Screw quick fixes and fad diets. Dedicate 12 weeks to this back-to-basics plan, and you can have real, lasting, all-around health and fitness. My story is living proof.

The Guinea Pig

8.25.07

Race Day, Part 1

A few months ago I decided I'd had enough of physical mediocrity. This isn't to imply that I'm of the fat-oaf variety. Despite my self-destructive proclivities, I regularly jog, hit the heavy bag, and lift weights.

But I wanted the kind of all-around fitness that would enable me to get up a climbing wall, try surfing on a whim, motor through a full-on pickup basketball game without being hobbled the next day, or maybe even complete a triathlon. That's why I left my Manhattan apartment nine weeks ago for the mountains of Park City, UtahÔÇöwhy I endured a summer of exhaustion and pain, dished out by a personal coach. Simply to answer the question: Can I change from athletic into an athlete?

I'm about to find out.

A voice booms through the air.

“Are you ready?!”

It's the announcer at my first-ever triathlon, perched on a rocky ledge in Utah's , 50 feet from the water.

I pull my goggles over my eyes and take a deep breath.

“Five!” yells the announcer.

Did I train enough? I ask myself.

“Four!”

I never should have taken that time off for my buddy's wedding.

“Three!”

Those buoys look awfully far.

“Two!”

What's the worst that could happen?

“One!”

Oh, shit …

“Go!”

6.18.07

The Beginning

Four days after arriving in Salt Lake City, I meet at the Utah Jazz practice facility. McKown has agreed to train me, and our first day will involve a hike. “A little test,” he says. “See where you're at.”

The sun shines mercilessly as we trudge up Mailman Ridge, a trail named for retired Jazz All-Star Karl Malone. My lungs grasp for air a mile above sea level. We cover 2.33 miles in 47 minutes. Good time, says McKown, considering the 93-degree heat. Handing me an AdvoCare recovery drink, he launches into a disquisition on stride length, efficiency, lung capacity, recovery time, genetic potential, and perceived exertion rates. My stomach churns.

He hands me a stack of papers detailing the training regimen he tailored specifically for me. Running, swimming, and biking two to three days a week; strength training two to three days a week; sprint and endurance work one to two days a week; core work every other day; and daily stretching.

6.25.07

I Only Kinda Suck

I escape the kiln that is Salt Lake City for a friend's Park City digs and begin training in earnest. I start with what I know best, the run, and spend much of the paltry 25 minutes walking and wheezing. I manage only 2.79 miles, according to my Garmin GPS watch. The following day, dressed in gym shorts, a T-shirt, and sneakers, I cover 10.41 miles on a creaky steel loaner mountain bike. I don't stop. I don't suffer. Encouraging.

6.28.07

Out of My Element

My first swim in eight years is not pretty. Flailing. Inhaling water. I manage two laps of the 25-yard pool at the Park City Racquet Club and take a break. After six laps, I haul myself out and assess. I'll require some coaching.

7.04.07

Baby Steps

I join nearly 1,000 others for the Park City July 4 “Fun Run,” a 5K race along rolling hills behind a golf course.

I don't like running. My regular jogs along the East River are done solely to stave off a widening midsection. Today, however, the experience is relatively pleasant as I settle into a respectable 8:20-per-mile pace. Despite only ten days of exercise, already I sense stronger legs, a tighter midsection, better stamina. I've dropped seven pounds, down to 148 (I'm five ten).

The finish line is within shouting distance when a competitor passes me. It's a womanÔÇömy age, maybe older. She's pushing a stroller with two toddlers inside.

McKown says my transformation will come not in leaps but in small steps. Today is a step.

7.05.07

Calmer Waters

PCRC swim instructor Brittany Coyle paces poolside. A 20-year-old business major, she has agreed to teach me swimming fundamentals and devise a training plan. As I begin the 1,700-meter workout, I ruminate over her adviceÔÇökick less frequently, relax my arms when possible, keep my head down.

There is something to be said for human interaction during solitary pursuits. I'll take warm blood over books and magazines any day. Triathlon literature only proves that I've undertrained, overtrained, bought the wrong gear, or adopted the wrong attitude. I prefer instant feedback.

