TYLER HAMILTON, WHO IS by some accounts both the toughest and nicest cyclist on the planet, has a certain look he gives whenever he tells one of his stories. It is subtle, but since Hamilton, 33, has built a career on subtle moves, it is worth attending.

Tyler Hamilton in Spain

“I prefer to let my legs do the talking”: Tyler Hamilton in Girona, Spain, April 2004

“I prefer to let my legs do the talking”: Tyler Hamilton in Girona, Spain, April 2004Tyler Hamilton in Girona

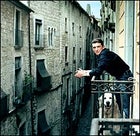

Room with a view: Hamilton with his dog, Tugboat, on the balcony of his Girona apartment, one floor up from former teammate Lance Armstrong

Room with a view: Hamilton with his dog, Tugboat, on the balcony of his Girona apartment, one floor up from former teammate Lance ArmstrongTyler Hamilton

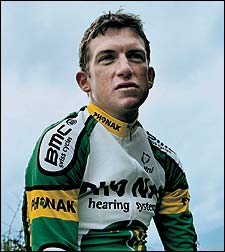

Front runner: “If I fall on my face,” says Hamilton, “there’s no one to blame but me.”

Front runner: “If I fall on my face,” says Hamilton, “there’s no one to blame but me.”

Here’s how it goes: First Hamilton makes eye contact; then he widens his boyish green eyes a fraction of an inch in faint surprise; then he tilts his head in an understanding nod.

“I crashed and broke my shoulder early”—eyes lock on—”but the doctors didn’t really know it was broken”—eyebrows up—”so I just kept riding”—nod, smile. Pretty soon you’re nodding and smiling, too, and the air fills with warm, brotherly affection, along with the unmistakable implication that if you’d somehow been in the same situation (which happened to be at the 2002 Giro d’Italia, a three-week race in which Hamilton finished second), you would have done exactly the same thing.

The irony of this gesture—that a man best known for enduring pain might put his energies into the pleasure of others—is not something Hamilton would appreciate, or even notice. It is simply what he does. It has fueled his ascent from washed-up college skier to a position as Lance Armstrong’s lieutenant from 1999 to 2001, then to a spot as lead rider on the talented Danish CSC team in 2002, and to a fourth-place finish for that team in the 2003 Tour—despite racing three weeks with a fractured collarbone. At the 2004 Tour, Hamilton will captain a newly fortified Swiss team, Phonak, and take on the singular aim—insert your own Greek myth here—of supplanting his friend and former leader at the pinnacle of the cycling world.

Of course, that’s not the kind of thing Hamilton would actually say—the most he’ll tell you is that he hopes to finish in the top three. It’s hard to believe he will find environs more hopeful than the ones he’s in now, seated comfortably amid the springtime bustle of an outdoor café in Girona, Spain, where he trains during the European racing season each January to fall. But according to his rules, Hamilton isn’t talking about self-centered things like hope or ambition—no, he’s doing something more basic. He’s counting his refurbished teeth.

“Eleven, or twelve, I think,” says the Marblehead, Massachusetts, native, referring to the number of molars he had recapped after grinding them down to their nerves during the Giro. “It was a lot of trips to the dentist, that’s for sure. And that drive into Boston—that’s where my dentist is—that’s no fun. Traffic can get pretty bad, you know?”

We know. We also know that Tyler Hamilton’s niceness, like Britney Spears’s appeal, is a phenomenon that is often observed but rarely comprehended. His five-foot-eight, 135-pound form radiates an almost paternal alertness to small needs, his hands reaching out to open doors, tickle babies, pay for coffees, scratch exactly the right spot behind a dog’s ears. It would be easy to miss what dwells quietly beneath, namely a massive deposit of granitic reserve, a quality perfected by English Protestants and exported to Hamilton’s New England hometown, a quality built on one rule: The bolder you are, the more deferential you must be.

