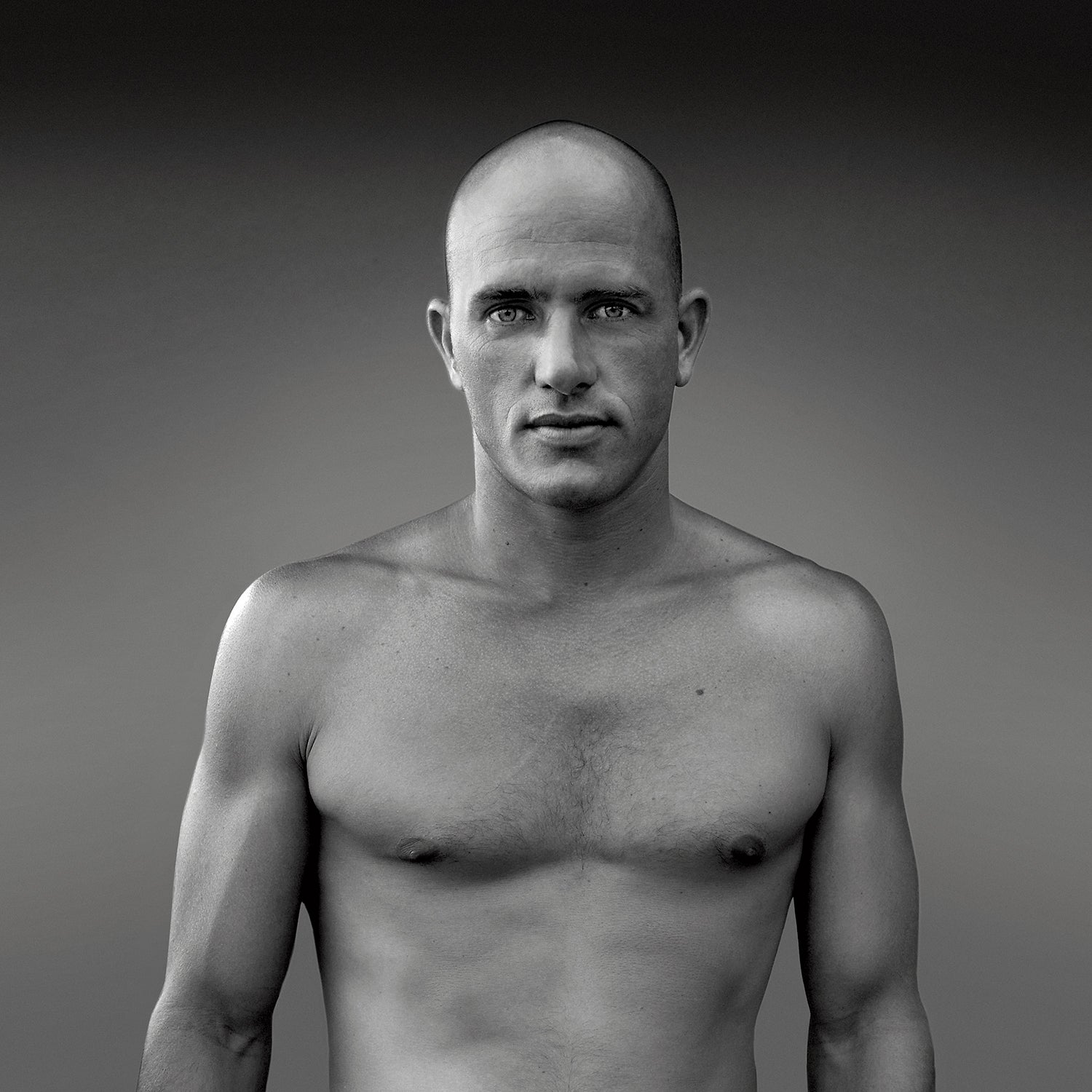

Go ahead—take a deep breath. If the recent electoral madness and economic meltdown have left your nerves frayed, join the club. But the new year is dawning and the world has not ended. Sure, you're probably still too scared to take a close look at your stock portfolio, and we'll see how that upheaval on Pennsylvania Avenue turns out. But don't laugh when we say that this next year should be your best yet. Because in chaotic times, there's one thing you can control: yourself. With this in mind, we've devised a seven-step plan to help you beat stress, get fit, be smarter, and eat right. Our key consultant is a guy who knows a thing or two about excelling in all sorts of conditions: , 36, surfing's world champion for a remarkable ninth time. Still holding your breath? Well, let it out. Your transformation starts now.

