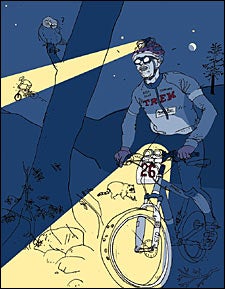

IT’S 3:30 a.m. AND DARK AS COAL, and we’re hurtling through the forest on bicycles. Numb with exhaustion, bleeding, primeval, we duck eye-gouging tree limbs at the last second, bounce madly off boulders, skid through hairpin turns, slingshot over jumps into abysses of blackness.

A narrow bridge, a swooping turn, an ascending trail, then a bunnyhop onto a singletrack cutting up through the trees. The bobbing lights of riders on the switchbacks above compel me to put my mind into my legs. It’s as if I’m riding inside a tunnel. The tunnel moves with me, vanishing behind my rear wheel. I spin out in the first dust-bowl dogleg, cut tight and catch it right on the next turn, and go wide, thumping rocks, through the next. It’s steep, but I can still maintain cadence. Sweat’s burning my eyes and oiling my thighs. My chain is grinding, my legs are groaning, and my mind is trying, in its foggy, debilitated condition, to block out the searing in my lungs.

Suddenly there’s a rider in front of me, and before I can yell “Track!” he has pulled off to the side. As I crank by, he gives me a push on the rear and shouts, “Go for it!” with such enthusiasm that I want to stand up on the pedals and hammer. I catch another rider and she gives way, dismounts, and shouts, “Go, man, go!” I pass a half-dozen riders on the uphill, all of us trying to survive this night of the living dead, and every one of them shouts heart-buoying words of encouragement.

Then I hear heavy, fast breathing. Before I can look over my shoulder, I’m overtaken by a rider as if I were standing still. “Hang in there!” he squeezes out. I try to catch him, but he vanishes into the black night.

After ten more minutes—which takes an eternity—the uphill, at a stroke, becomes a downhill, and I’m shooting through rutted turns, attempting to maintain some semblance of control. I have momentarily released my death-grip on the brakes when the beam of my helmet light illuminates the rock.

It’s a diving board of black stone. The trail jags right and zooms straight off this gangplank, and my brakes are squealing like terror-stricken piglets as I go airborne. My rear wheel flips above my head, sending me catapulting over the handlebars. I execute a double twisting somersault into the talus. The cyclist behind me lands the jump but slams on his brakes and skids to a stop next to my picayune wreck.

“That was something. You OK?”

I stand up, and the rider, an anonymous competitor in this 24-hour sufferfest, takes the time to check me over, making sure I don’t have any bones protruding.

Shaken, I say thanks several times.

“Hey, we’re all out here together.”

BARE LEGS AND ARMS hanging out the van windows and the CD player blaring Jerk with a Bomb and energy drinks rolling across the floorboards and homemade brownies and bags of beef jerky sailing from lap to lap.

Like a hundred other mountain-bike teams from around the West, Big Daddy Meats (the name of the local butcher in Laramie that sponsored us with four pounds of beef jerky) is on a late-August pilgrimage to California to race the 24 Hours of Tahoe, one of the toughest all-day, all-night cycling events in the country.

“You’re joking!” I’ve just learned that Pat Fleming, my noble teammate, signed us up for the expert class.

“Wasn’t fair to do anything else,” says Pat. “We aren’t pros, but we aren’t really just sport riders, either.”

Pat, 30, lean and unassuming, is a Ph.D. student in mathematics at the University of Wyoming in Laramie. He’s been bike racing and skateboarding for years. He happens to have a sprained ankle—wrapped in a brace—that won’t heal because he won’t stop riding.

“Ach, you bicycled across Siberia,” Nat tells me. He blows his nose like a trumpet. “You’ll be fine.”

Nat Dyck, 30, six foot four with moose legs, a Laramie-based carpenter and cross-country ski instructor, laconic but glib, is our most experienced rider. He’s been racing for eight years. This will be his fifth 24-hour race. He and Pat were part of a team that rode single-speeds in the 24 Hours of Moab last year. He happens to have the flu.

“I’m betting on broken bones,” says my younger brother Dan, “even with our new überbikes.”

Dan, 38, did a couple of mountain-bike races back when they were still riding penny-farthings. Since then, he’s gotten married and had two kids. He happens to have asthma so bad he breathes like a fat man.

I trail-tested a half-dozen bikes before deciding on the Trek Fuel 100, the Land Rover of bicycles. A ZR9000 alloy frame with OCLV carbon-fiber seat and chainstays; full suspension, a Rock Shox SID Race fork, and Fox Float RC rear shock; Bontrager Lite tubeless tires, Bontrager Lite crank; Shimano XT/XTR nine-speed shifting. The Fuel 100 is so light and responsive, so fast and forgiving, riding it gives you delusions of grandeur. You actually think you can race.

TWENTY-FOUR-HOUR mountain-bike relay racing is the brainchild of Laird Knight, 44, founder of Granny Gear Productions. “I still have a scar on my hip, acquired when I was five,” offers Knight, by way of credentials. “I crashed while riding my bike at night, with one hand holding my handlebar and the other holding a burning stick of wood that I’d pulled from a backyard fire.”

