As the world learned just before the start of this summer's Tour de France, federal investigators are pedaling furiously toward Lance Armstrong's back wheel, hoping to solve the enduring mystery of whether the seven-time Tour winner really did cheat during his legendary cycling career. Floyd Landis, the disgraced winner of the 2006 Tour, got the pursuit going, saying last May that he had used drugs and had blood transfusions during his careerÔÇöand lied about itÔÇöand claiming that Armstrong had cheated, too. According to allegations that first surfaced in The Wall Street Journal, Armstrong and team director Johan Bruyneel introduced Landis to systematic doping within the old U.S. Postal Service squad, with Armstrong supposedly explaining how to transfuse blood packed with performance-boosting red blood cells.

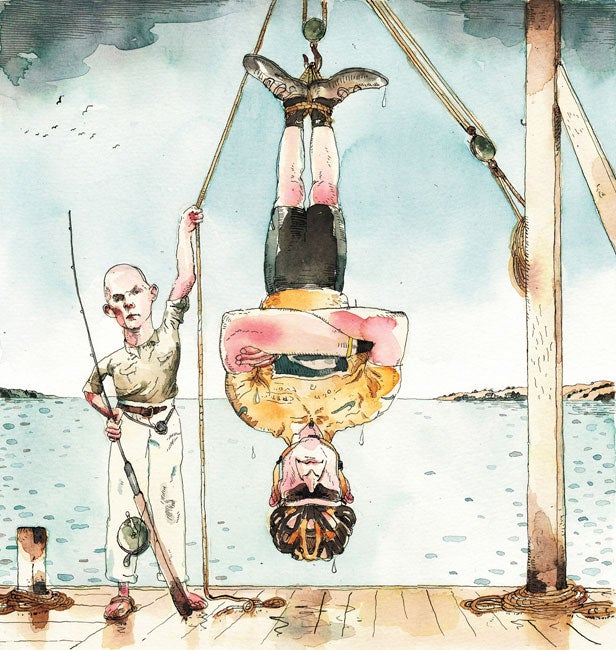

Jeff Novitzky

Jeff Novitzky

Jeff NovitzkyAnd with that charge, an all-important figure entered the story: Jeff Novitzky, a six-foot-six, chrome-domed, gun-packing G-man who's an investigator with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. The 43-year-old Novitzky, the man who famously broke the BALCO drug scandal, had already been looking into doping rumors surrounding a low-level Los AngelesÔÇôbased cycling team called Rock Racing but quickly turned his attention to Armstrong once Landis started talking.

The FDA? Not the FBI or the DEA? It is a bit puzzling at first. Questions have been raised about why the FDA would be investigating Rock Racing to begin withÔÇöthe possible involvement of performance-enhancing drugs presumably provided the rationaleÔÇöand you don't have to love Armstrong to wonder how an FDA agent has managed to harness the fearsome power of the Justice Department to investigate cheating incidents that, if they happened at all, happened mainly in Europe. Federal officials won't explain, because they refuse to acknowledge that there even is an investigation, although it's been a big story in the WSJ, The New York Times, and many other news outlets. It's also widely known that a grand jury, assembled in Los Angeles, has been taking testimony that could lead to various federal charges against Armstrong.

According to reports, Novitzky, with the backing of the U.S. Attorney's Office in Los AngelesÔÇöand the de facto partnership of the United States Anti-Doping Agency (USADA), a private bodyÔÇöhas contacted, and sometimes subpoenaed, current and former Armstrong teammates like Landis, George Hincapie, and Tyler Hamilton, along with employees at sponsors like Trek and Nike. Greg LeMond, a frequent Armstrong scourge, has been asked for documents relating to a past civil case in which LeMond battled Trek over the manufacturer's sales of his signature bikes, with Trek saying LeMond devalued the brand by accusing Armstrong of doping. It's also clear, based on conversations with many sources in a position to knowÔÇömost of whom requested anonymity, fearing legal repercussionsÔÇöthat Novitzky has targeted peripheral figures, including people who may have testified in old civil cases involving Armstrong that touched on doping.

