“We’re putting too much into the ocean and taking too much out,” says Wallace J. Nichols, skipping the mind-numbing stats a guy with his credentials—he’s an Ocean Conservancy senior scientist and a top sea turtle expert—could recite in his sleep. “Putting too much in? Go a week without creating plastic waste. Taking too much out? Check out .” The site, started by Nichols in 2007, urges consumers to stop eating the country’s most popular seafood, which is typically caught using turtle- and dolphin-killing nets. It’s one of many issues Santa Cruz, California–based Nichols has tackled while juggling research (he was the first to discover that Pacific loggerheads migrate almost 7,500 miles to the coast of Japan) and working with more than a dozen conservation groups. This year, among other projects, he’ll help Mexican villagers develop profitable turtle-watching tours and lead the Ocean Conservancy’s first SEE Turtles trip, which puts travelers face to face with the creatures. “Sea turtles are sentinels for the ocean,” he

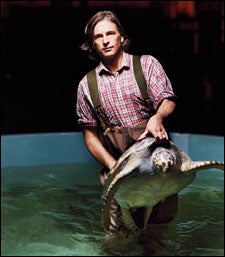

Wallace J. Nichols

Wallace J. Nichols photographed with Diego, a black turtle, at the California Academy of Sciences, in San Francisco

Wallace J. Nichols photographed with Diego, a black turtle, at the California Academy of Sciences, in San Franciscosays. “They’re my portal into everything.”

Edward Norton

Actor, 38

“I don’t believe in stepping out front on matters that you’re just getting educated on,” says Edward Norton. “I gravitate toward topics on which I have something to contribute.” For Norton, a lifelong environmentalist whose father, Edward Sr., was the senior adviser for the Nature Conservancy’s China program, that’s meant throwing his weight behind a litany of issues, like the greening of affordable housing. While growing up in Chesapeake, Maryland, Norton volunteered at the Enterprise Foundation, a nonprofit started by his grandfather, the philanthropist James Rouse, that provides housing for low-income communities. Norton, who sits on the board of trustees, convinced Enterprise to start the Green Communities Initiative, a $550 million commitment to make affordable housing more sustainable nationwide. In 2003, Enterprise partnered with the energy company BP Solar to launch its Solar Neighbors program, which donates a full solar setup to a low-income Los Angeles family for every solar system a celebrity buys.

At home, the Manhattan-based Norton is a founding board member of Friends of the High Line, an advocacy group working to establish a public park on an abandoned train line on the city’s West Side. “Creating a green space in Manhattan isn’t a high-crisis issue,” says Norton, who doesn’t own a car and takes public transportation. “But you have to tune in to what’s relevant in your community.” Next up: Hollywood. While filming The Incredible Hulk: Part 1 in Toronto this fall, Norton (who bulks up in a digitally engineered green suit for the role) attempted to reduce the film’s footprint by cutting back on paper waste, eliminating idling vehicles on set, and exploring the development of a film-production carbon calculator. “I wouldn’t say we’ve achieved any meaningful success yet,” he says. “But sometimes you just have to put one foot in front of the other and start.”

Heidi Cullen

Climatologist, 37

Heidi Cullen

Heidi Cullen photographed at Tishman Speyer Park, in Atlanta

Heidi Cullen photographed at Tishman Speyer Park, in AtlantaIn 2003, when Heidi Cullen started as the first-ever mainstream-media reporter to cover climate change, she didn’t set out to politicize the way the world views weather. She didn’t have time. The Weather Channel gave her 90 seconds a few times a week to try to make long-term climate issues relevant. For many viewers, and even a few meteorologists she worked with, that was 90 seconds too many. “They’d say, ‘We can barely get a weeklong forecast right, so how can you predict what will happen 50 years from now?'” says the plain-talking scientist, who has a Ph.D. from Columbia University in climatology and ocean-atmosphere dynamics. “But that’s bullshit! We know that there are nearly 6.7 billion people on the planet that spill out 7.2 gigatons of carbon dioxide. If we continue to spew at the same rate, the climate is going to get a hell of a lot warmer and a hell of a lot more expensive to deal with.” Meanwhile, the Weather Channel’s 87 million viewers started paying attention. In October 2006, the channel launched Cullen’s show Forecast Earth, the first weekly television program dedicated to climate change. In January, the show was expanded to an hour. Now that she’s getting some airtime, Cullen’s goal is pretty basic: “I’m reaching out to people who watch and say, ‘This is freaking me out; I don’t understand the weather anymore.'”

