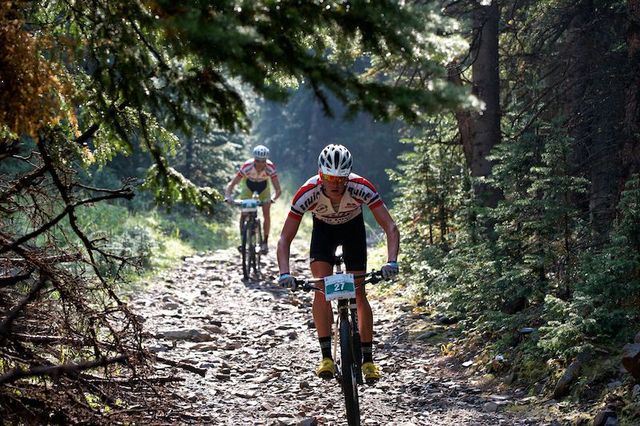

This week, several hundred mountain bike racers are depriving themselves of oxygen and beating themselves silly in the fourth annual . In the spirit of the BC Bike Race and the TransRockies Challenge, this rapidly growing event attracts pro and amateurs alike to race approximately 40 miles each day for six consecutive days. (For the less robust racers, like me—though I prefer to think of it as “more reasonable”—there's also a three-day version.) Each day's stage starts around 9,600 feet in Breckenridge, Colorado, and notches between two-thirds and 1.5-miles of vertical on a mix of singletrack and fire roads. The leaders take between three and 3.5 hours to finish each stage—mortals spend up to double that.

I finished the three-day race on Tuesday and managed to secure a spot on the men's open podium. (Proceed to #5 before you get too impressed.) The course features tons of grin-inducing riding, the vibe is as friendly as a small-town diner waitress, and in spite of a few logistical snafus I'd do it again. Here are a few lessons and impressions.

1. Neutral support is the shit. Ten minutes before the race start while I was warming up, my recently tuned front brake ceased all stopping duties. Five minutes before race start, I sprinted over to Ryan Gaul and Jamie Bissell at the Neutral Support Van and they said they could install a loaner brake but it would probably delay me. Four minutes before race start, they began installation. Two minutes before race start, I had a brand new, fully optional XTR front brake. I was dazed and still trembling with adrenaline when the race commenced and we rolled. If it hadn't been for these guys, my race might have been done before I began. And I heard of them making similar F1 pit-style repairs throughout the event. If you're ever at a race and see a neutral support van, Shimano or otherwise, go over and say thanks. In fact, take a six pack. These guys are unsung heroes.

2. Unlike most roadies—who are overserious and have an immoderate sense of their abilities and self-importance (myself included sometimes)—mountain bikers are nice. Really nice. Most riders in the Breck Epic happily let others in front of them on singletrack. When racers crashed or had a mechanical, others stopped to see if everything was okay and asked if they needed help. The guy that beat me in the overall, Matt Simmons, rode wheel-for-wheel with me on Stage 3, and though we easily could have spent the day glaring at each other, the attacks were offset by friendly conversation. Even the pros are chill: Josh Tostado took 10 minutes out of his warm-up one day to talk to me about the course and tire selection; Ross Schnell gave me friendly pointers on downhilling; and single speed leader invited me to come ride with him at his place in Taos. Race organizer Mike McCormack constantly emphasizes, “It's just a bike race,” and that easygoing attitude pervades the Epic.

3. Laidback is good when it comes to spirit but less good in terms of logistics. On day one, I was first told the stage was 31 miles, then moments before the race it was upgraded to 39. Every single day, the aid stations were in different locations than reported in advance—once by as much as eight miles. Elevation estimates were often half of what was claimed (Stage 2: 3,600 actual versus 7,700 claimed). The maps and GPX tracks were always slightly off, leaving me constantly wondering where I was on the course. In fairness, the courses were incredibly well marked (except for one key turn, which caused some heartache for a small group of racers), the support teams were cordial and relaxed and helpful, and none of these logistical quibbles changed the race. Still, GPS are inexpensive and easy to use these days. The Breck team needs to invest and nail down the particulars.

4. You know that movie The Weather Man, where everyone hates meteorologist Nicolas Cage and and fast food at him in the streets when they see him? I was pretty much right there on Stage 2. At 7 a.m., the forecast called for a high of 65 with a 40 percent chance of showers after noon. By the start at 8:30, it was 40 degrees and raining, and the rain and cold didn't subside until evening. I mean come on, you're a weatherman and you didn't see a 12-hour storm on the horizon? That's kinda like a bike racer not realizing he should bring his bike to the race. It was a brutal day out there, too: wet and sloppy and hypothermic, and everyone was just praying to not get a flat because with such cold hands even tiny mechanicals would have meant lots of lost time or perhaps even dropping out. I spent the first hour after the stage shaking uncontrollably and the next two cleaning my gear. As always, though, racing amnesia has kicked in and in hindsight it now seems like it was kinda fun.

5. It's a race—not everyone should win. And yet at the Epic, which has some 250 participants, there were 19 categories. If you count three podium spots per category, that means that over 20 percent of the field will “win.” Okay, I get that lots of categories and classes mean more participation, more prizes, and keeps people involved and happy. But it makes for a hollow-feeling accomplishment. (Nevermind the lengthy award ceremonies each night to hand out 19 separate stage wins and overalls.) Would I have if, say, the classes had beeen cut in half? Perhaps, perhaps not. Call me crazy, though, but I think getting in the top three should be hard.

6. In the Tour de France, they talk about riders getting stronger as the race goes on—you know, physically getting better with every consecutive day they ride. I think this is a load of crap. Sure, after some good rest you reap the benefits of that hard riding and come back stronger. But you don't just keep riding day-in, day-out and go faster and harder. Your power decreases. You get tired. That's what happens. I say this because, after three stages I was tired. Very tired. Could I have ridden three more stages if time and work had allowed—sure. Would I have been faster and stronger doing it—negative. Having said that, if you're considering the , think hard about six days. Tired as I am and hard as it was, I wish I was still out there.

7. Yep, it's epic. And I mean that in a good way. The courses are well-designed with short, tricky, bony sections offset by miles and miles of fast, buff, beautiful singletrack. There's tons of climbing but only a very small portion of it is so tough you have to walk. The altitude is killer, but from 12,000 feet down over the valleys makes it well worth the effort. No matter how much I felt like coughing up a lung, I still found myself nodding my approval at the riding. And most of all, the people—including the racers, the organizers, and the locals—are fun and charged-up and out for a good time. It's a “big” bike race without all the BS—just tons of good riding. In the end, isn't that why we all ride our bikes?

I haven't raced the TransRockies or the BC Bike Race, so I'm in no position to say if the Breck is better. What I can say is that the format, which sees racers looping back to the same endpoint, makes for fewer logistics and more relaxing than a point-to-point would. Each day, you roll from the finish line back to your condo, where you can sip recovery shakes (a.k.a. swill beer), sit in the hot tub, and look at the high peaks.

Be forewarned: As with all endurance racing, the Breck is addictive. Though I swore I wouldn't, I'm already thinking about the six-day next year. Reason be damned.

—Aaron Gulley