I’ve always been a little leery of mindfulness. Not the general concept, but the broader industry that seems to have spawned innumerable charlatans hawking everything from meditation apps, to glitzy yoga retreats, to self-help literature that mostly reminds you of stuff you already know. It sometimes feels like mindfulness is just about repackaging the obvious. On the other hand, just because something is glaringly self-evident doesn’t mean it’s always easy to remember. As George Orwell : “To see what is in front of one’s nose requires a constant struggle.”

Everyone knows that part of the quote, but the succeeding lines are less frequently cited: “One thing that helps toward it is to keep a diary, or, at any rate, to keep some kind of record of one’s opinions about important events. Otherwise, when some particularly absurd belief is exploded by events, one may simply forget that one ever held it. ” Orwell was referring primarily to the political realm, as he believed that people were less likely to engage in self-delusion when it came to their private lives. I’m not sure that that is true. But, either way, the notion of holding yourself accountable by regularly giving your thoughts a tangible reality on the page seems like an eminently sensible idea.

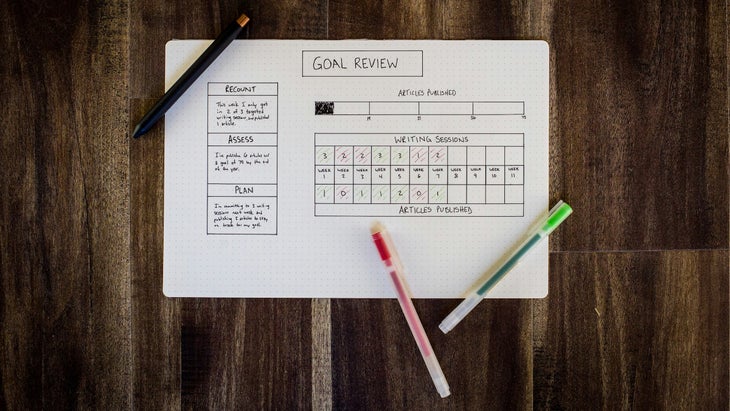

That’s the basic premise behind the method, a minimalist approach to journaling that touts itself as “a mindfulness practice designed as a productivity system.” Founded by digital designer Ryder Carroll in 2013, Bullet Journaling–or “BuJo” as it is known among acolytes—is essentially a glorified version of the to-do list, but with an additional nudge towards introspection. Practitioners—of which there are over one million, worldwide—are encouraged to record daily and monthly logs using a nifty notation system that distinguishes between tasks, events, and notes. The idea is not only to try and stay on top of your various obligations, but to continuously assess their relative urgency and importance. If you keep putting off a particular task, the thinking goes, you should probably ask yourself whether it’s really worth your time. In mindfulness lingo, this is called marrying your “what” with your “why.”

As a chronically distracted person, I have always wondered whether the key to a more productive and fulfilled existence was about finding a way to impose some kind of structure on my life. (Ideally, without becoming a Scientologist or joining the military.) One appealing aspect of BuJo-ing is that it doesn’t cost anything. Although the website sells everything from Bullet Journal courses to stationery to Carroll’s internationally best-selling book, anyone can try the method. All you need is a notebook and a pen.

Or, you can do what I did and purchase the “official” Bullet Journal—a customized model from the German stationery company Leuchtturm—for $30. (���ϳԹ���, in an instance of media-industry largesse, allowed me to expense this.) I also decided to log all my entries using a fancy fountain pen that someone gifted me years ago and had been languishing in my desk. Why not set myself up for success?

