The future doesn’t just happen. The next frontiers of adventure, fitness, gear, and sport are crafted by bold visionaries with world-changing dreams—and the minds and muscles to make them real. Behold the 25 all-star innovators leading us beyond tomorrow.

1. Conrad Anker: High-Altitude Altruist

2. Josh Donlan: Jurassic Park Ecologist

3. Cheryl Rogowski: Organic Genius

4. Bertrand Piccard: Capt. Sun

5. John Shroder: Glacier Watchdog

6. Andrea Fischer: Ice Eccentric

7. Jack Shea: Field Educator

8. Olav Heyerdahl: Upstart Mariner

9. Lara Merriken: Raw Food Guru

10. David Gump: Space Pioneer

11. Dan Buettner: Interactive Explorer

12. Fabien Cousteau: Underwater Auteur

13. Jeb Corliss and Maria von Egidy: Wing People

14. Robert Kunz: New-Wave Nutritionist

15. Colin Angus: Epic Addict

16. Kerry Black: Wave Maker

17. New York City Fire Dept.: Escape Artists

18. Pat Goodman: Aerial Innovator

19. Hazel Barton: Medicine Hunter

20. Alan Darlington: Clean-Air Engineer

21. Richard Jenkins: Speed Demon

22. Olaf Malver: Intrepid şÚÁĎłÔąĎÍřr

23. Al Gore: Media Tycoon

24. Julie Bargmann: Landscape Survivor

25. Daniel Emmett: Hydrogen Hero

Conrad Anker: High-Altitude Altruist

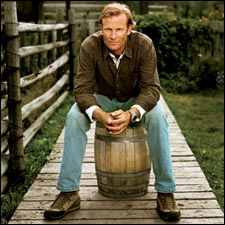

Conrad Anker

HIGHER CALLING: Anker in Bozeman, Montana, where he does work on behalf of the Alex Lowe Charitable Foundation ().

HIGHER CALLING: Anker in Bozeman, Montana, where he does work on behalf of the Alex Lowe Charitable Foundation ().MISSION // IMPROVING THE ODDS FOR SHERPAS

Kicking off our all-stars pantheon, CONRAD ANKER writes that it took the death of his best friend to show him what really counts

ON OCTOBER 5, 1999, THE WORLD AS I PERCEIVED IT CHANGED. I was one of a group of Americans who had traveled to Tibet to ski the immense south face of Shishapangma. As I was traversing a glacier below the 26,289-foot peak with mountaineers David Bridges and Alex Lowe, an enormous avalanche cut loose thousands of feet above us. The churning mass of ice, accompanied by a blast of supersonic wind, swept David and Alex to their deaths. I was thrown 90 feet across the glacier, but by some freak of nature I survived. As I sank into a miasma of guilt, I began to wrestle with the question: Why?

That quickly changed from an analytical evaluation of the avalanche and my actions during the moments before it hit to a more metaphysical line of inquiry. Why had I been given a second chance? And what was I going to do with it? In the wake of the avalanche’s devastation, I realized that I was a different person. I began to ask myself, Who can I help in this new life, and how can I best help them?

These are questions we all need to ask of ourselves—and then turn our answers into action.

Alex had been my closest friend, my climbing partner, my spiritual brother. When he perished he left behind his wife of nearly 18 years, Jennifer, and three young boys: Max, ten; Sam, seven; and Isaac, three. As the five of us mourned our loss, we grew closer. From the ashes of our shared grief emerged an unexpected bond of love like nothing I had ever experienced. In April 2001, Jenni and I were married, and Max, Sam, and Isaac became my sons.

When Alex was alive, he climbed often in the Himalayas, building a special rapport with the Sherpas and other mountain tribes. Inspired by the connections Alex had established in Nepal, and during his other expeditions to Pakistan and Baffin Island, Jenni created the Alex Lowe Charitable Foundation (ALCF) as a way to help indigenous mountain people around the globe. In the spring of 2002, on a trekking trip I’d been hired to guide to Everest Base Camp, Jenni and I would rig top ropes and climb with the Sherpas on nearby boulders and frozen waterfalls. Sherpas have a reputation for being the strongest climbers on Everest—and in fact they almost always are far stronger than any of the foreign climbers who hire them. But most Sherpas have been taught little or nothing about avalanche forecasting, crevasse rescue, or even such rudimentary skills as how to tie into a rope properly. And as a consequence, too many Sherpas die in easily preventable accidents. It occurred to us that one way to make their work less dangerous would be to create a climbing school funded by the ALCF and taught by American mountaineers. Thus the Khumbu Climbing School was conceived.

