HEART

One reason exercise gets more difficult with age: arteries lose elastin and begin to stiffen, which means blood doesn't move as efficiently and less oxygen reaches muscles. Earlier this year, researchers at the University of Pittsburgh grew stretchy blood vessels from cells taken out of young baboons. Lab-grown tissues could one day replace severely blocked arteries in people with heart diseaseÔÇöor the stiffening arteries of older athletes.

BONES

The simplest way to build strong bones? Try some good vibrations. In recent studies, mice that stood on a vibrating platform developed thicker, healthier bonesÔÇöand far less body fatÔÇöthan unshimmied rodents. Researchers think the shaking causes stem cells in bone marrow to differentiate into bone tissue instead of fat. Fortunately, many gyms already have vibration platforms. Note: mild vibes are all it takes.

KNEES

One of the more vexing challenges of cartilage-replacement surgery is getting the new stuff to stay in place. A possible solution: magnets! In a recent Japanese study, scientists implanted microscopic magnets at the base of damaged rat knees, then injected cartilage cells that had been mixed with magnetized iron oxide. The magnetized cells glommed onto the site in 48 hours and began dividing and multiplying.

TENDONS

Ever since Tiger Woods admitted to using platelet-rich plasma, or PRP, last year to help heal his mangled knees, the therapy has become wildly popular for a range of problems. The treatment requires siphoning blood (yours), centrifuging it until it's a viscous goop packed with platelets (cell fragments involved in blood clotting) and growth factors (which cause cells to divide and multiply), and injecting it into sore tissue. In early tests, treated tendons became thicker and strongerÔÇöso much so that the International Olympic Committee banned the practice for uninjured athletes.

ANKLES

Sprains are among the most common sports injuries and can cause joints to become unstable and arthritic. In the past, surgeons would fuse a repeatedly injured ankle, but early reports suggest replacementsÔÇösome made of metal and polyethyleneÔÇörotate and respond almost as well as the real thing.

To View the pdf,

.

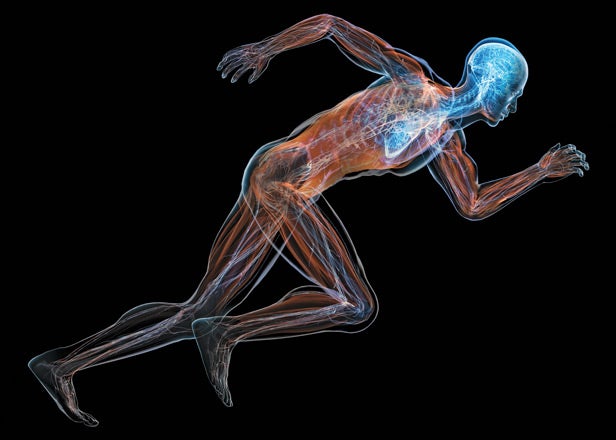

Future of Human Performance

The future of human performance

The future of human performanceEYES

Robovision is coming soon. In 2009, surgeons at Columbia University Medical Center in New York implanted an electronic retina in the eye of a blind woman, allowing her to “see” through a video camera mounted on eyeglasses. A microprocessor converted the digital feed to electronic signals and sent them to the retina, which stimulated neurons in her visual cortex to create mental images.

LUNGS

Time to become a better breather. In a 2010 study at Indiana University, cyclists puffed into a handheld machine that huffed back, providing respiratory resistance and strengthening the diaphragm. After six weeks, the riders required up to 4 percent less oxygen to pedal at a given pace. Respiratory-training devices of varying quality are already available and could soon show up at your local gym.

SKIN

Researchers at Stanford University have developed a microthin electronic hide made of pliable polymers and carbon. Nano-transistors embedded in the fabric and powered by stretchable solar-collection cells sense touch, as well as the presence of proteins that might indicate disease. The material will probably be used in clothing first but could someday replace damaged skin.

STOMACH

Fasted trainingÔÇöavoiding carbohydrates before and during a workoutÔÇöis a sports-nutrition fad with solid scientific support. In a six-week study in January, cyclists who rode without eating converted fat to fuel much more efficiently than cyclists who ate before and during training. The fasted riders also maintained even blood-sugar levels during long rides, while cyclists accustomed to eating experienced abrupt drops in blood sugar when forced to go without. The benefits could be especially significant during races, when many athletes eat sparingly or not at all.

MUSCLES

Scientists at the University of Colorado may have found a fountain of youth for muscles. Typically, once you pass 30 your muscles are slower to repair themselves, so they don’t recover as well after workouts or gain strength as effectively during training. But when researchers injected stem cells from the muscles of healthy mice into mice with injured leg muscles, not only did the injuries heal rapidly but the muscles remained vigorous for the rest of the mice’s lives. The scientists are now hoping to test the procedure with humans.

To View the pdf,

.

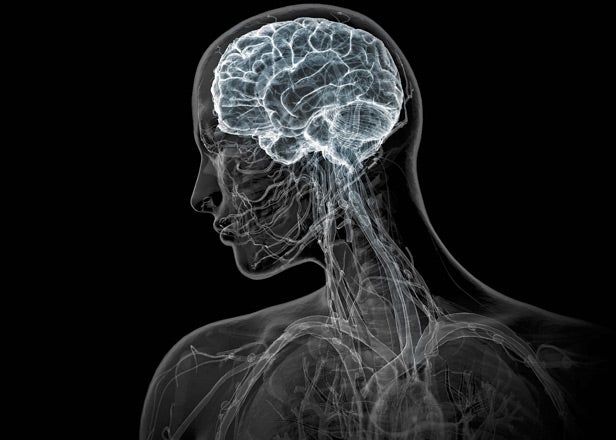

BRAIN

One lesser-known benefit of training: it makes you smarter. How? Exercise boosts production of the poetically named neural protein noggin, which results in healthier stem cells in the brain. Without enough noggin, neural cells stop dividing and don’t create new tissue: your brain literally shrinks. Need more convincing? Scientists synthesized the stuff and injected it into the brains of mice, which subsequently aced rodent intelligence tests.

NERVES

Help may be on the way for athletes with spinal injuries. Scientists are working on a tiny wireless device that, when implanted in the brain, can send electrical impulses signaling movement directly to artificial limbs, bypassing damaged nervous systems. The gadget is being tested on monkeys, and a similar technology could someday allow paralyzed humans to regain control of their bodies.

MOUTH

You are what your parents (and grandparents) ate, according to epigenetics, the newest branch of gene research. Diet turns certain genes on or off and changes how others express proteins, affecting metabolism and muscle functionÔÇöinstructions that can be transmitted to offspring. When male mice were fattened on high-calorie chow, they sired pups predisposed to obesity. Similarly, when pregnant mice were underfed, their offspring were born with metabolic abnormalities that, a generation later, appeared in their children’s babies.

To View the pdf,

.