Inspired by his teenage obsession with 24-hour motorcycle races and his stint in the eighties as a National Off-Road Bicycle Association (NORBA) race organizer, Knight staged the inaugural 24 Hours of Canaan in the Allegheny Mountains of West Virginia in 1992. Thirty-six four- and five-person teams competed. That seminal mud bash spawned a booming series that today includes the 24 Hours of Snowshoe, Moab, Tahoe, and, debuting this year, Temecula, California. Organized by Granny Gear with the help of hundreds of volunteers, these events draw upwards of 5,000 riders in more than 1,200 teams; there are also dozens of smaller all-night races across the continent. Indeed, 24-hour relays have become one-day Eco-Challenges for serious mountain bikers: a sadistic combination of solitary suffering and intense teamwork, stamina and sprinting, mental and physical exhaustion—all played out over wildly challenging terrain.

Of course, it’s more than just pain and misery, which becomes apparent the minute we roll into the base area at Northstar-at-Tahoe ski resort: It’s a Woodstock for mountain bikers. There’s rock-and-roll wailing from giant speakers and big white tents and gear booths in the trees along the start of the course. There are vans and RVs and dozens of little tents in the camping area with bike stands sprouting like saplings, guys fiddling with their brakes and lying in the grass drinking beers with their teammates, and women cyclists trick-riding their bikes down steps.

“I think it goes back to the core values of mountain biking,” says Knight of the event’s cultish appeal. “Sportsmanship, camaraderie, and fun. Mountain bikers are such a gritty, hardcore, nonwhining group. They have character, and in dangerous situations they bond together.”

The Tahoe course is one of the most technical in the Granny Gear series: an 11.2-mile loop that starts at 6,330 feet, gains 1,600 feet through open ski slopes and woods, then caroms back down. This year’s 104 teams are organized into more than a dozen classes—from solo pro riders to two-person, four-person, five-person, and all-women squads. Racers ride a lap, pass the baton to the on-deck rider, and then recuperate until it’s their turn to ride again. The team in each category that completes the most laps started between noon on Saturday and noon on Sunday wins goodies from the $15,000 grab bag of gear and prizes; sponsored pro teams vie for a $5,000 purse.

“The relay aspect is critical,” explains Knight. “If you’re racing for yourself, when it gets tough the thought of quitting will go through your mind. You start finding excuses—not enough sleep, sick, whatever. But when you’re part of a team, this never even enters your head. You can’t give up. You can’t let your team down. People never race harder than they do in a 24-hour.”

The riders I talk to tend to agree.

“The camaraderie of 24-hour events reminds me of the old NORBA races,” says Bruce Frazier, 36, captain of Sportin’ Woodys and a veteran of nine 24-hour races. “Now NORBA is mostly competitive professionals, so this is where the funhogs have gone.”

“It’s a big ego-buster,” says his teammate Brian Starkey, 34. “Anybody can ride a two-hour race in daylight. But night riding—that’s good fun.”

“Night riding is what separates this race from all others,” says Chris Schulze, 31, of Top Tube Johnson and da Saddle Sores. “It’s the chance to push yourself to the limit.”

Although men still far outnumber women at these events, there are plenty of strong female competitors.

“Funnnn!” exclaims Stray Voltage’s Barbara Engel, 45, a windsurfer, mara-thoner, and triathlete. “That’s what it’s all about. Sleep? Who needs sleep?”

SHAVED LEGS RIPPED with muscle and tattooed arms and sculpted asses and guys with earlobe plugs, goatees, and Oakleys, and girls with pierced tongues and spiked hair wearing Smiths, and Mick Jagger howling “Start Me Up” through the woods and banners wafting and strings of colorful flags popping. It’s just before noon and a hundred of us are bunched together at the starting line at the base of the mountain, trembling.

For some perverse reason, my teammates have appointed me lead rider.

Now there’s no music, no sound at all. A man is firing a gun in the air in front of us and then I’m running inside a riot of chugging elbows and horse-huffing chests—a 400-yard Le Mans sprint up through the trees and back to the bikes, all of us slipping like clowns in our cycling shoes.

Vaulting into the saddle, I start pumping, only to find that I’m already in such oxygen debt I can hardly stay upright. A rider falls against me and I hear the heart-sickening whoosh of a flat and just keep pedaling, astonished to discover that it was his tire, not mine.

It’s uphill right off the bat. I concentrate on trying to catch the rider in front of me. Then we’re all zipping downhill. Dippy curlicues through rocks and trees, over a bridge, onto the long, grueling ascent. Climbing mountains is not so different whether you’re on foot or on a bike. I grind past one cyclist after another, knowing I’ll need a good lead because they’ll catch me when I start ejecting on the descent.

Miraculously, I’m bucked off only twice descending through the fishhook turns. I come rock-sliding through the gates, and Pat is there yelling and then he’s snatching the baton and I’m fumbling to swipe my radio-frequency time card and Pat swipes his and he’s streaking away and I’m croaking, “Go, go, go!”