For two years, our vision guided us through countless hours of planning and fundraising. The passionate commitment of our Bozeman, Montana, community and the outdoor industry came through. In February 2004, Jenni, the boys, and I trekked with fellow ALCF board member and friend Jon Krakauer and six volunteer mountain guides to the Nepalese village of Phortse, a day’s walk above Namche Bazaar, for the inaugural session of the Khumbu Climbing School. We taught our students—many of them high-altitude porters who had completed multiple ascents of Everest and other 8,000-meter peaks—how to inspect equipment, tie knots, place protection, manage ropes, administer first aid, and belay. When that first session concluded a week later, graduating 35 students, our dream was realized.

In the winter of 2005 we held the school again, this time adding an English class to the curriculum; 55 students graduated. In January we expect to graduate more than 100. We anticipate that within a few years we Americans will be able to stay home and let the Sherpas run the school themselves.

Looking back on the avalanche that took Alex from us six years ago, nobody can say for certain why he died and I was spared. The “why” is unknowable. What is important is that out of the tragedy on Shishapangma, I found new purpose. And if one of its results is that fewer Sherpas are likely to perish on the peaks of their homeland—well, for that I would be exceedingly grateful.

Josh Donlan: Jurassic Park Ecologist

MISSION // BRING BACK THE BEASTS

CHEETAHS, MAMMOTHS, AND OTHER LARGE FAUNA once roamed North America, but they disappeared at about the same time humans showed up on the continent. Now, conservationist and Cornell Ph.D. candidate Josh Donlan wants to re-wild the continent—yes, this continent—with their related megaspecies. The 32-year-old former ski-and-climbing bum admits the idea might sound crazy, but he’s not advocating the release of lions—yet. The plan, unveiled in August in the journal Nature and backed by ecology luminaries like Michael SoulĂ©, Paul Martin, and James Estes, is already under way, with the goal of introducing 100-pound BolsĂłn tortoises on Ted Turner’s New Mexico ranches in 2006. Phases two and three are far more ambitious: establishing cheetahs, elephants, and lions on private property, then importing elephants and large carnivores to “ecological history parks” on the Great Plains. Not surprisingly, logistical obstacles like federal and local approval are daunting, and public opinion runs the gamut. “I’ve had people tell me, ‘I’ll quit my corporate job and come work for you,’ ” says Donlan. “And others say, ‘If I see a free-range elephant on this continent, it’ll get an ass full of buckshot, and I’ll kill you, too.’ “

Cheryl Rogowski: Organic Genius

MISSION // REVIVE THE FAMILY FARM

FOR A HALLOWEEN party last year, Cheryl Rogowski got dudded up as Einstein. It was a fitting look for the 2004 recipient of a $500,000 MacArthur Foundation “genius” award. Rogowski, however, is no lab geek—she’s far happier talking apples than atoms. A fourth-generation farmer-cum-agricultural-activist in Pine Island, New York, Rogowski, 44, earned the award for proving that small farms can survive by selling exotic produce to urban consumers with fat wallets and organic sensibilities. The breakthrough idea transformed her family’s 150-acre vegetable farm into an expanding natural-foods empire. “Diversification is the only way we could survive,” says Rogowski. In 1999, she incubated her theories on three acres, planting 15 types of chile and dealing them to New York City’s foodies via community delivery services. The concept took off. She now grows some 250 types of produce. Last year, Rogowski took over the farm and, with money from the MacArthur prize, launched a food label, Black Dirt Gourmet. She’s also begun negotiating a distribution deal with organic-minded supermarket Whole Foods. “We now have the freedom to choose who we sell to, how we sell, and how we grow,” she says. Exactly the way it should be.

Bertrand Piccard: Capt. Sun

MISSION // PILOT A SOLAR PLANE

IN 1999, WHILE DOING THE OBLIGATORY PR prior to his circumnavigation of the earth by hot-air balloon, 47-year-old Swiss adventurer Bertrand Piccard was struck with a radical notion: “I had this idea that the purest way to fly would be with no fuel, no pollution.” Thus began the planning for the Solar Impulse, a plane he hopes will make the first sun-powered round-the-world flight.

It’s an audacious undertaking, considering that the most recent solar aviation milestone was a 48-hour sortie by a radio-controlled craft this past June. To pull it off, he’ll need an extraordinarily efficient plane and a roller-coaster-like flight plan. The single-cockpit, 260-foot-wingspan Solar Impulse, constructed of ultralight carbon fiber, will spend its days climbing to 40,000 feet, then, surviving on 880 pounds of batteries, make slow nocturnal descents to 15,000 feet, just above the cloud layer—any lower and an overcast morning could force a crash landing.

Piccard, whose father took a submersible to the bottom of the Pacific, in 1960, has already raised $15.5 million for the concept. His timeline calls for test flights in 2008, a transcontinental run in 2009, then the four-leg roundabout—with Piccard and two other pilots switching off—in 2010. While the adventure alone is worth the effort, Piccard has a grander vision. “A solar circumnavigation sends a very important message,” he says. “It’s a beautiful symbol for renewable energy and the pioneering spirit of invention.”

