DURING THE lead-up to Super Bowl XLIII, between the Arizona Cardinals and the Pittsburgh Steelers, the usual pregame parsing of the injury report took on added significance for Steelers fans because the list included Hines Ward, the team’s Super Bowl XL MVP wide receiver, and hard-hitting safety Troy Polamalu. Ward had suffered a sprained MCL in his right knee during the AFC Championship Game two weeks prior, and Polamalu had injured his calf in that week’s practice. In hopes that they could speed up their recovery, both chose to receive an experimental treatment called platelet-rich plasma (PRP) therapy. Both played in the game, the Steelers won, and Ward and Polamalu credited PRP for getting them back on the gridiron.

PRP patients: Rafel Nadal

PRP patients: Rafel Nadal

PRP patients: Rafel NadalPRP patients: Tiger Woods

PRP patients: Tiger Woods

PRP patients: Tiger WoodsSince then, the therapy, in which a person’s own blood is concentrated in a centrifuge and then injected into the wounded area, has reportedly healed injured tissue in soccer stars, baseball players, endurance athletes, marathon runners—even Tiger Woods, who famously received the blood injections in his surgically repaired left knee. Last year, tennis great Rafael Nadal underwent PRP treatment in both knees to combat tendinitis. He has since won three Grand Slam events.

All the hype surrounding the miracle injections led the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) to ban the treatments last year, fearing they could unfairly increase muscle strength. (The treatment is similar to blood doping, which is banned by WADA and involves injecting blood into veins to get the benefit of additional oxygen-carrying red blood cells.) But now, as PRP has trickled down to amateur athletes looking for a quick fix for nagging sports injuries, new science is raising doubts about the effectiveness of the procedure. Many doctors now believe that wishful thinking—also known as the placebo effect—is behind the initial positive results. Which is raising the question: Is PRP really worth $1,000 a pop?

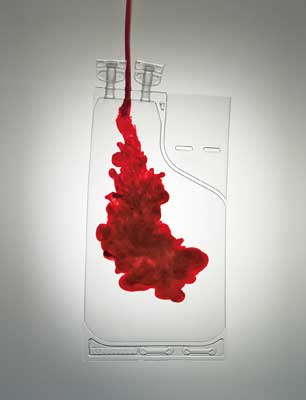

The logic behind PRP “seems quite plausible,” says Dennis Cardone, a doctor of orthopedic medicine at New York University’s Hospital for Joint Diseases, who has treated dozens of amateur athletes using PRP and is a co-author of one of the primary articles about the therapy’s effectiveness. When a tendon, muscle, or bone is first injured, a natural inflammatory response begins, and cells known as growth factors rush to the site. In conjunction with other cells, they spur healing. All of us have growth factors circulating constantly in our blood, but they’re usually found in relatively small concentrations. Put blood in a centrifuge, however, and whirl away most of the liquid and the red and white blood cells, and the remaining goo teems with concentrated growth factors. Inject this substance into a wound and, theoretically, you should speed up the body’s natural healing response.

During the initial laboratory experiments decades ago, that theory held true in testing. As a result, PRP therapy came into vogue to augment healing after certain surgical procedures, particularly oral surgery. Gradually, sports medicine latched onto the idea that PRP could augment recovery in athletes’ sore tendons and muscles, which can be slow to heal. But a study published last year in the Journal of the American Medical Association reported that PRP was no better than placebo injections of saline in treating chronic Achilles tendinopathy. Similarly, in a study published this year in the British Journal of Sports Medicine, when adults with chronic tennis elbow received the treatment, 66 percent reported a reduction in pain, but so did 72 percent of those whose shots had consisted of plain blood.

PRP has not proved to be particularly effective in acute sports injuries, either. A study presented at the 2010 meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) found no benefits from PRP in healing a shredded ACL. In that study, half of the subjects received PRP shots in their knees following surgery and half did not. After six months, there were no significant differences in the groups’ rates of healing. In response to such data, a scientific panel convened by the AAOS in February issued a statement saying that PRP’s efficacy is, at best, “unproven.” And in a telling move, WADA removed PRP intramuscular injections from its 2011 list of banned therapies.

Why PRP has not lived up to expectations remains something of a mystery. Part of the explanation may lie, of course, in the technique’s experimental nature. “There is not much consistency” in the preparation of PRP injections, Cardone says. Different techniques produce plasma with wildly different concentrations of growth factors. If an ideal formulation exists, it has yet to be discovered. Researchers also don’t know “whether the PRP even remains at the site of injection” or whether it oozes away, dissipating into the rest of the body, says Robert-Jan de Vos, M.D., a researcher at Erasmus University in the Netherlands and lead author of the Achilles tendon study.

Above all, scientists simply don’t fully understand how the body heals many types of injuries. Acute injuries and wounds elicit a robust inflammatory response, but many chronic, nagging injuries do not. There is very little inflammation in most sore tendons and ligaments. “In chronic degenerative tendon injuries,” de Vos says, various enzymes are probably being released into the tissue and surrounding area that may render them a poor environment for growth factors.

Currently, no one knows exactly how many amateur athletes have undergone PRP, because no medical agency tracks the use of the therapy. But increasingly, doctors specializing in chronic sports injuries are offering it to patients. Many times they’re offering it simply because it’s being asked for by name.

So is PRP worth it? “I would advocate a less invasive and less expensive treatment,” de Vos says. The injections can be painful, and the cost is rarely covered by insurance. Instead, exhaust all nonsurgical options first. Complete physical therapy. Consult with a sports-medicine specialist. If everything else fails and surgery looms, then consider PRP. According to Cardone, it should be “the last resort before the

very last resort.”