1. Just Chill

Here's the ironic thing about stress: The human body has evolved to cope with it too effectively. When you suffer under a crappy boss—a stressful situation, sure, but hardly life-threatening—your body responds as if you're being chased by a predator. Stress hormones like cortisol, epinephrine, and norepinephrine spike, causing your attention to narrow and your body's inflammatory reactions to kick into high gear. This would help you avoid infection if, say, your boss bit you, but when continuously activated, inflammatory reactions can wreak havoc on your health, leading to increased risk of heart disease, stroke, depression, and diabetes. Chronic stress can even shrink your hippocampus, a part of the brain that supports learning and memory. In short: You need to calm down. Here are six easy ways to do so. —By Catherine Price

Rage Against the Machine

Yoga has its time and place, but if you're feeling overwhelmed, consider something more actively cathartic, like boxing. New research shows that heart-rate-elevating exercise promotes neurogenesis—the growth of new nerve cells—creating an effect similar to that of antidepressant drugs. While the verdict is still out on how high-intensity and low-intensity exercises differ regarding neuro-genesis, your goal should be to significantly elevate your heart rate. Studies suggest that if you box, sprint, or play soccer, you'll promote mood-improving brain-cell growth. Ditto if you go for a long run (that might get you high, too—see page 51). “Everyone knows how important exercise is to your heart,” says , a professor of psychiatry at Yale University. “What's becoming more clear is that it's just as important for your brain.”

Laugh Out Loud

One of the myriad effects of chronic stress is that it lowers the potency of your body's virus- and cancer-fighting cells. But in 1997, Mary Bennett, director of the and a researcher of humor's impact on immune function, found an easy way to mitigate these effects: Laugh. When Bennett drew blood from a group of volunteers before and after they watched a stand-up-comedy video, she discovered that natural killer cells functioned better in the people who'd laughed aloud. And a recent study at California's showed that merely anticipating a humorous experience led to dramatic decreases in cortisol and epinephrine. So next time you're tearing out your hair in front of the computer late at night, do yourself a favor and spend 20 minutes on .

Dare to Downshift

Want to enjoy the relaxing benefits of meditation without joining a monastery? No problem. A 2007 study published in the  found that giving students just five days of instruction in something called integrative body-mind training (IBMT) lowered their levels of anxiety and stress-related cortisol. IBMT is similar to many traditional meditation practices in that it focuses on relaxation, but it doesn't emphasize controlling your thoughts—the hard part. Here's the point: Meditation calms you down, even in small doses. The easiest way to start is to sign up for a course at a center such as Marin County, California-based . Don't have that much free time? Download a Jack Kornfield for beginners.

Take a Hike

A little stress in the airport security line is worth it: Science shows that active travel is one of the best ways to hit your body's natural refresh button. Whenever you expose yourself to a new experience, your brain releases noradrenaline and dopamine, which make you feel alert and enjoy the moment at hand. (Acute stress, meanwhile, narrows your focus so that you can barely enjoy a slice of pizza at lunch.) By “active travel,” however, we don't mean actively sitting on a beach—trying to force yourself to relax can have the exact opposite effect. “In that situation, we remove all stimulation and try to empty our mind,” says University of Colorado psychology professor . Like intense meditation, this takes a lot of work. Going to the Bahamas? Then explore them. Go fishing. Get off your beach blanket and visit a new town. Take surfing lessons. When you return, you'll be renewed and able to fend off stress with the memory of that shoulder-high wave you rode all the way into shore.

Use Your Hands

We're a nation of depressives. According to Randolph-Macon College behavioral neuroscientist , author of  (2008), we're ten times more likely than our grandparents to suffer from the blues. The clinical blues, that is—not the my-girlfriend-dumped-me sort. Why? We've abandoned physical interactions with our environment. “A lot of our mental illnesses are about the perception that we have no control,” says Lambert. She proposes that, thanks to our affinity for computers and drive-throughs, we don't engage the brain's “effort-driven rewards circuit” enough. Our ancestors made plans—”build shelter; plant potato; kill elk”—and executed them with well-evolved hands. It's called controlling your enviÂronment. When we do this, our brains reward us with dopamine. But these days we've stopped using our hands for much beyond punching buttons. So curing your mood may mean putting down your BlackBerry and pulling on some work gloves. A few suggestions: Grow a tomato plant. Be your own bike mechanic. Catch a fish. Clean it and eat it. Learn guitar. Call next in pickup basketball. Just don't lose—if you don't execute your plan correctly, well, you don't get the dopamine.

