THAT FIRST NIGHT in yellow, Victor Hugo Peña could barely sleep. He was alone in a single room, for once, with the phone turned off to keep the media at bay. The president of Colombia, Alvaro Uribe, had managed to get through to congratulate him, but after that there was silence. Peña’s eight U.S. Postal Service teammates—including Americans Lance Armstrong and George Hincapie, and Czech rider Pavel Padrnos, his roommate under ordinary circumstances—were long asleep. Peña should’ve been out, too, so he would feel fresh enough to ride up front the next day, as befits the leader of the Tour de France.

Victor Hug Pena on Velodrome

Speedy Gregarios: Colombian racers on the Bucaramanga velodrome

Speedy Gregarios: Colombian racers on the Bucaramanga velodromeVictor Hug Pena Training

The pause that rehydrates: Peña chugging root beer on a training ride

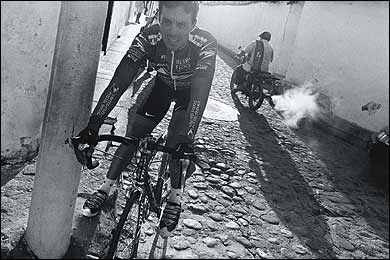

The pause that rehydrates: Peña chugging root beer on a training rideVictor Hug Pena Climbing Hill

Dangerous curves ahead: Peña and crew pass a military checkpoint outside Piedecuesta.

Dangerous curves ahead: Peña and crew pass a military checkpoint outside Piedecuesta.Victor Hug Pena in Medellin

Parts for sale: a bike shop in MedelĂn

Parts for sale: a bike shop in MedelĂnVictor Hug Pena Climbing Pescadero

“My dream is to ride for Colombia”: Peña on the infamous Pescadero climb

“My dream is to ride for Colombia”: Peña on the infamous Pescadero climb

Instead, his mind spun backwards, past the day’s 43-mile team time trial—the fourth stage of the 2003 Tour, which his Postal Service team had won by half a minute—to an evening in late May, when his dream had nearly expired in a flash of violence. He was sitting around at home with his parents, Hugo and Rosa, and his 25-year-old brother, Ismael, drinking hot chocolate and watching TV, when four thugs burst in, brandishing guns.

In an instant, they forced Peña and his family down on the floor. They claimed they were Marxist guerrillas, at war with Colombia’s embattled government, and demanded that Peña cough up the $300,000 in cash they believed he kept hidden in the house. Otherwise, they said, they would kill the whole family. Peña denied having any money and calmly invited the gunmen to look around.

This only angered them more, so they announced they were taking Ismael hostage. But after close to three hours of threats, Ismael, who’s slightly pudgy and very clever, clutched his chest and groaned, faking a heart attack. The intruders thought better of their plan—a dead hostage isn’t much use—so they ransacked the place and fled with the Peñas’ computer, some jewelry, and a few armloads of clothing.

It almost didn’t matter that the thieves were later caught and jailed, and that their “guns” turned out to be realistic-looking PlayStation toys. Until that night, Peña had never thought of himself as a target. Now he was one, solely because of his fame as an international sports star, and his life had to change. He sold his house—which he’d built himself, outside his beloved hometown of Piedecuesta, a ragged city of 80,000—and moved his family into a gated compound in nearby Bucaramanga, a leafy, relatively quiet city 200 miles north of Bogotá.

That was the easy part. It was harder to come to terms with what the attack meant for his future in a country that he loves and never wants to leave.

“You are a different person now,” the police told him that night. “You are not a normal guy anymore.”

At last, lying on that rumpled hotel bed in France, with cycling’s most coveted maillot hanging off his chair, Peña knew what the cops were talking about. Though his countrymen had made their mark on the Tour de France for two decades, often dominating its mountain stages, he was the first Colombian ever to wear the yellow jersey. Before, he was modestly famous; now he’d become a national hero. Back home, the celebrations were still going strong, and tomorrow the whole world would see him on their sports pages, proving once again that his poor, scarred nation belonged in the big leagues of bike racing.

The next day, Stage 5, the 29-year-old Peña rode like he had wings. All the way south to the city of Nevers, the TV motorbikes jostled for position around him. Any other team would have defended Peña’s lead to the death, but he knew that wasn’t part of the Postal script. The fact that he was the overall leader this early in the Tour was a bit of a fluke, and the team’s brain trust didn’t intend for it to last long.