Reportedly, Novitzky wants to know whether Armstrong perjured himself when he swore in those cases that he'd never doped and whether he somehow defrauded the Postal Service by using its sponsorship dollars to obtain doping products and win titles under the false pretense that he was racing clean. If that seems like a convoluted path of attack, it is, but such accusations can be a powerful tool. They give Novitzky justification for federal involvement, subpoenas, and the interrogation of witnessesÔÇöwith the possibility that he might level new charges against anybody he catches in a lie.

Armstrong, of course, has long been a spoke in the craw of the anti-doping agencies, so it's no surprise he's still considered big game, even in the twilight of his career. The World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA)ÔÇöin the person of its former chief, Dick PoundÔÇöhas accused him of doping before, triggering complaints from Armstrong's lawyers that led to an International Olympic Committee rebuke of Pound. Still, both USADA and WADA think he's gotten away with wrongdoing and has become rich and famous as a result. Now they want Armstrong, at long last, to admit he cheatedÔÇösomething he says he'll never do because it didn't happen. (Armstrong, through his lawyers, declined to comment on the situation for this article.)

In this take-no-prisoners struggle, Novitzky is the avenging angel for the anti-doping agencies and Armstrong's enemies. Don Catlin, former director of the UCLA Olympic Analytical Laboratory, one of the best dope-testing labs in the worldÔÇöand a man who admires Novitzky but has become concerned about the government's growing role in policing sports dopingÔÇöbelieves the current investigation was instigated by USADA. “Lots of people do not like Lance Armstrong,” he says, “and they are convinced he did [dope] and they want to expose it.”

Tim Herman, Armstrong's Austin-based lawyer, says that USADA head Travis Tygart and USADA-affiliated lawyer Richard Young have been sitting in on some of Novitzky's interviewsÔÇöa story supported by another source. Tygart declined to discuss this issue, but if true it would represent highly unusual participation by a private outfit in a federal investigation.

“USADA has got to be happy to draft off the work of Jeff Novitzky,” says Kevin Ryan, the former U.S. attorney for the Northern District of California. Ryan, whose office prosecuted the BALCO doping cases put together by Novitzky starting in 2002, says that Novitzky “has been doing lots of the heavy lifting” for USADA. “They should be thanking their lucky stars for Jeff.”

Those on the receiving end of Novitzky's work have another view, sometimes using words like “thug.” But they're usually people Novitzky has targeted, or their lawyers, so hardly anybody pays attention. One thing everyone agrees on is that Novitzky won't stop. “He is very dogged, very determined, very focused,” Ryan says. “If I were a professional or other athlete, I would not relish the fact that this guy might be on my tail.”

NOVITZKY, WHO ALSO declined to be interviewed for this article, is the son of Don Novitzky, a high school basketball coach of local renown around the peninsula south of San Francisco. His hoops genes and height made him a hardcourt star at Mills High School, in Millbrae, but his most impressive talent was in the high jump. In his senior year, he was a contender for a state championship, but he had a bad day during the state meet and failed to make the finals.

Plagued by injuries as a basketball player, Novitzky knocked around colleges before landing on his home turf at San Jose State, mostly riding the bench on a team that was frequently clobbered. Even so, his coach, Stan Morrison, valued his presence. “He was one of the brightest I ever coached, both in basketball and in life,” Morrison says. Novitzky had a gift for reading people. He was always aware of who on the opposing team was in foul trouble and thus ripe for on-court pressure.

After graduating in 1992 with an accounting degree, Novitzky went to work as an agent for the Internal Revenue Service, staying in the Bay Area, where he married and started a family. For nearly a decade, he did what IRS agents do, quietly investigating tax fraud and other financial crimes.