John Shroder: Glacier Watchdog

MISSION // ESCAPE THE FLOOD

AFTER 45 YEARS OF TEACHING, most tenured academics are thinking about going fishing. But Shroder, 66, a geography and geology prof at the University of Nebraska at Omaha, is too nervous to slow down. Since 1983, the rock maven has led nearly 20 scientific expeditions to the Himalayas. His frightening discovery? Thousands of the region’s people are living under the threat of imminent global-warming-triggered floods. The danger is caused by “debuttressing,” a process in which rising temperatures cause glaciers propping up near-vertical rock walls to melt until the walls collapse. The resulting domino effect can be lethal: Rockslides dam runoff, forming lakes that swell until they burst and unleash floods on communities downstream. To thwart such disasters, Shroder has set up a warning center in Omaha, where he studies satellite images and alerts Himalayan authorities to coming floods. He’s also coordinating the first workshop between Indian and Pakistani geoscientists. In July, Shroder saw the scenario unfolding near Pakistan’s 28,250-foot K2, where a glacial lake had begun to leak. He says, “Now we’re just waiting for the other shoe to drop.”

Andrea Fischer: Ice Eccentric

MISSION // INSULATE THE ALPS

THESE ARE tough times for Austrian skiers. Their stranglehold on the overall World Cup title was broken last year by the U.S. Ski Team’s Bode Miller, and glaciologists estimate that within 100 years 90 percent of the Alps’ roughly 4,600 small glaciers, which underlie some mountain resorts, will be gone. Enter Andrea Fischer, a glaciologist at the University of Innsbruck and leader of a project that’s putting the melt under wraps—literally. In 2004, with $435,000 in funding from the government and four ski areas, Fischer’s team began covering sections of resorts in the Tyrolean Alps with a one-to-three-millimeter-thick white, fleecelike material. Their conclusion? It works, at least temporarily. On one test plot, the insulation preserved almost five feet of snow, a result that gives Austrian schussers some much-needed hope. “We cannot stop the melting,” says Fischer, “but we can slow it down.” If only they could do the same to Bode.

Jack Shea: Field Educator

MISSION // GREEN THE KIDS

“EDUCATION WITH NO CHILD LEFT INSIDE.” That’s how Journeys School executive director Jack Shea, 54, describes the Jackson, Wyoming–based pre-K–12 program, which combines traditional subjects with environmental projects to nurture a new generation of eco-conscious kids. Under Shea’s leadership, Journeys—founded in 2001 as an offshoot of the Teton Science Schools—now has a new campus to match its green philosophy. The $23 million project, which wrapped in September, features recycled-tire carpeting, buildings sited to receive maximum solar radiation, and 880 acres of open space. The facility will act as a lab for the Teacher Learning Center, a residential program that trains educators from around the world in Journeys’ experiential curriculum. “Everyone likes to complain about education,” says Shea, “but we enjoy actually doing something about it.”

Olav Heyerdahl: Upstart Mariner

Olav Heyerdahl

RESPECT YOUR EDLERS: Heyerdahl aboard the legendary Kon-Tiki, in an Oslo museum.

RESPECT YOUR EDLERS: Heyerdahl aboard the legendary Kon-Tiki, in an Oslo museum.MISSION // RAFT THE PACIFIC

IF YOUR GRANDFATHER is one of adventure’s most celebrated mavericks, taking any expedition is perilous for the ego. Such is the predicament of 28-year-old Oslo, Norway–based Olav Heyerdahl. In 1947, his grandpa Thor and five fellow Scandinavians drifted 4,300 miles, from Peru to Polynesia, on the balsa raft Kon-Tiki to prove that the South Pacific could have been settled by pre-Inca mariners. Academics dismissed the stunt, but the 101-day journey ignited a raucous popular debate about Polynesian history and catapulted the amateur anthropologist into the spotlight—exactly where Heyerdahl hopes to find himself next April, when he and five other explorers launch a bid to re-create the journey. What can we learn from the reenactment of a legend? A lot—as DAVID CASE discovered when he caught up with the aspiring mariner.

OUTSIDE: How will your journey differ from the Kon-Tiki expedition?

HEYERDAHL: For starters, we’ll build the raft my grandfather would have built if he was setting out today. We’re adding a system of centerboards that archaeologists now believe the ancient Peruvians used to steer, rather than float with the currents. We’re going to navigate to Tahiti—not just crash into a reef like the Kon-Tiki.

What will you do all day?

I’m the expedition diver, so I’ll be taking under-water photos, plus taking shifts steering and cooking. We’re going to gather data about marine organisms and currents. A slow-moving raft is like a mini coral reef—as barnacles colonize it, the fish come to feed, then come sharks, and so on. So we can really study the life up close and then compare our observations with my grandfather’s. Also, a fisheries biologist will take water samples. He’s researching drifting pollutants that are changing the sex of fish.

How will you get the word out?

