“BOOM!” BELLOWS LAIRD HAMILTON as a 20-foot wave explodes off the sea cliffs on Maui’s northern coast, spraying foam into the rosy dawn sky. The greatest big-wave surfer on the planet, and perhaps the greatest of all time, Hamilton is shirtless at the helm of his camo-green jet boat. A dozen surfboards are piled in the bow, bouncing with the chop, and mile-long wave bands are rolling through the blue Pacific.

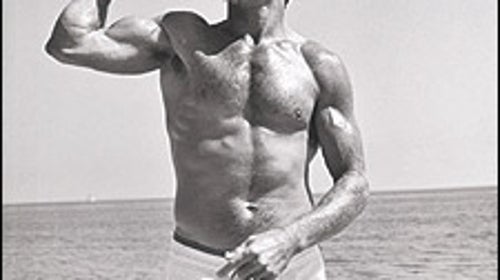

Laird Hamilton

Laird Hamilton

Laird HamiltonLaird Hamilton

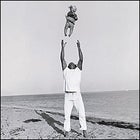

Laird Hamilton, with daughter Reece, in Malibu

Laird Hamilton, with daughter Reece, in MalibuLaird Hamilton

Laird Hamilton

Laird Hamilton

“Boom!” he yells again, pointing to a craggy lava outcropping 100 yards off the bow. “Isn’t that great! We call it Dynamite Rock.” His white-toothed grin turns crazy with exhilaration as he recounts a time several years ago when he convinced filmmaker Sonny Miller to shoot him as he scrambled onto Dynamite Rock, hid under a boulder, and let waves detonate all around him. It was all just for fun—part of Hamilton’s “Hey, watch this” approach to serious risk—until the pull of a receding wave began sucking him off the rocks. “I got caught and drilled,” Hamilton recalls. “It wasn’t as dramatic as it looked, but it was still pretty exciting.”

Now the 40-year-old Hamilton steers the boat straight for another Maui landmark: Jaws, the infamous deep-water break that routinely unleashes 40- and 50-foot monsters. Long considered unsurfable, Jaws was conquered in 1993 after Hamilton and some buddies decided to use jet skis to tow surfers into the waves—a move that marked the start of Hamilton’s transformation into who he is now: the reigning big dog of surfing. With athlete-model wife Gabrielle Reece, a 14-month-old daughter, and the kind of physique American boys dream of seeing in the mirror, Hamilton boasts the surf world’s most outsized personality and most recognizable face. He trains harder than everyone else, takes wilder risks, stars in more surf movies, and—with savvy, self-made ambition—brings more innovation and energy to the sport.

But all of this is ancient history—that is, pre-2004. This year, Hamilton elevated himself into a new realm of athletic stardom. His prime-time attention came packaged in a July 60 Minutes appearance—via waterproof live radio-feed headset straight from a west-Maui wave—and through silver-screen exposure in Riding Giants. Hollywood chiseled Hamilton onto the Mount Rushmore of big-wave riding, alongside the great Hawaiian legends and 1960s big-wave pioneer Greg Noll.

Which explains why this bronzed, six-foot-three, 220-pound specimen of physical perfection is having so much fun in his jet boat. Even as he’s out here goofing off, carpenters are framing his new 3,500-square-foot house in Haiku, just up the road from Jaws; his new production company, BamMan Productions, won the Best Film award at Park City’s X-Dance Action Sports Festival earlier this year for a TV pilot called The Ride, starring Laird; and he’s still right here on Maui, still in the water, still refusing to compromise the life he loves. After so many big breaks, why should he? There’s little arguing that 2004 has been the Year of Laird.

HAMILTON WAS BORN TO SURF. His family moved from San Francisco to Oahu’s North Shore when he was an infant, in 1964. It was the sport’s modern heyday, when world-class Hawaii breaks like Sunset Beach and Pipeline played host to greats like Jock Sutherland, Gerry Lopez, and Hamilton’s stepfather, Billy Hamilton, who taught Laird to surf when he was two. Hamilton also had the looks: At 17, he was discovered by a photographer for L’Uomo Vogue (Italian Men’s Vogue) on a Kauai beach; the images landed him a 1983 photo shoot with Brooke Shields.

He could easily have trodden the well-worn path from clothing endorsements to dominance on surfing’s World Championship Tour, the sport’s most prized competitive venue. But organized contests were never going to cut it for Hamilton. “How do you judge art?” he scoffs. He’d seen the pain suffered by his stepfather at the whims of judges. “It was devastating,” Hamilton says. “Financially, trying to feed a family, but also not getting due respect because you won’t dance the way they want you to dance. I would snap if I was letting someone other than the audience determine my fate. How does a musician judge his thing? By how many people love his music.”

Rejecting the contest circuit meant that Hamilton had to devise an alternate route to fame. This he did brilliantly, starting in the early 1990s with Maui’s legendary Strapt crew. A gang of eight friends that included fellow all-star Rush Randle (page 96), the Strapt boys blew minds by launching 30-foot jumps on sailboards, then mating the boards to paragliders to experiment with some of the earliest kiteboards. In late 1992, Darrick Doerner, Buzzy Kerbox, and Hamilton started using Kerbox’s Zodiac—and, later, jet skis—to tow one another into waves too big to catch under paddle power alone. Hamilton quickly learned not just to survive 80-foot waves but to carve gorgeous arcs across walls of water that could literally sink ships—putting high drama back into a sport long preoccupied with small-wave tricks.

