One score and five years ago, this magazine burst onto the scene with a bold idea and a mission. The idea was that, against all odds, adventure is alive and well—and a force to reckon with and celebrate. The mission was to find new heroes, phenomenal athletes and explorers, the men and women whose creative force keeps the cutting edge of adventure moving toward the far horizon.

Flash forward to this grand-finale issue of our silver-anniversary year, and we’re still excitedly staking our claim on the future, still celebrating the bracing shock of the new. Which brings us to the 25 amazing, inspiring, wild-eyed young stars in the pages that follow. None had even been born back when ���ϳԹ��� was launched—but we guarantee you’ll be hearing a lot about their exploits and achievements during our next quarter-century. They’re the rising generation, they’re the real deal, and they’re not going anywhere but up. Meet the faces of tomorrow.

Climbers

Beth Rodden

Rodden in Tommy Caldwell’s van, Yosemite National Park

Rodden in Tommy Caldwell’s van, Yosemite National ParkBeth Rodden [22]

[ROCK CLIMBER]

Estes Park, Colorado

The answer is yes: There is life after Kyrgyzstan for Beth Rodden. “Man, I’m excited about everything,” she says. The young climber, best known for surviving the high-alpine hostage crisis of 2000 that was chronicled by Greg Child in these pages (“Fear of Falling,” November 2000) and in the subsequent book Over the Edge, is back. In February, Rodden got engaged to sweetheart Tommy Caldwell, who had been at her side in Kyrgyzstan, and celebrated the occasion by becoming the first woman to climb Grand Illusion (5.13c), a single-pitch crack at Sugarloaf, California. Then, in May, she shook off the nightmare-wracked funk she had been experiencing after the kidnapping with an impressive on-sight of Phoenix (5.13a), a crack in Yosemite. It was the final step on the road to mental recovery that had begun in October 2001, when she and Caldwell joined 11-year-old California rock prodigy Scott Cory on a Yosemite climb that raised $10,000 for the families of 9/11 rescue personnel.

“I never stopped climbing after Kyrgyzstan, but I stopped having goals,” Rodden says. “Really, I just did it because I felt like I was supposed to—that climbing was my job. But I wasn’t having fun. I felt like climbing was selfish, that I wasn’t doing anything worthwhile. Doing the thing with Scotty definitely changed my view.”

Her upcoming projects, conspicuously, don’t involve dusting off her passport. “Honestly, yeah, I’m scared to travel to Third World countries right now,” she says. “But I’m pretty psyched to challenge myself around home. There’s plenty to do here.” —Eric Hagerman

Tori Allen [14]

[CLIMBER]

Indianapolis, Indiana

They said Tori Allen would grow out of her precocious talent. They were wrong. Last year this 95-pound crowd-pleasing monkey child skipped into young womanhood without losing a step. Triumphs at the Gorge Games (in bouldering, for the second straight year) and the X Games (she smashed the women’s speed-climbing world record by nearly four seconds) capped a year in which she won the American speed-climbing championship and became the youngest woman to climb The Nose of El Capitan. After claiming two straight junior national titles, the 14-year-old homeschooled phenom, who accessorizes with a trademark Curious George doll clipped to her chalk bag, jumped to the adult circuit last year and quickly challenged 27-year-old bouldering champion Lisa Rands.

“The first time I beat Lisa, I was like, whoa,” says Allen, who as a toddler literally climbed with monkeys in the jungles of Africa as her missionary parents egged her on. “Since then we’ve both gotten stronger and it’s back and forth, back and forth.” With half a dozen sponsors, a slick Web site (), and the occasional spot on NBC’s Today, Allen’s professional gloss has led to hand-wringing among some climbing purists, who aren’t used to perky 14-year-old superstars. “Tori’s the first step to selling out the sport,” one critic carped in an online discussion group. Allen shrugs it off. “I love that feeling, competing and being in the spotlight,” she says. “Not to be a brat or anything, but it’s really fun.” —Bruce Barcott

Miles Smart [22]

[SPEED CLIMBER]

Seattle, Washington

When Miles Smart grabs a fistful of granite and begins pulling himself up one of Yosemite’s big walls, his stocky, rock-solid body gobbles up the vertical with a poetic economy of motion. The same strident efficiency shines through when he returns to level ground: “I love being able to climb a big route in a day and be back in the Valley in time for dinner.”

