THIS IS A CINDERELLA story. Girl grinds it out as a welder in a large Canadian city. Girl rides a mountain bike extremely well. Girl enters a downhill race and cleans even the pros’ clocks. Girl wins the national championship in her first year of racing and wears the maple leaf jersey at the world championships, where, despite a thrown chain, she has the best run of the Canadian women. But the fairy tale ends there.

michelle dumaresq, transgender athletes, transexual athletes, mountain biking

The fastest girl in Canada used to be a man.

Since 33-year-old Michelle Dumaresq burst onto the scene, in May 2001, winning the novice class at the Bear Mountain race, in Mission, British Columbia, by 2.5 seconds over the fastest female pro, she’s kicked up a dust storm of gender-bending gossip, debate, and polemics. And to spice up the controversy, the very people who ushered her into the sport are the ones clamoring to get her kicked out.

Dumaresq was discovered in 1999, three years after her sex-change operation. She was sticking five- and six-foot drops down the Pink Starfish trail, on Grouse Mountain—on Vancouver’s North Shore, where she’d ridden since she was a boy—when a dozen top women racers arrived to shoot a video. Wowed by her out-of-nowhere moves, they cast Dumaresq in the 2001 bike-chick flick Dirt Divas and encouraged her to race.

Dumaresq was up front about her transsexual history, and her new friends were cool about it—at least until she beat them. Starting in 2001, she rocketed up the Canada Cup Mountain Bike Series from beginner to expert to pro, winning the national series in 2002. In 2003 she dominated again. Though she endoed during the Canadian National Mountain Bike Downhill Championship, held in Whistler last July, Dumaresq still won by a decisive margin of 2.62 seconds.

But her fairy godmothers have been crying foul. In July 2001, bowing to pressure from racers and anxiety over the potential sex storm, the Canadian Cycling Association and the Switzerland-based Union Cycliste Internationale (UCI), which regulates both the Tour de France and World Cup mountain-bike racing, suspended Dumaresq’s license. In April 2002, they reissued it, based on the fact that her official B.C. birth certificate now reads FEMALE, a form of revisionist history at the most personal level.

It was another in a string of international rulings on gender that threaten to turn the sports landscape upside down. As the athletics world wrestles with drugs like steroids and erythropoietin (EPO), the once straightforward concepts of male and female are being challenged by medical science—and by the ambitions of competitors like Michelle Dumaresq.

“Today, we all fight against doping and try to be natural athletes,” says 26-year-old French downhiller Anne-Caroline Chausson, who won her seventh world championship in 2003. “Don’t we open a door for genetically modified athletes—or worse? Why not clone Carl Lewis to race against Marion Jones?”

Chausson is safe for now. Dumaresq has yet to break into the international top ten; she tanked at the 2003 worlds, in Lugano, Switzerland, last September, limping in at 17th with a broken hand. But she remains the most talked-about rider on the circuit. And as she prepares to relocate to train at altitude in Denver, she is bringing her notoriety south.

I asked Chausson what she would do if Dumaresq ever beat her: She said she would quit racing.

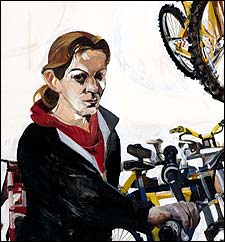

WHEN I FIRST MET Dumaresq, in October 2002, she was punching the clock Flashdance style as a foreman welder at a North Vancouver metal shop. It was quitting time, and her bike was locked inside her 1988 Pathfinder, a rig with more than 185,000 miles on the odometer and a sticker on the hatch reading GIRLS KICK ASS. Her lager-blond hair was pulled into a ponytail, her neck ringed with a silver bike-sprocket necklace, her hands masculine, with thick pipe-fitter fingers. She apologized for not wearing her usual pearl-pink nail polish.

At five foot nine—taller in her boots—Dumaresq is handsome. Her weight fluctuates between 170 and 180 pounds, and she is hockey-goalie solid, her coveralls concealing modest, nearly new breasts. Her jawline is strong, her eyes the fluid green of chainsaw oil. When she smiles, she reveals an elfin gap—she chipped a tooth on a trail called Higher Ground, she’ll tell you, right next to one called Dentist. “Estrogen,” she explained to me, “is not a performance-enhancing drug.”

Dumaresq tossed my bike on top of hers and steered toward the North Shore. “They all know my story,” she said of her fellow metalworkers. “They’re great guys and are cool with it.” Vancouver is a liberal city, but this is a metal shop with heliarc welders and forklifts and truckloads of aluminum tubing. “You can’t cry here; it’s unacceptable,” she added.