“I prefer to let my legs do the talking,” Hamilton likes to say. The rest of his body is not exactly uncommunicative: There’s the long, white scar along the middle finger of his left hand, the result of a bloody crash in last year’s Tour of Holland, in which he also cracked his femur. There’s the tentacle of a scar above his right eyebrow, courtesy of a car door he encountered while warming up for a 2002 race, and the usual hieroglyph of road-rash scars on his legs and elbows—all of which Hamilton regards with cheerful indifference, or at least seems to.

“Somewhere deep inside, he’s got that edge, that urge to kill,” says former U.S. Postal Service teammate Jonathan Vaughters, 31. “The sport’s too hard not to have it. But he buries it very well. I’m not saying he does it intentionally as a tactic. But as a tactic, it works.”

Exactly what Hamilton is burying is the more interesting question, and might be why some oddsmakers slot him a notch above the second tier of Tour contenders, though still behind Armstrong and German Jan Ullrich (the 1997 Tour winner and five-time runner-up). There is evidence for their optimism: This is Hamilton’s first year as sole team leader, and he will enjoy the unquestioning support of Phonak’s eight other Tour riders, many of whom he handpicked. But there are other, less tangible reasons. As last year’s Tour vividly illustrated, Hamilton, a strong climber and time-trialist, possesses something the others don’t: a whiff of mystery, the sense of something unknowable shifting beneath the placid surface.

“Once, when I was 14 and he was 11, we were fighting,” his brother, Geoff Hamilton, 36, says. “I nailed him, right on the button, and he went down hard. I was a lot bigger than him, and so I figured it’s over. And then… . Ty bounces off the floor and comes at me, boom, like a tiger. I remember thinking, Whoa, what is this?”

LIKE MOST TYLER HAMILTON stories, the tale of his 2003 Tour de France follows a three-act dramatic formula: first a fateful crash, then a devastating injury, followed by an improbable comeback.

Act I: A sunny July afternoon in the riverside village of Meaux, finish of Stage 1. In his second season after leaving Armstrong’s USPS team, Hamilton has elevated his game to a new level, becoming the first American to win the brutal 160-mile Liège–Bastogne–Liège race, in April, then winning the Tour of Romandie a week later. With the skilled CSC team behind him, he carries high hopes for the Tour, all of which quite literally crumple on a narrow curve near the first day’s finish, when the usual thing happens—one rider twitches, another puts a foot down—sparking a hideous pile-up that knocks Hamilton over at 40 miles per hour.

“That hurt a lot,” Hamilton says.

Act II: Two doctors x-ray and examine him. The right collarbone is fractured, a clean crack in the shape of a V. The Tour’s official newspaper is notified, headlines are written: Hamilton Out. Then a third doctor examines him and notes that, while the bone is broken, it is not displaced. In a Hamiltonian stroke of luck, the fracture occurred near the spot where he broke his collarbone in 2002, and a mass of fresh bone growth has prevented the new fracture from spreading. “C’est possible,” the doctor says.

Act III: Hamilton, pale and bandaged, wobbles out for Stage 2. His suitcase is packed and brought to the first feed zone in anticipation of his dropping out. His 34-year-old wife, Haven, who met Hamilton at the 1996 Tour du Pont, where she was volunteering, ponders how she’ll console him. But he finishes the 127-mile stage in the lead group, and the Tour is never the same.

“On a pain scale of one to ten,” Hamilton says, “that was ten.”

“It is the finest example of courage that I’ve come across,” decrees veteran Tour doctor Gerard Porte in the press, adding that your average person would have taken four weeks off work. Historians root eagerly through the Tour’s ample cupboard of noble wounded—Pascal Simon’s broken shoulder blade in 1983; Honoré Barthélémy’s broken shoulder and wrist, and injured eye, in 1920; Eddy Merckx’s 1975 finish with a broken jaw—and watch as Hamilton steadily matches them all. The squad of filmmakers who are featuring Hamilton as the centerpiece of a 2005 Imax movie on how the brain works (called Brain Power) keep their cameras rolling, scarcely believing that God could script so perfectly. Inevitably, a rival team director accuses Hamilton and CSC of fakery, precipitating the rarely seen spectacle of a team parading X rays to prove one of their riders really is injured.

