Something was wrong with Norwegian superstar rower Olaf Tufte. After winning the bronze medal in the 2002 world championships in single sculls, Tufte turned in poor results in several early-season 2003 races, even though his training schedule hadn’t changed. His coaches couldn’t figure it out until they looked at his heart-rate data—and his garage.

“His problem was that he got a cool new boat,” says Stephen Seiler, an American exercise scientist teaching at the University of Agder, in Kristiansand, Norway. “He was so excited about it that he peppered his easy days with a few semi-hard bursts.” As it turned out, even those moderately challenging efforts were enough to sabotage Tufte’s recovery days and send his performance into a downward spiral. Or, as Seiler likes to put it, “he got sucked into the black hole.”

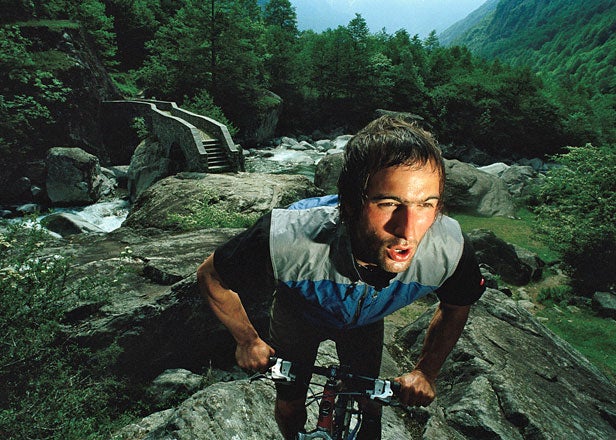

“The black hole” is Seiler’s term for a nightmare training zone that can be hard to resist—an enjoyable, moderately taxing workout intensity that falls somewhere between a piece-of-cake recovery pace and a hellishly intense interval session. It’s vigorous but not aerobically painful—which is why so many athletes are sucked into its vortex. When most people go for, say, a brisk 30-minute , they’re often in this zone. These moderate-intensity workouts are fine for beginners who are just interested in building their fitness foundation, but not if you’re serious about improving: middle-of-the-dial efforts just produce middle-of-the-pack results. “To get better, you have to go really hard and really easy—but not in between,” Seiler says.

The theory of the fitness black hole has been floating around among elite-level coaches for years, but Seiler was the first to back it up with research. After spending much of the past decade observing training plans, he noticed a pattern among successful athletes: a lot of high- and very low-intensity workouts but few moderate ones. In 2007, Seiler and a Spanish sports scientist and elite running coach, Jonathan Esteve-Lanao, co-authored a study published in The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research that suggested that the pattern wasn’t a coincidence. Over five months, 12 of Esteve-Lanao’s runners split into two groups: One group of six spent 25 percent of their time doing moderate-intensity black-hole training, while the other six devoted only 12 percent of their time to those workouts and spent the extra time doing really slow recovery training. The latter group improved their 6.5-mile race time by an average of 36 seconds more than the group doing more black-hole workouts.

“The black hole is poison,” says Carl Foster, a professor of exercise and sports science at the University of Wisconsin–LaCrosse who has co-authored two research studies on the topic with Seiler. The danger zone, he says, is just above the intensity where your body shifts from aerobic to anaerobic training, a tipping point known as your lactate threshold. (See “Find Your No Zone,”.) If you train well above it, you’ll put enough stress on your body to make it adapt and become stronger. Training too close to your threshold, says Foster, “won’t get you as strong as intervals but will leave you just as fatigued.” Worse, if you pick up the pace on a day that was supposed to be your recovery day, your body won’t get the recharge it needs, and you won’t be at full power for your next hard workout.

That’s a lesson Olaf Tufte learned quickly. After being told to cool it with his new boat, he overcame his poor early season to take the gold at the 2003 world championships and went on to win the Olympic gold medal in single sculls in both Athens and in Beijing.

“It’s simple. If you want to be your best, go hard and go easy,” says Foster, “and don’t go in the middle.”

Find Your No Zone

The black hole is a narrow no-go range, a span of about seven to ten heartbeats per minute. Here’s how to figure out where it is for you.

Spot Check

The simplest way to estimate your black-hole zone is to do the “talk test.” Go for a run or a ride with a heart-rate monitor and a buddy, and slowly pick up the pace. Have a conversation or, if alone, say the Pledge of Allegiance. At the point where it becomes difficult to talk in complete sentences, check your heart rate. That’s pretty close to your lactate threshold. Take that rate, add 6 percent, and that’s the range to steer clear of. (For example, if your threshold is 150 bpm, your black hole will be 150 to 160 bpm.) Next, set your heart-rate monitor to beep when you get close to that zone, so you know when to back off.

Full Test

To get a more precise sense of your black-hole zone, follow these steps:

1. Do a 30-minute all-out effort wearing a heart-rate monitor.

2. Average your heart rate over the last 20 minutes of the workout. That number is your lactate threshold.

3. Take that heart rate, add 6 percent, and stay out of the range in between.

Easy days should feel nothing like your hard days. Here’s how to do each one right.

Recovery Days

It’s easy to unconsciously pick up the pace on recovery days, especially if you’re a time-crunched athlete. But if the pace feels boring and uselessly slow, it’s probably perfect. “It’s almost physically impossible, unless you’re a world-class marathoner, to run your long runs or recovery runs too slow,” says Mikael Hanson, president of Enhance Sports, a multisport coaching outfit in New York City.

The Plan

Runners: The pace for your long runs should be 1:30 to 2 minutes per mile slower than your 10K race pace, and your recovery runs should be even slower than that. Pick up the pace, even for a brief period, and you’re just logging junk miles. One way to stay honest: Wear a warm-up suit—if you sweat, you’re pushing too hard. You should finish feeling refreshed, not winded.

Cyclists: Do your 60-to-90-minute recovery rides in the small chainring, at 100-plus RPM. Don’t worry about speed. Take in the view. If you’re highly competitive, don’t train with faster athletes on your recovery days.

Hard Training Days

If you don’t push it hard enough during high-intensity training, you’re probably going to hit a plateau. “You have to go into the uncomfortable zone,” Hanson says.

The Plan

Runners: Do your high-intensity training and intervals at or over your 5K or 10K race pace. It should feel intensely hard, not “comfortably hard,” in order to trigger your body to grow stronger. Follow up these killer workouts with a rest day or recovery day.

Cyclists: Do your intervals and loops at a higher intensity than your 40K race pace. You should feel worked. Take it really easy the next day.