Sleep has been getting a lot of good press lately. This year alone, I’ve written about the injury-reducing power of sleep, the performance boosting effects of sleep coaching, and the restorative power of naps. As sports scientist Trent Stellingwerff told me a few years ago, sleep is “the cheapest and least painful performance intervention currently on the market.”

The only problem with sleep is that it’s so finicky: the more you want it, the harder it is to get. Mastering the art of a good night’s sleep may depend on the nuances of what you eat, the wavelength of light emitted by your phone, the temperature of your sheets, and any number of other elements of “sleep hygiene”—including the details of your workout routine.

The latest findings on the latter topic come from researchers at the University of New England, who tested the effects of morning and afternoon workouts on levels of melatonin, a hormone secreted in the brain that regulates sleepiness. Their results, ���ٳ�� International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, bolster the oft-repeated claim that working out late in the day might make it harder to fall asleep. That runs counter to the simple idea that exercise makes you tired, and thus makes you sleep better. But if you’re an after-work exerciser, don’t panic quite yet.

The new study is fairly straightforward. A group of 12 volunteers were tested on three different days: one day with no exercise, one with a workout at 9 a.m., and one with a workout at 4 p.m. The workout was a 30-minute run at 75 percent of VO2max. On each of those days, melatonin was measured with a saliva test at 8 p.m., 10 p.m., and 3 a.m. (Interestingly, the subjects apparently slept at home but “were awakened by a researcher for the 03:00 h sample collection.” I’m guessing these were undergrads living in residence—hopefully in single rooms.)

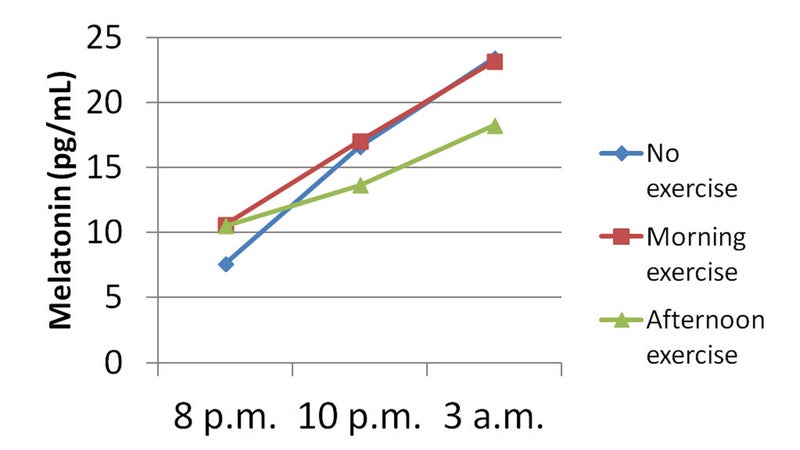

Normally melatonin levels start to rise around bedtime, helping to trigger a gradual decrease in body temperature and a rise in sleepiness, and reaching a peak around 3 a.m. Here’s what the results looked like in the study:

The main conclusion is that the afternoon exercisers had markedly lower melatonin levels at 10 p.m. and 3 a.m. compared to the morning exercisers. That, in theory, means that the afternoon exercisers will have a tougher time getting to sleep and staying asleep. End of story, right?

Only sort of. Even the researchers are suitably understated in their conclusions: the last sentence of their abstract is: “If sleep is an issue morning exercise may be preferable to afternoon exercise.” That hedging is because melatonin is just one ingredient in your personal sleep equation, and it may or may not be the dominant one. You can actually make a counterargument that a 4 p.m. workout is helpful for sleep, because it will artificially elevate your body temperature for several hours so that you get around bedtime. The drop in body temperature, like the one triggered by melatonin, cues your body to get ready for sleep. (That heating-then-cooling effect, for what it’s worth, is supposedly one of the reasons a hot bath before bedtime can help you sleep—that and the fact that you generally can’t bring your phone into the bath.)

There’s also the psychological context to consider. Are you going for a relaxing evening jog, or playing pressure-packed beer league hockey? Is a post-work gym session the way you get your mind to stop spinning about whatever stresses you encountered during your workday? These factors may be far more important that subtle changes in your melatonin levels.

Finally, one factor that isn’t discussed in the paper is how many of the subjects were “owls” versus “larks.” There’s a strong genetic basis to your chronotype, which dictates whether you tend to get up early, stay up light, or have no particular bias either way. It’s probably fair to assume that people who choose to exercise late in the day are more likely to be owls, who find the prospect of getting out of bed at 6 a.m. for a workout too horrible to consider. These people may tend to get to sleep later—but is that because of the workout, or simply a result of their circadian wiring? And more importantly, will advising them to shift their workouts to the morning rob them of morning sleep without actually helping them get to sleep earlier?

My point here isn’t that the study is useless. I do think it’s interesting to see that exercise timing seems to have an effect on melatonin levels. But I think the researchers got it right in their conclusion: this is something to consider if sleep is an issue. It’s like the whole “” thing. I believe it’s true, but I read on my iPad every night in bed, and I’m out like a light within a few minutes of turning it off—so I don’t worry about it. Similarly, the effect of afternoon or evening workouts on melatonin levels is worth thinking about—if, and only if, you’re having trouble harnessing the incredible performance-boosting powers of sleep.

My new book, , with a foreword by Malcolm Gladwell, is now available. For more, join me on and , and sign up for the Sweat Science .