The Tour de France is no ordinary bike race.

Riders dream about it, Netflix makes shows about it, and the winner’s yellow jersey is one of the most famous prizes in international sports.

And just like the Tour de France is a ride like no other, the way in which cyclists train for for the race is different than how they prepare for other big events like Paris-Roubaix or the Olympics. Cyclists getting ready to ride a grand tour—a three-week race—follow a master preparation plan that relies heavily on high-altitude camps, targeted racing, and rest in order to hit their respective physical peak. Experts from various corners of sports science guide these riders and teams for months before the event. The goal is to help a top rider, like last year’s winner Jonas Vingegaard of Team Jumbo-Visma, unlock his physical potential during the race.

“Jonas knew his Tour de France training schedule nine months ago,” Jumbo-Visma head of performance Mathieu Heijboer told ���ϳԹ��� on the eve of the 2023 Tour. “Not the exact sessions, but he knew almost exactly would he’d be racing, resting, training to peak. In some cases he even had an idea what he’d be eating.”

Also read:

We recently spoke to directors and coaches from several Tour de France squads to better understand the modern philosophies and training structures that riders follow before the race. They shed light on some of the most fundamental—and the most finicky—elements of a rider’s Tour training plan.

A High-Altitude Arms Race

One of the most labor-intensive and expensive elements of any team’s Tour preparation comes in the planning and execution of a series of training camps performed at high altitude. These camps allow riders to pedal long and steady miles at low intensities early in the season to build their aerobic base prior to the season’s start in late February. They typically last anywhere from two weeks to a month.

Once seen as a luxury for only the richest teams, these camps, which are often held at elevations above 6,000 feet, have become a required cornerstone for most Tour teams and riders. The age-old philosophy of “living high and training low” helps a rider boost blood cell count and max out the oxygen-carrying capacity.

“We’ve been going to altitude a very long time, and I think we’re close to finding a winning formula every time. And we’ve seen it works for Jonas,” Heijboer said. “To be able to get to perform at the highest level in the races we want, we can come very close with altitude training.”

But there’s a hurdle standing between teams and high-altitude destinations. In January and February, the mountain resorts in the Alps and Pyrenees are socked in with snow. So, teams must look to warmer climates to find training destinations. In recent years, many have booked rooms at empty ski lodges in southern Spain’s Sierra Nevada mountains, or on the slops of 12,188-foot Mount Teide, a soaring volcano on the Canary Islands. But there’s another problem: there are often more riders than available rooms at these destinations. During January and February, perhaps a half dozen squads will decamp to these destinations, so squads must book their rooms sometimes multiple years in advance.

The race for rooms at thin air shows how training at altitude is becoming more important with every passing season.

Get altitude training right and riders could boost threshold power by as much as five percent. Get it wrong, they might be burned out and used up before they even see the pre-Tour presentation ceremony.

“We know that altitude works, that’s why we put more and more focus there. But you have to do it right to make it really work,” Quick-Step coach Vasilis Anastopoulos said. “We’re learning more and more how to do it.”

Just like any training program, an altitude framework requires a slow steady accumulation of gain. So, riders don’t just do one camp at altitude, but rather multiple stops before the Tour. During a typical season, a Tour de France star rider may complete three or even four high-altitude camps prior to the race. They structure these camps between blocks of racing at one-day races, like Belgium’s Liège-Bastogne-Liège, or one-week races like France’s Paris-Nice.

“You need repeat altitude camps for the ideal effect. A camp earlier in the season can act as a primer and make the adaptation in the second camp more effective,” UAE Emirates performance co-ordinator Jeroen Swart told ���ϳԹ���. “But that has to be countered with the fatigue that can happen from being at altitude for too long.”

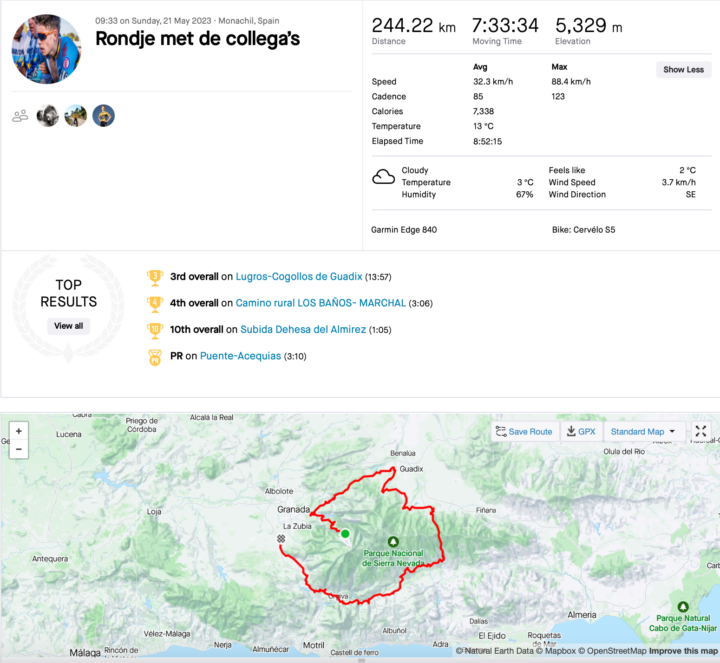

Some riders continue the steady and long training rides throughout the season. Scroll through any Tour rider’s Strava account and you will see just how much time is invested into building out the low-intensity foundations. Belgian star Wout van Aert’s feed from May shows repeat seven-hour rides out of the Sierra Nevada as he stacks up training weeks of up to 30 hours. American rider Matteo Jorgenson, French star Romain Bardet, and British rider Fred Wright also regularly pedal 400 or so miles per week before the Tour.

