Ed. Note: With a installed at the UCI, a fresh crop of Lance Armstrong-themed and on the way, and pundits continuing to ask about (and to) the pro peloton, drugs in cycling remain hotly discussed. Recently, much attention has been directed at the biological passport—the screening system for athletes, created in 2008 and intended to dope-proof pro and Olympic sports. Critics contend it still doesn’t go far enough. Anti-doping crusaders, on the other hand, argue in support of the bio passport. Case in point: The controversial performance by American Chris Horner, who, in September, became the first American to win the Vuelta, and, at age 41, the oldest rider in history to win one of Europe’s prestigious grand tours.

Read More:

What is the Biological Passport?On Sept. 25, in what appeared to be a good-faith effort at transparency, Horner released his bio passport data to the public. But the move seemed to raise more flags than it lowered. We checked in with Michael Puchowicz M.D., a sports medicine physician for the Arizona State University Health Services and author of the blog, to see how Horner’s bio passport numbers hold up under anlaysis. Conclusion: Not very well. Here, Puchowicz explains why:

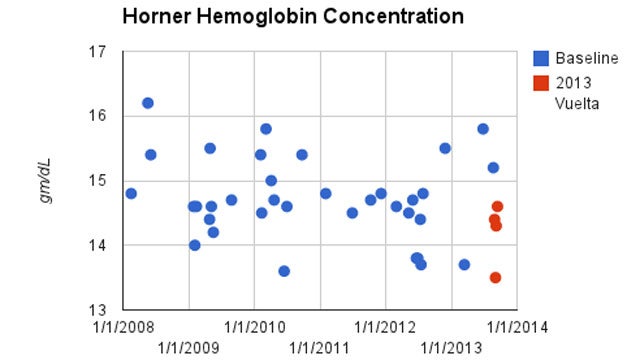

Chris Horner’s blood values during the Vuelta better fit with the patterns that anti-doping authorities look for as signs of cheating. The first element of Horner’s bio passport that raises concern is the hemoglobin concentration. Hemoglobin is the oxygen-carrying protein inside red blood cells. In endurance sports, athletes seeking an advantage have been known to use EPO or blood transfusion to increase their total hemoglobin. The biological passport tracks the hemoglobin concentration as an indirect marker of EPO use or blood transfusion. Anytime that the hemoglobin concentration is higher than expect it is an indication that EPO or a blood transfusion may have been used.

Above is Horner’s complete hemoglobin concentration data from his published bio passport, spanning from early 2008 to September 2013. The Vuelta values are highlighted in red.

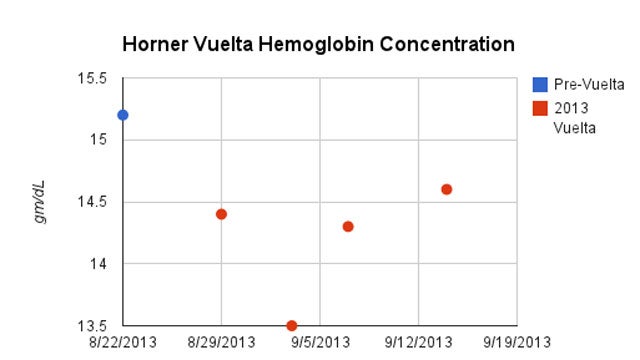

Above is the pre-Veulta and Vuelta values plotted to better visualize the pattern of hemoglobin changes during the Vuelta.

A higher-than-expected hemoglobin concentration is exactly what is seen in Horner’s data in the second half of the Vuelta. On August 22, Horner’s pre-Vuelta hemoglobin is measure at 15.2 g/dL. Early in the race, this value decreases to 14.4 g/dL, before dropping to a race low of 13.5 g/dL on September 4, a decrease of 11 percent. This would be expected as the stress of the grand tour dilutes the blood, lowering the concentration and expanding blood volume. But then his hemoglobin values rebound to 14.3 g/dL and finish at 14.6 g/dL. The last value is the highest in race value from the entire Vuelta.