“I wanted him to get rid of it as soon as possible,” concedes Peña’s boss, 39-year-old team director Johan Bruyneel. Having Peña in yellow distracted everyone from the team’s only goal, which was to help Lance Armstrong win his fifth Tour. Peña’s moment of glory had to give way to a reality that defines the life of every support rider: His role was to sacrifice himself for the team leader. Still, at day’s end, Peña retained his one-second lead—over Armstrong himself, awkwardly enough.

On Peña’s second day in yellow, with temperatures in the nineties, the peloton blazed south to Lyon, and TV viewers watched Peña drop back to the team car and stuff his yellow jersey with water bottles—perhaps the first time a Tour leader has performed such a lowly task. What those viewers didn’t realize was that Peña himself had volunteered for the errand. The next day, the race hit the mountains and Peña lost the jersey for good, to 33-year-old French superclimber Richard Virenque, who won the stage.

“My job at that time,” Peña recalls without complaint, “was not to be the winner of the Tour.”

IN A WEIRD WAY, it was a compliment that the gunmen chose Peña: It proved he’d arrived. Three years earlier, Colombia’s best-known cycling hero, 38-year-old Luis Herrera, had been kidnapped from his home, south of Bogotá, the country’s capital. But he was released within 24 hours, as if the kidnappers realized they’d made a mistake in targeting such an icon.

In 1984, Herrera was a member of the first Colombian amateur team to race in the Tour. Then a skinny 23-year-old, he stunned the cycling world by spanking two of France’s best riders, Tour winners Bernard Hinault and Laurent Fignon, on the grim switchbacks of L’Alpe d’Huez, to win the race’s toughest mountain stage. The following year, riding for the brand-new CafĂ© de Colombia professional team, Herrera won the Tour’s prestigious polka-dot jersey, awarded to the best climber in the race.

To this day, Colombia remains the only developing nation to produce world-class cyclists, from Herrera and his teammate Fabio Parra, who finished third in the 1988 Tour, to current stars like Peña and Santiago Botero, of MedellĂn, who won the climber’s jersey in the 2000 Tour and claimed the world time-trial championship in Belgium in 2002.

One reason for Colombia’s success is topography: The vast equatorial nation is divided by three ranges of steep Andean mountains, with peaks topping out at almost 19,000 feet. To get anywhere, you have to climb, and for decades Colombia has produced riders with the endurance and power to fly uphill.

Another has to do with the poverty brought on by Colombia’s long-running civil war, which began as a political disagreement in the late 1940s but has escalated into what Colombian writer Gabriel GarcĂa Márquez has called a “biblical holocaust” of violence that has claimed well over 300,000 lives. Only about half the country is under government control; the rest belongs to a collection of leftist guerrilla groups, the largest of which is the 18,000-strong Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia, better known as FARC.

Colombia is also beset by right-wing paramilitary organizations that battle the guerrillas and also engage in “social cleansing”—death-squad murders of drug addicts, prostitutes, and homosexuals. Both sides use kidnapping and cocaine as sources of funds, while the government has sopped up more than $2.5 billion in U.S. aid since 2000 to fight rebel groups on both sides. Last year, the war claimed between 3,000 and 4,000 casualties.

It doesn’t help that Colombia’s annual per capita income is only $1,950 and that only one urban household in 12 owns a car. But that fact explains why nearly all of the country’s great riders, including Peña, have come from working-class families that use bikes as basic transportation.

The upshot for bike racing is that tough times produce tough people. “Their lives are so hard that I think they appreciate the physical and mental suffering the racers go through,” says retired American rider Andy Hampsten, 42, who raced in Colombia in the mid-1980s and again in 1995.

Still, there are plenty of poor, mountainous countries where cycling hasn’t seized the public imagination. So why Colombia? Because it has a great bike race all its own: the Vuelta a Colombia, a grueling two-week stage event that’s been run every year since 1951. Like the Tour de France, the Vuelta got its start with help from a national newspaper (El Tiempo) that was looking to boost circulation. Thanks to heavy press coverage of the race, cycling grew in popularity throughout the 1950s, with help from visiting European riders like the legendary Italian Fausto Coppi, who’d won both the Tour de France and the Giro d’Italia in 1949 and 1952. In 1958, Coppi got schooled by the locals on epic high-altitude climbs like MedellĂn’s 19-mile Alto de Minas.

