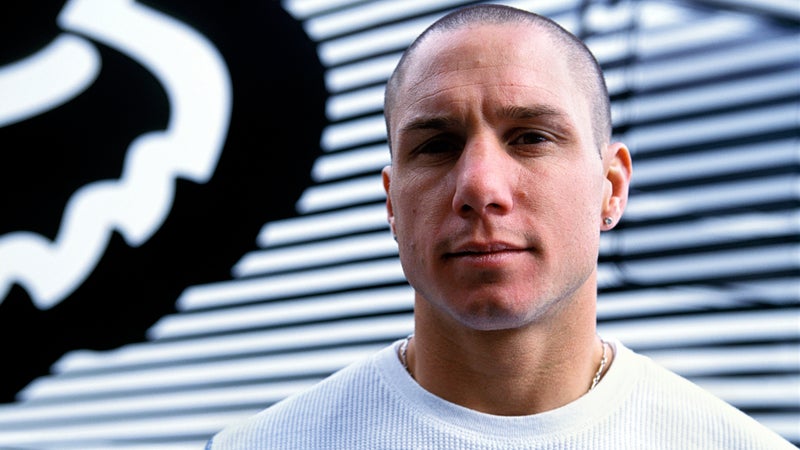

The Last Days of Dave Mirra

In the wake of the X Games star's suicide, friends contemplate the role of repeated head injuries and the psychological toll of retiring from BMX

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

[EditorsŌĆÖ Note: If you are having suicidal thoughts, please contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 1-800-273-8255 (TALK).]

When news broke that Dave Mirra, the most dominant and decorated BMX star in X Games history, had ╠²at age 41╠²in his hometown of Greenville, North Carolina, on February 4, his friends thought it was an Internet hoax. A few even texted Mirra to let him in on the joke.

ŌĆ£ThatŌĆÖs the last guy you would think, because heŌĆÖs stronger than you,ŌĆØ says , a retired motorcycle racer who was MirraŌĆÖs triathlon training partner.

MirraŌĆÖs strength and determination were renowned. Driven and intense, he╠²had won 24 X Games medals in two decades of competition, all but one of them in BMX. (He also won a bronze medal in rallycross in 2008.)╠²But he╠²was humorous and sensitive, a devoted family man to his wife, Lauren, and daughters, Madison, 9, and Mackenzie, 8. Friends say it seemed like he had a lot going for him.

ŌĆ£WeŌĆÖve got a good collage of misfit individuals in our community,ŌĆØ says BMX icon , 43. ŌĆ£He was the one who had it the most together out of all of us.ŌĆØ

Recently, the 41-year-old had surprised friends by telling them he was planning a comeback to the sport: he was building a new vert ramp for training;╠²he presented the Number One Rider Award (NORA Cup) at a September BMX awards ceremony in Las Vegas;╠²and he was making arrangements to attend a reunion of older and╠²retired riders in California in March. ŌĆ£Everyone was getting real excited,ŌĆØ says Hoffman.

In the nearly two weeks╠²since his death, some have╠²speculated that head traumaŌĆöMirra, like many BMX riders, took multiple spills over his careerŌĆömay be╠²to blame for his death.╠²Indeed, those who suffer from Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE), the degenerative brain condition currently plaguing football and other sports that involve significant╠²head trauma,╠²often suffer from depression and exhibit impulsive behavior.╠²NFL Hall of Fame linebacker Junior Seau, who in 2012 shot himself in the chest at age 43, had CTE; Greenville Mayor Allen Thomas, who was friends with Mirra, suggested that he might have had it as well. (UPDATE:╠²In late May, Mirra's widow, Lauren, announced that a study of her late husband's brain . The study was coordinated by Dr. Lili-Naz Hazrati, a neuropathologist at the University of Toronto, and the Canadian Concussion Centre. The diagnosis was confirmed by neuropathologists in the U.S. and abroad, according to a release by a Mirra family spokesperson.)