Born in Seattle, Smart started climbing glaciers when he was nine years old. By age 17 he’d topped out on El Cap three times; by 18, he’d done it eight times. But Smart’s speed jones didn’t emerge until the next year, 1999, when he and several buddies pulled off multiple single-day ascents of Yosemite routes that most rock jocks complete in three to five days. Over the next couple of years, he set ten speed-climbing records in the Valley. One of those feats, a nine-hour 15-minute ascent of Zodiac (5.10) in 1999, drew considerable flak from his peers, including big-wall godfather Dean Potter (see “Climbing at the Speed of Soul,” page 98), when it was revealed that, over two pitches, he had briefly protected himself with ropes set by other climbers. (The shortcut, which he admits he did not initially disclose in interviews, shaved precious minutes off his time.) “He’s moved on,” says friend and former mentor Mark Kroese, 41. “All of these speed climbers have some dirt on them.”

Despite the bad press, Smart isn’t about to put away the stopwatch, and he’s also dabbling in ski-mountaineering. “I climb up difficult mixed routes and try to ski down them,” he says. In 2000, that meant a descent of Gervasutti Couloir on the Mont Blanc du Tacul face, near Chamonix, France—a 55-degree maze of ice, rock, and snow. The face was so steep that Smart hesitates to call it a ski line. “It was more like a climbing route,” he says. “There wasn’t much snow. You had to tickle your way down.”

These days Smart divides his time between Yosemite, the mixed routes and steep couloirs outside Chamonix, and Valdez, Alaska, where he pays the bills as a heli-ski guide. But upward velocity remains his first love. “He’s fast at everything,” says Kroese. “He hikes fast; he climbs fast. He’s just fast.” —Brad Wetzler

The Pulse (Cont.)

By the Numbers

RECOVERY

A KNIFE ALTERNATIVE

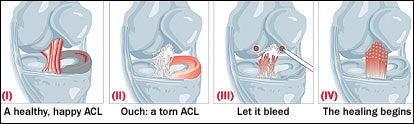

Skier Bode Miller was only one year removed from a torn ACL when he won silver in the Salt Lake Games. The key to his rapid return was a new arthroscopic procedure called the “healing response,” pioneered by Dr. Richard Steadman of the Steadman-Hawkins Clinic in Vail, Colorado, in 1999. Instead of total ACL reconstruction, Steadman pokes anywhere from three to 16 small holes in the femur above the torn ligaments (III). When the bleeding bones begin to heal naturally, the resulting blood clot captures and heals the torn ACL as well (IV). Bam! Like Miller, the patient can be completely mobile in three weeks. Miraculous? Yes, but only ripped ACLs with a tear at or near the femur qualify. Still, Dr. William Rodkey, director of Basic Science at Steadman-Hawkins, states optimistically, “This is an alternative to full reconstructive surgery that works.”

11: percentage difference in distance traveled by athletes while listening to Metallica during a ten-minute bike ride, over those who sweat in silence, according to a Hampden-Sydney College study in Virginia last spring. Don’t like metal? Have no fear. “Picking music you like is a more important factor in boosting performance than just music with a faster tempo,” says Robert Herdegen, professor of psychology at Hampden-Sydney. In other words, if Beethoven rocks your world, plug him in and fly.

Skiers

Miller at home in Franconia, New Hampshire

Miller at home in Franconia, New Hampshire

Bode Miller [25]

[ALPINE SKIER]

Franconia, New Hampshire

Like 100-meter sprinters, the top finishers in Olympic and world slalom races are separated by only hundredths of a second. So when Bode Miller began winning last season by one, two, even three seconds, the slow-motion videos started rolling in race rooms across Europe, as coaches and athletes attempted to reverse-engineer his runs. “The average Joe couldn’t see anything different in my style,” says Miller. “Only the top racers in the world can notice the little things, like how I pressure the ski, turn shape, and stance.”

Good luck to them: This guy really wins by pure explosiveness. His biggest problem—if someone who took home two silver medals from Salt Lake City has a problem—is that he’s too fast. Until recently, the 210-pound powerhouse crashed out on more courses than he finished. To destroy the competition last season, he had to dial it back.

