Whenever I hear about researchers on the cusp of developing an “” that would replicate the benefits of physical activity, I think of of 30,000 runners, which found that long-term risk of glaucoma was inversely proportional to weekly running mileage and best 10K time. Other studies of the same cohort found similar relationships for , , and . Someone may eventually develop a pill that boosts my VO2max—but will it also and ?

It’s in that spirit of “” that I present the to my hypothetical infomercial on the benefits of exercise. A research team led by Heidi VanRavenhorst-Bell of Wichita State University has demonstrated that exercise is associated with greater tongue strength and tongue endurance. And not all exercise is created equal. Weightlifters have greater maximal tongue strength; runners have greater tongue endurance. (Running author Scott Douglas already made the requisite kissing joke , so I’ll pass on it.)

I’ll admit that this initially seemed mostly like a novelty good for a few laughs. But I read the study out of curiosity, and came away with a greater respect for the importance of tongue muscle research—which, it turns out, is with hundreds of studies in recent years.

Good tongue muscles are crucial for “upper airway patency,” which relates to your ability to keep your airways open while you’re asleep. If the slow-twitch muscle fibers at the back of your tongue lack endurance, it will raise your risk of and . And tongue strength, particularly in the fast-twitch fibers toward the front of the tongue, is also crucial for swallowing. Most people’s tongues get weaker as they age, which can eventually lead to dysphagia, or . So in a perfect world, you’d maintain great endurance at the rear of your tongue to avoid airway problems, and great strength at the front of your tongue to avoid swallowing problems.

In a , VanRavenhorst-Bell assessed tongue strength and endurance in 48 volunteers, and found that those classified as highly active scored higher on the tongue measures than their sedentary peers. The effect was more pronounced in people in their 60s than people in their 20s, suggesting that regular exercise helps stave off the usual age-related decline in tongue muscle.

How do you assess tongue muscle, I hear you wondering? Using the Iowa Oral Performance Instrument, of course. This basically involves sticking an air-filled bulb in your mouth and using your tongue to press it against the roof of your mouth; the machine measures how much pressure you’re able to exert. Endurance, in VanRavenhorst-Bell’s research, is assessed as the length of time you can sustain 50 percent of your personal max pressure. You can position the bulb in different places to assess the strength of different parts of the tongue. There’s a nifty little GIF illustrating the device in action on , which I promise is worth the click.

For the new study, VanRavenhorst-Bell and her colleagues recruited 21 weightlifters and 23 runners, each of whom engaged in their preferred activity at least four times a week. They hypothesized that the rhythmic panting of endurance runners would produce greater tongue endurance, particularly toward the back of the tongue which is responsible for maintaining open airways. The weightlifters, in contrast, would predominantly use the front of the tongue to produce forceful inhales and exhales, resulting in greater strength at the front of the tongue.

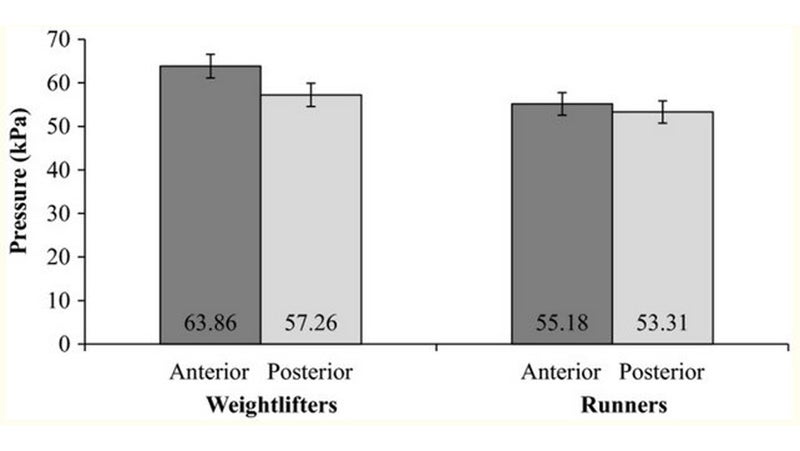

And that’s more or less what they found, as it turns out. When you look at maximum tongue strength, there’s no significant difference between the groups at the posterior (back) of the tongue, but the weightlifters are stronger at the anterior (front) of the tongue. Here’s what those results looked like:

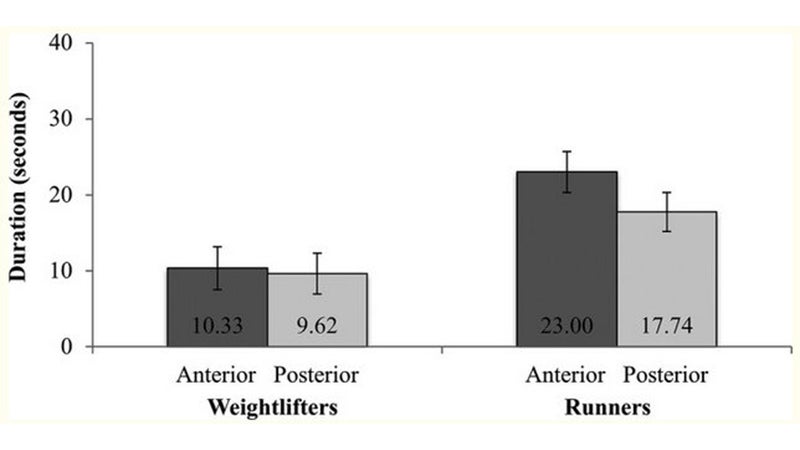

For tongue endurance, which again was the length of time the subjects could maintain 50 percent of their max pressure, runners had much better endurance at both the front and back of the tongue:

There are a few caveats to point out here. One is that the slightly greater tongue strength in the weightlifters may simply be a result of “the size of orofacial features.” In other words, weightlifters tend to have bigger heads and bigger mouths than runners, so maybe that’s why their tongues are stronger. Further research awaits, no doubt. Another is that the endurance measurements may be skewed by the fact that the weightlifters were stronger overall, meaning they had to sustain a greater pressure during the endurance test. But the strength differences were very subtle compared to the endurance differences, so that’s unlikely to be a major factor.

So what, other than storing it up for cocktail-party season, do we do with this tidbit of information? We can now say a little more confidently that exercise, particularly endurance exercise, may be useful in preventing and perhaps treating conditions like sleep apnea and dysphagia. But we already knew that for other reasons. Knowing that dropping my 10K PR might lower my risk of glaucoma never altered my training, and I doubt it changed anyone else’s habits, either. I suspect the same will be true of our newfound understanding of runner’s tongue.

Still, I think that adding to exercise’s but-wait-there’s-more list is worthwhile, because it reinforces the message that there’s way, way more to physical activity than we’ve yet grasped. Forget about shortcuts; skip the pharmaceutical alternatives. Your tongue, like the rest of your body, was made to move.

My new book, , with a foreword by Malcolm Gladwell, is now available. For more, join me on and , and sign up for the Sweat Science .