We’ll be filming a documentary to alert people to the drastic changes over the last 50 years, both in the ocean and on land. The jungle where my grandfather got his wood for the raft has been overrun by a city of 130,000, and the river he used to float the logs to the Pacific has all but dried up.

So will you still use balsa wood?

Yes, but we’ll have to buy it from a plantation.

Isn’t it a bit flimsy for an ocean crossing?

Actually, it’s virtually indestructible. A fiberglass boat might sink if it gets a hole, but a balsa raft can lose two-thirds of its hull and stay afloat. The biggest threat is an attack by shipworms—they can eat the whole thing.

Six guys on a small raft for 100 days sounds rough.

We’re planning to have a quiet spot—a base where you can just sit there and shut up and no one will bother you.

Do you have any experience building rafts?

No, but it’s the same situation as my grandfather in 1947. At least I’m a carpenter.

Have you ever even been on one?

The Kon-Tiki, but only in a museum. It wasn’t very dangerous.

Lara Merriken: Raw Food Guru

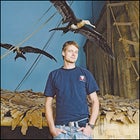

Lara Merriken

MISSION // RAISE THE BAR

A FORMER CHIPS-AND-SODA DEVOTEE, Merriken found the path to enlightened eating when her University of Southern California volleyball coach laid down a no-sugar mandate. “I suddenly had consistent energy and more mental clarity,” recalls the 37-year-old Denver native. “No more of those crazy highs and lows.” In 2000, a decade after retiring her kneepads, Merriken, an avid runner and hiker, had her “Aha!” moment: Apply the same sugar-free strategy to energy bars by concocting an all-natural, raw-food snack with no baking, processing, or preservatives. Three years later—after countless hours whirring dried cherries, dates, cashews, and other raw nuts in her Cuisinart—she shipped her first batch of LäraBars to health-food stores in Colorado. They were an instant hit with endurance junkies looking for an organic, longer-lasting buzz: In less than two years, her company has become a $6 million business, with sales in all 50 states, Mexico, the UK, and Canada. Says Merriken, “Now I’m thinking about entirely new foods we can create with the same philosophy.”

David Gump: Space Pioneer

MISSION // BLAST OFF ON A BUDGET

“I READ A LOT OF SCIENCE FICTION when I was younger but had no intention of a career in space,” says David Gump, 55, the cofounder and CEO of Reston, Virginia–based Transformational Space Corporation, or t/Space. Today, the onetime railroad lobbyist is blazing a trail to the solar system with a low-cost plan to launch manned expeditions to the moon and Mars. His far-out proposition: a transportation chain that breaks the trip into stages. First, get astronauts into orbit—the most difficult part of any space voyage—with a reusable rocket-propelled capsule. Next, transfer to a parked spacecraft to make the haul to the moon or Mars.

By breaking from the one-ship model, Gump’s strategy makes for a highly efficient R&D process—and saves a bundle. This past spring, his team unveiled a mock-up of their reusable crew-transfer vehicle, the CXV, which can carry four astronauts into orbit for a paltry $20 million per flight (a shuttle flight typically tops $1 billion). Starting in May, he ran a 23-percent-scale prototype through a partial test of the first stage of the launch sequence. (On an actual mission, a jet would release the CXV at 50,000 feet and rockets would then blast the vehicle into orbit.)

Though t/Space now needs to raise $400 million (likely in the form of a NASA contract) to complete a space-ready CXV, Gump is already one giant leap closer to his goal, having demonstrated the potential to get into orbit without breaking the bank. “Once you get off the planet,” he notes, “you’re halfway to anywhere in the solar system.”

Dan Buettner: Interactive Explorer

MISSION // LIVE FOREVER

HE’s BIKED MORE THAN 120,000 MILES around the globe and is considered the father of the interactive expedition, but Dan Buettner may be on the verge of his greatest feat to date: unlocking the secret to long life. In 1992, Buettner and three other cyclists pedaled across the Sahara to the southern tip of Africa to promote racial awareness—posting their travels on Mosaic, an early Internet browser. The St. Paul, Minnesota–based Buettner, 45, has since launched 12 real-time expeditions designed to enlist Web users to help solve some of science’s biggest questions. For his latest Quest (), he has narrowed down the globe’s “blue zones”—hot spots of human longevity—and is working with top demographers and physicians to study diet and lifestyle and create a blueprint for living longer. First stop: Okinawa, Japan, followed by mountain villages on an as-yet-undisclosed island in the Mediterranean. “We know that there’s a recipe for longevity, and that 75 percent of it is related to lifestyle,” he says. “And we’re figuring it out.”

Fabien Cousteau: Underwater Auteur

Fabien Cousteau

DIVE MASTER: Cousteau on board at New York City’s Dyckman Marina.