Over its 53-year life span, the Vuelta has survived coups and economic chaos, and its very existence has helped reassure a jittery nation. “If the Vuelta is going on, then Colombians know all is well with their world,” says British journalist Matt Rendell, 38, author of Kings of the Mountains, a 2002 history of Colombian cycling. “The Vuelta means that roads, electricity, food, hotels, and all the infrastructure you need to run a national race are functioning properly.”

The Vuelta is also a hell of a tough race; most of its 14 stages involve climbing. The most notorious ascent is the 38-mile La LĂnea, which rises 6,500 feet, topping out around 11,000 feet. Starting in the 1970s, foreign riders began coming to Colombia to train and race at altitude, since much of the country is above 8,000 feet. To their surprise, the locals often smoked them.

“You always wondered, How would these guys do against the Europeans?” says 43-year-old Chris Carmichael, Lance Armstrong’s coach, who raced in Colombia during the seventies and eighties as a member of the U.S. national team. “And then they went to Europe and kicked some ass.”

Herrera’s success set off a rush on Colombian talent. In 1991, 45 Colombian riders started the Vuelta a España, Spain’s three-week nationwide stage race. But the Colombians didn’t always find happiness in Europe. In Spain, team directors treated them like mere water carriers, or gregarios, for their Spanish stars. Between Herrera’s heyday and 2000, when Santiago Botero rose to prominence, dozens of Colombians were lured to Europe, only to fizzle out after a year or two of abuse and mismanagement.

Now things are looking up again. In addition to Peña and Botero, a half-dozen new Colombian stars—among them FĂ©lix Cárdenas, 31, who has won the climber’s jersey in the Vuelta a España and took a mountain stage in the 2001 Tour de France—are knocking on the door of European success. Meanwhile, Peña and his friend RaĂşl Mesa, director of the Colombia-based Orbitel team, are pursuing a difficult but intriguing dream: to gather the country’s best riders into a new all-star squad, one that they hope will resurrect the glory days of CafĂ© de Colombia. (Colombia/Selle Italia, the Colombian-Italian descendant of that team, has fallen to the second division of world cycling rankings and is not eligible for the Tour.)

With Peña, Botero, and seven committed support riders, such a team would have enough horsepower to contend for overall wins in races like the Giro d’Italia and possibly the Tour de France. While most of their compatriots have been pure climbers, Peña and Botero possess the speed to place well in time trials, which are crucial to success in major stage races. Botero has already finished fourth overall in the Tour, in 2002, and was favored for a podium spot the next year before a stomach virus felled him.

For Peña, the idea of a resurrected national team represents a chance to show the world what he can really do—and to inspire a new generation of Colombian riders. “That’s my dream,” he says. “To go to Europe with a Colombian team.”

But for the time being, Peña’s job is to ride himself into the ground to help Lance win his sixth Tour, while his good friend Botero, riding for Germany’s T-Mobile team, will do the same for Lance’s main rival, one-time winner and perennial runner-up Jan Ullrich. At 30 and 31, respectively, Peña and Botero are no longer young; both men are running out of time to unshackle themselves and go for it.

EARLY ONE SUNDAY morning last January, I met Peña outside his apartment building in Bucaramanga. Erika, his wife of one month, was still sleeping upstairs. A security guard dozed in a chair by the door, clutching a semi-automatic pistol.

Peña had brought out his old carbon-fiber Giant, for me to ride, and within minutes I could see why he has so many friends in the pro circuit: He’s funny, friendly, and generous to a fault. Like Lance, Peña is a former swimmer, and his back and shoulders are still dense with powerful muscles. Seated on his bike, he resembles a jaguar coiled to pounce.

As we set out, Ismael followed us, driving Peña’s brawny Ford Explorer, hazard lights flashing. Because of Colombia’s frequent extortion kidnappings, top cyclists never train alone. Pedaling out of the city, we were joined by Peña’s coach, Absalon RincĂłn, 45, a tall man with curly hair who has worked with Peña for years. The city street merged into busy four-lane highway, and then it started to rain.