Not that all those yard sales stymied Miller’s confidence. A talented multisport athlete, he has claimed that he could have played pro tennis or challenged Brazilian great Ronaldo in soccer. Of course, it’s tough to argue with a guy who medaled in ten World Cup races last season, and then in May flew off to Jamaica to spank Jonny Moseley and a slew of NFL talent in the made-for-TV celebrity competition known as Superstars. The key to Miller’s success? He didn’t trip in the obstacle course. —Marc Peruzzi

Sarah Clemensen [24]

[TELEMARKER]

Salt Lake City, Utah

Most freeheelers don’t willingly huck themselves off 25-foot cliffs. Fewer still will throw in a flip for good measure. But the five-foot-ten, 165-pound Sarah Clemensen isn’t your average telly chick. “I have aggression, speed, and a crazy look in my eye, yet I still have grace, fluidity, and a girly swing,” she says, with characteristic swagger. That Speed Racer gaze has been with her from her first competition, the U.S. Nationals at Washington’s Stevens Pass in 1999, where—despite having never before bashed the bamboo—she clinched the expert division. Four years later, she’s the only member of the U.S. Telemark Association’s national team who also dominates the U.S. Freeskiing Series. And she’s only going bigger. Just ask filmmaker Josh Murphy, who invited her to carve blistering turns for his September-released flick Unparalleled 3: Soul Slide: “She’ll blow up on a mountain before she’ll inch down it.” —Eric Hansen

Runner

Moehl at the Seattle Center

Moehl at the Seattle Center

Krissy Moehl [25]

[ULTRARUNNER]

Bow, Washington

Every night before the 50-mile torture test that ultrarunners call a race, Krissy Moehl paints her toenails. Each nail receives a minimum of three colors and is topped with sparkles. “It helps me relax,” says the former University of Washington track team walk-on. Evidently, the ritual is paying off. In March 2000, just three months after four-time Western States 100 winner Scott Jurek invited her along on his group training runs outside Seattle, Moehl torched the women’s field at her first ultra—the Chuckanut 50K in Bellingham, Washington—and set a new course record of just over five hours. She’s since won six more ultras and has finished out of the top three only once in her last ten races. How does this five-foot-seven prodigy thrive in a sport dominated by runners in their late thirties and early forties? “She’s got phenomenal natural endurance ability,” says ten-year ultra vet Scott McCoubrey, 40, “and an extremely high tolerance level for pain and suffering.” —Michael Roberts

Cyclists

Bahati drops the hammer

Bahati drops the hammer

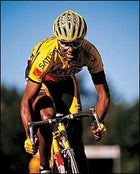

Rashaan Bahati [20]

[ROAD CYCLIST]

Los Angeles, California

“Five, four, three…” Rashaan Bahati is in a Colorado Springs lab, pedaling a road bike on a trainer set to zero resistance. “Two, one…huh!” A technician throws a lever connected to the racer’s cranks. It’s as if Bahati had rounded a corner and plunged into a pool of wet cement. The friction is unbearable. Or it would be for most. Bahati, a sprinting prodigy, churns cement to froth.

Six feet tall and 156 pounds, Bahati seems tailor-made to dominate the sprint finishes of road races. At 18 he won the 2000 Junior National Criterium and the Junior National Road Championships, and then went out and beat up on the best sprinters in the country, taking first in the Elite Senior National Criterium Championships in Downers Grove, Illinois. “When you see someone do something unbelievable early in his career, that’s enough,” says Team Saturn coach Jim Copeland, who signed Bahati to his road-riding crew shortly thereafter. “He pretty much showed everybody that he’s the fastest junior out there.”

Of course, smoking a field of Americans is one thing; European stage races like the Tour de France and one-day Spring Classic events like ParisÐRoubaix are another. To win those events, riders must sprint after a grueling 100-mile-plus grind. Balancing endurance (for hanging in the peloton) with speed (for matching the world’s great sprinters, like Italy’s Mario Cippolini, his role model) will require Bahati to retrain some of his naturally occurring fast-twitch muscle fibers into more energy-efficient slow-twitch fibers. To win, he’ll need a U.S. PostalÐ or Once-caliber team to support him. Still, Bahati scored two top-ten finishes in his first European stage race in Antwerp this fall, with no support from his national team comrades, who had fallen back. “It’s like you’re a musician playing the drums,” says Bahati. “If you keep getting to gigs and performing, eventually someone will notice.” —M. P. Tim Johnson [25]

[CYCLOCROSSER]

