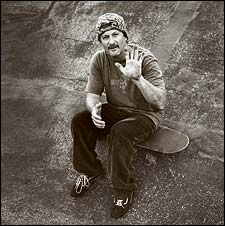

Stacy Peralta extends an arm toward the ghost of Pacific Ocean Park, the amusement complex CBS created on an old pier over the Santa Monica breakers in 1956. After the park was shuttered, in 1967, the area around the corroding mega-pier quickly mutated into an autonomous zone ruled by a ferocious crew of Venice and Santa Monica surfers, and the scene came to be known by the nickname for their run-down seaside neighborhood: Dogtown. The crew’s inner sanctum was a surf break called the Cove, protected on three sides from wave-killing winds by a bristling grove of 20-foot-tall pilings. Throwing punches, jetsam, and stolen carburetors at interlopers who tried to poach their sacred right-hand wave, the crew created a kind of Thunderdome-by-the-Sea.

stacy peralta, riding giants, documentary

Peralta ripping in back of Mar Vista Elementary School—the first playground he was officially kicked out of as a young skate rat.

Peralta ripping in back of Mar Vista Elementary School—the first playground he was officially kicked out of as a young skate rat.stacy peralta, riding giants, documentary

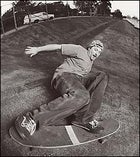

“Riding Giants”: Laird Hamilton’s hail mary at Peahi, Hawaii.

“Riding Giants”: Laird Hamilton’s hail mary at Peahi, Hawaii.stacy peralta, riding giants, documentary

“Dogtown” : Jay Adams riding the concrete surf.

“Dogtown” : Jay Adams riding the concrete surf.stacy peralta, riding giants, documentary

Stacey Peralta at Mar Vista Elementary School, Los Angeles, California

Stacey Peralta at Mar Vista Elementary School, Los Angeles, California

The pilings and the Cove are long gone—the ruins of the park were finally demolished in 1975—and the only thing remaining is a sign on the beach warning swimmers about underwater debris. “There’s not even any debris left,” says Peralta. “I checked it out.” He doesn’t sound wistful—he’s just setting the record straight.

With black wraparound shades and a blond goatee flecked with gray, Peralta, 46, is the picture of the aging surfer. You could easily mistake him for one of those glaze-eyed union guys working the boom on a movie set, pulling together enough cash to disappear to Baja or Indonesia for a few months at a time.

But you’d be wrong. Stacy Peralta is, in fact, one of Hollywood’s hottest new filmmakers. Three years ago, he reached down into Davy Jones’s locker and memorialized on screen the whole decaying eminence of Pacific Ocean Park and, more famously, the Dogtown skate scene it spawned—the Big Bang of modern skateboarding. Peralta’s 2001 documentary Dogtown and Z-Boys pulled off the trick of making everyone who saw it wish they’d been there—while garnering the approval of those who actually were. It also earned Peralta best-director and audience-favorite awards at that year’s Sundance Film Festival.

Now Peralta has followed up with a second boarding epic: Riding Giants, a documentary on the birth and explosion of big-wave surfing that he put together in ten months for just over $2 million. The film became his second triumph at Sundance, opening the festival in January and earning a standing ovation from an overflow crowd. Sony Pictures Classics snapped up the distribution rights, and the film rolls out nationwide July 9.

When the lights go down, audiences will be hit with a blast of apocalyptic horn-and-organ music played over slo-mo aerial shots of man-killing ocean avalanches. This segues into the sound of turntables scratching over metal guitar riffs as tiny surfers plummet down waves at monster breaks like Maverick’s and Jaws. Jumping from slo-mo to fast-forward to reverse, splicing razor-sharp 35mm film with grainy 16mm footage, Peralta unrolls an almost forensic examination of the stormy November 1957 day when Greg “Da Bull” Noll, Pat Curren, and a handful of other Southern California haole imports paddled out into 20-foot waves at Waimea Bay, on Oahu’s North Shore, and cemented big-wave riding as a sport unto itself. And that’s just the first ten minutes.

Having established himself as the Ken Burns of rad, Peralta now finds his edgy authenticity in high demand. Hollywood is thirsty for the box-office juice that recent surprise surf hits like the babes-on-boards feature Blue Crush and the documentary Step into Liquid delivered, and screenplays have been pouring in. Meanwhile, this spring, Columbia Pictures will begin shooting a feature based on the Dogtown days, and Peralta has been talking with Sean Penn (who narrated Dogtown) about directing the Oscar winner in an adaptation of In Search of Captain Zero, Allan Weisbecker’s 2001 surf-trek memoir. There’s also a third picture in the lineup, based on Noll and the North Shore pioneers.

But as Peralta stands here on the Santa Monica sand, all that seems far off. What’s currently showing on the busy screening room inside Peralta’s skull is the terror and wonder of his first Pacific Ocean Park experience, in 1970. Peralta, a platinum-haired 13-year-old, and two equally frightened friends had snuck through a passageway under the park’s corroding hulk, watching in awe as the Cove crew rode their secret wave.