At a bus stop, we met up with Olmedo Capacho, a quiet but friendly 31-year-old pro for Colombia’s Orbitel team, which races throughout Latin America and sometimes in Europe. There were also three older guys, wealthy local businessmen with paunches and expensive Trek and Cannondale bikes, and two up-and-coming 18-year-olds, Jorge Jimenez and Jaime Bueno, riding ancient, battered European road bikes.

As we passed through Piedecuesta and the road started going up, the businessmen turned back; the rest of us went over the top and dropped into a dry, rocky canyon. The rain stopped, and the Colombians flew deftly over the slick road’s many potholes. At the bottom of the canyon, the road passed through a military checkpoint and crossed over the fast-flowing and muddy RĂo Sogamoso. Then it rounded a bend and tilted upward again. This was Pescadero, a brutal climb in the Vuelta a Colombia, rising more than 6,000 feet in about 18 miles.

“In the race,” Peña said, “you make this turn and you think, My God, I cannot make it.”

I was thinking the same thing. Without a word, Capacho handed me a congealed lump of panela, the brown sugar that Colombian cyclists eat instead of PowerBars. As it dissolved on my tongue, I found new inspiration. We settled into a rhythm, joined by a leathery peasant riding an old mountain bike. His cycling shoes and shorts were ratty and worn, but he kept up easily. Bogotá-bound traffic streamed past us.

“Normally, man,” Peña said, “this is one fucking lonely road.”

In Colombia, lonely means dangerous. Last year there were 2,200 reported abductions nationwide—many carried out in rural areas by communist guerrillas or right-wing paramilitaries. Peña still vividly recalls a training ride years ago, on a remote mountain road near Bucaramanga, when three guerrillas stepped into his path. Under their ponchos he spied telltale bulges that he took to be weapons. He was trembling, afraid they would kidnap him for ransom. But they recognized Peña and waved him along. He said he’d never climbed so fast in his life.

I had never climbed so fast in my life, either, but my attempts to keep up with the Colombians were hopeless. After a few more miles, they increased the pace slightly; soon they were several curves ahead, still riding easily toward the sun.

PEĂ‘A AND BOTERO are Colombia’s two most well-rounded cyclists, but that doesn’t mean they win races in Colombia, where the climber is king. In 1997, Botero led the Vuelta a Colombia for a stage, but when the race hit the mountains, he could barely finish. Peña’s best Vuelta showing was eighth.

“In Europe, I can be a climber,” he says. “In Colombia, I am no climber.”

That was evident from the get-go. “In my first race, on the first climb—the first rider dropped was me,” Peña remembers. He was 19, a late starter because his father had long refused to let him ride competitively. Hugo Peña had been a national track-cycling champion in 1974 and rode the Vuelta a Colombia for several years, delivering telegrams by bike to make ends meet. He believed the cycling life was too difficult; better for Victor to hang out at the pool and watch girls. Victor had obviously inherited his father’s athleticism, though, and he swam well enough to win two national championships in the breaststroke. In the end, Hugo relented and let him ride.

As it turned out, Peña could do something most Colombians couldn’t. On the velodrome, he demonstrated the kind of relentless speed that wins time trials and pursuit races. Those skills made him a hot property. “A Colombian who can time-trial is basically a complete rider,” says Bruyneel. “Because they can all go uphill.”

In 2000, riding for Vitalicio Seguros, a Spanish team, Peña won a time-trial stage in the Giro d’Italia—a huge triumph for a Colombian. His reward? A season of abuse from his Spanish team’s director, which eventually led the hot-tempered Peña to challenge the man to a fistfight on the team bus during the Vuelta a España.

After that season, it looked as if Peña would end up like so many Colombians racing in Europe: homesick and burned out. But then Bruyneel placed a call to Peña’s agent. He remembered seeing Peña perform well in 1998, Bruyneel’s last year as a racer. After negotiating a handshake deal for a low- to mid-six-figure salary, Peña joined the team that had helped Lance Armstrong win two Tours de France.

In January 2001, Peña flew to Tucson, Arizona, for what he thought would be a two-week training camp with his fellow Postal support riders. Instead, Lance himself picked him up, and they drove out to a cabin deep in the woods on Mount Lemmon, which rises north of the city. It was just the two of them: Lance, the millionaire superstar, and Peña, the poor kid from Piedecuesta, who spoke no English at all. Every day they rode five or six hours on the empty desert roads, always finishing with a long climb back to the cabin.