Soon, Hamilton was receiving the recognition he craved. In 1994 he appeared on both ESPN (with his first wife, Brazilian bodyboarder Maria Hamilton) and the cover of this magazine. That same year, he landed a lucrative sponsorship from the French beachwear company Oxbow. Then, in 1995, he took an unexpected detour. He left his wife and baby daughter and moved in with professional volleyball player Gabrielle Reece in Los Angeles. (They married in 1997.) Reece, who’d parlayed her bump-set-spike into international celebrity, “knew all about being in a sport where you had to create something out of nothing,” as she says. She soon hooked Hamilton up with her own talent manager, Jane Kachmer. “When I met Laird,” Reece says, “he needed some professional organization. Janie really had to get creative. Being female is an easier card to play. But we understood image.”

In short order, Hamilton’s career began looking a lot more like Reece’s: In 1996, People magazine named him one of the 50 Most Beautiful People in the World, and he replaced Reece as correspondent for the syndicated cable series The Extremists. In 2000, he hosted the Fox Sports Network’s Planet Extreme Championships. His death-defying drop into Tahiti’s Teahupoo break—at the time, considered the most dangerous wave ever ridden—was named ESPN’s Action Sports & Music Awards’ Feat of 2001. That year, Hamilton and Reece had what she calls a “hiccup,” and she filed divorce papers, but they reconciled a few months later and Hamilton continued his steady rise to fame, surfing as Pierce Brosnan’s James Bond stunt double in 2002’s Die Another Day.

Things took a meteoric turn in 2003, when—thanks to the box-office success of Blue Crush—surfing was suddenly Hollywood-hot for the first time since the 1966 cult classic Endless Summer. Hamilton scored major screen time in Artisan Entertainment’s Step Into Liquid, the 2003 surf documentary that grossed upwards of $3.5 million. Riding Giants, which debuted at Sundance in January and was released nationally in June, was an even bigger coup for Hamilton, who landed both a leading role and production credits—and was heralded onscreen by director Stacy Peralta as the greatest monster-wave rider of all time.

These days, as if to prove it all again, Hamilton is training like a man who knows that his body is his future. A standard day, when he’s not surfing, involves hill climbing with 50 pounds strapped to his mountain bike, two hours of circuit training, three miles of surfboard paddling, and a personal favorite: harnessing himself to a log and dragging it for miles down the beach. His workout partners include John McEnroe and NHL All-Star Chris Chelios, of the Detroit Red Wings, who says he’s “never worked out with anybody in quite that shape. He’s a natural phenomenon.”

Despite his über-fitness, Hamilton still refuses to compete, even as the big-wave gold rush unfolds on his home break of Jaws. On April 16, 2004, the Billabong XXL Global Big Wave Awards, surfing’s most prominent contest, handed 43-year-old former Strapt crew member Pete Cabrinha a check for $70,000 for riding a Jaws 70-footer that made it into the Guinness Book of World Records. Hamilton, meanwhile, has never entered photos of his giant rides in the Billabong competition—a decision that is as much about principle as it is marketing savvy.

Hamilton’s main sponsor, Oxbow, is reluctant for Billabong to profit from Hamilton’s image. Arenaplex’s November 2003 release Billabong Odyssey, for example, documented a team of expert big-wave riders on a quest for the world’s biggest surf, and when they came to Maui to get the Jaws story, Hamilton declined to participate. As a result, Billabong Odyssey had to tell the entire story of tow-in surfing without any mention or footage of its foremost pioneer, Laird Hamilton.

By staying above the fray, surfing only for himself, he has become a lone, untouchable Neptune, reigning over a swelling pantheon of competing demigods. “You’ll never hear from me, ‘I rode the biggest wave,’ ” says Hamilton. “Because you hurt yourself by saying, ‘This is it.’ Like a benchmark. Then people want to step over that. For me, it’s less about the one big wave than about your performances. It’s about your body of work. It’s art.”

ON A CLEAR AND WINDY DAY, at his usual hangout, Anthony’s Coffee Co., in the small north-coast Maui town of Paia, Hamilton holds court like a mafia don in an Italian trattoria. They sell his DVDs at the register, encourage admirers to nod but not approach, and stock everything for Hamilton’s Atkins-on-steroids breakfast regimen: New York steak, slabs of salmon, and poached eggs.

Hamilton knows perfectly well, of course, that he’s at the peak of his physical powers, and that now is the time to capitalize. That’s why, even as he sips coffee in this sleepy beach town, the wheels of his entrepreneurial machine are churning, thanks largely to BamMan Productions. Maximizing the next phase of Hamilton’s career, BamMan will allow him to serve as the star, producer, and owner of every second of Laird water-action footage from now on. And, with any luck, it will provide him a viable business when his best surfing years are past.

First on the agenda is to turn BamMan’s The Ride into an extreme-sports reality-TV series, and Hamilton insists that a Disney Imax big-wave movie is on the horizon. And always brewing in the back of his mind are ideas for further big-wave innovations—hydrofoil boats pulled by kites, speed-sailing, underwater bodysurfing, paddle-surfing—which, with any luck, will keep him in the spotlight and provide cutting-edge, exclusive footage. “We have the best cameraman in the world,” he says, cutting into his salmon and nodding to two middle-aged realtors at the next table. “We have the best helicopter pilot, the best riders, and it’s all right here, whatever they need. It could be 60 for 60: a 60-foot screen with a 60-foot wave and a six-foot guy. Awesome.”

It is awesome, which might explain why one of the realtors, looking from Hamilton’s plate to Hamilton’s Marvel Comics physique and then back to his plate, asks the waitress what every man in the room is no doubt thinking: “Can I please have the Laird?”