LAST SEPTEMBER, ON THE FINAL DAY of the three-week, 1,851-mile Vuelta a España, 28-year-old Montana native Levi Leipheimer lived out the secret fantasy of every lowly support rider. Leipheimer, a U.S. Postal Service team member at the time, was riding for reigning Vuelta champion Roberto Heras of Spain, but after 20 days of inspired pedaling he sat in fifth place—just two spots behind Heras—with only a 24-mile time trial remaining.

Traffic jam: TDF racers between Calais and Antwerp, July 2001

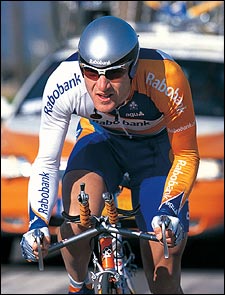

Traffic jam: TDF racers between Calais and Antwerp, July 2001 Quick study: Leipheimer in Spain

Quick study: Leipheimer in Spain

“It was a bit awkward,” Leipheimer recalls. “Roberto was the defending champion, but I wasn’t going to hold back.” He certainly didn’t. His second-place time trial put Heras in fifth and sealed a third-place finish overall, the best ever by an American in the world’s third most prestigious stage race. “Levi has always been a very good time trialist,” says USPS operations director Dan Osipow, “but defeating the defending Vuelta champion was not something we were expecting.” Three months later, Leipheimer inked a lucrative two-year deal with Dutch powerhouse Rabobank, which means that on July 6 he’ll be leading one of cycling’s top squads.

Of course, American success on hallowed European pavement doesn’t turn heads the way it used to. This season, longtime Lance Armstrong lieutenant Tyler Hamilton rides for Dutch team CSC Tiscali; Kevin Livingston and Bobby Julich are the main support riders for German team Deutsche Telecom; and George Hincapie and Fred Rodriguez have both been ranked in the World Cup top ten. Levi just adds to the American firepower.

So does Leipheimer stand a chance in his first Tour? Perhaps. He took fourth in October’s world time-trial championship in Lisbon, Portugal, and his Vuelta performance displayed the relentless consistency of past cycling greats. But his real challenge, says Julich, will be transforming from garçon to The Man. “It’s different when the pressure of leading a team is on your shoulders.” Especially if you have a team full of young guns ready to pull a Leipheimer

—CHRIS KEYES

RADIO FLYERS

LIKE ANY GOOD MILITARY OP, THE TOUR DEPENDS ON COMMUNICATIONS

Think driving with a Big Mac and a cell phone is dangerous? Try taking the wheel of a Tour de France team car. During Le Tour, Johan Bruyneel, the USPS squad’s field manager, shares a silver Volkswagen Passat with nearly as much communications gear as a 747. While piloting the four-wheel command center around tight corners and over mountain passes, the 37-year-old Belgian listens to play-by-play race reports on the radio, eyes live coverage on a six-inch television screen, chats in four languages on his cell, and sends instructions to the riders—each of whom carries a credit-card-size two-way radio and has a tiny microphone clipped to his jersey. Though Bruyneel putters along just behind the peloton, he’s able to keep tabs on more than 180 competitors and deploy his guys accordingly.

“Everybody depends on communication now,” he says. “It’s changed the races.” Case in point: During the 130-mile L’Alpe d’Huez stage of last year’s Tour, Bruyneel radioed Lance Armstrong and instructed him to play possum for the cameras. “I knew the other teams were watching and listening to interviews,” he says. “I told French TV I was worried because Lance didn’t look good at all.” Sure enough, as Armstrong appeared to fade, rival team Telekom radioed their riders, sending three to the front to increase the pace. Only when Armstrong turned on the gas for the final climb—to win the stage with a two-minute lead—did they realize that Bruyneel had beaten them at their own high-tech game. —DAN STRUMPF

Lance Armstrong stood alone atop the podium after his last three Tour wins, but his victories were built on the backs of a team of world-class riders expected to chase down breakaways instead of chasing the maillot jaune. While some teams, like Spain’s Kelme, stack the deck with pure climbers, and others, like Belgium’s Domo, bank on their sprinters, the U.S. Postal Service team plays a delicate balancing game to give Armstrong a full range of defenses. But putting together a winning team isn’t cheap—Armstrong has a history of handing over his Tour winnings to his teammates ($337,00) and reportedly dishes out another $250,000 from his own pocket. Here’s a guide to the riders pushing for an Armstrong four-peat.

1. THE GENERAL

Wispy Roberto Heras (1), from Bejar, Spain, is a mountain climber par excellence. He’ll be the last teammate to stay with Armstrong in the Alps and Pyrenees, going on the offensive to make the opposition waste energy catching up. Should Armstrong get sick or injured, 28-year-old Heras takes over as team leader.

2. THE MAN

As team leader, Lance Armstrong (2) has the job of doing as little work as possible in the flat stages, while staying on guard for splits in the pack that could cost him time if he gets stuck in the slow half. The 30-year-old Texan has to save himself for when it counts: the grueling climbs and time trials, where he can clinch a win.

3. – 4. – 5. THE CAPTAINS

The role of Spainiard José Luis Rubiera (3) is simple—blow apart the lead pack on uphill climbs. Expect him to take the offensive on stage 14’s Mont Ventoux. George Hincapie (5), the strapping, 6-foot-3, 170-pounder out of Greenville, South Carolina, is master of the flats, reeling in all who escape the peloton.

6. – 7. THE SENTRY

Twenty-six-year-old Christian Vande Velde (6), from Boulder, Colorado, is Postal’s jack-of-all-trades. It’s his job to flank Armstrong through the smaller mountains and valleys, setting a steady tempo to thwart attackers and chase breakaways between mountain passes, when strongmen like Hincapie have been left behind.

Illustration by Ward Sutton 8. – 9. THE FOOT SOLDIERS

Those chosen for the remaining four slots (4, 7, 8, and 9) are the sacrificial lambs—they’ll fetch water bottles and help pace Lance back into the peloton if he gets a flat. Our picks: Benoî Joachim of Luxembourg, Steffen Kjaergaard of Norway, Victor Hugo Peña of Colombia, and Floyd Landis of San Diego.