Near the end of the swim, I develop a rhythm. My lats are tight and my breath short, but I feel goodÔÇölike I might not drown.

7.12.07

Gut Check

Almost a month in. Biking 13 miles presents little problem, my running splits are now under 8:15 per mile, and I no longer envision authorities dragging the bottom of the reservoir. I'm up with the magpies at dawn, to bed with Jon Stewart at night. I eat five to six small meals daily. I read, write letters, rest. I've forgotten the taste of beer. I weigh 145.

Training is no longer just a daily accessory; it's a necessity. Everything revolves around it.

Of course, all is not gilded on my path. There's random pain. A tender Achilles tendon, a clicking shoulder, and sharp stabbing beneath the ball of my right foot. Also, to be honest, I'm a bit bored.

In need of a lift, I call McKown. I don't mention my maladies, but he senses something's amiss. Later, I receive an e-mail: “Your fitness is at a level where you could go out today and complete a triathlon. But just completing is no longer good enough. Think about winningÔÇöwhether it's beating the guy next to you, all other first-timers, or everyone in your age group.” He closes by paraphrasing legendary distance runner Steve Prefontaine: “Some people race to win. I race to see who has the most guts.”

7.13.07

All Together. Now.

I attempt my first mock triathlon. Since my race looms a mere six weeks away, I make a personal declaration of war, unveiling my titanium-blue Speedo. The strategy helps. Sort of. The 300-meter swim breezes by, but the five-mile trial rideÔÇöI'm still using a mountain bikeÔÇöleaves me winded, and I cramp up during the run. Incremental, perhaps. But it's progress. Two months ago I wouldn't have been able to imagine thisÔÇöor the Speedo. Now that I know I can do it, it's time to do it well. Intervals during the runs. Sprints in the pool. An actual road bike.

7.30.07

On the Road

I coast into the Cole Sport parking lot on a loaner road bike and, finally, in spandex cycling gear. My first group ride. A bit unnerved, I explain my project to Scott Ford, a 37-year-old triathlon veteran who heads up the local outdoor retailer's bike team, and ask for advice. “In the swim you just try to survive,” he says. “The bike should be fun, a time to recover. The run? Lots of suffering. Just don't stop.”

About 20 cyclists show for the weekly ride, and we set off on a 22-mile loop. We start off at an easy pace that allows me to pass, draft, talk, and experiment with the gears. By mile seven I'm antsy, aching to take off. But around mile 14, I'm simply aching as we hit an interminable, desolate, uphill stretch alongside Old Highway 40. The climb splits the crew into two groups, a mile of asphalt between them. I can't catch the leaders, but, encouragingly, I don't fall back with the experienced riders in the back group, either. It's just me and the road. Brutal. But it's a good brutal.

8.08.07

The Breakdown

I sit in the darkness of my house, trying to cope with the realization that my body has turned to mulch, my will blown away.

“Six weeks is the magic number for hitting the wall,” McKown explains as he walks through the front door for a scheduled visit. “Your body's made major adaptations; now it's settling. But we're gonna get you past this.”

He explains that the body needs variety. “Active rest”ÔÇölight workoutsÔÇöwill ease the transition to the next plateau. Triathlon training is notorious for making people obsessive. I should step back sans guilt.

We drive to a nearby restaurant and eat. Put back a few beers. The topic of training never arises. The next morning I kill it at the pool.

8.14.07

This Might Work

I've been dreading this. With my race 11 days away, it's time for another mock tri, this one approximating race distanceÔÇö750 meters in the pool, 13.4 miles on the bike, and a three-mile run. During the swim, I alternate between freestyle and breaststroke, pacing myself. Eighteen minutes later, I've coasted through the longest swim of my life. Cake.