Middleton, Massachusetts

As if the sport weren’t brutal enough—cyclocross competitors slog modified road bikes over tarmac and dirt, dismounting at full tilt to carry their bikes over obstacles—American riders before 1999 were forced to start races at the back of the pack. But that year, at the World Cyclocross Championships in Poprad, Czech Republic, Johnson pedaled through blinding snow to finish third in the under-23 division, putting an American on the podium for the first time in cyclocross history. The bronze gave the Yanks some cred in the Eurocentric sport (“We’re not looked at as freaks anymore,” says Colorado’s Marc Gullickson, Johnson’s chief rival) and earned Johnson a spot on road-racing Team Saturn. “My goal is to get stronger using the road,” says Johnson, who won the 2000 U.S. National Championships, and who’s gunning for another cyclocross world medal this February in Monopoli, Italy—this time in the elite category. “Winning takes luck you can never count on, but a medal is a dream I can achieve.” —Alan Coté

Watermen

Saether in the Berkshire Hills, Massachusetts

Saether in the Berkshire Hills, Massachusetts Ludden in Glacier National Park, Montana

Ludden in Glacier National Park, Montana Maktima on the Pecos River, New Mexico

Maktima on the Pecos River, New Mexico

Mariann Saether [22]

[STEEPCREEKER]

Otta, Norway

This daughter of the Jotunheimen Mountains has a thing for waterfalls. In August, after warming up in 2000 and 2001 with a handful of 45-foot drops in Ecuador and Argentina, she became the first woman kayaker to run northern Norway’s Smaadoela Falls—a 54-foot plunge into a potentially lethal whirlpool. With just four years of paddling under her belt, the Dagger-sponsored Saether has already notched first descents in four countries, including a five-day source-to-sea paddle of her homeland’s Lomsdalen River and the remote Reykjafoss in Iceland. She also nailed the 2002 Norwegian Freestyle Championship title and, last May, wore the bronze at the Pre-Worlds in Austria.

“My ex-boyfriend was a kayaker,” says the five-foot-eight former synchronized swimmer. “As soon as I tried it, I couldn’t get enough.” Today, Saether is putting the gears to her testosterone-pumped costars in kayaking films like Teton Gravity Research’s Valhalla.

“She’ll step up and run gnarly drops, and we’re like, ‘Aw shit, now we gotta go,'” says Bozeman, MontanaÐbased pro paddler Ben Selznick, 25. “She’s one of the best female paddlers in the world.” Apparently that’s what happens when you spend more than 300 days per year in a boat. “Maybe I’m a little bit of a control freak,” says Saether. “I want to master everything about paddling.” —Mark Anders

Michael Phelps [17]

[SWIMMER]

Baltimore, Maryland

His dimensions aren’t freakishly impressive (six foot four, 187 pounds, 7 percent body fat, size 14 flippers), but world-record-destroying, ass-kicking swimmer Michael Phelps has something else going for him: the Equalizer. After this kid flip-turns from breaststroke to freestyle for the final leg of the 400 individual medley—a moment when even the strongest of swimmers pop up to chug some air—Phelps stays underwater. Last August, at the P66 Summer Nationals in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, he stayed under for an extra 12 meters and Man-from-Atlantised right past his main rival, Erik Vendt, surfacing in the lead and breaking a two-year-old world record. “Very few people are in good enough shape to do that,” says Bob Bowman, Phelps’s coach of six years. “Everybody went nuts.” Phelps, who also holds the world mark in the 200 butterfly, serves as the yang to Australian freestyler Ian Thorpe’s yin. Both are shooting for a gaudy number of golds at the 2004 Summer Olympics in Athens. The magic number is seven, which is how many American swimmer Mark Spitz won at Munich in 1972. —Eric Hagerman

Brad Ludden [21]

[RODEO KAYAKER]

Vail, Colorado

Though some of his pro-paddling peers are notorious self-promoters, spud-boat superstar Brad Ludden is cut from different neoprene cloth. Sure, he’s won his share of rodeos, including three golds at the Teva Mountain Games in his hometown of Vail, and yeah, you can catch him hucking his heart out in films like Nurpu and Valhalla. Then there are those 75-plus first descents of rivers like the Luapula, in central Africa, and the upper reaches of Indonesia’s Asahan. Yet Ludden, who next plans to paddle the upper Blue Nile in Ethiopia, stands apart for a different kind of achievement. In August 2001 he founded First Descents, a free, weeklong paddling camp based out of Vail that aims to build confidence in young cancer patients. “That’s where my heart is,” says Ludden. “It’s the one thing in my life that I know is good. I don’t question it.” Neither do we. —M.A.