My Story:Â Thanks for Nothing

Last year, while suffering from midwinter malaise, I did something rash: I signed up for a happiness course in Berkeley, California, called “Awakening Joy.” It was founded in Buddhism but also incorporated elements of the emerging field of positive psychology. Some parts, like a 200-person sing-along to “Amazing Grace,” were brutal. But I did find a surprisingly effective way to reduce stress: gratitude exercises. University of California Davis professor of psychology , author of the book (2007), hypothesizes that expressing gratitude causes us to release pleasure-inducing hormones, like dopamine. But I wasn’t concerned with the biochemical rationale. Once a week, I wrote a list of things that made me grateful. It sounds cheesy, but it worked. Put the name of a good friend on paper and all of a sudden life doesn’t seem so daunting.

2. Play The Fields

To improve in a sport, you need to commit to it, right? Sure. But as most top athletes can attest, cross-training is essential. Stick to one game and you'll let key muscle groups fall by the wayside while risking burnout. Mix up your training and you'll keep your body balanced and your mind fresh. Exhibit A: , 27-year-old Olympic mountain-bike racer and former competitive kayaker and skier. Last July, Craig defended two titles at the U.S. mountain-bike nationals. His secret: a six-day-a-week training program that includes lots of time off the saddle. We asked Craig how his various sports benefit one another, then fact-checked his answers with (see footnotes), a leading exercise researcher at the Mayo Clinic. —By Matthew Fishbane

“I used to have lower-back pain. In 1998, I learned how to paddle, and I haven't had a back problem in a bike race since (1). When I'm home, in Bend, Oregon, I get out a few times a week for a paddle on the Deschutes River. I'll go for a bike ride in the morning, take a nap, then paddle in the afternoon (2). Someone told me I would have ridden better at the Beijing Olympics if I hadn't been dicking around kayaking [Craig finished 29th in a field of 50] (3). But I stick to the ideology that variety is good (4).

“In winter, I ski every day (5). You can't mountain-bike much, so you're training on a road bike, and you lose the central-nervous-system stimulation that you get from picking a line through a tree run (6). Carving a turn on skis with your torso vertical is exactly how you ride a mountain bike.

“I used to compete as a whitewater kayaker, and I was a ski racer in high school: nordic, alpine, GS, and freestyle. I don't do that anymore—I've got enough competition in my life (7). I ski and paddle to get away.”

Footnotes: The Expert Weighs In

- Kayaking is a natural way to train your core and upper body. Reduced lower-back pain is consistent with this.

- Remember that biking is this guy's job—we're not talking about an average person doing this to stay fit.

- To attribute one outcome in a single event to somebody's training program over a number of years is a little nutty.

- There is no one right method. Craig found a way to keep himself psychologically fresh, and that's great.

- You want to be active every day. If Craig keeps his aerobic power up, that will help keep his quads strong.

- This is a reasonable way of saying that, like mountain biking, skiing tests your balance and forces you to move in a coordinated way.

- Very wise. Being able to ration your competitive energy for the most important events is key.

Take Action: Vary Your Routine

Since you don’t have Craig’s luxury of biking and kayaking up to six hours a day, here are some simple, workable guidelines to cross-training from Holden Comeau, a triathlon coach with Philadelphia-based and Multi-sport Centers.

- Define the time you have—it’s easy to get overwhelmed if you make an unrealistic schedule. If you can work out for one hour, four times per week, that’s fine, as long as you’re consistent.

- If you’re a competitive athlete, 90 percent of your in-season training should be for your sport. Out of season, 25 percent should be in-sport. The rest of the time you should be cross-training.Â

- The specific sports don’t really matter; you’re just trying to become proficient with new movements.

- That said, there are some sports that work well together. If you’re a cyclist, run, swim, and, most important, hike. Cyclists don’t move laterally or up and down enough; hiking is great for that.

- In fact, hiking is great cross-training for any sport—surfing, skiing, you name it. The key with cross-training is to keep the intensity low; hiking builds aerobic strength at low intensity.

3. Loosen Up

For years, I thought if I set foot on a field without stretching first, I'd risk injury-induced benchwarming. This rule was reinforced by many a baseball coach, not to mention my own body type, which is about as pliant as cold concrete. I was tight, therefore I stretched. But in the past few years, many exercise scientists have sworn off static stretching (e.g. the hands-on-ankle quad tug), citing new studies that show it doesn't prevent injury or decrease post-exercise soreness and that it can decrease muscle power. dedicated an entire newsletter to debunking stretching's benefits; I just finished arguing with a University of Minnesota kinesiologist who spoke of stretching the way I'd speak about castor oil. But the thing is, stretching makes me feel good. And yoga and Pilates are basically advanced forms of stretching, right? What gives? I asked Andy Pruitt, founder of the , who lectures frequently on the myths of stretching, to cut through the fog. Here are his new rules of getting loose. —By Abe Streep

Get the Facts

There is no convincing evidence supporting the notion that static stretching prevents injury. But it may make you feel good. That's fine. Just warm up first.