The ride consists of five 2.64-mile laps through town. I don't know how it's possible, but from every direction it seems I'm pedaling into a headwind. It takes 47 minutes, meaning I averaged just over 17 miles per hour. Elite triathletes ride about 50 percent faster. The transition from bike to run, even for the most seasoned Ironman vet, sucksÔÇödifferent muscles and rhythms, a new sort of battle with gravity. After only a few strides, I have a piercing pain under my kneecap, and my legs feel like wet sacks of sand. But I make it through. My total time is around 1:30, which would place me tenth in my age group, judging by last year's finishing times.

“Great,” says Brittany. She says this in the same tone that I used when my parents, after four years of VCR ownership, called to tell me they'd finally figured out how to record programs. I don't take umbrage. She's 20. Her possibilities are wide, expanding. But it's different for older guys, with faltering IT bands, trick knees, and slowing recovery time. Anything that can make us forget that, even for an hour and a half, feels like Christmas morning.

8.25.07

Race Day, Part 2 Oh, shit …

“Go!”

We're off. My hope for a smooth, unmolested swim ends five seconds in. I can't see. I'm getting kicked. I'm out of breath. I revert to the breaststroke and entertain thoughts that I'm not going to make it. But I carry on. How? Shame. The thought of the boat ride back, the stares. Hey, when I'm 300 meters out in the middle of a reservoir, I'll take whatever impetus I can get. Remarkably, though I feel shell-shocked, I exit the water 34th out of 42 in my division, men's 35ÔÇô39.

The bike is a welcome relief, but I take Scott Ford's “recovery time” advice perhaps a bit too far. My split is 48:07, and I drop a spot in the standings.

The run is a surpriseÔÇöno pain. So I decide to empty the tank and hold an 8:01-per-mile pace. My split is 11th fastest in my division, and my 1:42:55 total time places me 30th among my peers and 175th out of 293 overall.

As I cross the finish line, I can't hear the crowds. All I know are my burning legs, my throbbing head, lungs clawing for air. Then I hear a lone voice. “Tim Struby!” the announcer yells. “From New York, New York!”

8.27.07

Bring It On

Two days later I'm back training. Just because I've finished with the race doesn't mean I'm finished. I'm still only nine weeks in.

And guess what? I'm having more fun than ever. Without the pressure of an impending race, I'm trying different swimming drills, exploring new mountain-bike trails, and testing various stride lengths for my runs.

At the end of my 12 weeks, my running splits dip below eight minutes, my swim sessions go longer than ever, and my final ride delivers my fastest time yetÔÇö21.15 miles in 1:03:24.

I'm in the best shape of my life and primed for my next event. Whatever it might be.

The Coach

Utah Jazz strength-and-conditioning coach Mark McKown

My immediate goal was a triathlon, but what I was really after was all-around fitness that would keep me healthy and productive regardless of sport or setting. To this end, I enlisted the help of Utah Jazz strength-and-conditioning coach Mark McKown, 51, who holds a master's in sports science from the United States Sports Academy, in Daphne, Alabama, and has trained everyone from NBA power forwards to featherweight NCAA cross-country runners.

“I feel that most folks who participate in triathlons are in the midst of a self-competition,” he told me during our first meeting. “They have a primary goal of self-improvementÔÇöemotional as well as physical. So I designed the training approach with the idea of helping you prepare for a triathlon while developing a body that will meet other physical demandsÔÇörunning to catch the subway, climbing the stairs in your apartment building, boxing, bullfighting.”

While McKown, author of , can easily riff on everything from fartlek workouts to creatine-phosphate systems, it is his ability to motivate that makes him special. Six foot seven with a shaved, ruddy head and South Carolina twang, he reminds me slightly of Slim Pickens. He quotes from Mark Twain and Homer Simpson, tells stories about Milo of Kroton (the legendary Greek wrestler) and his own 17-year-old, football-playing son. Whatever it takes. (A night of beer and pizza got me back on track.) “As a trainer, you have to understand conditioning, the athletic demands of sport, and the athlete's mind,” says McKown. “Then it's up to the athlete's own confidence, competitive nature, and genetic programmingÔÇömixed with a healthy fear of failure.”

The Diet

Registered dietitian Beth Wolfgram on quality and timing of meals

“Two of the most important aspects of an athlete's diet are the quality of the food and the timing of the meals,” says Beth Wolfgram, a registered dietitian with the University of Utah who helped retool my approach to eating.