Races That Strengthen Legs

You can’t just train your way to the Tour de France—riders must also race before starting the big event. The back-to-back training weeks at altitude help riders build an endurance base required to survive the three-week Tour de France. But the races in the lead up to the Tour help these riders become accustomed to the ebb and flow of competition.

Major one-week stage races like France’s Paris-Nice, held in March, and France’s Critérium du Dauphiné and Switzlerland’s Tour de Suisse (both held in June) are important preparation races for any rider hoping to be competitive at the Tour.

“The only thing you cannot mimic at altitude is the nervousness in the peloton and the accelerations, etc,” Jumbo-Visma trainer Heijboer said. “That’s almost becoming the main reason we send riders to many of the races. Before, like when I was a pro, those races would be the training.”

Weeklong races offer big saddle time, a dose of intensity, and for some riders, a chance at grabbing a confidence-boosting win. Plus, riders can master important racing skills like navigating the peloton and avoiding crashes that cannot be reproduced in training. This year, defending Tour champ Vingegaard has used these races to build his form and boost his confidence. In April he won Spain’s Tour of the Basque Country, a mountainous six-day stage race. Then in June, he won two stages and the overall at the Critérium du Dauphiné in France.

But after the races and some short rest days, riders like Vingegaard again head for the thin air for their final pre-Tour training sessions at altitude. Vingegaard and his Jumbo-Visma teammates will spend the final days before the2023 Tour at the ski resort Tignes in the French Alps. Two-time Tour winnner Tadej Pogačar and his UAE-Team Emirates squad will be a few valleys away in the Italian resort village of Sestriere.

“Training at altitude tends to boost hemoglobin around two or two and a half weeks. So it means that we do have to do a final ‘top-up’ camp of volume and intensity in the weeks prior to the Tour,” Swart said. “We work the racing schedule around that concept.”

No Such Thing as a Taper

As Swart alluded to above, a Tour de France rider’s training volume doesn’t drop, even the week before rollout. They do not taper off, but rather keep the miles big. Riders preparing for one-day events like the Olympics or the world championships often drop their training loads significantly prior to the race. But for the Tour, the mileage stays high.

“We never drop out the volume sessions, even near the Tour they stay important,” Swart continued. “Think about it. Those last sessions before the Tour, they’re still a month from the third week of the race, and that’s typically where the most important stages are. You need to keep volume high the whole way, so the base is there for the final stages of racing.”

Marathoners or riders aiming at Olympic or world championship medals typically progress through a seven-to-10-day taper in advance of their A-race. Volume is decreased but intensity maintained, meaning athletes toe the start line fresh and at their peak. Not so for most Tour riders. The only exception are the sprinters who target stage wins early in the race. They may drop the volume by a few miles to rest their legs.

“In an endurance training program, volume is something you will never take out. We make sure they’re recovered and have the energy reserves, but in some stages, the low intensity in the peloton means there can be a slight ‘detraining.’ Limiting a taper means you maintain the training adaptations,” UAE’s Swart said.

A Three-Week Peak

In recent years, organizers of the Tour de France and other three-week grand tours have shifted the racing format. This has forced riders to try and maintain a physical peak for the entire race.

In past generations, the Tour often opened with a steady first week of flat stages that catered to the sprinters. GC stars like Vingegaard could stay hidden in the peloton and use the flat stages to build some final aerobic fitness for the mountainous stages in the second and third weeks. British rider Chris Froome, winner of four Tours de France, followed this exact framework to win the 2018 Giro d’Italia. Froome started race still hunting for fitness and used the opening week to build his strength before attacking in the final week to take the overall victory.

That doesn’t work anymore. In recent years, Tour organizers have included mountains and summit finishes in week one as a way to test the GC stars early. The 2023 Tour de France is no exception.

This year the Tour has nine consecutive stages before the first rest day on July 10. Of those nine stages, three are classified as “hilly” routes and three others are categorized as “mountainous.” Stage nine finishes with the steep climb to Puy De Dôme in the Pyrenees. Vingegaard and Pogačar will need to be fit early if they want to compete.

“This year’s course makes planning the training and peak more complicated,” Jumbo-Visma’s Heijboer said. “They need you need to be at a very high level from the beginning, all through to the end.”

Despite all of this planning and preparation, trainers and riders still say that preparing for the Tour includes plenty of luck and chance. Each rider’s body reacts differently to training programs, and there are unpredictable factors like sickness, crashes, and motivation that can also impact a rider’s progress in the Tour. So, while these teams may spend big bucks trying to get every detail right, the coaches know that the Tour is unpredictable and surprising—that’s what makes it so fun to follow.

”But there’s only so much we can do based on our own knowledge and experience of the rider,” Swart said. “Training athletes is not an exact science. There’s a lot of nuance. There are often unpredictable factors that you can’t measure.”