The trickiest part of strength training, for most endurance athletes, is getting started. There are plenty of good reasons to do it, both for health and for performance. But there’s an important wrinkle that doesn’t get much attention: when should you stop?

The practice of tapering—a short-term reduction of training before an important competition—is common practice. A big concluded that the best approach is a two-week period during which you gradually reduce training volume by 40 to 60 percent without altering the frequency or intensity of your workouts. More recently, researchers have suggested that a “,” avoiding stressful or mentally fatiguing activities before a big race, could be useful. But how and when do you taper your strength training routine?

in the journal Sports offers a little bit of data, from a team led by Nicolas Berryman of the Université du Québec á Montréal. It’s a belated follow-up to that looked at the effects of strength training on running economy, which is a measure of how much energy you require to sustain a given pace. That study, like many similar ones, found that adding certain types of strength training did indeed make runners more efficient. The new study reanalyzes data on a subset of the original subjects who underwent further testing four weeks after they’d stopped the strength training intervention.

It’s worth recapping a few details of the original study, which involved just one training session a week for eight weeks. One group did a “dynamic weight training” routine of concentric semi-squats using a squat rack, exploding upward as quickly as possible. The other group did plyometric training, performing drop jumps by stepping down from a box and immediately bouncing as high as possible. The box height was 20, 40, or 60 centimeters, chosen based on what height produced the highest jump for each subject. In both groups, they started the first week with three sets of eight repetitions, with three minutes of rest between sets, and eventually progressed to a maximum of six sets.

In the original study, the plyometric group improved their running economy by an average of seven percent, the dynamic weight training group improved by four percent, and a control group that didn’t do either saw no change in their running economy. That’s consistent with other studies, which have found a range of two to eight percent improvement in running economy from various forms of strength training. For context, recall that Nike’s Vaporfly 4% shoes upended the running world because they offered an average running economy improvement of four percent. Strength training is legit, at least among the recreational athletes in this study.

So what happens four weeks after the subjects stop their strength training? Only eight subjects completed this follow-up (four from the plyometric group, four from the dynamic group), so they’re all lumped together for this analysis. These subjects maintained their newly improved running economy, and lowered their 3,000-meter race time even further.