Eric Larsen

Polar Explorer, 36

Eric Larsen

Eric Larsen photographed in Minnesota at Lake Superior

Eric Larsen photographed in Minnesota at Lake Superior“I love winter,” explains explorer and global-warming advocate Eric Larsen when asked what a dog-musher with limited mountaineering experience is doing planning an Everest expedition. “I’m trying to tell the story of the last great frozen places on earth, and the reality is that those places are disappearing.” The other reality is that the polar-exploration race seems to have shifted focus—from who can go farthest or get there first to who can craft the most compelling podcasts about what we’ve got before it’s gone. In the battle for storyline, the Grand Marais, Minnesota–based Larsen, who has been to Canada’s Hudson Bay and to the North Pole, among other expeditions, has come up with a winner: His 2009 Save the Poles project () is a quixotic quest to reach the North and South poles and the summit of Everest (the “third pole”) within 365 days. He’s been planning the trip while touring the country giving climate-change lectures and working on a book about his 2006 summer expedition to the North Pole. “It was definitely an eye-opening experience,” says Larsen of that journey, during which he contended with thinning ice and a confused polar bear well outside its usual domain. “I became focused on being more responsible in my personal life.” On the Save the Poles trip, Larsen plans to post regular blog updates and collect scientific material for the National Snow and Ice Data Center for a documentary about his yearlong journey. “I’m an optimist,” he says. “People have an amazing ability to affect their environment for positive or negative. But we need to do things right now.”

Van Jones

Human Rights Activist, 39

Van Jones

Van Jones photographed at the People's Grocery Community Garden, in Oakland, California

Van Jones photographed at the People's Grocery Community Garden, in Oakland, California“We can no longer have a racially segregated, class-indifferent environmental movement,” says Jones, a Yale-educated lawyer who cofounded the Oakland, California–based Ella Baker Center for Human Rights. “We need ordinary working folks who aren’t worrying about how they’re going to put solar panels on their second home.” Jones thinks saving the environment isn’t possible without saving our inner cities, an issue he’s been striving to address for more than a decade. His approach? Help both simultaneously. In June 2007, the charismatic activist created Green for All, an initiative that trains inner-city youth in eco-friendly work. If we trade blue-collar jobs for green-collar ones, Jones says, we’ll keep kids out of prisons by teaching them skills—like installing solar panels on homes—that can’t be outsourced. Congress passed the initiative as the Green Jobs Act of 2007, which will authorize $125 million to train 35,000 people each year. “Right now, the icon of our environmental movement is someone wearing Birkenstocks, doing yoga, and eating tofu,” says Jones. “We need a new icon: the hard-hat-wearing, lunch-bucket-carrying, sleeves-rolled-up man or woman that’s fixing America.”

Chris Jordan

Photographer, 44

In 2003, Chris Jordan realized he was on to something after photographing a pile of trash that he found strangely alluring. “When I made a big print of that and put it on the wall of my studio,” the Seattle-based photographer says, “people would come over and look at it and they would start talking about consumerism.” Jordan’s garbage photo became the basis for a series called Intolerable Beauty and put him on the map as a commentator on our culture of disposability. “I started using beauty as a seduction,” he says of his photos, which feature stacks of oil drums, junked cars, or massive piles of bottles and cans. Before turning seriously to art, Jordan spent a decade as a corporate lawyer trapped in what he calls the “consumer trance.” “Whatever seemed cool, I would buy it,” he says. As Jordan began to take his photography more seriously, he says, “I wanted my work to be relevant, but not ugly.” His most recent series, Running the Numbers, includes “Cans Seurat,” which from afar looks like a copy of a famous Seurat painting but actually, upon closer inspection, depicts 106,000 individual aluminum cans—representing 30 seconds of American consumption, according to Jordan. Still, somewhere behind the message of wastefulness, there is a cautious optimism to his work. “I have tremendous fear and sadness about where we are right now,” says Jordan, whose prints have been seen everywhere from the Nobel Peace Center, in Oslo, to The Colbert Report, on Comedy Central. “But with something like a photograph, there’s a chance we might feel enough to care enough about it to change our behavior.”