Norman Maktima [22]

[ANGLER]

Glorieta, New Mexico

“When Norman stalks fish, it’s like watching a heron,” says Duane Hada, 40, who coached Maktima as a member of the U.S. Youth Fly Fishing Team back in 1998. “He’s got that predator in him.” That year the hip-wader crown prince, then 18, netted the highest score at the Youth World Flyfishing Championship in Wrexham, Wales. At 21, Maktima—whose father taught him to fish on New Mexico’s Pecos River at age seven—became the youngest American ever to compete in the World Flyfishing Championships, in Sweden. A member of the San Felipe Pueblo, Maktima hopes to develop sustainable fishery management programs on Indian reservations. Last spring he completed his bachelor of science at Washington State’s Whitman College with a double major in environmental studies and biology. His senior thesis: “Dietary Habits of Rainbow Trout in the Walla Walla River.” Says Maktima, “I’d go out there for a whole day and pretty much just fish.” He got an A. —S.H.

Ben Ainslie [25]

[SAILOR]

Falmouth, Cornwall, United Kingdom

At the 1996 Atlanta Olympics, Ainslie settled for silver in the Laser event after Brazilian Robert Scheidt, the eventual gold medalist, forced him into a false start in the last race, disqualifying him. Four years later, in Sydney, Ainslie returned the favor, boxing Scheidt in on the first upwind leg and then hanging on for the overall victory. Ainslie’s response to Scheidt’s subsequent griping? “What goes around comes around.” A few months later, the British phenom—whose father, Roddy, skippered a yacht in the first Whitbread Round the World race—signed on with the Seattle-based America’s Cup syndicate OneWorld Challenge. “I thought I would have the chance to be helming the boat,” he says, “but that never happened.” Quitting OneWorld, Ainslie bulked up 20 pounds, jumped into a Finn dinghy (bigger and more powerful than a Laser), and on his first try won this summer’s Gold Cup at the Finn-class world championships in Piraeus, Greece. After the 2004 Games in Athens, Ainslie expects he’ll give the America’s Cup another go—provided, that is, he can do a little steering. —R. B.

Skydiver

Nelson at the Skydive Chicago Skydiving Center, Ottawa, Illinois

Nelson at the Skydive Chicago Skydiving Center, Ottawa, Illinois

Matt Nelson [22]

[FREEFLYER]

Ottawa, Lllinois

If you think competitive skydiving involves little more than jumping and dropping, allow Matt Nelson to bring you up to speed. At the second U.S. Freeflying Nationals, held in October 2001 in Chicago, the third-generation parachutist risked multiple skull fractures in a terrifying blind maneuver that involved plunging to earth while whizzing around a pair of teammates back to back and headfirst for 45 seconds. “I like the stick-it-or-go-home-crying moves,” Nelson says. So did the judges: The home-brewed routine propelled him and his pals in Team Alchemy—Jon DeVore, 27, and Mike Swanson, 29—to a national championship in a brand of airborne gymnastics that’s the hottest thing to hit skydiving since the helmet cam. Talent seems to run in the family. “Nelson’s been in the sport for 18 years, and he’s only 22,” says Omar Alhegelan, 36, a member of Arizona Freeflight, a competing team. “Let’s just say Tiger Woods didn’t start playing golf when he was 16. It’s the same deal.” —Eric Hansen

Speed Skater

Ohno’s medal-winning 1,500-meter Olympic run

Ohno’s medal-winning 1,500-meter Olympic run

Apolo Anton Ohno [20]

[SPEEDSKATER]

Seattle, Washington

With his flowing mane and soul patch, his requisite unorthodox childhood—he was raised alone by his Japanese-American father, Yuki, from the age of one—and his uncanny feel for the ice, Apolo Anton Ohno seemed destined for stardom long before Salt Lake City. Still, no one could have scripted Ohno’s wild 2002 Olympic ride: He was leading the 1,000-meter race when another skater fell and triggered a NASCAR-style pileup on the last turn. After a frantic hands-and-knees scramble for the finish line, Ohno emerged with the silver—and a deep gash in his right leg. Four days later, he came back to win the 1,500 when South Korean star Kim Dong-Sung was disqualified for a blocking foul on the last lap. Ohno’s gracious words after both races endeared him to fans everywhere—except South Korea, where he remains a pariah. National outrage over the result climaxed during last summer’s World Cup soccer match between South Korea and the United States, when a South Korean player, celebrating a goal, mocked Ohno by pretending to speed skate on the field. “I had to look at it humorously,” Ohno says. “I was like, Maybe this guy wants lessons or something.”