Meanwhile, in practically the same neighborhood, a man named Victor Conte Jr. was operating a sports-supplement business called SNAC and a blood-testing service for athletes called BALCO, short for Bay Area Laboratory Co-Operative. Exactly what prompted Novitzky to start poking around BALCO remains murky. In 1995, a Conte client, Gregg TafralisÔÇöa world-class shot-putter who worked out at the College of San MateoÔÇöwas suspended for doping. Local track-and-field insiders like Tafralis's coach, Mike Lewis, and Lewis's brother, Pat, both friends of the Novitzkys, were aware of rumors surrounding Conte and BALCO. According to one source, there may have been bad blood between the Lewis brothers and Conte, but Mike says he never suggested to Novitzky that BALCO be investigated. One way or another, BALCO caught Novitzky's attention, and he started dumpster-diving on his own time to look for evidence.

Catlin, who taught Novitzky about the world of sports doping after the agent personally found syringes and empty drug-product boxes in BALCO's trash, says he queried Novitzky about his motivations in the case, but the agent never opened up about it. Ultimately, Catlin was left with the impression that “it was just there, facing him, and he was an athlete and obviously something needed to be done, and he had access and away he went.”

During BALCO, Novitzky targeted some of the biggest names in American sports, including baseball slugger Barry Bonds and Olympic sprinter Marion Jones. Such headhunting is important, because federal agents from many agencies have to compete for the attention of U.S. attorneys, who file cases based on office priorities. Sports doping, with a few questionable monetary transactions thrown inÔÇöConte eventually pleaded guilty to money laundering and steroid distribution and was sentenced to eight months of prison and home confinementÔÇöwould not normally rise to the top. But Novitzky had an easy time convincing Ryan's office to go after BALCO, because the case had what Ryan calls “natural sex appeal.”

In BALCO and related cases, Novitzky and the government did just what Novitzky used to do back at San Jose State: He targeted people in foul trouble and used intimidation to take them down.

Opinion on whether his tactics were improper varies, depending on whose team you were on, but some criticized him as an anti-doping zealot making a name for himself, less interested in building serious cases than in publicly shaming famous athletes. To this day, Conte insists Novitzky is himself a perjurer. “He lies and cheats,” Conte says, citing misstatements he claims Novitzky made in court affidavits. “So we have a liar and a cheater going after a group of liars and cheaters. Do the athletes cheat? Yes. The government cheats to win, too.”

Paula Canny, the San Francisco attorney who has represented Greg Anderson, Barry Bonds's trainer, says “Novitzky is to law enforcement the very thing he accuses Lance Armstrong of being in bicycling. He pushes the envelope as far as it can be pushed”ÔÇöarguably too far, she says, into “illegal.”

Outwardly, Novitzky did what most federal agents do, with the attitude that feds are trained to have: be polite, and don't act like a bullying TV cop. One former pro bike racer who was recently interviewed by Novitzky says the agent treated him “fairly and decently.” Another interviewee seconded this, saying, “I said to him, 'You are not the jerk I thought you were.'” USADA's Tygart describes Novitzky as “thorough, tenacious, but overly fair and compassionate.”

“Overly fair and compassionate” might be a bit much, but some defense lawyers say Novitzky is a man of his word. One said, “I do not have any problems with him from a personal standpoint. He has certainly, never in my cases, done anything I deemed inappropriate or unfair. And I've dealt with other agents who are real assholes.”

THIS DOESN'T necessarily mean Novitzky operates without an agenda, one that might be more about spanking prominent athletes than convicting people of crimes. When asked whether, in light of the meager legal payoff, he has any regrets about BALCO, Kevin Ryan laughs ruefully and says, “It did turn my world upside down, yes.” But he insists that taking the case was the right call. BALCO brought lots of attention to the issue of drugs in sports. It launched congressional hearings. It sent a social message.