“What are you little punks doing here?”

Looming over the three eighth-graders was Craig Praycon, a Cove legend, wearing a Russian Cossack hat and military-surplus overcoat.

“If I ever see you here again,” Praycon told them, “I’ll kill you and bury you in the sand!”

“We left skid marks,” Peralta laughs now.

But Peralta went back, alone. He endured hazing and intimidation, working his way up the pecking order until the local Zephyr Surf Shop, which sponsored both the surfers and skate rats, offered him a spot on its junior surfing team. “As a kid, you need to find out who you are,” Peralta says. “That’s how you find out.”

STACY PERALTA WAS BORN on October 15, 1957—three weeks before Greg Noll’s legendary ride at Waimea—and grew up a couple of miles from the beach in a nondescript subdivision in Mar Vista, California. His mother was the personnel manager for an oil firm, his father a movie-studio accountant. “They’d let me skip classes if the waves were really good,” he says. When the surf was bad, he would skateboard, pretending his neighbors’ fence was a double overhead at Oahu’s Sunset Beach.

Peralta and his more flamboyant Zephyr teammates, Tony Alva and Jay Adams, took their skateboards into Dogtown’s drainage ditches, asphalt schoolyards, and empty backyard pools. By the late seventies, their Zephyr skate team, the Z-Boys, dominated national competitions, hopping mainstream America’s back fence and dropping their extreme selves into its sporting consciousness. Peralta was considered the circuit’s best all-around rider.

In 1978, as Alva and Adams descended into rock-star lifestyles befitting their sudden fame, Peralta dipped a toe into commercializing his talent, appearing in a Pepsi ad and on Charlie’s Angels. But then, at 21, he left the limelight to join aerospace engineer George Powell’s year-and-a-half-old Santa Barbara–based skateboard company, which was rechristened Powell-Peralta. He assembled a team of younger phenoms, the Bones Brigade, tapping a gawky 13-year-old named Tony Hawk for the squad, alongside riders Lance Mountain, Steve Caballero, and Mike McGill.

In 1983, Peralta shot and directed The Bones Brigade Video Show, a skateboard stunt tape that Powell-Peralta shipped out alongside its new line of decks and wheels. Skaters across the country began huddling around stores’ TV screens, mesmerized by Hawk & Co. in action.

“The shops started calling,” Peralta remembers, “saying, ‘If there’s one thing you do this year, make another one of those tapes.’ ” He directed Future Primitive in 1985 and, in 1987, The Search for Animal Chin, still regarded as the genre’s lone classic. Tony Hawk remembers how Peralta, legendary for keeping his cool, almost lost it during the making of Animal Chin. “He got frustrated because he had to deal with prima donnas,” he says. “Us. He basically left for the day to regroup, and showed up the next without passing blame.”

By the end of the eighties, Powell-Peralta was a 150-employee company pulling in $30 million a year. Peralta had recently married Joni Caldwell, whom he’d met in postproduction on the fourth Bones Brigade video, Ban This, and they had a son on the way. Peralta was 33, a subculture mogul. And he was over it.

“I’d spent years hanging out with 15- and 16-year-old guys,” he says, “climbing fences with them, risking arrest, living on fast food, and lying under tables to get good shots.” He wanted to make films—real films. So, in January 1991, he told Powell he was getting out.

Through his connections from the artfully gritty Bones Brigade premiere parties, Peralta landed a few jobs a year directing low-budget commercials and cable-TV pilots. He’d wake up at 4:30 a.m. to work on screenplays for a few hours before heading off to direct, say, a Nickelodeon project about exotic animals.

He sent off his first screenplay, The Medium of Exchange, a black comedy based on the idea of people as currency. After it was rejected for the third time, he started on another. And another, and another. “The feedback I was getting,” he says, “was basically, ‘Not only are you not going anywhere with this, but it really sucks.’ “

Eight years after walking away from skateboarding, Peralta found himself working in a concrete bunker off the Hollywood Freeway, producing a documentary on showbiz highlights of the seventies for New York’s Museum of Television & Radio. There was a family of rats living and—worse—dying in the drop ceiling over his edit bay. “Something went wrong,” he remembers telling himself. “I followed my heart. This wasn’t how it was supposed to go for me.”

Things got worse. In the fall of 1999, as his marriage was heading for divorce, Peralta got a call from a producer who wanted to buy the rights to his piece of the Dogtown story. Spurred by skateboarding’s late-nineties reemergence, thanks to the X Games and Tony Hawk’s signature video games, the producer had discovered that all roads to the sport’s roots led through Peralta.

“I thought, This is just what I need right now,” Peralta says. “The part of my life I was proudest of, made into some schlock high school comedy.”