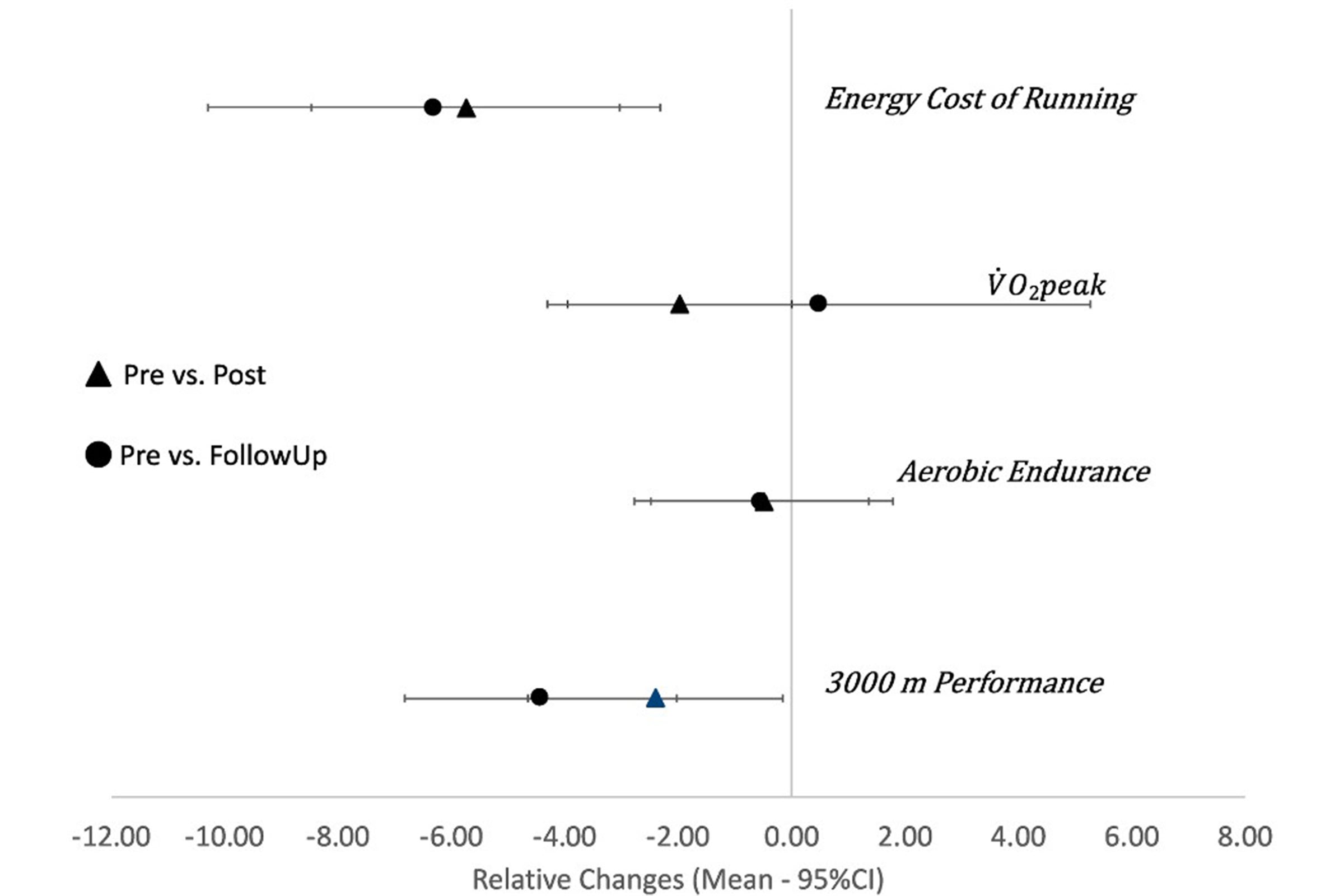

Here’s a graph of some of the key outcomes. The triangles show changes from baseline after eight weeks of strength training; the circles show changes from baseline after the additional four weeks with no strength training.

Running economy (shown here as “energy cost of running”) was essentially unchanged by the four-week taper. Aerobic capacity (shown here as “VO2peak,” which is basically the same as VO2 max) actually seemed to regress a bit during the taper, which is surprising and may just be a fluke. In contrast, 3,000-meter race performance ends up 2.4 percent better after strength training and 4.4 percent better after the strength training taper—which is precisely the kind of extra bump you hope to get from a taper.

(We’ll ignore “aerobic endurance” in the graph above. It’s defined as the ratio of peak treadmill speed in the VO2 max test to 3,000-meter race speed. I’m not clear what its significance is, but it didn’t change during the taper anyway.)

The authors go out of their way to emphasize all the caveats here, particularly the small sample size of eight subjects. We also don’t really know how things were changing during the four-week taper. Maybe the best performance of all was actually one or two weeks after the cessation of strength training. Still, the results suggest that the running economy boost you get from strength training—which is widely considered to be the main performance benefit for endurance athletes—sticks around for at least four weeks without any additional strength training. If nothing else, this suggests you can err on the side of caution in backing off your strength routine fairly early.

The question that’s left hanging is whether the extra boost in 3,000-meter performance after the taper (despite running economy staying the same and VO2 max getting worse) is just a statistical quirk, or whether it’s something real. There’s simply not enough data here to draw conclusions, but there are that there might be an “overshoot” effect that supercharges your fast-twitch muscle fibers a week or two after you stop your strength training routine. That’s fodder for future research—but even without an overshoot effect, these results add support to the idea that you can and probably should taper your strength training at least a week before a big race.

For more Sweat Science, join me on and , sign up for the , and check out my book .