Those arguments appear to have worked on the U.S. attorneys in Los Angeles. Based on conversations with several sources, it seems clear that Novitzky, USADA, and government investigators are using the same strategy Novitzky followed during BALCO. He's obtaining evidence of past wrongdoing, even if it involved acts that are not crimes, like sports doping, and then using that evidence as leverage to force people to talk. He's also zeroed in on those who backed up Armstrong's denials of doping in past civil cases and accused them of lying.

As he did during BALCO, he's using the threat of perjury charges in a process that works like this: You ask somebody, “Did you use performance-enhancing drugs?” If they're later found to have lied, you can say they've violated Title 18, Section 1001 of the U.S. CodeÔÇöwhich is what sent Martha Stewart to jail. Proving that case is tough; defendants can claim entrapment or simple misunderstanding of questions, but it can work if documents, witnesses, or doping test results contradict the interviewee. If the lie happens under oath before a jury, the person has committed perjury.

This admit-or-face-prosecution strategy has ensnared former major league pitcher Roger Clemens, who was indicted in August for perjury for lying under oath to Congress. This happened because Novitzky and federal prosecutors made a deal with Clemens's former trainer Brian McNamee. In exchange for immunity, McNamee was forced to testify against Clemens to baseball's Mitchell Commission in 2007. Like USADA, the commission was a private body with no subpoena power of its own. Even so, lying to Mitchell, the government said, would be like lying to a government agent. Later, when Clemens told Congress he hadn't used performance enhancers, this set up a “he said, he said” contradiction that the government will now pursue in court.

Though some prosecutors and defense attorneys think this is a low-rent strategy, perjury charges are effective, and can prompt many people to confess. In the case of an athlete like Armstrong, a confession would be seismic. He stands to lose endorsements, titles, and public goodwill toward him and his LiveStrong cancer foundation.

As for the defense's side, so far it appears that Armstrong's lawyers are focusing on impugning the integrity of the investigation, claiming that some pro riders may have been given sweetheart deals of immunity by USADA if they rolled over on Armstrong. And they point out, of course, that Armstrong never failed a doping test in his long and storied career.

Whatever happens next, this process is likely to take a long time. BALCO was first searched by Novitzky in 2003. After seven years of legal maneuvers, Barry Bonds's trial date for perjury and obstruction has finally been set, for March 2011. Armstrong's lawyers have yet to receive any kind of target letter, a formal notice that their client is the subject of a criminal investigation. In fact, the U.S. Attorney's Office has not communicated with them at all, so any possible charges are still speculation probably based on strategic leaks.

Meanwhile, Novitzky, who moved to the FDA in 2008 and works for its Office of Criminal Investigations (OCI), has been given wide latitude to work as a free agent with no fixed schedule. According to a source familiar with OCI's workings, “they feel like they report to no one and can do what they want. All the agents want to do is spend all their time on high-profile cases that, at best, tangentially involve the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act,” meant to protect the health and safety of the nation. So nobody is going to call Novitzky off.

As this investigation unfolds, it's important to keep in mind that, on one level, it's not really about crime or indictments. It's about publicly shaming an athlete who Novitzky suspects has broken his covenant with the public. Novitzky is quite capable of committing an unlawful act to complete that mission, just as Conte and Canny suggest.

During the BALCO investigation, Novitzky once asked a judge to approve a search warrant of computer files at a company called Comprehensive Drug Testing. The files were secret, the results of a trial run of dope tests conducted by Major League Baseball. The judge granted the warrant but with clear restrictions. Novitzky could not view any files until a computer-forensics expert had isolated the records of the few players Novitzky claimed were linked to BALCO, and then he was to view only those files.

Novitzky defied that order. He rooted out the files on all the players tested and took the list, an act the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit later called “unlawful.” Other judges called it a “callous disregard for the rights of third parties” and “harassment.”

The names of players found their way into selected newspapers. It was a victory for the mission. The message was sent.