Barred by anti-doping regulations from taking any useful painkillers, Hamilton turns to scads of Tylenol and other, less conventional methods—like a good-luck vial of salt in his jersey pocket. Each night, CSC’s lanky Danish healer, Ole Kare Foli, applies acupressure and “channels energy” while Hamilton sleeps.

It seems to work. A few days later, on the steeps of L’Alpe d’Huez, in Stage 8, Hamilton not only rides in the lead group but attacks four times. Then things suddenly get worse. Favoring the injury, Hamilton compresses a nerve in his lower back. The night after Stage 10, Foli tries to massage Hamilton to loosen him up for the needed spinal adjustment, but the pain is too great.

“That really, really hurt a lot,” Hamilton says. “At least what I remember of it.”

Haven has more vivid recollections. “Ty was lying there in the dark, and he couldn’t move,” she says. “Then he says, ‘Just do it, do the adjustment now.’ Ole went to straighten him out, and Tyler’s screaming and Ole is crying and I’m crying, wondering what could be worth all this.”

Eight days later, Hamilton provides a succinct answer with an incredible Act IV in Stage 16, a day in which he is nearly dropped early on, is ridden back to the pack by his team, then breaks away and rides alone through the mists up Bagarguy, one of the Tour’s steepest climbs, his eyes grimaced to slits, his cheeks, according to one account, streaked with tears.

He outrides the superior power of the chasing pack for 70 miles and wins his first Tour stage, giving television commentators plenty of time to let their voices dissolve with emotion as they declare it one of the longest and most courageous solo breakaways in Tour history. Hamilton’s unexpected victory briefly eclipses all other story lines, including that of his former teammate Armstrong. As Hamilton sums things up, “That day felt really good.”

It is a measure of the Tour’s insularity that the full impact of Hamilton’s feat doesn’t hit home until a couple weeks later. It happens in an unlikely place, the trading floor of the American Stock Exchange, where he’s been asked to ring the opening bell. Hamilton is a touch nervous about going there—a skinny cyclist in the trading pits of Wall Street? He finished fourth, remember?

Hamilton is game, though, and he follows the script, ringing the bell and making the rounds amid the craze of shouting NFL-size guys in their luridly colored jackets. Then it happens. Out of the corner of his eye, he notices one of the big shaved-head guys pointing at him and whispering to another big shaved-head guy. And pretty soon that second guy is whispering to a third guy, and before long a whole burly tribe of traders gather around Ty and they’re going bananas! They know who he is, the whole collarbone story, and, what’s more, they love him! Because in Hamilton the pit jocks recognize one of their own, a regular Joe with a secret streak of balls-out insanity, and they can’t help but mark the occasion by giving him a new name: Tyler Fucking Hamilton. And all of a sudden Tyler Fucking Hamilton is shooting the breeze about the Yanks and the Sox, inhabiting this strange high ground of celebrity. Almost as if he’s been preparing for moments like this his whole life.

CRAZYKIDS, THEY CALLED IT. Not the parents—they didn’t call it anything, because most didn’t know it existed, and those who did know wished they didn’t. This was strictly kids-only, six or eight of them, united around a simple proposition: to go out in the woods every day and do something big. Climb a mountain. Cross a frozen river—or, better, a partly frozen one. Tyler was 13, and it was how he spent his winter weekends with a few other kids at New Hampshire’s Wildcat Mountain ski school, in the White Mountains. The group included Mark Synnott, who would grow up to be a big-wall climber, and Rob Frost, now a noted adventure filmmaker. But back then they were a bunch of restless pups who wanted to see how close they could sneak toward the edge and not get hurt.

