LINING UP at the start of April’s six-day, 650-mile Tour de Georgia was an all-star cast of American cyclists: Lance, Bobby Julich, Levi Leipheimer, and Floyd Landis, among others. Buried in the pack somewhere behind them was America’s next generation of Tour contenders, one of whom was Craig Lewis, a shy, soft-spoken 20-year-old South Carolinian riding for the TIAA-CREF squad. Looking at Lewis’s whippetlike five-foot-ten, 143-pound frame, few would peg him as the next Lance Armstrong. But Jonathan Vaughters, the team’s director and himself a four-time Tour rider, calls him just that, and he isn’t kidding.

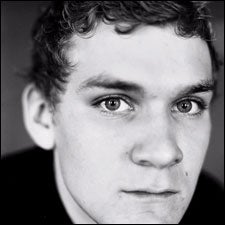

Craig Lewis

Craig Lewis

Craig LewisCraig Lewis

GEN NEXT: Get used to seeing this face. Ascendant cycling phenom Craig Lewis may be Lance’s heir.

GEN NEXT: Get used to seeing this face. Ascendant cycling phenom Craig Lewis may be Lance’s heir.

“Of all the 20-year-olds in America,” Vaughters says, “Craig has the best chance to win the Tour de France.”

What’s caught his eye is Lewis’s phenomenal power-to-weight ratio and the singular fact that, in the Spartanburg native’s first two years of bike racing, he progressed from a rookie in the Junior class, battling other 16-year-olds, to a pro racer taking on the top cyclists in the world. As Vaughters puts it, “He’s the only kid who has Lance’s kind of motor.”

That motor has brought Lewis recognition, but it’s also put him in the way of catastrophe. During the 18-mile time trial in the 2004 Tour de Georgia, Lewis was cranking downhill at 40 miles per hour when a 65-year-old retiree gunned an SUV directly into his path. Lewis never had a chance to put on the brakes. At the time of the crash, his pace had him finishing in the top ten. But instead of sprinting for the last mile and a half, he was being rushed to the hospital with both of his lungs punctured, a fractured scapula, collarbone, tibia, wrist, and skull, 14 cracked ribs, a broken nose and vertebra, plus a busted jaw. When Lewis regained consciousness several hours later, he motioned for a pen and paper and wrote, WHEN RIDE?

Eight weeks later was his answer. And in an uncanny parallel to Armstrong’s assertion that, compared with the pain of chemo, riding a bike is nothing, Lewis returned with a new tolerance for suffering. “My pain threshold is now ten times higher than it was before the accident,” he says. “Attacking a big climb, I can go all out forever. I’ve broken beyond all my limits.”

Nowhere was this new grit more evident than in his off-season training rides in South Carolina with Armstrong’s longtime teammate George Hincapie, who has made Lewis his protégé. “He looked like a really talented rider, loved to ride his bike,” says Hincapie, “and he didn’t mind doing hard work, so we got along right away.”

This past winter saw a big jump in Lewis’s power, when for the first time he beat Hincapie, one of the U.S.’s premier speedsters, in a couple of training sprints. Says Hincapie, “Lewis is definitely capable of racing in Europe as a pro.”

Four years ago, nobody would’ve predicted this. Lewis was a straight-A high school junior from the rural South with a predilection for the music of Linkin Park and 50 Cent—and no interest in sports. “He’d become a couch potato,” says his mother, Judy Lewis, a supervisor for Spartanburg’s Department of Social Services. But then Lewis caught a mountain-bike race on OLN early in the summer of 2000. “I knew right away that I wanted to do that professionally,” says Lewis.

Within a month, he’d bought a bike and was charging around the trails surrounding his home in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains. Two months after his inaugural turn of the pedals, he entered and won his first mountain-bike race, finishing five minutes ahead of the pack. Then, to train for off-road racing, Lewis bought a Giant TCR 2 aluminum road bike and later notched a top-20 finish in his very first road race.

Lewis’s big break, which shifted his focus to road racing, came in September 2001. While competing against elite locals in Greenville, South Carolina, he caught the eye of Hincapie’s brother, Rich, president of Hincapie Sportswear, a local race promoter, and team director of the amateur Fairway-Subaru racing team. Rich brought Lewis onto the Fairway-Subaru squad—then mostly made up of top veteran riders in their thirties—and quickly upgraded his racing license so he could face off against pros. “He weighed 115 pounds soaking wet,” says Rich, “yet he kept up with the best pros in the region.”

Lewis also brought a level of sophistication and maturity that shocked both Hincapie brothers. “He was very meticulous with his training and preparation and nutrition,” says Rich. “That’s expected of an experienced vet, but when you’re a 16-year-old kid going to high school—it was something we’d never seen before.”

IN THIS, HIS SECOND year of competition against the some of the planet’s best riders, Lewis has made it as a bike racer, albeit one earning just $800 a month as a member of TIAA-CREF, a development team composed of riders aged 23 and younger. And while his middling 54th-place finish in this year’s Tour de Georgia is a reminder that Lewis is still defined mostly by that elusive word potential, seasoned observers and participants in the pro peloton, such as Vaughters and Hincapie, say that’s all he needs right now.

The reason? In physiological terms, the 20-year-old is where Lance Armstrong was at roughly the same age. In 1993, tests of a 21-year-old Armstrong after he won the World Championship road race showed him churning out 5.5 watts per kilogram of body weight over a sustained period. Last winter, when Lewis performed the same test, he pumped out 356 watts, which when broken down per kilo of body weight matches Lance’s output of 12 years ago. And as Lewis matures and peaks in the next decade, he could see a 20 percent jump in power—the difference between a podium finish and ending up at the back of the pack.

Despite Vaughters’s and Hincapie’s excitement over Lewis’s biology, both know that the key to his success is not to rush him. After all, most pros now peak in their late twenties to early thirties.

“He’ll be ready to ride the Tour for the first time when he’s 25 or 26,” Vaughters explains. “Until then he’ll probably need two years of racing in the States and a few select international competitions. Then he’ll be ready to sign with a ProTour team and either sink or swim.”

“Our data show that it’s up to 45 watts harder just to ride at the European level,” says Steve Johnson, director of athletics for USA Cycling, the governing body for cycling in the U.S. “To ride at that level, you have to be exposed to that level of competition for a long period of time. If you can get accustomed to that pace—plus the crashes and the cutthroat tactics—then you can ride anytime, anywhere, and with anybody.”

If all goes as planned, Lewis will be getting a taste of Euro power in June, when he’s slated to compete in the four-day Route du Sud, a brutal race through the French and Spanish Pyrenees. “A lot of the top teams will use this as a final preparation for the Tour,” says Vaughters. “Just finishing it will be a big step in the right direction.”

Ultimately, however, success will come down to Lewis’s drive to dominate, and, according to Vaughters, he’s got it. “Craig wants to win in Europe, and he knows that racing there’s not going to be fun, but he doesn’t care. He’s going to make it anyway.”