DIVE MASTER: Cousteau on board at New York City’s Dyckman Marina.MISSION // SAVE THE SEAS

FABIEN COUSTEAU IS SUNBURNED. It’s a sultry August evening in Key Largo, Florida, and the 38-year-old grandson of history’s preeminent undersea explorer arrives late for dinner, having just wrapped up a 13-hour day filming coral spawning. He walks across the parking lot of the Italian bistro and extends his hand to shake mine. His wispy brown hair is flecked with gray, a striking contrast to his crimson face. “I’m Fabien,” he says. “I’ll be right back.” With that, he darts across the blacktop highway in his flip-flops and into a CVS pharmacy. Five minutes later, he returns clutching a jumbo bottle of aloe vera gel.

So it goes for Fabien, a skilled underwater filmmaker with ambitious plans for the First Family of the Deep. After about 12 years of career roaming—freelancing as a graphic designer and marketing eco-friendly products for Burlington, Vermont–based Seventh Generation—he’s looking to breathe new life into his clan’s once pacesetting documentary juggernaut and shake up a public that he believes is inured to the rapidly declining health of the world’s oceans. His strategy: Ditch the classic Cousteau marathon approach to filmmaking in favor of fast-moving production teams that can deftly churn out television specials defined by modern visual fireworks and high-paced editing.

If he can shake off his land legs—SPF 40, anybody?—he’s well suited to the challenge. Fabien, who was raised in the States, took his first plunge with a scuba tank at four and began joining family filming expeditions aboard the Calypso at seven. In his teen years he regularly pitched in with documentary crews working for his father, Jacques’s oldest son, Jean-Michel, and his grandfather. But while coming of age in flippers infused him with a profound connection to the sea, adulthood brought with it a craving to venture beyond his family ties. “After college, I went through a rebellious phase and thought I would do something different,” says Fabien. This led him into a spate of business courses, the gig with Seventh Generation, and treks in Nepal and Africa.

His rediscovered commitment to the family legacy grew out of a gnawing sense of responsibility to the seascapes that were once his playgrounds. “I feel an urgency that maybe my grandfather didn’t until his later years,” he says, “to explore faster and faster before the oceans are destroyed so you can then relay the message to the general public and they can influence what’s happening.”

Though his surname provides a leg up in any film project, Fabien faces a ruthless broadcast landscape Jacques Cousteau never could have imagined. “When Jacques was on television, there were fewer than ten channels,” points out Jean-Michel, 67. “In the 1970s, we’d have 35 million Americans watching all at once on ABC. That’s unthinkable today, unless it’s the Super Bowl.”

Fabien also has to contend with a fractured Cousteau dynasty. In 1990, shortly after Jacques’s first wife died, the 79-year-old patriarch confessed to a long affair with Francine Triplet, a Frenchwoman 40 years his junior. Jacques married her a year later, and Jean-Michel was swept aside as his stepmother took over his duties within the Cousteau Society. After Jacques died, in 1997, Francine was named president of the Society, which owns all commercial rights to the Cousteau name and his work; Jean-Michel agreed not to use “Cousteau” to promote his own ventures unless he directly precedes it with “Jean-Michel.” And while he’s released more than 70 of his own blue-chip TV documentaries, he’s never attained Jacques’s megastardom—a fact that’s left the next-generation Cousteaus lingering backstage.

All this means that Fabien is going to have to succeed on his own passions and talent. It does appear that he has plenty of both. His emergence began in 2000, when he joined Jean-Michel on a filming expedition to South Africa. Two years later, National Geographic hired him to host a special on the legendary 1916 Jersey Shore shark attacks. This fall, Fabien completed his first self-produced project, Mind of a Demon, which debunks the notion that great white sharks are ruthless killing machines with a taste for humans. He enlisted Hollywood inventor Eddie Paul to build a 14.5-foot submarine that looks and swims like a great white. Dubbed Troy, it allowed Fabien to capture never-before-seen footage of the predators dueling for territory off Mexico’s Pacific coast. Despite a budget of only $650,000, the one-hour film premiered on CBS in November—the first network airing of a Cousteau documentary in more than a decade.

He’ll be onscreen again next spring in Ocean şÚÁĎłÔąĎÍřs, Jean-Michel’s new six-hour PBS series, which mixes celebration of undersea beauty with reporting on the plight of marine ecosystems. Fabien plays a starring role in the final two-hour episode, which explores America’s national marine sanctuaries. The series also unites him for the first time on television with both his 33-year-old sister, CĂ©line, and Jean-Michel; KQED Public Broadcasting in San Francisco, the project’s co-producer, has dubbed it “the return of the Cousteaus.” Fans drawn by that pitch might be surprised by the thumping soundtrack and reality-TV format, with crew members and sea critters getting equal camera time—a result, to some degree, of Fabien’s preproduction suggestions and editing-room tinkering.