The quality is easy. Rely on things like homemade pasta sauces (tomatoes, garlic, and extra-virgin olive oil), omelets, stir-fry, bean-and-rice burritos, broiled fish, saut├ęed chicken, and colorful salads. But with jobs, families, and training schedules, the timing can require major adjustments. “The two most common problems that arise,” says Wolfgram, “are not eating often enough and top-loadingÔÇöskipping meals during the day, then gorging at night.”

First rule? Sometimes you have to force yourself to eat. You might not feel hungry before a morning run, but your body needs the fuel, especially for a long workout. Otherwise, you won't be able to train hard enough to get the full benefit. Even more important is the recovery meal, which is absolutely vital if you plan on training hard again within the next 24 hours. “For every kilogram of body weight [pounds divided by 2.2], you'll want about 1.2 grams of carbs and 0.1 gram of protein,” says Andrea Chernus, a New YorkÔÇôbased dietitian and exercise physiologist. So, for a 160-pound guy, a good recovery meal should deliver about 87 grams of carbs and seven grams of protein. Three ounces of cereal with fruit and milk would do the trick. Get it all down within what nutritionists call the “golden hour”ÔÇöthe 60-minute period following a workout, when the body's ability to absorb nutrients peaks.

The Strength: Upper Body

Hitting the Weights

Proper strength training improves body control, enhances speed, and helps increase resistance to injury. Combined with aerobic activity, two to three strength sessions a week is enough to deliver the benefits. Choose weights that just enable you to complete the prescribed numbers of sets and repsÔÇöheavy enough that you're not working, but not so heavy that your form falls apart. Do all the prescribed sets of each exercise before moving on to the next. Approximate time for full workout: 60 minutes.

Upper Body

Do two sets of 20 reps for each exercise. Go in the order listed, and complete each exercise before moving on to the next. Rest 30 seconds between sets.

Dumbbell Bench

Lie on your back on a bench, with a dumbbell in each hand. Without arching your back, press the dumbbells up, keeping them aligned with your pecs. Lower slowly.

Dumbbell Incline Bench

This is performed the same way as the dumbbell bench, but with the bench at an angle of about 30 degrees and the dumbbells aligned with top of pecs/front of shoulders while in motion.

Lat Pulls

Sit at a cable pull-down machine and place your hands as far apart on the bar as comfortably possible. Pull the bar down slowly, keeping your back straight. Touch the bar to your chest on front pulls and your neck on rear pulls. Do two sets on each side.

Shoulder Fly

Sit on a stability ball or stand with your feet shoulder width apart, a dumbbell at each side. With elbows slightly bent and your back straight, raise the dumbbells out away from your body until they are even with your shoulders.

Triceps Push-downs

Sit at a cable pull-down machine and place your hands shoulder width apart on a straight bar. Your hands should be at chest level, with your elbows bent and tucked in at your sides. Slowly bring the bar down until your arms are fully extended. Do not lean forward or swing your arms.

Dumbbell Biceps Curls

Alternate reps between arms. Do not swing your arms or your back or rock on your feet.

Cable Row

Sit at a cable row machine at a distance that forces you to bend forward slightly to reach the bar, with your knees slightly bent. Grab the bar at shoulder width and pull toward your waist. Once your back is perpendicular to the floor, continue pulling with your arms, shoulders, and back muscles, until the bar touches your abdomen. Concentrate on bringing your shoulder blades together.