While the team atmosphere was more relaxed than Peña expected, he’d never worked harder. Along with Viatcheslav Ekimov and George Hincapie, Peña became one of Postal’s designated hard men, the guys who ride up front, chasing down dangerous breakaways. Postal’s enforcers are so good, and so feared, they can quell other riders’ ambitions with a sharp word—or even a look.

Even so, helping Lance win doesn’t mean Peña’s job is ever secure. After his two-year contract ended, Postal cut his salary by more than a third, with little explanation. “He’d had a medium season,” says Bruyneel, unapologetic about the brutal economy for gregarios.

To everyone’s surprise, Peña didn’t complain. The money still went a long way back home, and there were certainly advantages to riding for the Tour-winning team while waiting for his chance to ride for Colombia—and for himself.

LAST JANUARY, on Peña’s final weekend in Colombia before heading to training camp in Southern California, he and I went to a race in the cold, mountainous province of Boyacá, just north of Bogotá. This is Colombia’s cycling heartland, home to many of its best riders. When cycling’s world championships were held here in 1995, on a course that started at 8,500 feet and climbed nearly 1,200 feet per lap, barely 20 riders managed to finish the 165-mile race. Three of them were locals, including Oliverio RincĂłn, whose tall, hawk-nosed brother, Daniel, is Peña’s newest Postal Service teammate.

Saturday morning dawned clear and crisp, and we made our way to the red-roofed town of Tuta for a small local race. The center of town was already blocked off, with the riders busy getting ready on the main square. Besides Peña and RincĂłn, there was FĂ©lix Cárdenas, whose nickname is El Gato—”the Cat.” Also on hand were two Vuelta a Colombia winners, Libardo Niño and Jose Castelblanco.

Several of the big guns here figure in Peña’s and RaĂşl Mesa’s plans to form the Colombian dream team. Mesa estimates that he can field a 20-rider team for $3 million, less than a third of Postal’s $10 million annual budget. The top support riders would earn between $30,000 and $50,000, far less than they’d command in Europe. Peña would be happy to take a pay cut from his six-figure Postal salary, and Botero is willing to join, too—”If it is real,” he told me.

The main problem is finding a sponsor. Prices for coffee—Colombia’s biggest legal export—have hit rock bottom, and other sources of Colombian funding are scarce. Mesa and Peña have been trying to persuade the national flower-export board to sponsor them; to field a team for 2005, they’ll need to have everything organized by this September, when riders typically sign contracts for the following season.

If the Colombian team does come to fruition, they probably won’t be the types to complain about bad road conditions. The Tuta circuit looked downright sketchy, with dirt-strewn corners and sharp speed bumps on the straightaway into town. Someone set off an unnerving string of firecrackers, and everyone’s head whipped around; an oompah band struck up, restoring calm. The town priest gave a blessing, praying that there would be no crashes that day, as the riders bowed their heads. Then they rolled off, led by rifle-toting soldiers on motorbikes.

The race was being broadcast on the radio, and you could hear it blaring from every bar and house at full volume. After about ten laps of picturesque Tuta, a fast-moving group of Colombia’s finest pulled to the front: Niño, Cárdenas, and Daniel RincĂłn. Peña bided his time in the pack until five laps to go, when he sprinted clear of the bunch and easily caught the lead trio. Niño and Cárdenas attacked, trying to shake the Postal pair. RincĂłn almost dropped off on the climb, but he recovered, and they all ended up bunched together on the last lap. Coming into town up a short, steep hill, Cárdenas tried to slip away, shooting over the speed bumps, but Peña flew past at the last second to take the win.

By the time I returned to the town square, Peña was engulfed in a scrum of reporters and fans, packed ten deep around their gran campĂ©on. The band struck up again, and somebody started launching huge bottle rockets, which exploded high above the church and drifted back down to earth. Peña bounded up on the stage, where he made a short, serious speech and then popped open a bottle of champagne, liberally spraying the audience, the other riders, and his ecstatic father, Hugo. It was a rare taste of victory for a man who’s almost always riding for others.

Afterwards, there would be a picnic for all the riders, with plenty of beef and beer, but first there were more long speeches and another blessing by the priest. “We are all gregarios,” he reminded the crowd, “for a leader in another world.”