Blending environmental gospel with pop entertainment is tricky business, but Fabien argues that it’s essential to jump-start ocean conservation in an era of 400 cable channels and Desperate Housewives. And if you’re going to lure people into caring about the undersea world, it helps to roll out its biggest stars, which is why he’s planning documentaries on blue whales and the giant squid. “The Cousteaus have always been a voice for the sea,” he says. “This is what I’ve inherited: the responsibility of exploring and protecting the oceans.”

Jeb Corliss and Maria von Egidy: Wing People

MISSION // FLY LIKE A BIRD

THE RACE TO BE THE FIRST to jump out of a plane and land safely without deploying a parachute is on. That’s the goal of Malibu-based Jeb Corliss, 29, and South African Maria von Egidy, 41, who, working separately and in secret, say they’ve found a way for humans to leap from 30,000 feet and live—wearing flying-squirrel-like wingsuits that slow free fall to less than 40 miles per hour while propelling you forward at more than 100 miles per hour. This can make for a rough landing, but BASE jumper Corliss claims to have invented a touchdown strategy that “can be done ten times out of ten without breaking a fingernail.” Meanwhile, von Egidy, a former costume designer, says she’s within a year and $400,000 of skydiving’s ultimate prize; now all she needs is a willing test pilot. “Obviously,” she says, “it will have to be someone very brave.”

Robert Kunz: New-Wave Nutritionist

Robert Kunz

MISSION // LAST LONGER

AFTER A DECADE in the endurance-supplement industry, Charlottes-ville, Virginia–based nutritionist Robert Kunz, 36, was fed up with taking directions from boards made up of doughy scientists and following a market-based approach to development, which begins with a price point and ends with a mediocre powder or pill. So in 2002 he launched First Endurance with a revolutionary mandate: Create supplements conjured exclusively by endurance athletes—and ignore the cost. An amateur triathlete, Kunz staffed the company—from the lab geeks to the legal counsel—with fitness junkies, then asked for their biggest ideas. The subsequent brainstorms have produced supplements that deliver on their promise, thanks to clinically proven dosages of endurance-boosting ingredients. Their inaugural Optygen, composed of herbs and fungi that speed recovery, costs $50 for a month’s supply—$10 more than competitors—yet boasts a 99 percent repeat-customer rate. “We know athletes,” says Kunz. “We had a good idea this would work.”

Colin Angus: Epic Addict

MISSION // CIRCLE THE EARTH

IF YOU’RE LOOKIGN TO AMP UP INTEREST in alternative transportation, there are plenty of strategies easier than attempting the first human-powered lap of the planet. Canadian explorer COLIN ANGUS, 34, is aware of this, but he also knows that it might take a remarkable statement to inspire people to reconsider their lifestyles. This recent dispatch sure had us thinking twice about our morning commutes.

FROM: COLINANGUS // TO: OUTSIDEMAG // SUBJECT: EXPEDITION PLANET EARTH // DATE: SEPTEMBER 21, 2005 5:55:18 AM EDT

My travel partner and fiancĂ©e, Julie Wafaei, and I have just reached Lisbon, Portugal. Time is tight; tomorrow morning, we trade our bikes for a rowboat to commence a 5,200-mile, four-month row across the Atlantic. We’re actually looking forward to relaxing in the boat some, as I’m feeling a little tired.

Circling the globe on human power really drives home just how big this planet is and how important it is to reduce greenhouse emissions. My expedition began June 1, 2004, from Vancouver. Since then, traveling with several different partners, I’ve cycled and canoed through Canada and Alaska, rowed the Bering Sea, and trekked, skied, and biked 14,000 miles across Eurasia. In Siberia, I got separated from my former teammate, Tim Harvey, and spent the night in a snow cave; outside it was 49 below zero with 40-mile-per-hour winds.

Now as I look out at the empty blue sea separating Europe and North America, the world is looking even bigger.

Cheers, Colin

Ěý

Kerry Black: Wave Maker

MISSION // SURF INDOORS

WITH A LEGENDARY point break off his home in Raglan, New Zealand, Kerry Black has little need for artificial waves. But the 54-year-old Ph.D. oceanographer, who’s spent more than 20 years computerizing wave mechanics, is creating a wave pool that could be the biggest development in surfing since the wetsuit. Scheduled for completion in Orlando, Florida, as early as next summer, the Ron Jon Surfpark promises to pump out peaks with the power and shape of natural waves—a major achievement, considering that the hundreds of current wave pools deliver mushy rollers. Black’s design has compressed air forcing thousands of gallons of salt water down a 300-foot-long basin with converging sidewalls, which preserve the wave’s height (up to eight feet), while steel triangles on the bottom can be adjusted to mimic the reefs under 40 of the world’s great breaks. New Jersey–based Surfparks, which licensed the concept, has raised $10 million for the park, while some 4,000 surfers stoked for predictable swells are on a waiting list for annual memberships (up to $2,400). “Surfers will still travel to waves around the world,” says Black, “but I reckon the future of the sport is twice as big now.”