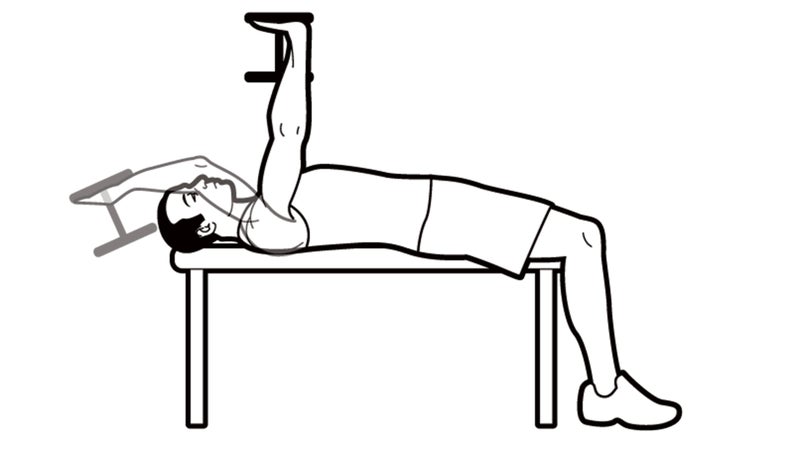

Dumbbell Pull-over

Lie on your back on a bench, with your head hanging just off the end. Grasp a dumbbell by placing both hands under the plate at one end, and hold it directly above your chest. Reach the dumbbell back over your head until your upper arms are parallel to the floor.

Lower Body

Two sets of 20 reps for each exercise. Complete each exercise before moving on to the next. Rest 30 seconds between sets.

Romanian Dead Lifts

Stand with feet together, knees slightly bent, arms hanging with the dumbbells touching your thighs. Keeping your back straight, slowly lean forward. The dumbbells should travel down beside your legs. Return to standing and repeat.

Lunge

Grasp two dumbbells at your sides and stand with feet shoulder width apart. Take an exaggerated step forward and bend your front knee until your thigh is parallel to the floor. Your back knee should be almost touching the floor. Push off forcefully with your front leg to return to standing. Do two sets for each leg.

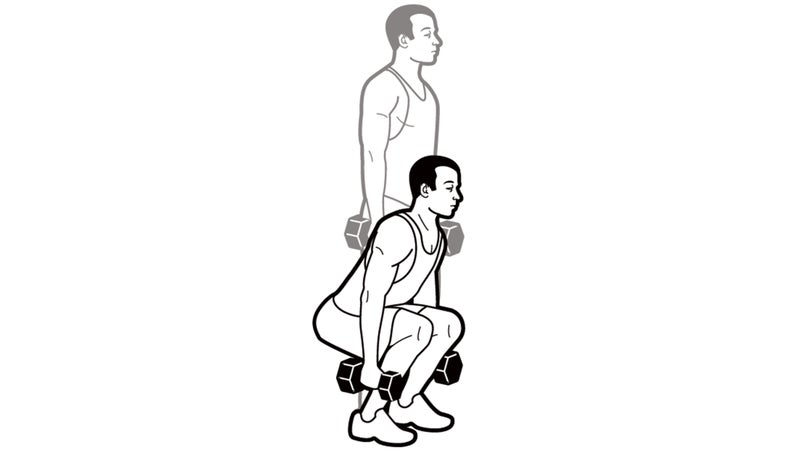

Sumo Squat

Stand with feet pointed out, knees slightly bent, and feet far apart. Hold a dumbbell by the end and squat down until it touches the floor, then stand back up.

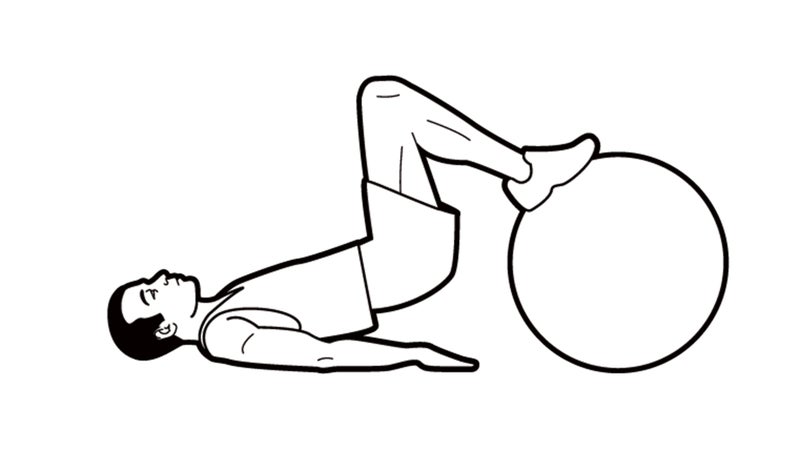

Stability Ball Hamstring Curl

Lie on your back with your heels on a stability ball. Arch your hips up so that your body is straight and only your head and shoulders are on the floor. Press down on the ball with your heels and roll the ball toward you until your knees are at a 90-degree angle, then roll it back to the start position.