Never Stretch Cold

Ever. The purpose of stretching is to lengthen tendons at the end of a muscle. Stretch cold and your muscle won't go to full length; you won't access the tendons. Always warm up with some light cardio.

It Shouldn't Hurt

If it does, you might be doing damage to your muscles or tendons. When you heal, you'll build up scar tissue, decreasing range of motion. Never do ballistic stretches—the bounce-to-touch-your-toes kind. If you bounce far enough, you can hurt yourself.

Know Your Range

Range of motion, that is. If you're a jogger, you probably don't need to stretch, because you have the range you need. But if you're playing soccer, a slide tackle might knock you into an awkward position, like a half-split. You want to make sure you can reach that extended range; stretching is one way to do this.

Go Dynamic

Another smart way to improve range of motion is with dynamic stretching, which allows you to lengthen your tendons while warming up with sport-specific movements. Examples include butt kicks, lunges, and karaokes. But don't start doing this until you get some basic instruction.

Get a Stretching Rx

If you think you have a limited range of motion from a past injury, talk to a physical therapist or sports physician. One thing they might suggest: PNF (proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation) tretches,which are often done with a partner. With this kind of stretching, the muscle contracts and then relaxes, allowing you to really access the tendon.

Be Realistic

Like me, you probably have about ten hours a week for sports. It's a question of priorities: If I have the range I need to cycle, am I going to spend one hour stretching? No. I'll be riding.

My Story: Hands on a Hard Body

Why one Olympian needs two professional stretchers. —By Dara Torres

You need to feel loose in the pool, and my body gets tight from strength training. I first tried resistance stretching in 2000. I dove into the pool and felt like Gumby. Now I have two trainers stretch me three times a week for recovery. It gets the tension out and makes it easier for me to have a good workout the next day. I’m resisting against a force, so I build muscle. When I was young, we’d do group stretches before getting in the pool. But what do you get out of trying to put your head down to your knee? For more information on resistance stretching, visit .

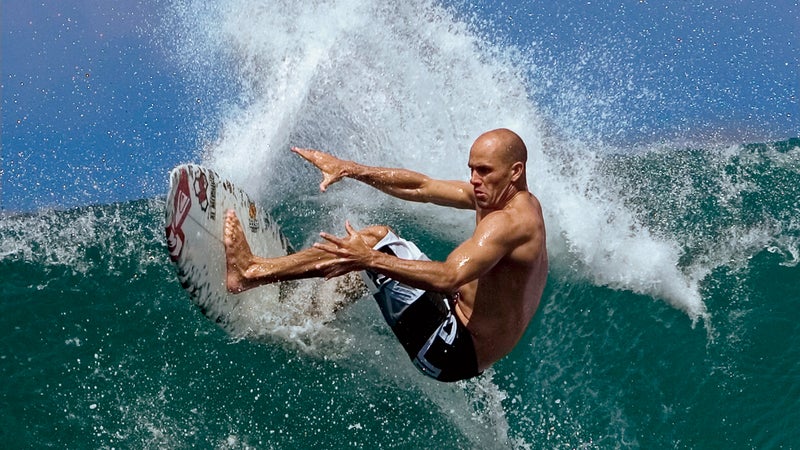

4. Win

It's not just about the basic act of surfing or boxing or whatever you do—you have to be confident to go out there and apply what you know. If you really understand a surf break, you know that most of the good waves break at point A; but over at point B there are waves that people don't realize can get you a good score. That's knowing the environment. I also really tune my equipment to where I'm surfing—switching boards and fins. Then you have your competitor. What's his strength? His weakness? He might have something going on in his life and maybe his confidence is wavering. Everyone has a chink in their armor, and you can learn to expose it. —As told to Michael Roberts

When you're not worried about the outcome, that's when you can discover things about yourself. You trust your gut and act on instinct.

Life changes. You can set out for a goal, and it won't happen. For me, it seems to work to just feel it as I go along. A lot of surfers think I'm trying to !@#$ with their heads when I say I'm not competing in a contest or on the tour. But I'm honest. I had every intention of not surfing on tour this year. And yet, here I am.

I've had times in my career where I'm just the utmost competitor: This is what I want; I want to win a world title. But saying that is putting yourself in a vise grip. Just talking about it puts me in a tense place. At this point, it's a loose thing for me. If I never win another world title, that's fine. If I do, great. That's not being ambiguous, it's: I'm gonna roll with it.