New York City Fire Dept.: Escape Artists

MISSION // STOP, DROP, AND RAPPEL

“THIS IS THE WORST DAY OF YOUR LIFE,” says New York City firefighter Bill Duffy, 40, describing the jump-or-die scenario that inspired a revolutionary new escape device that’s set to become standard issue for Gotham’s hook-and-ladder heroes. “It’s get out the window as fast as you can.” Last January, Duffy was part of a team of FDNYers-cum-designers who set out to make a lightweight system to enable an emergency exit from almost any window. Borrowing a few rock-climbing tricks, the Batbelt-like units, which pack into a bag on a firefighter’s hip, feature a nylon harness, 50 feet of flame-resistant rope, a descender, and a single sharpened hook based on a prototype forged in the FDNY shop. Surrounded by flames, a fireman can slip the hook around a pipe, or jam its point into any solid surface, then roll headfirst out a window. The descender, a modified version of the Petzl Grigri, catches when weight hits the rope, allowing a controlled descent. The city is spending $11 million for 11,500 kits and training, which began in October, but, says Duffy, “hopefully, they won’t ever get used.”

Pat Goodman: Aerial Innovator

MISSION // CRACK OPEN KITEBOARDING

GOODMAN, CHIEF DESIGNER at Maui-based kiteboard manufacturer Cabrinha, was determined to help beginners master the sport’s toughest skills: staying in control during big gusts and relaunching after wipeouts. This past July the 49-year-old unveiled the Crossbow system, which may do for kiteboarding what parabolics did for downhill skiing. The Crossbow pairs a nearly flat kite—more akin to a plane wing than to its U-shaped predecessors—with a rigging that dramatically boosts power and control: Nudge the steering bar outward to slam on the brakes. Tug on a rear line after a fall and the kite fires aloft like a rocket. “I wanted to be able to get my ten-year-old daughter into the sport,” says Goodman. “Now I can—if she’d just stop windsurfing.”

Hazel Barton: Medicine Hunter

MISSION // CAVE FOR THE CURE

SHE MAY SEEM AN UNLIKELY SAVIOR—with a map of a South Dakota cave tattooed on one biceps, a well-behaved women rarely make history bumper sticker on her truck, and a starring role in the 2001 Imax film Journey into Amazing Caves. But Barton, a 34-year-old Northern Kentucky University biology professor, is one of the best hopes for finding new antibiotics that could potentially save hundreds of thousands of lives each year. And she’s searching underground. While the de facto scientific opinion holds that caves are microbiologically barren, Barton’s research, conducted from Central America to Appalachia, has proven otherwise: Most are teeming with microorganisms armed with antibiotic weapons. To harvest them, Barton—who was born and raised in Britain—squirms through shoulder-wide passageways and rappels several stories into black pits, armed with a stash of microprobes, test tubes, and cotton swabs. Back in the lab, it may take months to extract the antibiotic agents, then years longer before effective drugs can be developed. But fortunately Barton—who’s now scouting a secret cave in Kentucky for an antibiotic to knock out a nasty drug-resistant, tissue-dissolving strain of the common staph infection—is in it for the long haul. “Population control should be done through education and policy, not human suffering,” she says. “As long as tools are available to reduce that suffering, I’ll try to find them.”

Alan Darlington: Clean-Air Engineer

MISSION // BREATHE EASIER

THE BAD NEWS: ACCORDING TO EPA estimates, indoor air can be five times more polluted than the air outside—and Americans spend an average of 90 percent of their time inside. The good news: Filters made from plants—which host toxin-digesting microbes—can help create purer air. Canadian biologist Alan Darlington, 46, helped come up with the idea in 1994, at Ontario’s University of Guelph, while researching air-filtration strategies for the Canadian and European space agencies. Nine years later, he built his first commercial biowall—a polyester-mesh structure embedded with plants like orchids and bromeliads—which reduces some pollutants by as much as 95 percent. Now Darlington’s company, Guelph–based Air Quality Solutions, has manufactured eight 32-to-1,500-square-foot walls in Canada and installed the first U.S. wall at Biohabitats, an environmental-restoration firm in Baltimore, this past September. What’s next? Biowalls small enough for private homes, which Darlington hopes to unveil in 2007.

Richard Jenkins: Speed Demon

MISSION // RIDE THE WIND

IF RICHARD JENKINS were a betting man, his trifecta would be 116, 143, 56. Those are the respective wind-powered land, ice, and water mile-per-hour speed records the 29-year-old Brit is on the verge of breaking. For the past five years, Jenkins, a mechanical engineer and amateur glider pilot, has built three crafts—on wheels, skates, and hydrofoils—equipped with rigid carbon-fiber sails. The sails, which can tack 35 degrees to either side, act like vertical airplane wings, providing forward motion instead of lift. They offer minimal acceleration in low winds but a serious speed boost in gusts over 50 miles per hour. The land craft unofficially broke records during testing in the UK in 2002, hitting 125 miles per hour, and Jenkins is planning another run at a dry lake bed in Nevada. This winter, he’ll sail his ice vehicle on frozen lakes in Wisconsin in a bid for the 67-year-old record. But beating a dozen competitors out for the water title may be his most daunting challenge. “If I thought my chances were marginal,” says Jenkins, “I wouldn’t be here. I’m just waiting for that one windy day.”