Michael Brandon Dumaresq was already a metalworker when he had his gender-reassignment surgery, at age 26. (According to Anne Lawrence, a Seattle physician specializing in transgender issues, since the 1960s an estimated 4,000 people have undergone sex-change surgery in Canada, compared with 15,000 in the U.S.) “I wasn’t gay,” Dumaresq says, “but I’ve known since I was four or five.” Michael’s parents, Art and Judy, had their own accounting business, and he grew up with a younger brother and sister. At seven, he was jumping his banana-seat cruiser off ramps in his driveway, in the hilly Vancouver suburb of Burnaby. At ten, he was trying on his mother’s dresses. At 12, he had a new BMX bike, a plywood quarterpipe in the front yard, and a secret wardrobe of girls’ clothes.

“I had a good time being a boy,” Dumaresq says. “It was lots of fun. I’m just not a boy.” After high school, where he was captain and right wing of his hockey team, Michael took a job at a Burnaby metal shop; at 18, unbeknownst to his family, he walked into his doctor’s office in his work boots. “Here I am,” he said. “I’m a girl. Fix me.”

“They told me to go away,” Dumaresq says. “I explored on my own and basically grew up a bit.” Four years later, Michael went back and began a regimen of the testosterone blocker spironolactone to prepare for surgery. In 1996, on an operating table in Montreal, he became Michelle Jacquelyn Dumaresq. Jacquelyn was what his mother, who was there for the surgery, would have named him had he been a girl.

Some things didn’t change for Dumaresq. Freeriding, for one. The day before, we’d met up with her posse—guys in their thirties and Canadian as bacon and Celine Dion—at Seymour’s, a pub near Mount Seymour, home of such famous trails as Bogeyman and Severed Dick. The party was well under way. Someone filled a pint glass as Paul, the group’s comedic ringleader, razzed Dumaresq: “You know what makes you a real girl? You’re late for everything.” She grinned.

Dumaresq came out to the boys in 2001. There had been rumors on the North Shore, and one night at Seymour’s she told them. “Their reaction,” she says, “was like ‘OK—but we’re still going riding at 4:30, eh?’ ”

Four-thirty, and we were: Dumaresq, myself, and her friend Rob Moysychyn, a machinist dressed in downhill pants and armor, with a long ponytail and an earring. It had rained, and Mount Seymour was a fog-capped world of ferns and moss. Dumaresq danced down the slick trail like a wood pixie, performing wheelie drops off rock faces, high-wire acts along fallen cedars, corrective slides atop wet ladder bridges that rose, twisted, and dipped like melting zippers in a Salvador Dali painting. Her bike, a duct-taped beater with crude dual suspension, compressed hard on each transition—she is expert at the tranny—then released her back to the kinetic lay of the trail.

Here on the North Shore, Dumaresq’s friends don’t seem to give a fart in a gale that she used to be a man; they just want to ride. “Michelle’s my most normal friend,” Rob told me in the bar, après-ride. “I can’t believe that my most grounded friend used to be a guy.”

THERE IS NO SIMPLE indicator that differentiates a born female from a hormonally and surgically altered one. What makes most girls girls is their XX chromosomes. But some women possess XY chromosomes while retaining the physical characteristics of women. And some produce excessive male hormones, a condition known as congenital adrenal hyperplasia that can bring medical problems and athletic benefits. Eight female athletes at the 1996 Olympic Games in Atlanta reportedly “suffered” from CAH—and were approved for competition.

Transgender dustups in sports are older than gender-reassignment surgery, which was pioneered in Copenhagen in 1952. In the 1932 Los Angeles Olympics, Polish sprinter Stella Walsh won a gold medal in the 100-meter race; four years later, in Berlin, she took silver. In 1980, Walsh, by then a naturalized American citizen, was shot and killed in Cleveland in a botched robbery. An autopsy revealed that she was a he. In the 1940s, Czech runner Zdenka Koubkova and German high jumper Dora Ratjen were banned from Olympic competition after doctors found them to be hermaphrodites; both lived the rest of their lives as men. By 1966, a chromosomal scan called the Barr body test took some of the guesswork out of the gender quandary. After a 1968 test determined that Austria’s Erika Schineggar, the women’s world downhill-ski champion, was chromosomally male, she underwent months of surgeries before returning to competition—as Erik.

The most famous transgender athlete is physician and tennis player Renée Richards, formerly Richard Raskin. In 1977, the New York State Supreme Court ruled that Richards could compete as a woman in the U.S. Open. (She lost in the first round, though she reached the doubles finals; ultimately, in 1981, she returned to her medical practice.) Richards, a 70-year-old pediatric ophthalmologist in New York, is not optimistic about Dumaresq’s quest for acceptance. ” ‘Cease and desist,’ I would tell her,” she told a Canadian newspaper in 2002. “It’s very sad for her, but that ultimate satisfaction, she will not get.”