But in more than a half-dozen interviews with friends, colleagues, competitors, and authorities, it became clear Mirra had lost direction,╠²whatever else he may have been suffering from. When he ended his BMX career in 2010, at age 35, he refocused his passion and commitment first on rally car racing, then on a budding interest in triathlons. But several setbacks last year caused his commitment to waver. Famous for his energy and work ethic, Mirra complained of fatigue and confessed that he was feeling down. Alarmed, some friends talked and said they needed to keep an eye on him.

Born in 1974 in Chittenango, New York, near Syracuse, Mirra stormed the BMX scene in 1987 when he was 13. (Even at that young age, he was already sponsored by Haro Bikes.) After dominating╠²riders in his age group with a repertoire of the most advanced tricks, performed with uncanny consistency, he turned pro at 17.

ŌĆ£He had a young cocky persona, but it was done with humor,ŌĆØ recalls , 49,╠²who was an established pro when Mirra first arrived on the scene.

At the time, Mat╠²Hoffman was the dominant competitive rider. When he first saw Mirra, he realized that reign was over. ŌĆ£I was like, ŌĆśI better start getting used to getting second,ŌĆÖŌĆØ he says. ŌĆ£A lot of us specialize in different disciplines in the sport, but Dave could do all of it. He could do big, burly tricks, then lay down the most beautiful finesse on the ground.ŌĆØ

When [Hoffman]╠²first saw Mirra, he realized that reign was over. ŌĆ£I was like, ŌĆśI better start getting used to getting second,ŌĆÖŌĆØ he says.

MirraŌĆÖs career nearly ended just as it was taking off, though. In 1993, when he was 19, he was hit by a drunk driver after leaving a club in Syracuse, fracturing his skull, dislocating his shoulder, and leaving him with a blood clot on his brain. He spent six months off his bike while recovering. In 1995 Mirra had his spleen removed following a slam at an event in Dallas. The injuries didnŌĆÖt stall his ascent in the sport, though. When ESPN (then known as the Extreme Games), in Providence, Rhode Island, in 1995, Mirra capitalized on the increased visibility and commercial opportunities for what had been a fringe sport.

ŌĆ£He was exactly what we were looking for in terms of a marketing message about the X Games,ŌĆØ says Chris Stiepock, who spent nearly 20 years working on the X Games for ESPN, and now works at NBC Sports. ŌĆ£He was clean-cut. He was well-spoken. He was obviously very athletic, and he took it seriously.ŌĆØ

With the retirement of skateboarder Tony Hawk in 1999, Mirra emerged as the face of the X Games franchise. In 2000, he became the first BMX rider to in competition, and was soon featured in ads for Burger King and sponsored by Slim Jim and DC Shoe Co., which designed╠²a signature line of shoes for Mirra. His name even graced a video game franchise by Acclaim Entertainment.

Mirra once held the record for most X Games medals by any athlete╠²with 24, including 14 golds (which was broken by skateboarder Bob Bunrquist in 2013). He won the Park and Vert competitions from 1997 to╠²1999. ŌĆ£Because he was so great, he was his worst critic,ŌĆØ Hoffman says. ŌĆ£Everybody else is praising how amazing he is, and in his mind heŌĆÖs like that could be better and IŌĆÖm going to make it better, and he did.ŌĆØ

He earned at least one BMX medal every year from 1995 until 2009, except for 2006. That was the year, while practicing on the Park course at the X Games in Los Angeles, Mirra fell 16 feet from a ramp onto his head, in what he described as his worst crash ever. He spent months recovering after a trip to the ICU.╠²Although he returned to competition and won three more medals, his era of dominance was over. Mirra would never win gold again. In 2010, he missed the X Games while recovering from bacterial meningitis, which his wife, Lauren, said had nearly killed him. (Without a spleen, he was more susceptible to infection.)

He had also begun showing psychological effects╠²from all of his injuries.

ŌĆ£ThereŌĆÖs this term called pop-out-itis, whenever youŌĆÖre going fast at a ramp and your brain switches where you canŌĆÖt do this, and you jump out to the deck. He did that a couple times, and was like, ŌĆśMan IŌĆÖm getting this pop-out-itis,ŌĆÖŌĆØ says Hoffman.

