Researchers in Norway just published a study comparing the effectiveness of a “long, traditional” warm-up with a “short, specific” one for cross-country skiing sprints. The warm-up is one of those things that, as Gina Kolata pointed out in an a decade ago, is “more based on trial and error than on science.” But in the years since Kolata’s article, sports scientists have been hard at work refining their understanding of the physiological process underlying a successful pre-race routine.

The shorter protocol in the Norwegian study, which was , drew on this new science. Instead of 30 minutes of mostly easy skiing interspersed with five minutes of moderate and three minutes of high-intensity effort, the skiers simply did eight progressively harder 100-meter sprints with a minute of rest. The idea was to harness the metabolic and neuromuscular benefits of raising muscle temperature while minimizing the effects of cumulative fatigue.

The result: no difference in performance in a 1.3-kilometer sprint, which takes about 3.5 minutes. No difference in heart rate, lactate, or perceived exertion. The choice of warm-up simply didn’t matter.

One way of interpreting these results is that you can save time and energy with the short warm-up. Given that sprint skiers do four of these sprints over the course of a few hours during competitions, saving energy during warm-ups seems worthwhile. But the null result might also make a cynic wonder whether the warm-up really matters at all.

As it happens, in the same journal tests this question more directly. Researchers at the European University of Madrid compared two warm-up protocols before a 20-minute cycling time trial. One involved cycling for 10 minutes at 60 percent of VO2 max; the other involved 5 minutes at the same intensity, followed by three all-out 10-second sprints. Again, the shorter warm-up with sprints aimed to maximize muscle temperature benefits while triggering an effect called (PAP), a supposed enhancement of strength and speed following intense muscle contractions. And again, there was no difference in cycling performance between the two warm-ups.

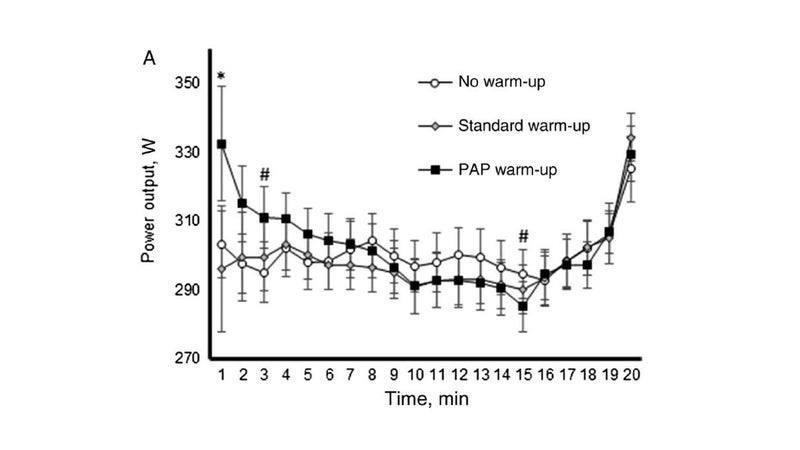

But this time, there was an additional twist. The study also included a control condition, in which the cyclists did no warm-up whatsoever. Contrary to what every athlete’s instincts are screaming, there was also no difference in performance in the no-warm-up group. The graph below shows what the average power during the 20-minute trial looked like for each cyclist in the three conditions. Some did better (i.e. had a higher power output) with no warm-up, while others did worse. But overall (as shown by the bars) there was no clear trend.

Let me back up here for a moment before I get swamped with angry feedback. There have been tons of warm-up studies over the years— cited 170 references—and lots of them have found performance benefits. But the strongest evidence is for sprint and power sports, not endurance events. One found no significant benefit of warming up before a 30-minute running trial; found no benefit of either a short or long warm-up before a 5K cycling trial.

Interestingly, the new Spanish study included a jumping test in its protocol—and the warm-ups did work for that. The standard warm-up boosted jump height by 9.7 percent, and the shorter PAP warm-up increased it by 12.9 percent. So it’s not that the warm-up was totally ineffective; it’s just that it didn’t make them faster in the 20-minute trial.