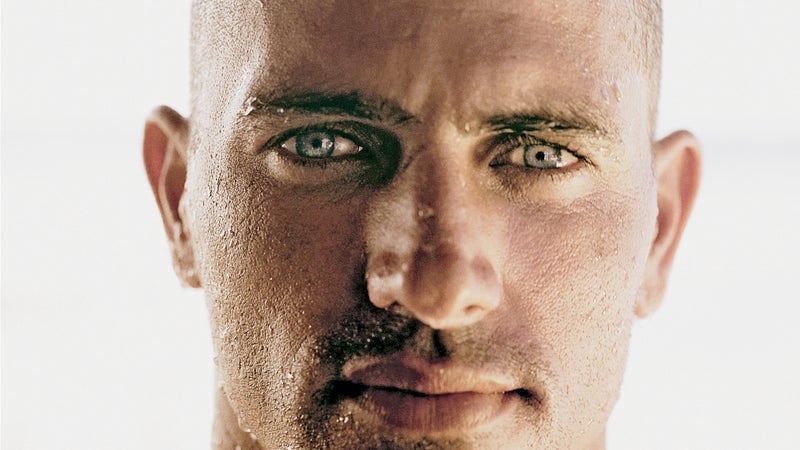

Kelly Slater On…

…Stress: “I'm a lot calmer than I used to be. I'm not as emotional. At the same time, I think I'm more connected to what I'm feeling. I try to observe what's going on around me, read the signs, and get the message. Life really is that simple most of the time.”

…°ä°ů´Ç˛ő˛ő-°Ő°ů˛ąľ±˛Ôľ±˛Ô˛µ:Ěý“I've learned a lot about technique and biomechanics from golf, and it's improved my power and efficiency in surfing. It helped me envision what i'm doing in a turn: standing in a neutral spot, then directing weight and gravity downward toward a plane. Competitively, golf has taught me that I can always turn things around. You can have the worst round ever, then suddenly make a hole in one.”

…ł§łŮ°ů±đłŮł¦łóľ±˛Ô˛µ:Ěý“We don't all need to be able to bend over and put our face on our feet. But you need to open up all your circulation and let blood get into blocked areas. Stretching also can make you aware of little injuries so you don't make them worse.”

…Desire: “I've heard people say that motivation is temporary and inspiration is permanent. There are days when I don't want to compete. I can't imagine competing right now, I put every bit of mental and emotional energy into this year. But I'm trying to have an inspired career, to live an inspired life.”

…Natural High: “There are all these chemicals your body releases. And when they're released in the right way, they can be stronger than any drug, with no bad side effects. Some days it happens, some days it doesn't. That's part of the beauty of it.”

…±·łÜłŮ°ůľ±łŮľ±´Ç˛Ô:Ěý“I have a basic rule of thumb with food: If I can't pronounce any ingredients—if there's any propyl-anything, or whatever—I won't eat it or put it on my body. When I travel, I carry some drink mixes and some raw-food bars in my bag.”

5. Catch A Buzz

For years, scientists maintained that exercise-induced endorphin highs were the stuff of myth. We're happy to report that they were dead wrong. —By Seth Fletcher

As marathoner Deena Kastor crossed the finish line at the 2004 Olympics in Athens, , she felt as if she could have run another few miles at the same pace. When Ryan Hall shattered the U.S. half-marathon record in 2007, he had an almost out-of-body experience, watching himself from above as he crossed the finish line. Even I, a half-assed jogger, occasionally experience a soothing calm during my lung-searing runs through the diesel-particulate fog near the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway.

All these sensations are different forms of runner's high, a phenomenon that endurance athletes have celebrated for decades but that, until recently, was as scientifically proven as Sasquatch. That's because there wasn't a way to observe the effect of endorphins—the body's self-produced opium—on the parts of the brain associated with exhilaration and euphoria. While plenty of studies found endorphins in the bloodstreams of people who'd just finished exercising, scientists debated whether or not those endorphins actually pass through the blood-brain barrier. Some thought the high was a myth.

But then a study published last year by researchers at the , Germany, gave ample evidence that runner's high is very much real. Neurologist Henning Boecker gathered ten runners, injected them with radioactive (but safe) tracers, then took a PET scan—a noninvasive snapshot—of their brains. On another day, Boecker's team took scans immediately after the runners comÂpleted a vigorous two-hour workout. Result: The tracers showed endorphins busily binding to receptors in the limbic and prefrontal portions of the brain—the areas responsible for feelings of ecstasy and joy. “We'd suspected that the release of endorphins must come from the brain,” says Boecker. “But nobody was ever able to show that until now.” (Prior to Boecker's PET scans, the only way to disprove the skeptics would have been to subject runners to a spinal tap not an easy study to recruit for.)