Heel Raises

Grasp a dumbbell in each hand and stand on a step or platform, with the balls of your feet on the platform and your heels hanging off. Lock your legs and let your heels drop until you feel a good stretch in your calves, then rise up as far as you can on your toes.

Body Control

One set of 20 reps for each exercise, unless otherwise noted. Complete each exercise before moving on to the next. Rest 30 seconds between sets.

Stability Ball Bridge

Sit on a ball with your feet hip width apart. Walk your feet forward and keep your hips up, while leaning backwards to keep your upper body in contact with the ball. Continue until your knees are at a 90-degree angle, only your upper back and head are touching the ball, and your body, from knees to shoulders, is parallel to the floor. Hold for 60 seconds. Do two of these.

Push-up

Place your hands on the floor, shoulder width apart. Straighten your body to plank position and lower slowly. Stop one inch from the floor, hold for a beat, and push back up slowly until your arms are fully extended.

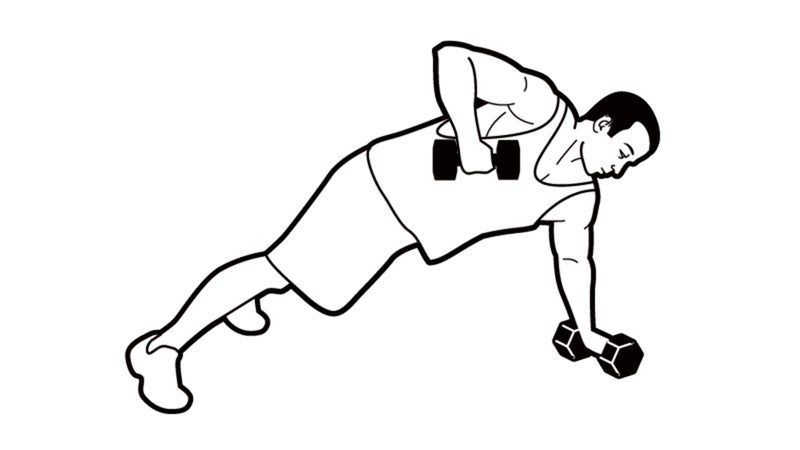

Push-up Row

Get into a push-up position, but with your hands on dumbbells instead of the floor. As you push off, explode up and bring one dumbbell up to your side. Immediately repeat on the other side. A set of 20 will alternate to each side 10 times.

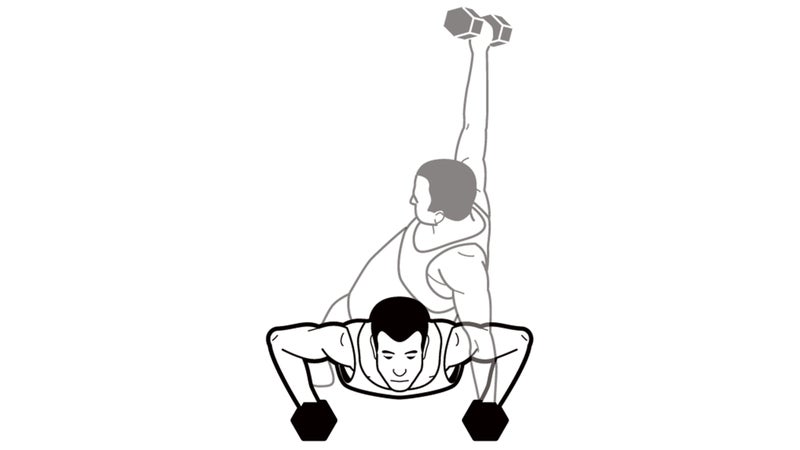

Push-up with Rotation

This is similar to the push-up row but performed with lighter dumbbellsÔÇöor no weights at all if the exercise is too hard. As you come out of the arm-extension phase of the push-up, rotate your trunk and extend one arm toward the ceiling. Alternate reps between sides.