PERALTA WENT TO THE MOUNTAIN—literally. At the top of Zuma Ridge Trail, 1,400 feet above Malibu, he looked down at the ocean and made a decision: Let them make their phony feature. He’d make his own documentary, and get it right.

Peralta started making calls to skate buddies he hadn’t talked to for years, and was astonished at how happy people were to help him: Jay Wilson, the head of marketing for the skate-shoe company Vans, staked $400,000 on him and, later, $200,000 more. Peralta began rummaging through attics in search of forgotten Dogtown footage, and hired private detectives to track down alumni. As audiences discovered, he possessed a sly genius for getting boarding’s toughest alpha males to reveal their fragile inner rippers. In Dogtown, for example, Jay Adams, the baddest of the legendarily bad Z-Boys, regretfully reflects on the way his life veered into a succession of legal problems and jail time.

The combination of stunts, attitude, and emotional truths struck a chord. Jimmy Page, the former lead guitarist for Led Zeppelin, saw Peralta’s seven-minute trailer and agreed to license “Hots on for Nowhere” and “Achilles’ Last Stand” at bargain-basement prices. Jimi Hendrix’s estate followed suit. Sean Penn, who invented the onscreen surf dude in his role as Spicoli in Fast Times at Ridgemont High, narrated for free. Peralta was aiming for cable release, but a camerawoman convinced him to submit Dogtown to Sundance.

With Riding Giants, Peralta proves that Dogtown was not just a fluke. Once again, the poetry of the board-riding rush is intercut with deeper flashes. Greg Noll tenderly anthropomorphizes Waimea Bay as a lover who’s thrown him over for younger guys, then expresses astonishment at the wet stuff in his eyes. Even the stoic Laird Hamilton talks about being picked on as a haole kid in his Hawaiian grade school.

“I’ve interviewed Laird dozens of times,” says Sam George, editor of Surfer and Peralta’s co-writer on Riding Giants. “I have to admit, what Stacy was able to pull out of him really surprised me.”

The same thing impressed Hollywood. Producers called again, and this time they weren’t in search of schlock. At press time, in mid-March, Lords of Dogtown was set to start production in early April, with Catherine Hardwicke (Thirteen) directing and Heath Ledger as one of the lead actors. The screenplay is Peralta’s.

“The thing about Stacy,” says the film’s executive producer, John Linson, “is that he does the work—the work that everybody else doesn’t do.”

IF ALL THE ACCLAIM is going to his head, Peralta isn’t showing it: He maintains a low-key, posse-free modus operandi. During a five-hour afternoon interview that takes us up and down the beach and back to the site of the old Zephyr Surf Shop, he never once pulls out a cell phone. He drives a Toyota Sequoia, lives modestly in Santa Monica with his girlfriend of three years, Fox Searchlight Pictures executive Stephanie Allen, and shares custody of his 13-year-old son, Austin. And he hasn’t forgotten his decade out in the cold.

“Yeah, it’s nice,” he says over lunch at the swanky beachside hotel Shutters, staring at the blown-out afternoon surf. “You go to Sundance for ten days, you’re pampered, and you get to feel good about yourself. Then it’s back to the hellfire of Hollywood for the rest of the year.”

The hellfire is more than the sum of his past struggles and the travails of industry sleaze. It’s also about leaving documentaries behind and taking on features. “I could stick with what I’m doing, strip-mine it, and make a lot of money,” he says, “but it’s time to move on to other things.”

Of course, before anyone’s going to give Peralta $40 million for his own projects, he’s going to have to prove two things: one, that he can cross over from documentaries, a leap few directors have made; and two, that he can transcend the long, inglorious tradition of bad surf films: North Shore, Point Break, and—the horror—In God’s Hands. But the one man who’s come closest to getting the surf genre right thinks he can.

“Stacy is the best documentarian out there today,” says John Milius, who directed the 1978 surf bomb turned DVD hit Big Wednesday and wrote film’s most memorable depiction of the surfer’s obsessive mind-set, Robert Duvall’s “Charlie don’t surf” scene in Apocalypse Now. “It doesn’t matter whether it’s about surfing or skateboarding,” Milius continues, “or that those things are trendy right now. It’s about kids having a moment of grace in the sun, rock stars trespassing in an empty pool with the cops on the way—demigods for an afternoon. And there’s a sadness, because that moment goes away. And everybody can relate.”

“With Stacy’s strengths, he’s got a better chance at doing something great than people who came from rock videos or commercials,” Milius argues, alluding to such directing talents as Adaptation‘s Spike Jonze (who grew up with the Bones Brigade videos) and Fight Club‘s David Fincher, both of whom have done just fine.

Maybe. If Peralta succeeds, it will be because of his willingness to dive beneath the Hollywood surface, to sift through the debris on the seafloor. But this much is certain: Once again, Stacy Peralta is about to find out who he is.