To a lot of runners and coaches, this was a case of science catching up with common knowledge. “It would be more surprising if they found nothing,” says Terrence Mahon, Hall's coach. “Any runner could tell you runner's high exists,” adds obsessive ultramarathoner , who recently ran for 48 hours straight on a treadmill. “When I'm able to push through the pain and not black out, I arrive at a different place.” [Editor's note: Not recommended.]

But Boecker's research goes beyond just vindicating those who swear by an athletic high. The fact that endorphins can give you a lift means that running—or cycling, or swimming, or any endurance sport—has the potential to treat depression, addiction, and pain, though more research is required. Once laughed at, runner's high could, before too long, become a staple in your doctor's Rx closet.

My Story: The Addict

What a really, really serious endorphin trip feels like. —By

For me it happens at about five or six hours. Up to that point it can be misery. But after mile 100, one minute you feel like you’re going to die, and with literally the next foot strike you feel like My God, I’m unstoppable. It’s like a self-induced Alice in Wonderland trip. Your hearing becomes more acute, and there’s an element of ego suppression. I once saw these rodents on the side of the road—possums, squirrels. This was during a 262-mile run in California, on the second night without sleep. The full moon came out, and these things morphed into Maurice Sendak monsters, howling and scratching into the moon. Later, my crew told me that there were no squirrels. There was just a guardrail.

Take Action:Â Tie One On

It feels sooo good. Trust us.

- Build a base first. If you're a newbie, jog for 30 minutes three times a week. If your muscles and bones are sound, your runs should start to feel good in three to four weeks.

- Everyone's endorphins kick in at different points—it's all about intensity in regard to your personal limits. Figure out a tough one-mile pace for yourself, and try to run at 80 to 85 percent of that speed for the longest distance you're comfortable, whether it's two miles or ten. Just don't try to sprint to a runner's high—intervals place such a huge demand on the body that you'll never have a chance to enjoy the endorphins.

- Train in the best outdoor setting you can find. “I don't know whether it connects with serotonin levels, or endorphins, or dopamine,” says Mahon, who coaches distance runners among the peaks of Mammoth Lakes, California. “But from an anecdotal standpoint, people are drawn to the outdoors because it makes their bodies feel good.”

6. Clear Your Head

Brain training is suddenly big business. But can you get smarter without geriatric video games or wildly expensive lab tests? As our Lab Rat learned, yes. —By Nick Heil

The mental calisthenics were pretty simple at first: Could I pick up an envelope off the floor? Did I know where I was? Then came the stumper: What day was it? “Wednesday wait a minute.” I glanced around the room for clues. Nothing. “It's Tuesday. No, Monday!” I blurted to , a psychologist who works at (CFIT), a brain-fitness facility in a leafy section of Santa Barbara, California. Kydland nodded and, wearing a serious expression, jotted something in her notebook.

CFIT is a new kind of mental-health outfit. Unlike the exploding number of commercial enterprises that purport to sharpen the mind using various electronic games and gizmos, CFIT addresses the whole picture: physical fitness, diet, mental activities, personal relationships, and medical history. “The idea here is to provide a thorough baseline assessment, then set you up on a program that will optimize your lifestyle to promote cognitive health,” says , CFIT's founder and a professor of neuroscience research at the University of California at Santa Barbara. In other words, CFIT is an everyman's brain gym: You pay an annual membership fee of about $4,000 and make twice-weekly visits to the place, Ă la Equinox.

Brain fitness has become big business over the past few years. Cerebral-exercise computer games from companies like Ěý˛ą˛Ô»ĺĚý generated $80 million in 2007, up from $2 million just three years earlier. An increasing number of high-end labs, such as Los Angeles based , help wealthy clients tweak attention-honing brain waves using EEGs and other state-of-the-art technology. CFIT, which is scheduled to be fully open for business by late 2008, offers something entirely different: an accessible, one-stop mind shop that promises to transcend the realm of the wonky and geriatric. For now, half of CFIT's pilot group consists of retirees with looming cognitive trouble the most ready and willing clients of the brain-training world but Kosik's vision is far bigger.

“I can see this sort of facility all over the country, for all kinds of people,” he says. (There's talk of opening a second CFIT facility in San Diego, with more on the horizon.) “The time to focus on brain health is when there is no disease at all.”