If they did get hurt, they were usually too numb to notice. Wildcat Mountain, near Mount Washington, is a squat, north-facing slab of ice to which the term “resort” is usually applied ironically. Godawful weather is the norm, and from a tender age Hamilton was faithfully submitted to its charms, his family making the three-hour trip from their Marblehead home each winter weekend. Though Tyler had already displayed a somewhat alarming tendency to find pain (broken ankle, several stitched-up chins), Wildcat was the place where he spent time in its company.

After all, his parents, Bill and Lorna Hamilton, had met skiing Tuckerman’s Ravine, a famously gnarly hike-in descent in the White Mountains, and had essentially stayed outdoors ever since. If you were a Hamilton in the 1980s, it was a given: Summers were spent sailing, winters skiing, and in between were rafting trips to Alaska and climbs on Mount Washington. Craziness was permitted on these adventures, even tacitly encouraged. Within the walls of the Hamilton house, however, another set of rules prevailed, mostly enforced by Bill, a computer consultant. Telephones were answered properly, meals attended punctually. And one of the most explicit rules regarded boasting.

“It just was not done,” Jennifer Linehan, Tyler’s 37-year-old sister, remembers. “If you talked big about something you’d accomplished, they would listen politely and then move on.”

Not that there weren’t things to boast about. All three Hamilton kids were good athletes, and by his early teens Tyler was one of the top downhill racers in New England. But that didn’t mean he could act like it. After winning races, Hamilton was required by his father to congratulate the dejected losers. Hamilton would make the rounds, nodding and smiling—I just got lucky this time; next time it’ll be you—and pretty soon the other kids would be nodding and smiling right along with him.

In 1987, Hamilton went to Holderness School, a sports-minded boarding academy near Plymouth, New Hampshire, where Crazykid energy was funneled into a grid of old-fashioned Episcopalian discipline, and where Hamilton roomed with the son of former East German cyclist Peter Kaiter, who introduced Hamilton to European-style bike racing. Hamilton attended mandatory church services and was instructed by people like Phil Peck, a former Olympic nordic coach who could recite the Book of Common Prayer and anaerobic-threshold statistics with equal authority.

In 1990, Hamilton entered the University of Colorado, in Boulder, as a freshman and joined the school’s ski team as a walk-on. The following year, he broke two vertebrae in a mountain-bike crash, ending his downhill career and sending him to pedal off his frustrations in the Rocky Mountains. A promising part-time cyclist, Hamilton quickly excelled when it became his focus; he joined the university’s cycling team in 1992—winning the collegiate nationals in 1993—rode for the U.S. national team in ’94, turned pro in ’95, helped Armstrong win the Tour with USPS from 1999 to 2001, and went to the CSC team in 2002. Each year he moved to a new level. “Baby steps,” Hamilton calls them.

“Tyler started later than most,” says Jim Ochowicz, who coached Hamilton at the 2000 Sydney Olympics and serves as president of USA Cycling, the sport’s governing body in the U.S. “He might be 33, but his body isn’t as beat up as a lot of the other guys who started cycling at 15. He’s still got room to explore.”

THAT EXPLORATION reached new territory this winter when Ochowicz helped arrange an agreement for Hamilton to join Phonak, a Swiss team, sponsored by a hearing-aid company, with a $9 million budget and equally large ambitions. Their offer—to build a team solely around Hamilton for the Tour de France, to give him say on personnel and equipment and a high-six-figure salary—was too good to refuse. Being team leader brings with it new pressures, which Hamilton welcomes with a metaphor that one hopes will prove less than apt. “If I fall on my face,” he says, “there’s no one to blame but me.”

Having friends will help—particularly when one of them happens to be the peloton’s unquestioned boss. Unlike some of Armstrong’s departed teammates, Hamilton has gone out of his way to maintain a good relationship with the Texan. When Postal’s team director, Johan Bruyneel, urged then-domestique Hamilton to go after his first major victory at the 2000 Dauphine Libere, Hamilton would not ride ahead until he got the OK from Armstrong himself. A year later, before departing Postal for CSC, Hamilton involved his team leader to the extent that by the end it seemed almost like Armstrong’s idea. And when a certain Girona apartment became available in 2001, Hamilton called Armstrong, who’d already bought the first floor, to see if he’d be OK with the Hamiltons living above. “He didn’t want it to be weird,” Haven says. “And of course Lance was happy about it.”

