back in his apartment, I ask Landis how he’s planning on getting to the Tour this year.

“I have no idea,” he says. “But I’m sure it’ll be interesting.”