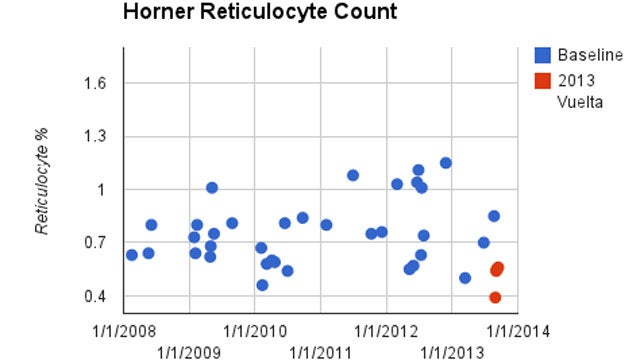

The second element of Horner’s bio passport that causes concern is the reticulocyte count. Reticulocytes are immature red blood cells. They are present in the blood in higher numbers when the bone marrow is rapidly producing new red blood cells and in lower numbers when the bone marrow is suppressed. When an athlete transfuses red blood cells or finishes a course of EPO the bone marrow is suppressed because of the excess hemoglobin. Anytime the reticulocyte count is lower than expected it is an indication that a course of EPO or a blood transfusion may have been used.

Above is Horner’s complete reticulocyte count from his published bio passport data. The Vuelta values are highlighted in red.

Horner’s in-race Vuelta reticulocyte counts include the lowest observed value from his entire profile at 0.39. The four in-race values average out to 0.51+/- 0.08, compared to 0.76 +/- 0.18 for the remainder of bio passport. These averages suggest a suppression of 33% during the Vuelta—a statistically significant difference. (p < 0.05). The statistics tell us that suppression was unlikely to occur from random chance alone.

My observations on Horner’s bio passport prompted Shane Stokes of Velonation to talk with anti-doping authority Robin Parisotto who works with the Athlete Passport Management Unit in Lausanne, France. “It is not 100 percent clear that there is anything untoward happening,” Parisotto told Velonation, “[but] there’s certainly unusual patterns.”

He Horner’s bio passport to other profiles he has seen working as an anti-doping authority “…most of those that come across to us are suspicious. Most are there for a reason. What I have seen with this particular profile is similar to those other profiles.”

Your next question may be, what was Horner thinking? In an interview with Matthew Beaudin for Velonews Horner stated that “when you win a grand tour, there’s a lot of skepticism that surrounds it. So I nipped it in the bud; here’s the results, and it’s all done.” His move it seems was born out of frustration with a sport that couldn’t believe what it had seen out on the roads of Spain. The data release, Horner thought, would be the trump card that silenced his critics. He even called on Beaudin and the rest of the cycling media to ” [pay] the money to have a professional look at my blood results and then post to everybody on the web page about how clean my results are? Because I know my results are clean.”

As it turns out though, Horner may simply not have . “Of course, when I look at it, I don’t have a Ph.D., Matt,” Horner said recently. “So when I look at it, I don’t know what it means, but all I know is that the numbers are the same all the way through from 2008 through the Vuelta win.”

What would have made Horner’s bio passport profile reassuring?

In the context of a Grand Tour, there are two main elements. The first is a decrease in the hemoglobin concentration due to dilution from plasma volume expansion. The second is the absence of significant changes in reticulocyte count from baseline.

In published research studies, Morkeberg et al (2009) reported an average Hgb g/dL decrease of 11.5 percent, ranging from 7-21 percent for Tour de France riders, Corsetti et al (2012) reported a more modest decline in Giro riders of 6 percent, and older Vuelta data from Chicharro et al (2001) showed an average drop of 9 percent. The Corsetti et al (2012) paper reported no statistically significant change in reticulocyte count. My review of the literature failed to find any studies demonstrating decreases in the reticulocyte count due to competing in a grand tour.

Pooling the data together, the decrease expected during a grand tour works out to 9 percent. In Horner’s case this means that once his hemoglobin dropped to 13.5 g/dL it should have stayed low, somewhere around 13.9 g/dL. His reticulocyte count should not have stayed much below his bio passport average of 0.76.

Meanwhile, as of late October, Horner with a team for the 2014 race season.