I stumble over to the computer tent to check my split: 1:08:45. We’re in seventh place overall, a mere 23 hours of riding remaining.

Walk jelly-legged a quarter-mile uphill to our condo, wheel my bike inside, flop on the couch, and stare dumb-eyed at my battered Trek. Try to eat. Drink four or five gallons of Gatorade. Get the bicycle up on the bike stand and begin tinkering with the messed-up rear derailleur.

My zombie movements amuse Nat and Dan.

“Great ride,” says Nat, and starts hacking.

Thumbs up from Dan as he rolls his steed out the door. He’s on deck.

Minutes click blearily by like seconds. Now Pat is walking in and falls onto the couch and stares at the ceiling.

“Flatted. Can you believe it! Borked my rim but rode it in.”

“That’s the way, Patty!” coughs Nat.

Pat lies there in wasted anguish as I did, attempting to eat and drink. We give Nat high fives as he pushes his bike out of the condo. I drop mine off the stand and Pat puts his up.

Sometime later, Dan comes in with a huge grin and dirt-blackened teeth. “Caught a lot of air,” he exclaims.

A couple of hours fly by and I find myself back at the starting gate. Everybody is smiling and whooping as each rider comes in, and the friendly buzz of it all soaks into me.

Because Nat is sick, I expect to wait, but suddenly he’s blasting in, handing me the baton, and we’re swiping our time cards and before I can even take a full breath, I’m rocketing uphill again.

It’s a good lap: a cracker uphill and only one endo on the descent. Back in the condo, I find Nat has tacked up a page with our lap times. Scribbled at the bottom: drink lots! eat-fix bike-rest-race-repeat. We all have fast second laps, and Big Daddy Meats holds on to seventh place as night arrives.

Mountain-bike racing is by nature gritty and grueling, but having to saddle up a mud-encrusted bike and ride hell-bent for leather in inky blindness is a dicier proposition altogether. Night is when everything falls apart if you don’t have the right lights.

Granny Gear posts testimonials to such nocturnal hardship on :

“Candles are not a reliable backup system; it takes 231 sparklers to do a lap.”

“Anybody can ride hard during the day, but in pitch black and cold, over treacherously technical terrain, everything changes. I vastly underestimated the amount of shit-dialing necessary to ensure sufficient candlepower.”

“Spit forward so you don’t lose sight of the trail.”

“Christmas lights are stylish but eat batteries.”

Nat and Pat had been crash-testing different lighting systems for two years before deciding on Light & Motion, a Monterey, California, company. Their ARC handlebar lights and Cabeza Logic helmet lamps are our salvation. With a backup supply of spare batteries constantly turbocharging in the condo, the 13.5-watt bulbs are so powerful, it’s like riding with motorcycle lights.

More light means safer, faster laps, but at the end of the long, shadowy night, we’re still pretty beat-up. Pat has endoed over his handlebars at 25 miles an hour and re-sprained his bad ankle, and none of us has slept much. We are too tired to sleep; the adrenaline and anticipation gushing through our systems make it impossible to calm down.

DAN RIDES THE SUNRISE lap and rolls in all smiles but wheezing from his asthma.

I ride my fifth lap, starting at 8:20 a.m., only two minutes slower than my first. It’s my cleanest run, and my last. Not one crash. I’m actually learning how to ride during the race.

At the end of each lap, I’ve felt utterly spent. Certain that I went as hard as I could and that I couldn’t do it again for another year. Now I don’t have to.

Pat storms lap number 18, and then Nat takes off for number 19. Big Daddy Meats is still in seventh place. If Nat rides well, we have a chance of getting in one more lap and maybe even placing in the top three of the expert class. But leaving the gate, Nat doesn’t look good; he looks like a cadaver. He’s risen above his illness for four rides, but the fifth might nearly kill him.

His previous laps were in the 1:10 range, so after an hour we start looking for him. Little do we know that at the top of the mountain he has bonked and is lying in the first-aid station, his body limp and shivering.

And yet, after 20 minutes of rest, Nat manages to crawl back onto the saddle and ride out the lap.

When he rolls across the finish line, we’re exultant. It’s 12:40 p.m. and the race is over. We hug just to hold each other up. In the end, we take 13th place out of the 97 teams that finished.

SCABBED LEGS and bruised arms hanging out the windows and some mournful Tammy Wynette tune on the radio and Nevada floating by like a Magritte dream.

“If I come in from a lap and have suffered as much as I possibly could, that means I had a great lap, that means I had a lot of fun…” sighs Nat.

“When you’re having a good race and you get into the groove and you’re focusing, you can sort of transcend the suffering—that’s what’s fun…” says Pat.

“It’s suffering together,” Dan squeaks.

Something happened in the night. We were all out there struggling together, and it was so difficult that the nasty side of competitiveness just melted away. You didn’t know who was ahead or behind; you were just gliding through the cool darkness, pushed onward by the faith of others. Your legs had turned to lead and your lungs were on fire and you were so whipped you wanted to cry, but when dawn finally came, every racer on the mountain had become a member of the same bighearted team.

I want to ask who’s up for Moab, but I’m half asleep. We’re all half asleep, the ghost van carrying us across the desert.