In a for X Games.com, Mirra explained his mindset leading to retirement. ŌĆ£For me, it came down to risk versus reward,ŌĆØ he explained. ŌĆ£My mental stance on it was that I always loved to progress, first and foremost. It was never going to be that fun for me to go on riding on a plateau level and not keep progressing, but by the same token, I got to a point where I really couldnŌĆÖt take getting injured anymore in the name of progression.ŌĆØ

Rather than show up and fail to place, Mirra simply walked away from his bike. ŌĆ£I donŌĆÖt really miss it,ŌĆØ he said in the interview.

BMX fans were upset about the abrupt retirement.╠²,╠²a BMX medalist╠²who retired in 2010,╠²remembers talking to╠²Mirra╠²about being the object of public ridicule.╠²ŌĆ£People would talk shit about us [on social media and online] and it would hurt our feelings,ŌĆØ╠²Lavin╠²says. ŌĆ£He was very, very, very sensitive, almost to a fault. He would say, ŌĆśOh,╠²Lavin, I donŌĆÖt give a shit.ŌĆÖŌĆØ But when pressed,╠²Mirra╠²would admit that the criticism stung.

There comes a reckoning for every athlete when his skills diminish and his competitive career begins to wane. Faced with life-altering, disorienting decisions, heŌĆÖs dogged by questions about himself: Who am I now? And where do I go from here?

ŌĆ£It is a big comedown,ŌĆØ says Lavin, whose career ended after he crashed while competing in a 2010 BMX dirt jumping event, sustained bleeding on his brain, and was placed in a medically-induced coma. ŌĆ£You see it with everybody, from baseball to football players and everybody else. TheyŌĆÖre not in the pinnacle of their career anymore. ItŌĆÖs a hard pill to swallow.ŌĆØ

Retirement didnŌĆÖt sit well with Mirra either, who friends say felt adrift without someplace to channel his inner drive. ŌĆ£He was the most fierce competitor IŌĆÖve ever known,ŌĆØ says Katie Moses Swope, MirraŌĆÖs publicist. As his BMX career wound down, Mirra tried to direct his substantial energies into another X Games sport: rally car racing.╠²At first, he was successful.╠²He won a bronze medal in the event at the 2008 X Games, and joined the Subaru racing team. But he struggled to continue that╠²success. In 2013, he was bounced from Subaru, and joined the Mini team, where he posted fast qualifying times, but was dogged by wrecks and false starts.

Then, in 2012, Mirra╠²watched a friend from Syracuse, Eric Hinman, compete in an Ironman in Lake Placid, New York. He recognized something that was both familiar (he had, after all, made a career riding a bike) and presented a new challenge. Mirra hired a coach and devoted himself to triathlon training in 2012.

ŌĆ£I saw his training, his intense dedication, and decided I needed something to fill a void,ŌĆØ Mirra about HinmanŌĆÖs example. In March 2013 he competed at the 70.3-mile Bay Shore Triathlon, in Long Beach, California, placing fourth. ŌĆ£When I called my wife from the finish line I was almost in tears I felt so good,ŌĆØ he .

Mirra that he liked the heart and hard work required to get a good result. ŌĆ£IŌĆÖve never been a runner,ŌĆØ he said. ŌĆ£IŌĆÖve never been a swimmer and I never spent much time on a road bike, but IŌĆÖm willing to put the work in and IŌĆÖve got some big personal goals for next year.ŌĆØ

He competed in the Raleigh Ironman 70.3 but was bogged down with the swim and run. He struggled to finish races in 2013 and switched coaches to improve his swimming.╠²In September of that year,╠²he qualified for the 2014╠²70.3 World Championship in╠²Mont-Tremblant,╠²Quebec.╠²He finished in 4:36, good for 79th out of more than 300 in his age group.