Following the instructional videos on the Bullet Journal website, I began by creating a “Future Log”: two notebook pages dedicated to mapping out the next six months of my life. I wrote down everything from the aspirationally optimistic (January: “Ask boss for a raise”) to the mundane, but necessary (March: “Book annual physical”), to pre-scheduled trips (February 17 to 24: “Ski week in Maine”). If any event triggered a specific emotional response in the moment that could be distilled into bite-sized notation, I recorded that, too. (“Hope I’m still too young for a colonoscopy.”) Next, I created a log for the current month. Although Carroll stresses that there is no one right way to setting up your Bullet Journal, the basic format for the monthly log is to dedicate one page to a calendar-style overview, and one page to a bullet-point summary of things you hope to get done in the next 30 days.

The most substantial part of Bullet Journaling is the daily log, in which you take some time every morning to outline tasks and then proceed to check in throughout the day, either to cross items off your list or to “rapid log” your thoughts. Any tasks left undone can be “migrated” (to use the BuJo term) to the following day, or crossed off because, on further reflection, it turns out they weren’t that important to begin with. Easy enough, in theory. Although I was able to be disciplined about taking five minutes to check in at the start and end of every day, I often struggled to use my journal consistently in the interim. More than anything, this was a matter of practicality; I spend half my workweek sitting in front of a laptop, where journaling can be a useful form of procrastination. But the rest of the time I work in arboriculture—“in the field” as it were—where busting out a six-by-eight-inch leather-bound notebook and fountain pen felt weirdly cumbersome the few times I tried it.

As a chronically distracted person, I have always wondered whether the key to a more productive and fulfilled existence was about finding a way to impose some kind of structure on my life.

Having said that, if the principal objective of becoming a BuJo disciple was to make myself slightly more organized and intentional with my time, I think the experiment was a success. As an organizational system, the Bullet Journal method was a vast improvement on my previous approach, which was to just try and remember shit. This will sound painfully obvious to all the people who already do it, but taking a few minutes to force myself to compose a daily task list had a dramatic impact on my ability to get stuff done. The effect was less pronounced when it came to big, externally imposed tasks like work deadlines or signing up for health insurance—i.e. the things that you’re going to do anyway—and more noticeable when it came to getting the ball rolling on zany side projects, or maintaining personal relationships. In other words, the kind of thing that you are always thinking that you should do, but that no one is going to insist that you must do.

This, at least for me, is the real value of Bullet Journaling. It’s easy to be seduced by the bombastic promise of the enterprise—the notion that it’s possible to subject every aspect of your life to a kind of internal audit to see how it contributes, or doesn’t, to your personal flourishing. (There’s a “What” and “Why” Venn diagram on the inside cover of my official edition BuJo.) Rather than forcing a grand realignment of my personal priorities, I found that the practice mainly made me a little better at following through with the small stuff that can so easily fall through the cracks: Writing postcards to friends. Finding time to read. Doing push-ups before bed. Small things, to be sure, but also the substance of your life.

As for the mindfulness aspect, I confess that I am still working on becoming more diligent about transcribing some of the demons in my head to the page. (My default way of dealing with stress is still to have imaginary arguments with the people who have wronged me, a habit which doesn’t do much to enhance the quality of family dinners.) However, and as any journaling veteran will be able to tell you, the mere action of crossing items off a list can have a soothing effect. It might be a stretch to call it “therapeutic,” but there’s a reason why the Bullet Journal, which was conceived by a digital designer, is a resolutely analog system. (Though, naturally, there’s also a companion app.) Part of it is just about minimizing distraction—the eternal temptation of clicking away to the next stimuli—but, more fundamentally, writing things out in longhand demands an additional level of focus.

Of course, there’s a point at which the fevered pursuit of self-optimization can start to look a little like self-indulgence. After a month of prolific logging, my Bullet Journal entries were conspicuously light on family commitments. When I proudly showed my journal to my wife one morning, she couldn’t help but observe that my day’s to-dos included the essential task of sewing a button back onto my Hawaiian shirt, but somehow didn’t mention that I was taking my kid in for a doctor visit that afternoon.

“Maybe,” she suggested, “you should write a ‘BuJo’ entry about how you’re finally going to learn how to use our Google Calendar.”