Olaf Malver: Intrepid şÚÁĎłÔąĎÍřr

MISSION // GET LOST

“WE DON’T KNOW WHAT THE HELL WE’RE DOING, so let’s go! Let’s find out what we’re doing!” So says 52-year-old Danish explorer Olaf Malver, of the philosophy behind Explorers’ Corner, his Berkeley, California–based travel company, which guides clients on adventure explorations around the world, from paddling in tropical Indochina to trekking in the Republic of Georgia. While larger outfitters might offer one untested itinerary a year, Malver—a 24-year adventure-industry veteran who speaks six languages and holds a Ph.D. in chemistry and a master’s in law and diplomacy—is convinced that his seat-of-the-pants approach is what travelers now crave. “We’re sharing the exploration with co-explorers, not just dragging them around,” he says. “We don’t cater. We demand involvement. Plus we’ve already told them that we don’t know what we’re doing, so when we get into trouble, they take it with a smile.”

Al Gore: Media Tycoon

MISSION // DEMOCRATIZE TV

AL GORE APPEARED TO BE ON LIFE SUPPORT after his failed 2000 presidential bid: He bounced between jobs teaching journalism and a few fiery speeches before vanishing from the public eye. Now the 57-year-old ex-veep is back, resurrected as the visionary and chairman of San Francisco–based Current TV, a four-month-old cable network that depends on viewer-created content for more than a quarter of its programming. “Current enables viewers to short-circuit the ivory tower and provide the news to each other,” says David Neuman, president of programming. “It’s revolutionary.” Like an on-air blog, Current encourages aspiring Stacy Peraltas armed with digital camcorders and PowerMacs to shoot and edit short videos; then visitors to the network’s Web site vote on what gets aired. Some, like “Jumper,” a fast-paced homage to BASE jumping that mixes helmet-cam footage and interviews with an amped-up soundtrack, are cool; others are predictably awful. It’s a bold idea for the notoriously unhip Gore, but Al (as he’s known around the office, where he has been heard inquiring about the network’s “street cred”) has brought to Current more than an A-list name and access to deep pockets. “He wants to democratize television,” says Neuman. And, in the process, he just may recast himself.

Julie Bargmann: Landscape Survivor

MISSION // RESURRECT THE WASTELANDS

AS ONE OF THE LEADING landscape architects specializing in revitalizing toxic Superfund sites and derelict brownfields, Julie Bargmann is a sort of fairy godmother of industrial wastelands. “Most remediation projects are just lipstick on a pig,” she says. “They truck the dirt to New Jersey and slap a parking lot over the site.” Which is why the 47-year-old started D.I.R.T. (Design Investigations Reclaiming Terrain) Studio, in Charlottesville, Virginia. Bargmann seeks out nasty places from Israel to Alaska, hires scientists to pitch in with the eco-cleanup, and transforms blight into beauty. Results so far include the makeover of a basalt quarry into a thriving vineyard and wildlife habitat in Sonoma County, California. “Postindustrial landscapes are bound to become central to many of our communities,” says Bargmann, “and reclaiming these derelict sites is a way to contribute to communities and the environment.”

Daniel Emmett: Hydrogen Hero

MISSION // FUEL AN ENERGY REVOLUTION

IT’S THE LIGHTEST, MOST ABUNDANT ELEMENT IN THE UNIVERSE, can be derived from a stalk of celery or a lump of coal, is twice as efficient as gasoline, and has only two by-products: water vapor and heat. No wonder hydrogen is the next big thing in alternative fuels—and car-crazed California is its testing ground. Leading the charge is Daniel Emmett, 36-year-old cofounder of the Santa Barbara–based nonprofit Energy Independence Now. In 2001 Emmett partnered with green politico Terry Tamminen to create a network of hydrogen-fuel stations along California’s 45,000 miles of roadway. They pitched the idea to anyone willing to listen; in 2004 Governor Schwarzenegger pledged support, ponying up $6.5 million in state funding in 2005. Now there are 17 hydrogen stations across the state, and Emmett is pushing for a total of 100 by 2010 as part of a larger effort to reduce petroleum dependency and cut greenhouse-gas emissions by 30 percent. It’s a tall order: There are currently only 70 hydrogen test vehicles on California roads (though the major auto manufacturers are racing to develop new fuel-cell technologies), and Emmett estimates he’ll need another $54 million. But the hydrogen revolution has to start somewhere. “If we don’t do something today,” says Emmett, “it’ll always be 30 or 40 years off.”