As he trained, he began talking to Ben Bostrom, a pro motorcycle rider╠²who he had met╠²on the 2014╠², a 3,000-mile road bike race from the Pacific coast to the Atlantic.╠²When one of Bostrom's teammates got sick in the race and Bostrom had to log more miles,╠²Mirra offered to ride with Bostrom, even though Mirra had just completed his own ride. Their friendship was cemented in the grind of long days on the bike. The two made a pact to qualify for the 2015 Ironman World Championship, in Kona, Hawaii.

ŌĆ£I definitely didnŌĆÖt have his work ethic,ŌĆØ says Bostrom. When other riders turned their bikes over to mechanics while they ate╠²dinner and rested, Mirra would set to work on his own bike. ŌĆ£IŌĆÖve never seen anybody put so much into it.ŌĆØ

Mirra switched coaches again in preparation for a full IronmanŌĆÖs longer distances (140.6 miles instead of the 70.3-mile half-Ironmans). ŌĆ£This is what scares me about the full distance,ŌĆØ Mirra told Triathlon Canada.╠²ŌĆ£I just change as a person. ItŌĆÖs like a first relationship in high school, where not a second goes by in the day when youŌĆÖre not thinking about the person.ŌĆØ

Ironman officials had previously offered Mirra a ŌĆ£mediaŌĆØ qualifying exemption for the world championship. The same offer had been made to╠²╠²Olympic champion speed skater Apolo Ohno and retired Pittsburgh Steelers receiver Hines Ward, but╠²Mirra╠²turned it down. He wanted to earn his way.

Because both Bostrom and Mirra╠²were 41, and every event has a limit on the number of qualifying slots for Kona in each age group, they╠²registered for separate competitions last year to avoid being in direct competition for a slot. Bostrom competed in Ironman Canada in Whistler, British Columbia, while Mirra signed up for Ironman Lake Placid, both held╠²July 26.

ŌĆ£It is a big comedown,ŌĆØ says T.J. Lavin. ŌĆ£You see it with everybody, from baseball to football players and everybody else. TheyŌĆÖre not in the pinnacle of their career anymore. ItŌĆÖs a hard pill to swallow.ŌĆØ

Bostrom battled the conditionsŌĆöbecoming nearly hypothermic. While he crossed the finish line, he did not qualify. Meanwhile, Mirra struggled on the run, finishing in 11 hours, 54 seconds, good for 24th in his age group but not good enough for Kona. After the race, the tone of╠²his Instagram posts was overwhelmingly positive and triumphant. Yet Bostrom heard something else when they caught up by phone. ŌĆ£I could hear the letdown in his voice,ŌĆØ he says, ŌĆ£trying to figure out why he failed. He analyzed it. He broke it down.ŌĆØ

Bostrum╠²said they could train together and try again in 2016. He said they would be stronger. At first,╠²Mirra seemed to agree.╠²In the coming days, however, he╠²changed his mindŌĆöhe wanted to attempt to earn a world championship╠²slot at Ironman Mont-Tremblant on August 16, less than three weeks after the╠²Lake Placid race. Rest and recovery from an Ironman is measured in months, not weeks. The psychological and physiological toll is depleting. Mirra disregarded that and went at another competition full bore. He completed the 2.4-mile swim in a personal bestŌĆöone hour, seven minutesŌĆöbut his legs simply stopped turning during the bike ride, and he did not finish. ŌĆ£Mirra went back for another go in just two weeks,ŌĆØ Bostrom says, ŌĆ£which the body canŌĆÖt do.ŌĆØ

On September 17, Mirra was in Las VegasŌĆöwhere both Bostrom and Lavin liveŌĆöto attend the Number One Rider Award (NORA Cup) ceremony, an annual gathering of the tribe held by Ride BMX magazine. ŌĆ£No one had seen him in a while because he had been in his other worlds,ŌĆØ Hoffman says. ŌĆ£Everybody was so ecstatic that Dave was there. It was more like a Dave reunion than an awards show.ŌĆØ