Until about 15 years ago, many experts believed the brain was hardwired, and that once mental deterioration set in, it was irreversible. But recent neuroscience research has convinced the scientific community that the brain is malleable into old age. This principle, called neuroplasticity, has neurologists racing to tweak the mind in order to improve sports and job performance and even stave off or reverse problems like AlzÂheimer's and Parkinson's. CFIT aims to prevent these illnesses, but also to teach people how to maintain their intelligence and mindfulness over the long term. And that proÂcess begins with the rest of the body. “People forget that the brain is an organ, like the heart and lungs,” Kosik says, “and that it benefits from exercise and sound nutrition.”

My first step was to come clean on how often I floss (only in that pre-dental-exam panic), whether I do drugs (uh cough, cough no), and how much red wine and chocolate I consume (plenty). Once the staff reviewed my general health, it was time for a little mind fitness. The exercises involving a stationary machine called the , a cross between an elliptical trainer and a stationary bike, and a widescreen TV set up with Nintendo's Wii were pretty basic at first. I experienced minor guilt pangs when, during a round of Wii boxing, I knocked out CFIT's petite director, Hether Briggs (well, her avatar, anyway).

I got my comeuppance during the neuropsychological evaluation. I aced a few of the initial tests, then struggled to remember what day of the week it was. I could repeat from memory a string of eight numbers in reverse, but for some strange reason I messed up while attempting the same exercise with just four numbers. At the end of our hourlong session, Kydland asked me if I could recall the questions she'd asked when I first entered the room (Do I wear glasses or use a hearing aid? How old am I?). I drew a blank. And then I felt a sudden chill. Was this a warning sign of bigger problems?

Before I mustered the nerve to ask this question, CFIT set me up with some mental exercises on a brain-training computer program called MindFit that involved various memory and hand-eye-coordination games. At first, it was about as challenging as desktop solitaire, but it got progressively harder, until I was floundering again. Clearly, I could use some more brain push-ups.

The next day I sat down with the CFIT team to review my performance and discuss a long-term DIY program. This is the most innovative and impressive aspect of CFIT: They put all the components of mental fitness together in a practical, manageable training program. In lieu of cool-but-mostly-useless brain scans that might show my frontal lobe lighting up like a Christmas tree (or not), I got smart advice that I could take home and apply immediately.

To wit: My physical fitness is fine; keep it up, Kosik told me. He offered nutrition suggestions, like adopting the olive-oil-and-fruit-rich Mediterranean diet, which, according to a 2008 study in the , promotes a 13 percent reduction in the occurrence of Parkinson's and Alzheimer's. Kosik also advocated a few supplements, like calcium, high-quality fish oil, and folate (a B vitamin that may prevent Alzheimer's). My team prescribed three 20-minute CogniFit sessions a week; though, to be honest, I'm more likely to commit my time to other equally effective brain-benders, like the Sunday crossword puzzle, Sudoku, learning guitar, or tackling another language anything, basically, that presents fresh challenges. “The better you get at a given activity,” said Kosik, “the less brain you use.”

One of the most compelling things I came away with is also the simplest: the vital importance of friendships. “A healthy and active social network is probably one of the best predictors of long-term mental health,” Kosik said.

“So I should keep playing soccer and going on ski trips with friends?”

“Absolutely,” he said.

Before I left, I had to ask Kydland about my quirky performance during the neuropsych tests. Was this, as I feared, a sign that I'm on the road to senility? “Don't worry,” she said reassuringly. “You scored completely within the normal range. You just weren't paying attention.”

Take Action: Sharpen Up

Think you don’t need to work your noggin? Try this simple test: Have a friend read two random four-digit sequences to you (for instance, 5-3-8-9 and 2-5-3-8). As soon as they finish, repeat the numbers out loud, but in reverse order (9-8-3-5 and 8-3-5-2). Next, try it with two six-digit sequences, then two eight-digit sequences. If you failed to nail it, your short-term memory could use work. Try any (or all) of the following brain-building tools—which also promote long-term mental health—20 minutes a day, three times a week.

- . Their MindFit DVDs are loaded with brain-benders such as the Stroop Test, which trains reaction time and memory. The program customizes difficulty levels according to each user’s ability and has been shown to improve everything from general health to driving.Â

- . These online entertainment-oriented games improve attention, language, and memory. Try “Heraldry,” which requires you to memorize various coats of arms.Â

- . This game for the pocket-size Nintendo DS features numerous brain-building challenges, from simple math problems to mega-popular games like Sudoku.Â

- Six-string guitar. Buy a beater on eBay and commit yourself to practicing three times a week. And play scales, not just the three chords you need to hack through “FreeFallin’.” You’ll improve your memory, keep your mind in top shape—and impress at the next cookout. —N.H.