Travel schedules being what they are, the two top Americans cross paths mostly at races but remain, in Geoff Hamilton’s estimation, “professional friends,” exchanging occasional e-mails. When they arrived in Girona this winter, Armstrong and girlfriend Sheryl Crow hosted the Hamiltons at a small dinner party. It’s the sort of relationship that suits both riders, and has suited the sport’s headline writers no less well: Lance and Tyler, the bold Texan and the reserved New Englander, two American archetypes.

“Lance and I have two different characters,” Hamilton says. “Lance is good at talking, and he’s got what it takes to back it up every step of the way. I’m quieter. What he does works for him, and what I do works for me.”

A blessedly sunny Friday in March. Team Hamilton heads to the office—namely a short, innocuous stretch of gently rolling two-lane a few miles north of Girona known as the Strip. Today is a motor-pacing day, which means that Haven drives their Audi Quattro a few inches in front of Hamilton’s front wheel, shielding him from the wind. She motor-paces him for one stretch, then he does a lap alone, then they repeat, riding back and forth along the Strip for two or three hours.

“Boring, isn’t it?” says Haven, who is Hamilton’s confidante, chef, and partner in the Tyler Hamilton Foundation and the company Inside Track Tours, which, among other things, gives clients a view of the Tour each summer. But like any good New Englander will tell you, boring can have a higher purpose: in this case, the subtle but profound changes her husband’s body is undergoing in preparation for the Tour. Already slender, he will lose five more pounds, a task made difficult by his sturdy skier’s physique. His body fat will drop to practically nothing, and his skin will become, Haven says, like cellophane. “If I touch him in the middle of the night,” she says, “his body will be red-hot, like his metabolism is revving.”

There are other changes, too. When races approach, particularly before time trials, Hamilton slips into what Haven calls “race mode.” Life will get quieter—no visitors, no media, no distractions. His family knows the rules: no phone calls the day or two before a major race, longer before the Tour—or, if you do call, plan on it being rather brief. His brother, Geoff, calls it the “no go” area.

“I’m not sure what he does,” Geoff says. “I just know that this is how his mind works, getting ready to take the pain, to do what it takes.”

As it happens, the area of the human brain that handles pain signals is the same area that helps create and interpret emotion. It’s a roughly walnut-size spot called the anterior cingulate cortex, and its influence on our personality is gigantic—”the seat of the soul,” some biologists have called it. “I think the brain of a guy like Hamilton is wired differently,” says Dan Galper, a senior research associate in the psychiatry department at the University of Texas. “To endure what he endures and stay in control, there’s no question that something unique is going on.”

The notion that pain—as opposed to, say, sight or smell or musical ability—is intertwined with our essential personalities is one that would seem to apply to Hamilton. Perhaps he’s nice because he’s tough, and he’s tough because he’s nice. At least to a point.

Yes, now it can be told: There are times when Tyler Hamilton is not nice. During a race a couple of years ago, Hamilton handed his sunglasses to a mechanic in his team car to be cleaned. Seconds ticked away, riders sped past, and the mechanic was still fervently wiping and rewiping the glasses. Finally, Hamilton had had enough. “How long does it take,” he yelled, “to clean a pair of fucking glasses?!“

Back in the Girona café after training, however, afloat on a pleasant river of conversation, such an outburst seems very far away. Except for one moment, when Hamilton is asked what he thinks about while in race mode.

“Ummm,” he says, his eyes focusing on something in the middle distance. “That’s a good question.”

He answers eventually—talking about memorizing the course and mulling tactics—but there are no widened eyes, no nod, no friendly intimation of shared ground. You can’t help but get the feeling that here begins the no-go area. Perhaps there are some sorts of wilderness that are best explored alone.