Mirra stayed at LavinŌĆÖs house that week, and the two of them planned to join Bostrom to do some time trials. (Lavin is╠²a╠²triathlon competitor as well.) But the intense training never materialized: they rode bikes only╠²once, and swam once in BostromŌĆÖs pool. ŌĆ£It wasnŌĆÖt the guy I was used to hearing push me,ŌĆØ says Bostrom. ŌĆ£Instead I was pushing him to try to train.ŌĆØ

One night Mirra replied by text. IŌĆÖm sorry, Bostrom recalls him saying. I donŌĆÖt mean to let you down. I just feel really low. I guess itŌĆÖs just midlife crisis. The next day he sent another text saying he needed to get home to his girls. ŌĆ£He left just like that,ŌĆØ says Bostrom.

Lavin had his own cause for concern. A teetotaler, he had observed Mirra drinking more than usual that week. One night he sat Mirra down at a Starbucks at 4:30 a.m. ŌĆ£I was like, ŌĆśDave, youŌĆÖve developed some bad habits and itŌĆÖs not a good lookŌĆÖ,ŌĆØ Lavin recalls. ŌĆ£I wanted him to focus on being a great dad and a good person.ŌĆØ

One night Mirra replied by text. ŌĆ£IŌĆÖm sorry,ŌĆØ Ben Bostrom recalls him saying. ŌĆ£I donŌĆÖt mean to let you down. I just feel really low. I guess itŌĆÖs just midlife crisis.ŌĆØ

The day Mirra left Las Vegas, Lavin phoned Bostrom. ŌĆ£WeŌĆÖve got to watch that guy,ŌĆØ he said. ŌĆ£HeŌĆÖs pretty down.ŌĆØ

Both men periodically called to check up on Mirra. ŌĆ£IŌĆÖm just tired, man,ŌĆØ he told Bostrom on one such phone call. ŌĆ£My body is just tired.ŌĆØ

On the afternoon of Thursday, February╠²4, Mirra was at home in Greenville╠²visiting a friend across town. ŌĆ£They were making plans to go out again,ŌĆØ Greenville Police Chief Mark Holtzman would explain one day later. Around 4 p.m., Mirra left his friendŌĆÖs house, climbed into the cab of his truck, which was parked in the driveway, and shot himself╠²with a handgun. He left no suicide note, but Holtzman said a police investigation concluded that╠²ŌĆ£he had been struggling in some areas like [depression].ŌĆØ

After MirraŌĆÖs suicide, Bostrom got a call from Jimmie Johnson, the six-time Sprint Cup series champion, and another fitness fanatic. ŌĆ£Have you looked into head injury?ŌĆØ he asked. Bostrom hadnŌĆÖt, though he had sustained a major blow in a motorcycle crash at Daytona International Speedway. Johnson explained that a football player friend of his had gone just like Mirra. ŌĆ£You guys should look out for each other,ŌĆØ he said.

To Lavin,╠²CTE sounded plausible. ŌĆ£ThereŌĆÖs no other explanation for why a guy with everything would do something like that,ŌĆØ he said.

Others were skeptical. Hoffman, who estimates heŌĆÖs had at least 100 concussions, was among them.╠²ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs so╠²easy╠²to go, ŌĆśOK, thatŌĆÖs whatŌĆÖs wrong,ŌĆÖŌĆØ╠²he says about CTE.╠²ŌĆ£I donŌĆÖt think itŌĆÖs so simple.ŌĆØ

Many are baffled that a man with so much to look forward toŌĆöhis wife and daughters, a return to BMXŌĆöwould give that up.╠²Yet some friends wonder if his failure to reach new goals in new sports may have contributed to that moment. They knew that Mirra's success was due to an abiding drive to achieve more. At 41 years old, though, his days of performing at the highest level╠²were dwindling.╠²Hoffman was even wary about╠²Mirra's╠²return to BMX, though he says the two never discussed it. Hoffman didn't want to add to any pressure Mirra had already put on himself.╠²

“The greatest athletes and artists are their worst critics,ŌĆØ Hoffman says. ŌĆ£The trick is being your worst critic while not driving yourself crazy.ŌĆØ╠²