Even today, the transgender jock population largely remains a closeted one: Dumaresq claims to correspond with some 115 undercover, or “stealth,” transgender athletes from all over the world, including a top NCAA women’s basketball player and two women competing at a world-class level in Olympic events. “There are hundreds of athletes out there who have a trans history,” she says, “but they’re not telling anybody because of the implications.”

Still, the rules are changing. Before the 2000 Sydney Games, the International Olympic Committee did away with sex screenings, and the Associated Press reported last November that the IOC would not ban athletes with a transgender history, provided they endure a waiting period following surgery. (IOC medical director Patrick Schamasch later denied the report, saying that no decision had been made.) This winter in the UK, a Gender Recognition Bill was being debated in the House of Lords; if it passes, a man could compete as a woman simply by claiming to be one. But in January 2004, bucking the trend, the International Volleyball Federation announced that while it would no longer conduct gender tests, transgender people would remain ineligible.

The most prevalent argument against transsexual women athletes is that they “grew up male,” with higher levels of hemoglobin and testosterone, and greater lung capacity, heart capacity, and muscle mass. “There is inequality of force between a transgender female and a natural female,” says Dr. Pierre Assalian, psychiatrist-in-chief at the human sexuality unit at Montreal General Hospital. “It’s definitely unfair.”

Less quantifiable attributes also play a part. “Males growing up with testosterone are inevitably more driven, challenging, competitive than women,” says Dr. Oliver Robinow, of Vancouver Hospital’s sex medicine clinic. “This decreases with their change in hormones,” he says, “but does not disappear.”

Michael Dumaresq stood six feet tall and weighed 210 pounds. Although still big, as female downhillers go, Michelle insists she is all woman. Fat has moved to her hips and buttocks, thanks to daily doses of estrogen and progesterone, and she estimates she’s lost 30 percent of her muscle mass. She stops taking hormones four or five days a month to replicate a menstrual cycle. “The first two years are really tough,” she says, “especially the mood swings. Men just don’t understand what it’s like.”

Tell that to the girls. The grumbling began with Michelle’s first race, a May 2001 B.C. Cup event in Mission, in which she beat every pro. The next month, at a B.C. Cup race in Kelowna, she did it again. By her third race, when she spanked every pro but one, the women were livid, including two of her former mentors, 2001 national champion Cassandra Boon and her 2002 successor, Sylvie Allen, now both retired. Several racers filed complaints with Cycling B.C., the provincial arm of the Canadian Cycling Association, which, under the umbrella of the Union Cycliste Internationale, suspended her license.

Over the winter, the UCI reconvened, and in April 2002 reinstated her—as a pro. At Dumaresq’s first race, in Mission, Cassandra Boon handed the race commissioner a petition signed by a dozen riders of both sexes. He denied the protest; Dumaresq won the race.

In an appeal to the UCI dated June 27, 2002, Sylvie Allen wrote, “We are very impressed with her strength, endurance, speed and skill—all quite good as a man, but too suspiciously impressive for a woman. It is our contention that she is not competing on a level playing field.” It was the last major protest. But at the 2002 worlds, in Kaprun, Austria, Dumaresq’s teammates still weren’t speaking to her.

Few racers will discuss Dumaresq on the record today; the attitude, as one Canadian woman rider told me, is “Quit bitching and get off the brakes.” But mountain biking is an obscure cousin in the celebrity sports family of World Cup soccer and Olympic track. Right now, sports bodies are adopting provisional “Don’t ask, don’t tell” gender policies. But when the first transsexual stands on the podium in the Olympic Games, the backlash will make the furor over Dumaresq look like a sandbox squabble.

“PEOPLE THINK YOU just go to the doctor, get your balls cut off, and start racing against the women,” Dumaresq told me the first time we talked. “That’s just not true. I didn’t ask for all this attention. I didn’t want to change the world; I just wanted to race a bicycle.”

Dumaresq seems drastically ambivalent about being a transgender poster child—and who could blame her? Her celebrity comes from having her gonads docked. She tends to shun mainstream media, dodging invites from Connie Chung, Bryant Gumbel, ESPN, and HBO. “I’m not gonna be the next Tonya Harding,” she says. “Forget it.” But she has no problem starring in a Canadian documentary about her life called 100% Woman, which hits festivals in August.

Nearly everywhere she goes, she’s got to shoulder the trans monkey. At one California race last year, I heard a kid bragging that his buddy had parked next to the “shemale.” When the British magazine Dirt ran a story on a 2002 World Cup race at Mont-Saint-Anne, Quebec, its correspondent reported, “The trans-gendered thing that raced finished somewhere in the back.” Dumaresq shrugged when she read it, but I could tell the blow hurt.