The Stretches

Don't Flex in Vain

We've all seen the research suggesting that stretching before exercise doesn't prevent injury and may actually promote it. So why bother stretching at all? Because done correctlyÔÇöafter exercising or at least after a warm-up runÔÇöit increases stride, improves muscle elasticity, and, yes, reduces the risk of injury. Try to do it daily. But if you stretch cold, you're on your own. Approximate time: 10 minutes.

10 reps for each leg:

Straight-Leg Hamstring

Bent-Knee Hamstring

Straight-Leg Groin

Quad Stretch

Figure-Four

Standing Calf

The Core

Unstuck in the middle

Nearly every athletic movement originates in the core or has to transfer through it. Strength here delivers coordination, grace, and resistance to injury and back pain. Use slow, steady movements, focusing on form. Do the following routine circuit style, one exercise after the other, with no rest between sets. Do three sets of 20 reps each for crunches, pelvic tilts, and knee touches, one 15-rep set for swimmers, and one 30-second hold for each plank. Work through the list three times. As your conditioning improves, increase the reps by five and the planks by five seconds. Approximate time: 10 minutes.

Crunches

Lie flat on the floor with your legs bent and feet flat. Clasp your hands behind your head and roll forward from the waist, bringing your head toward your knees but keeping your lower back on the floor. To keep your abs engaged, concentrate on pressing your belly button toward the floor.

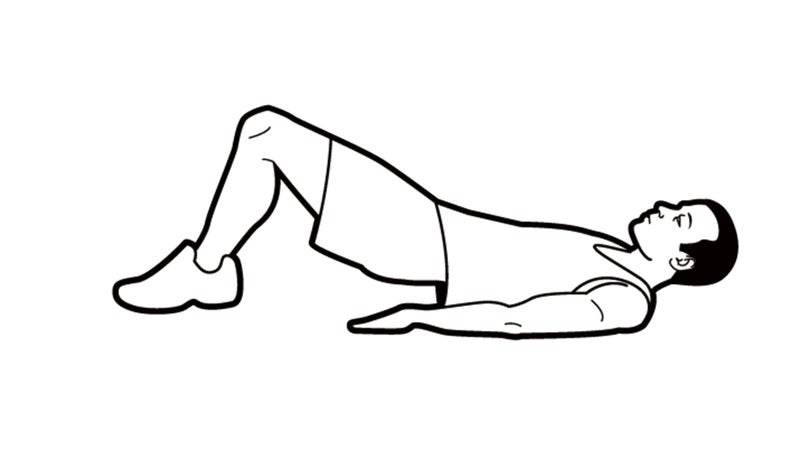

Pelvic Tilts

Start as if doing crunches, but place your arms on the floor, parallel to your torso. Press down with your hands, feet, and shoulders while lifting your hips up until your body is in a straight line from knees to shoulders.

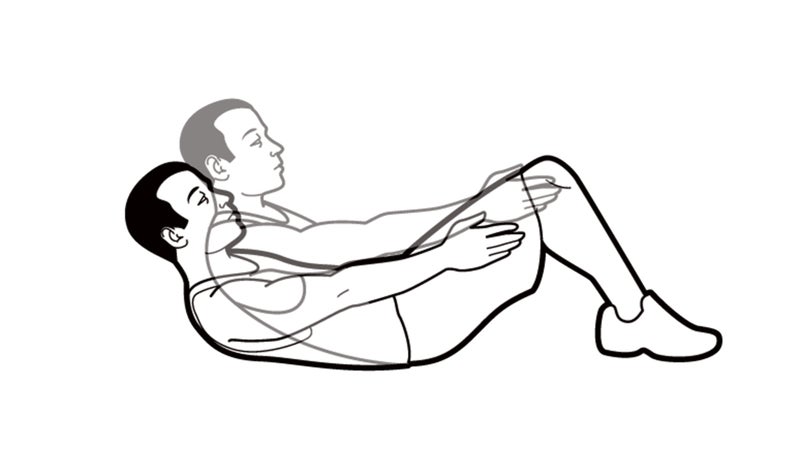

Knee Touches

Start as if doing crunches, but place your hands on your thighs, so that your shoulders are off the floor. Slide your hands along your thighs by rolling your upper body forward, until your hands touch your knees. Don't let your shoulders touch the floor between reps.