Take Action:Â Reprogram Your System

Know that feeling when you want to keel over at mile five on your run? That's your brain playing mother hen. Sports scientists are realizing that everything from how fast you can run a 10K to how long you can bike at 20 mph is determined by the brain's understanding of the body's limits a protective mechanism known as “anticipatory regulation.”

“Job number one for your brain during exercise is to prevent you from working yourself to death,” says Ross Tucker, an exercise physiologist and consultant to the . This subconscious safety net is usually more conservative than it needs to be, unless you're an elite athlete. And research suggests that amateurs can boost their performance with workouts that safely recalibrate the brain's protective mechanism. Here's how.

- Wear a stopwatch or heart-rate monitor and warm up with ten minutes of easy swimming, jogging, or pedaling. Increase your effort to the fastest speed you think you can sustain for 20 minutes. But don't look at your watch hold your pace until you think you're near exhaustion. Stop and cool down.

- Jot down your average pace (for example, 7:30 mile for a run) and the amount of time you held that pace (don't feel bad when it's not even close to 20 minutes). Repeat the workout once a week and try to sustain the same pace for a slightly longer duration each time. Again, don't look at the clock push yourself by feel. Expect some improvement in your second try at the workout not because you're more fit, but because your brain is comfortable letting you work harder.

- In each subsequent workout, you should be able to go farther, thanks to improving fitness and a slightly less conservative brain. —Matt Fitzgerald

7. Fill 'Er Up

In 2005, endurance mountain biker Josh Tostado's nutrition plan consisted of lots of mac 'n' cheese and healthy servings of Coors. Back then, the six-foot, 160-pound Tostado was a small-time Colorado legend, having won the Montezuma's Revenge 24-hour race twice. But he was still working at a bar, so he gave up drinking and overhauled his diet. Three years later, the 32-year-old has a sponsorship with , and this past October he dominated the 24 Hours of Moab race. Here's what his day in food looks like. —As told to Devon O'Neil

I stopped buying anything you can't harvest or kill. I consume about 5,000 calories a day, and I'd say more than half of that is fruits, vegetables, and fatty nuts like walnuts and almonds. I eat most of my vegetables raw, because you can lose nutrients when you cook them.

Breakfast:Â I'll fry two eggs and eat them on a whole-grain bagel with a slice of ham.

Lunch:Â I usually eat two big turkey sandwiches on whole-grain bread with Swiss cheese, tomato, and mixed greens. I'll have some fruit or pasta on the side to stock up on good carbs.

Snacks: I eat six or seven clementines—or three or four oranges—every day. They're full of vitamin C and have high water content to keep me hydrated, and I love the taste of citrus. I'll also snack on walnuts and almonds throughout the day.

Dinner: I'll eat a piece of organic pork, fish, beef, chicken, or turkey, grilled with salt and pepper on it; a plain, baked sweet potato; and a salad that weighs about a pound and includes things like red pepper, carrots, radishes, avocado, and walnuts. Dessert is a cup and a half of plain berries—blueberries, blackberries, raspberries, and strawberries.

Fluids:Â I drink coffee in the morning but otherwise mainly water, because everything else has too much sugar in it.

Take Action: Eat This Way

For most of us, matching Tostado’s menu would result in a larger belt size. But his supersize diet follows smart principles that can benefit any active individual. Here’s how to apply them to your life.

-  Drink less If you have two six-pack nights a week, that’s approximately 1,800 excess calories with little to no nutritional value. Besides, people who regularly consume more than five drinks at once are at a higher risk of gastritis, hypertension, and heart attack. Moderation is key: One or two drinks (ideally red wine) each night is fine.

- Eat fresh Tostado’s “harvest and kill” philosophy sounds a lot like Michael Pollan’s. That’s a good thing. Don’t grow or hunt? Just stick to the periphery of your grocery store, where you’ll find all the essential fruit, vegetables, meat, and dairy you need.Â

- Spices, not sauces Using only salt and pepper to season your food is a great strategy. Many of our staple sauces are calorie-laden and unnecessary. For example, mayonnaise contains 11 grams of fat per tablespoon. If you need more than just salt and pepper, consider making a savory balsamic vinaigrette with olive oil, parsley, garlic, basil, and thyme.

- Snack on fruit Tostado surpasses the recommended five daily servings of fruit and vegetables, but most of us don’t come close. His citrus mania is great, but what’s important is that he’s found a fruit he can stick to—one that’s readily available, fresh in winter, and affordable. Find yours.Â

- Actually, a little fire is fine Cooking can improve veggies’ flavor. It’s better to enjoy cooked vegetables than to tolerate only a fewrawones. —Walter F. DeNino

Walter F. DeNino is the founder and president of , an online coaching and sports-nutrition service.