The 2010 Chicago Marathon came down to a duel between two East Africans: Kenyan Sammy Wanjiru and Ethiopian Tsegaye Kebede. The men were ranked one and two in the world, respectively, and their rivalry was fierce. On the line were a prestigious victory and a half-million-dollar purse.

Kebede led from the start. Wanjiru was battling a nagging knee injury, and the Ethiopian easily fended off his repeated attacks. , with a lead of several yards, Kebede’s form looked good—he was running tall, shoulders square, arms pumping rhythmically. Wanjiru, by contrast, ran with flailing arms, his face stretched in pain. Then, on the ascent, with less than half a mile to go, Wanjiru launched what appeared to be a hopeless last surge. This time, however, Kebede couldn’t respond. The Kenyan inexplicably ground ahead, winning by 19 seconds.

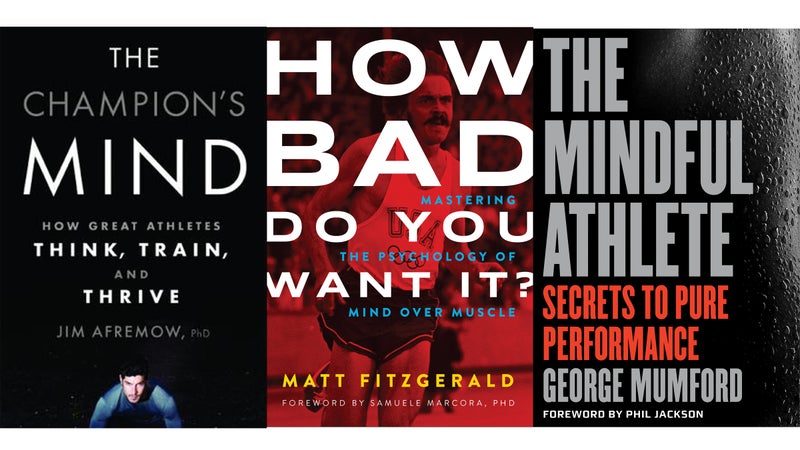

Wanjiru’s effort in Chicago is just one high-profile example of the mind pushing past apparent physical limits, a phenomenon that has been the subject of much recent scrutiny. Mindset, also known as mindfulness, coaching has been around for a while, but it’s long been a fuzzy dimension of sports psychology focused largely on visualization, relaxation, and positive thinking: imagining yourself dunking a basketball, say, or winning a race. While this has proven to be helpful, recent research examining the mind’s role in athletic performance has yielded compelling insights for athletes of all levels. The studies have led to books by Matt Fitzgerald, Jim Afremow, and George Mumford that look to share the new understandings.

($16, Rodale) is a little behind the latest research on mindset training. It takes six chapters to get past the pep talks on self-confidence (most serious athletes I know are plenty confident and have heard most of this before) and hit on the new frontier: meditation and its ability to rewire the brain. He points to a 2011 study in the journal Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging showing that 30 minutes of daily meditation for eight weeks rewired gray matter to alleviate stress and enhance focus and concentration.

This thread gets picked up at length in Mumford’s , ($22, Parallax), an extended discussion of Zen Buddhism’s role in athletic performance. Mumford deployed this approach with Phil Jackson and the Chicago Bulls, among others, and he got impressive results. But while The Mindful Athlete is rich in discussion, it’s thin on science. Which is, after all, the source of the new wisdom. This is where Fitzgerald’s ($19, VeloPress) shines.

Fitzgerald’s book, which kicks off with the Kebede-Wanjiru battle, addresses the growing field of psychobiology, a branch of behavioral neuroscience, and its recent interest in athletic performance. Central to the discussion is the notion of perceived effort. As it sounds, PE is essentially your sense of how hard you’re working, whether it’s striving for six-minute miles or trying to hang with the lead group of cyclists on a long climb. Though the finding is still subject to debate, some researchers now contend that fatigue is mainly a mental phenomenon, not a physical one.

As Fitzgerald writes: “Exhaustion occurs during real-world endurance competition not when the body encounters a hard physical limit such as total glycogen depletion but rather when the athlete experiences the maximum level of perceived effort he is willing or able to tolerate.… The inexorable slowing is not mechanistic, like a car running out of gas, but voluntary.”

Because fatigue may reside mostly in the mind, it can be influenced by numerous factors. In one oft-cited 2014 experiment, led by neuroscientist Samuele Marcora at the University of Kent, two groups of cyclists pedaling stationary bikes were shown a series of subliminal images. The group who viewed happy faces were able to ride, on average, three minutes longer than the group who saw sad faces. Similar results occurred when the riders were flashed upbeat words. Though the physical markers of exertion—heart rate, blood-glucose levels—rose by the same degree, the riders’ sense of the effort they were expending was different. Three minutes is a big jump, and champion athletes have, of course, learned to leverage this kind of positivity. Distance runner Haile Gebrselassie and triathlete Natascha Badmann are renowned for smiling when they compete.

A recurring theme through all three books is managing stress and anxiety. These nebulous forces directly impact performance, sometimes in insidious ways, and they can range from pre-race jitters to chronic thoughts of inadequacy. Diligent training builds confidence through physical adaptation; even more than that, it fosters resilience for the stress of competition. But sometimes our best effort requires more than a well-constructed workout plan. It may require understanding and managing whatever psychological demons threaten to make our hard work feel even harder.

All three authors seem to agree that your head requires the same kind of dedicated work as your body. Alas, none of them offer any sort of comprehensive mindset-training program; rather, tidbits of advice, like breathing exercises and drills to improve concentration, are embedded in the chapters. The takeaway comes down to how well an athlete can identify recurring pitfalls and pull focus away from them: Do you go out too strong? Are your starting-line nerves debilitating? And so on. Mental fitness, says Fitzgerald, means “becoming your own sports psychologist” and developing coping mechanisms to help you suffer better.

Which, while not entirely satisfying, is a good start. With traditional training strategies for physical fitness, nutrition, and sleep becoming more dialed and demystified, the mind is the next frontier for significant performance gains.