Juan Pablo Orrego

Photographer, 44

Juan Pablo Orrego

Juan Pablo Orrego photographed at the Berkeley Pier, in California

Juan Pablo Orrego photographed at the Berkeley Pier, in CaliforniaJuan Pablo Orrego has a score to settle. During the nineties, the Santiago, Chile–based activist squared off with Endesa, a multi-billion-dollar Spanish energy company that proposed damming Chile’s pristine Bío-Bío river. For his efforts, Orrego won the prestigious Goldman Environmental Prize in 1997—and Endesa built two enormous dams on the Bío-Bío anyway. Now, as coordinator of the Chilean NGO Ecosistemas, Orrego is battling Endesa over the crown jewel of the adventure-sports world: Chilean Patagonia. Endesa Chile, a European-owned company, has partnered with the Chilean company Colbún and is proposing to clear the way for five dams on the Pascua and Baker rivers, free-flowing waterways that originate near two Patagonian icefields and run into the Pacific Ocean. The 106-mile Baker, known for glacier-fed turquoise water and rainbow trout that can exceed seven pounds, flows alongside the site of the proposed Patagonia National Park.

“They already destroyed the upper Bío-Bío, and now they want to degrade the most magnificent rivers in Patagonia,” says Orrego. This is a matchup that makes David and Goliath look like a fair fight. The dam project, which would cost an estimated $4 billion, is backed by one of Chile’s most powerful families, the Mattes, who are ranked 137th on Forbes‘s 2007 list of the world’s richest billionaires. Orrego, a former professional bass guitar player who studied with shamans in Mexico, coordinates the resistance from a three-room office in Santiago. But by amassing an international legal team and allying with organizations like the Natural Resources Defense Council, International Rivers, and Spanish Greenpeace, Orrego has mounted a formidable defense. “What happened on the Bío-Bío can never happen again,” he says. His solution: tapping local alternative energy like wind, solar, geothermal, and tidal power and ramping up adventure tourism. “When done right, tourism is the industry without chimneys, and it lasts forever,” says Orrego. “Unlike dams.”

Jeremy Jones

Big-Mountain Snowboarder, 32

Jeremy Jones

Jeremy Jones photographed in Truckee, California

Jeremy Jones photographed in Truckee, California“All skiers and boarders are polluters,” says Jeremy Jones, snowboarding pioneer and star of 12 Teton Gravity Research movies. “But we pollute a lot less than we did five years ago.” With his new Truckee, California–based nonprofit, Protect Our Winters (POW), Jones represents the ski-bum contingency in sounding the climate-change alarm. “A couple of years ago a friend suggested I start a climate-change foundation,” says Jones. “I thought, I don’t lead the perfect carbon-neutral life, so who am I to take the lead?” But after receiving his first few thousand dollars in grant money from his sponsor Rossignol, Jones officially launched POW last September. The organization is primarily educational, running no risk of pushing the limits of climate science—the home page, , offers tips on how skiers can reduce their carbon footprints (carpool to the mountain; walk and bike whenever possible). But in December, POW gave its first grant, a $4,000 donation to a solar-power program in a Wyoming school district, and will provide two more $25,000 grants this year. The grassroots approach is working—the 700-strong POW pulls in five new members per day, and, at press time, a European launch of the organization was slated for January. “Donations are coming from mountain-town locals,” says Jones, who lived out of his car at the beginning of his pro career. “Climate change is no longer just being talked about by Sierra Club members and hybrid owners. Everybody wants colder winters.”

Q’orianka Kilcher

Actress, 18

Q’orianka Kilcher

Q'orianka Kilcher photographed in Malibu, California

Q'orianka Kilcher photographed in Malibu, California“I started acting to give voice to the voiceless,” says the half-Peruvian, half-Swiss Q’orianka Kilcher, best known for playing Pocahontas opposite Colin Farrell in 2005’s The New World. At that film’s Peruvian premiere, she used the red carpet to draw attention to the plight of the forests of the Amazon basin. “People who read In Touch magazine might never know about these issues,” she says, “but it’s really those people you need to reach.” The Santa Monica, California–based Kilcher took a yearlong sabbatical from acting in 2006 and traveled back to the Peruvian Amazon to film indigenous leaders, who showed her the way oil companies have degraded and poisoned their rivers and forests. In 2007, she won a prestigious Brower Youth Award. In 2008, she’s planning a film project in an Alaskan wildlife refuge, and hopes to use her lead role in a biopic of Princess Kaiulani, the last princess of Hawaii, filming this spring, to draw attention to indigenous peoples. One last project she’d like to squeeze in: summiting Alaska’s Mount McKinley in honor of her grandfather—Ray “Pirate” Genet, a legendary Denali guide. “I want to climb it before it melts,” she says. She’s kidding, sort of.