Bequi Livingston and the rest of the New MexicoÔÇôbased┬áSmokey Bear Hotshot crew were digging a trench through thick timber to deter the wildfire that was raging within earshot. It was 1988, and they had been dispatched to fight the┬á that were engulfing much of the national park. A crew member on watch alerted the hotshots that the fire was headed directly for their camp. Livingston, who stood four-foot-ten and 98 pounds, hoisted her packÔÇöwhich was more than half her sizeÔÇöand ran. Moments later, the meadow where they had set up camp burst into flames.

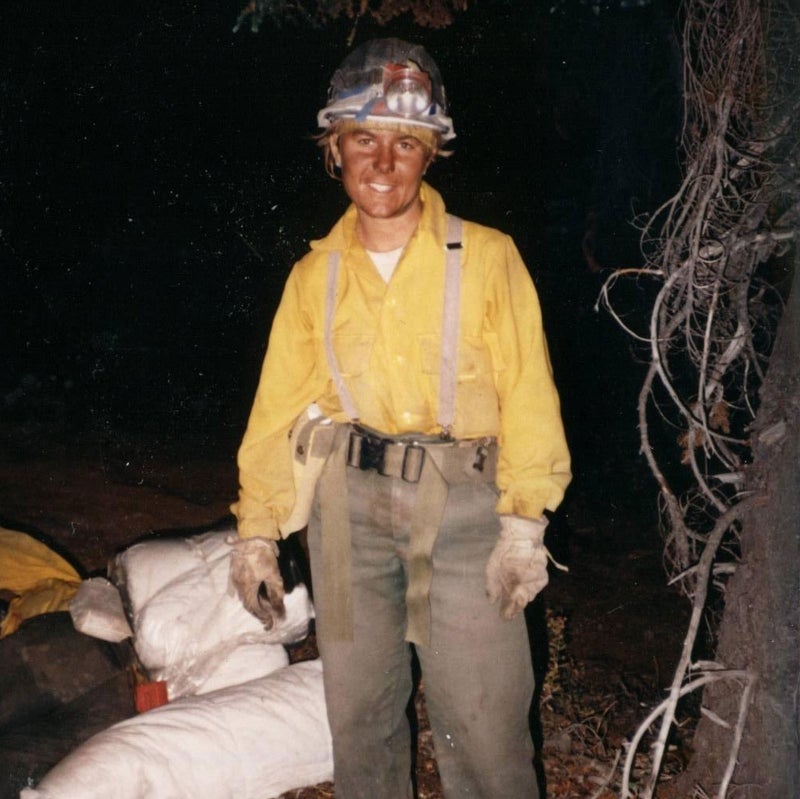

Livingston first applied to become a wildland firefighter in 1979, when she was 18. Her friends and family tried to talk her out of it, citing the dangerous nature of the job, her diminutive size, and, of course, her gender. Today many would-be women firefighters face the same skepticism.

Throughout her nearly 40 years in the field, Livingston faced down the challenges of her high-stress, physically demanding job by dedicating herself to training as hard as she could. She relied on her fitness to assert herself as one of the crew, and eventually created a program, the , to share what she learned with the women firefighters of the future. Livingston retired from the force in August, but the work she did to make firefighting more accessible to women continues to positively impact the entire community.

Livingston and her friend Margarita Philips, a retired smokejumper, had talked about creating a program to promote women in their field since 2008. They were convinced that women just needed a little extra preparation and encouragement to join the hotshot ranks. In 2011, the number of women in wildland firefighting across the country hit a 20-year low, at less than 5 percent of the force, and Washington began to pressure the U.S. Forest Service to address the disparity. When Livingston heard that the Forest Service was serious about gender equality, she pitched a solution to her supervisor: a program where women interested in firefighting could come together to learn and train before committing to joining a crew.

Livingston launched the camps, which are held all over the country, in the spring of 2012. Participants get paid by the Forest Service for their training, and each week-long session combines on-the-ground skills development with classroom learning. Daily tasks include mimicking fieldwork, like hiking in full turnout gear or running up a steep hill while dragging a heavy water hose. The classroom portion covers subjects like fire behavior, ecology, and incident command.

The goal is for the instructorsÔÇöexperienced firefightersÔÇöto┬ágive participants the tools they need to move successfully through the application process and earn a spot on a fire crew. For instance,┬áparticipants┬áare┬ámatched with a personal trainer for an hour of conditioning each day┬áto ensure theyÔÇÖll be┬áready for the work capacity test that all Forest Service firefighters must pass: hike three miles wearing a 45-pound weighted vest in under 45 minutes.┬áLivingston┬áset a good example for prospective recruits. Though┬áthe test is┬áonly required once, she┬ávolunteered to take it┬áevery year until she retired. She passed every time.

But physical preparedness only goes so far: Livingston still faced┬ábullying and harassment from male firefighters. On one assignment, members of LivingstonÔÇÖs crew weighted her pack with rocks to slow her down. On another occasion, an all-male crew challenged LivingstonÔÇÖs coed hotshots to a miles-long hike in an attempt to prove an all-male crew could beat out LivingstonÔÇÖs. (It┬ácouldnÔÇÖt.) The physical┬áand mental demands of the job wore on her, and Livingston repressed her anxiety and alienation. ÔÇťI spent so much of my career trying desperately to help others that I was neglecting the little things in my health and life even when they were whispering to me,ÔÇŁ Livingston said.

Informed by┬áher own experiences, Livingston wrote elements of self-care and mental health into the boot-camp curriculum, developing a more holistic approach to fireline preparedness that emphasizes mental well-being alongside physical fitness. Firefighters are taught to recognize the┬ásigns and symptoms of mental illness like PTSD, and theyÔÇÖre encouraged to seek help if they need it.

After a career of serving others, Livingston is taking a step back to focus on herself. She no longer runs the program, and most of her current exercise is walking and yoga. Mostly┬áshe wants to enjoy her home state of New Mexico┬áand the land she spent so much of her career protecting. SheÔÇÖs passed the torch┬áto a new generation of firefighters:┬á120 women participated in the southwestern regionÔÇÖs boot camp this year, an all-time high.┬á