She’s got an agent, Rich Vigurs, a 36-year-old Vancouverite with a stable of talent that includes a musher and the two best Hacky Sackers in the world. She has small sponsorships from the Web zine North Shore Mountain Biking and Santa Cruz Bicycles—they gave her two bikes, including a factory-mint V-10 with seven inches of travel up front and ten in back—but, as Vigurs explains, “there’s no money involved in her contracts. I suspect she’s using ketchup packages to make soup.” Still, he insists, she’s raced for only three years. “We really haven’t written the story yet. There’s gonna be some cool possibilities making their way through the pipe.”

“The term I like best is that I’m ‘normalizing’ transgender people in sports,” Dumaresq says. “There is no one else out there. Renée Richards is not a role model.” She is adamant that, unlike Richards, she did not sue for the right to race: She simply asked. Her inspiration, rather, is 32-year-old Missy Giove, who dominated the American downhill scene for close to a decade. Giove is, as Dumaresq admiringly puts it, “a very out, hardcore dyke.” In other words, she doesn’t apologize for who she is.

Dumaresq’s perspective continues to shift. “The title ‘transgender’ itself doesn’t really fit any longer,” she told me last year. “You’re only trans while you’re living in transition. Why am I still calling myself that? Transgender is a medical term. This is not a medical condition. It’s not the same feeling anymore.”

Most notably, she has a girlfriend. Dumaresq has had boyfriends before, including one she met in the supermarket over a bike magazine and who dumped her when she told him her history. Her new love interest also competes, though in a sport closer to the hearts of the Canadian masses: hockey. “Beer-league hockey,” says Dumaresq, who’s been training in her girlfriend’s league, where few people know her story.

There’s still that wistful hope: Maybe the controversy will fade. “In ten years’ time, no one will give a shit,” Dumaresq says. “Somebody had to come forward. It just happened to be me.”

“COMPLETE WORLD DOMINATION.” This is Dumaresq’s goal for 2004. She plans to quit her job manufacturing aluminum boats in Vancouver and move to Denver with her girlfriend. The strategy is to amp up her high-altitude training and start winning on the NORBA and World Cup circuits. Given her history at the worlds—25th at Kaprun, in 2002, 17th at Lugano, in 2003—that’s a long shot. Downhill biking is all about strength, technical virtuosity, and guts. Dumaresq’s got the strength, certainly, and the moxie: She pushes the win-or-crash line; she fell in nearly every 2003 race she entered. Each time, she stubbornly got back on the bike, convincing herself, as much as anyone, that she’s got what it takes.

Domination was the objective of our road trip from Vancouver to Big Bear Lake, California, last May for her first NORBA race. She’d been laid off from her job, so for a few glorious, hungry months, she was finally a full-time professional athlete. Of course, that didn’t stop her from chain-smoking Marlboro Lights or, when we hit L.A., making a beeline for Saddle Ranch, a cowboy-kitsch club on Sunset Boulevard where, two margaritas, a taco platter, and several Newcastles later, she had the best ride of the night on the mechanical bull.

When we pulled into Big Bear in her battered Nissan, it was evident that Dumaresq had arrived in the big leagues. The competition, including Team Luna Chix’s Marla Streb, the 38-year-old U.S. national champion, had set up camp in air-conditioned tractor-trailers outfitted with massage therapists and full-time mechanics. Like the Luna Chix riders, Dumaresq is sponsored by Santa Cruz, but when she approached Rob Roscopp, the company’s founder, he didn’t have time to talk. She was crushed.

The racers, however, were very aware of her presence. Ever-hyper Missy Giove seemed frustrated that Dumaresq was getting so much attention when the best riders were struggling to get any at all. At the same time, Giove is one of her biggest advocates. “She’s so fucking cool; she’s fucking super, super dope,” Giove said between waving at friends and answering her cell phone. “Michelle goes slow right now. If she speeds up, I’ll be totally happy for her. But I might go out and do some more research if she was beating me.”

Dumaresq placed 11th at Big Bear, ten seconds off British racer Fionn Griffiths’s winning pace. In Vancouver, I’d seen her ride things that were exponentially more hairball than this. It occurred to me that back home, Michelle rides like a guy. But nerves started working on her in the California sunshine. This time, she raced like a girl.

Michelle Dumaresq could have done the easy thing—if there is an easy thing for a transgender person in the 21st century—and stayed on the North Shore. To enter into the world of elite racing and excel at it is to huck into seriously sketchy terrain. But there are days when it’s worth it. On Sunday morning, Giove, standing casually on her pedals, coasted by Dumaresq on her way to the start house.

“Hey, girl,” Giove called out through her full-face helmet.

Dumaresq looked up and heyed her back. It was all she needed.