Ohno and the rest of the American short-track team skipped the first stop on this season’s World Cup circuit last October in Chuncheon, South Korea. His diplomatic explanation: “The whole team is pretty behind, it being an Olympic year—we all took a little break.” Still, Ohno will be ready for this season’s world team championships in Sofia, Bulgaria, in March, and will “definitely” go for at least one more Olympics. “I’m only 20 years old,” he says. “I plan on a long career in this sport.” —Rob Buchanan

Visionaries

Gardner in Jackson, Wyoming

Gardner in Jackson, Wyoming Left to right: Harding, Van Tuyl, and Endrizzi at Jimmy Slinger Headquaters, San Diego

Left to right: Harding, Van Tuyl, and Endrizzi at Jimmy Slinger Headquaters, San DiegoWill Gardner [16]

[FILMMAKER]

Jackson, Wyoming

“Mom says it’s good for us to stay busy,” says Will Gardner. Chalk up another one to good parenting: While other Jackson teens kill time with their PlayStations, this aspiring Warren Miller already owns his own production company, School Bus Productions, and has two ski movies under his belt and a third coming out in a matter of weeks, as well as deals with corporate sponsors Cloudveil and Life-Link. La La Land, Gardner’s latest entry in the digital-video, adrenaline genre, is classic ski-porn: Nine eye-popping segments of young guns sticking massive aerials, rail slides, and powder rides, along with a few token blowouts—all set to a skittering rock-and-rap soundtrack. What’s next? “We would like to do some Matrix-type shots where the camera goes around the skier,” says Gardner. “But that, for us at least, is pretty far off.” If the reception for his last film, Mental Harmony, is any indicator—it filled the Jackson Hole Playhouse—Garder will get there sooner rather than later. “For being only 16, he’s pretty impressive,” says Teton Gravity Research cofounder Todd Jones. “The level of their riding has increased significantly, their filmwork and editing has increased significantly. I mean, they’re real.” —Christian DeBenedetti

Severn Cullis-Suzuki [23]

[ENVIRONMENTALIST]

Vancouver, British Columbia

At the age of nine, Severn Cullis-Suzuki launched the Environmental Children’s Organization—a kid-focused green group that organized beach cleanups. At 12, in a speech that brought the house down, she urged delegates at the 1992 Rio de Janiero Earth Summit to work on healing our ailing planet. A year later she published the book Tell The World and accepted the UN Environmental Program Global 500 Award for her precocious politicking. In high school, Cullis-Suzuki, daughter of renowned Canadian environmentalist David Suzuki, helped hammer out the UN Earth Charter with the likes of Mikhail Gorbachev and Jordan’s Princess Basma. “Sev’s not just a defender of life; she embraces life with boundless energy,” says writer and anthropologist Wade Davis, 48, a family friend and mentor. “Her idea of a fun thing to do is ride her bike across North America.”

These days the recent Yale graduate is promoting The Skyfish Project (), a group she cofounded last spring that is inviting people to sign a personal code of environmental ethics. In early 2003 she plans to trek the highlands of Nepal. Were it possible, she’d take her whole generation with her. “I worry that more and more kids my age are growing up without experiencing the outdoors, which means that fewer will care about the natural world,” Cullis-Suzuki says. “Get outside! Go be in nature! Then you’ll know why it’s important.” —B. B.

Ian Van Tuyl [23]

Elise Endrizzi [25]

Matt Harding [27]

[ENTREPRENEURES]

San Diego, California

OK, so one of them is over 25, but we’re bending the rules for this one because the young turks at Jimmy Slinger Skateboards are out to change the way the world thinks about commuting. “We’re dedicated longboarders,” says Matt Harding, an Orange County surfer who grew up rolling to the beach on five-foot-long skate decks. “It’s a great way to get around, and people are using them more as transportation, whether it’s going to the beach or six blocks to the supermarket.”