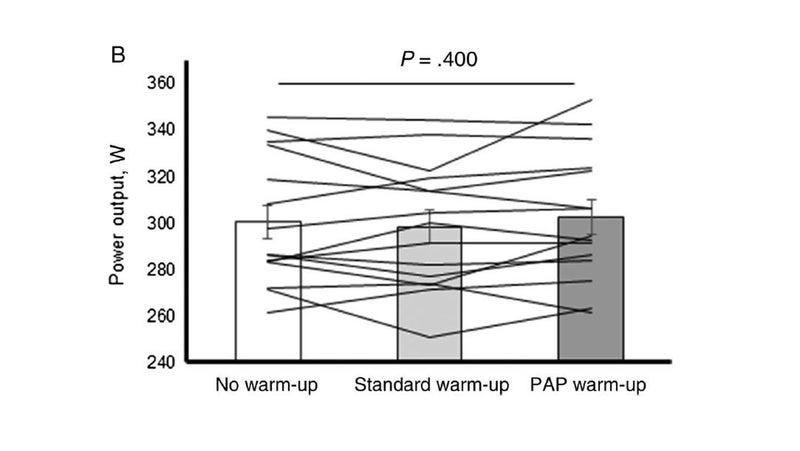

Even within the cycling trial, there were some nuances. Here’s what the pacing profiles looked like for the three conditions. The cyclists started considerably faster after the PAP warm-up, which included those brief all-out sprints:

The quick start didn’t translate to a faster overall performance, as the initial edge was paid back over time (there’s no free lunch!). But in a competitive context, racing against real people rather than alone in the lab, being prepared to start fast may be an advantage. There’s robust evidence that including some short bursts of relatively intense “priming” exercise revs up your oxygen delivery system so that you accumulate a smaller oxygen debt in the frantic initial moments of a race. If you’re running an 800-meter race that lasts somewhere around two minutes, that could offer you a crucial edge. But does the same apply in, say, a 10K? Or a marathon? Or the Tour de France?

There are a couple of other caveats to consider. One is the risk of injury. That’s actually the main reason most of us choose to warm up before workouts: increasing the temperature of your muscles and tendons makes them more supple, in the same way that play-dough softens when you warm it in your hand. While the evidence that this actually reduces injury risk is , it seems like a reasonable supposition, especially for high-intensity or explosive sports. But again, it’s far less clear that launching into your marathon race pace without a warm-up is all that dangerous.

The other caveat is psychological. None of the athletes I know would feel comfortable and confident about competing with no warm-up at all. That may simply be because it’s what they’re used to and what they’ve always been taught. But it may also be that something about the warm-up process helps them narrow their focus and get into the right headspace for competition. That may be a key contrast between research studies, where the no-warm-up group gets to sit quietly for the same duration as a warm-up would take, and the real world, where competing without a warm-up is often the result of arriving late or some other logistical disaster that leaves the athlete frazzled.

If you want to make the case that warm-ups are important, there’s plenty of mechanistic research to bolster your argument. The Norwegian researchers cite a long list of benefits related to increasing muscle temperature, including more rapid metabolic reactions, decreased stiffness of muscles and joints, increased nerve conduction rate, and others. There are also benefits that don’t have anything to do with temperature, like dilated blood vessels that increase blood flow to your muscles.

There’s good evidence for all those changes. But the researchers go on to point out that warm-ups also come with a cost: they burn up some of your finite energy reserves, and may leave you with lingering traces of metabolic fatigue. In hot conditions, raising your core temperature prematurely may slow you down sooner. Getting the balance right between these competing effects may be trickier that we realize. And that’s especially true for longer endurance events, including the 20-minute time trial in the Spanish study. The longer the event, the less you gain from being metabolically optimized right from the start of the race, and the more you lose from burning through some of your stored energy.

In the end, I’m not advocating the end of warming up. (So please, delete that hate mail!) But I think it’s useful to have a realistic sense of how important it is, and not let it become an extra source of stress. In races longer than, say, half an hour, the performance effect seems to be subtle at best. So by all means go through your usual routine if it helps get you in the right headspace. But if something interferes with the routine, whether it’s a traffic jam, the packed corral at a big marathon, or the tiny call-room at the Olympic Games, don’t sweat it.

For more Sweat Science, join me on �����Ի� , sign up for the e, and check out my book .