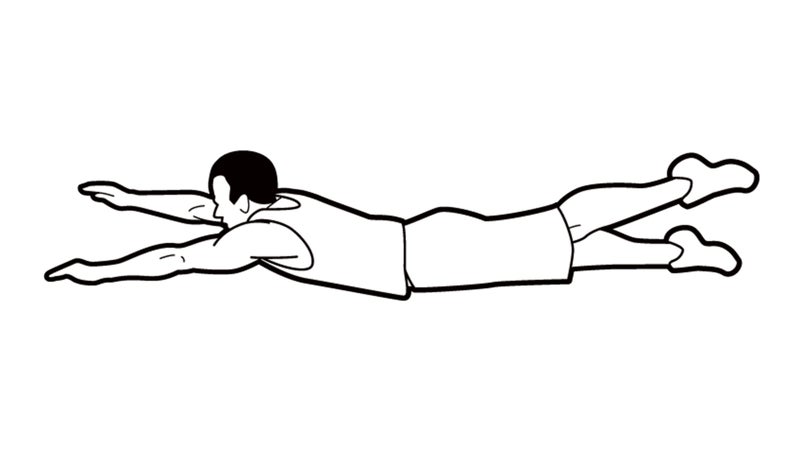

Swimmers

Lie facedown and extend your hands in front of your headÔÇöthink Superman pose. Arch your back so that your legs, chest, and arms are all off the floor. From this position, raise your left arm and your right leg simultaneously, as high as you can. Lower them and do the same with the opposite extremities.

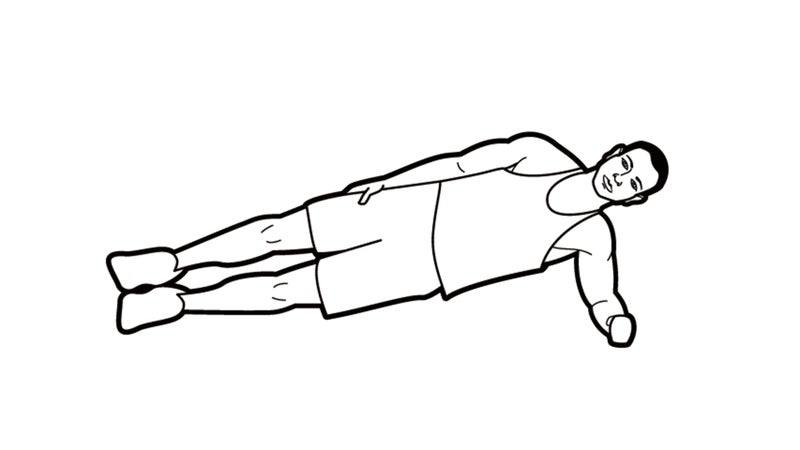

Side Plank

Get on your side with your elbow below your shoulder, forearm perpendicular to your body. Place your top foot on or just in front of the other and keep your body completely straight. Lift your upper body so that only your feet and forearm are touching the floor, and hold. Do 30 seconds on each side.

Prone Plank

Place your forearms on the floor, parallel to your torso and with your elbows under your chest. Lift into plank positionÔÇöbody completely straight and only your feet and forearms touching the floor. Keep your head aligned by looking down at the floor. Hold for 30 seconds.

The Plan

It looks daunting, but McKownÔÇÖs 12-week multisport program works even for people who have jobs. The average session lasts between one and two hours, with the longestÔÇöabout three hoursÔÇöfalling on Saturday.

Get a printable version of McKown's plan here.