Frustrated with the shortboard-dominated industry, Harding and fellow thrash-culture entrepreneurs Elise Endrizzi and Ian Van Tuyl formed Jimmy Slinger in May 2000. (The name’s just a lark, says Harding: “There is no Jimmy Slinger.”) They cut their first flats with a jigsaw and shaped them by hand. Now the San Diego startup’s line ranges from 34-inch hybrids to its $165 signature product, the Big Duke, a five-foot-long maple glider strong enough to shoulder some serious beef. “We had a 300-pound guy buy one, and he just cruises on it,” says Endrizzi. Swamped with orders, the Slinger crew works late nights filling requests. “When we put in these long hours, I think about a company like Sector Nine,” says Van Tuyl, referring to the board maker that started in a La Jolla backyard and has since bloomed into a global powerhouse. “I’d love to do what they did, take an industry and make it into something.” —B. B.

Explorer

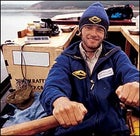

Cope takes a shift on the oars, Angara River, Siberia

Cope takes a shift on the oars, Angara River, Siberia

Tim Cope [24]

[EXPLORER]

Gippsland, Victoria, Australia

In the time it took to grow shoulder-length locks and a beard, Australian Tim Cope transformed himself from unknown university student to world-class adventurer. After training as a wilderness guide in Finland in 1998, Cope and his Aussie bud Chris Hatherly spent 14 months biking from Moscow to Beijing—a 6,200-mile slog. Along the way, they endured three grueling days man-hauling their bikes and gear 12 miles through six-foot snowdrifts in Russia. Six months later, Cope—who credits climber and author Joe Simpson for inspiring his unconventional approach to life—was back in Siberia, rowing a wooden boat with a team of four down the Yenisey River, bound for the Arctic Ocean. “He wants a challenge, but he’s not just into it for the feats of endurance,” says Colin Angus, 31, the Canadian expedition leader who invited Cope on the Yenisey trip. “He uses the hardship as a way to meet the local people.”

“I don’t like to suffer,” Cope says, “but when people see you putting yourself out there, they respond and let you in.” No doubt Cope will make a few new friends starting next summer on his 30-month circumnavigation of the Arctic Circle. This time, he plans to use a variety of conveyances: reindeer, kayaks, and skis. “The cold makes the reality of life as a struggle for survival more obvious,” Cope says of the northern climes. “You get the feeling of being in a landscape that’s totally undisturbed, like a real explorer.” —Brad Wieners

Endless Winter

December

Squaw Valley USA, California

SQUAW IS THE LEGENDARY SHRINE of extreme skiing, populated by serious skiers and snowboarders tackling serious lines. It’s the place where some of the country’s most talented freeskiers—new-schoolers like Shane McConkey and Jonny Moseley and pioneers like Scot Schmidt—hone their extreme skills before heading off in midwinter to take on bigger mountains around the world. SquawÕde;s 4,000 acres and prodigious drops, like the Palisades, will continue to draw the talent that made Squaw famous, but with plenty of cruising runs in Siberia Bowl and Shirley Lake, there’s something here for everybody.

COOL DIGS: The Resort at Squaw Creek (doubles, $150-$350; 800-403-4434, ) is a one-stop hot spot, with lodging, dining, spa, shopping, and direct lift access to the mountain.

MOUNTAIN STATS: summit, 8,900 feet; vertical drop, 2,850 feet; skiable acres, 4,000; annual snowfall, 450 inches

LIFT TICKET: $58 Contact: 800-545-4350,

Kicking Horse Mountain Resort, British Columbia

THE PURCELL MOUNTAINS of eastern British Columbia are where heli-skiing was born in the 1960s, and until the 2000-2001 season, people just flew over the high bowls and ridges of the front range. That’s when a major resort finally opened, promising more than 4,000 vertical feet and big-resort amenities to challenge Whistler Blackcomb as the king of western Canadian skiing. Kicking Horse lets a firm base develop until mid-December, but come for opening week to get first tracks on Blue Heaven, accessed this year by the new Stairway to Heaven quad. If the early-season snow is thin, you can always sign on for a day or two of heli-skiing with local operators based in nearby Golden (we recommend Purcell Helicopter Skiing, 877-435-4754, ).

COOL DIGS: Accommodations in Golden are of the motel-chain variety, so your best bet is to stay in the brand-new Whispering Pines town homes at the resort (rates start at around $106 per person, lift ticket included; 866-754-5425, ).

MOUNTAIN STATS: summit, 8,033 feet; vertical drop, 4,133 feet; skiable acres, 2,300; annual snowfall, 300 inches

LIFT TICKET: $32 (2001Ð2002 price) Contact: 866-754-5425,