It’s the greatest performance hack of them all, and all it costs is a third of your time on this planet, give or take an hour or two. I’m talking about sleep, which over the past few years has become even more of an obsession among athletes and other strivers. Forget : the mark of a great athlete these days is “high sleepability,” which is the skill of falling asleep quickly and easily whenever the opportunity arises, even if you’re not sleep deprived.

With that noble goal in mind, I bring you , published in this month’s issue of Sports Medicine, on the links between sleep and sports injuries, a topic I’ve written about a of times previously. The overall conclusion, on the basis of 12 prospective studies, is that—oh wait… apparently there’s “insufficient evidence” to draw a link between poor sleep and injuries in most of the populations studied. This non-finding is a bit surprising, and is worth digging into a little more deeply because of what it tells us about the dangers of getting too enthusiastic about seemingly obvious performance aids.

First disclaimer: I’m a big fan of sleep. I make a fetish of trying to spend enough hours in bed that I virtually never have to wake up to an alarm clock. I mention this because I suspect a lot of the recent sleep boosterism comes from people like me who are already inclined to get eight-plus hours a night, and are eager to embrace any evidence that suggests they’re doing the right thing. When I read a paper about some supposed new performance-boosting supplement, my antennae are on high alert for any flaws in research design or conflicts of interest. For something like sleep, I’m likely to be less critical. And I’m not the only one.

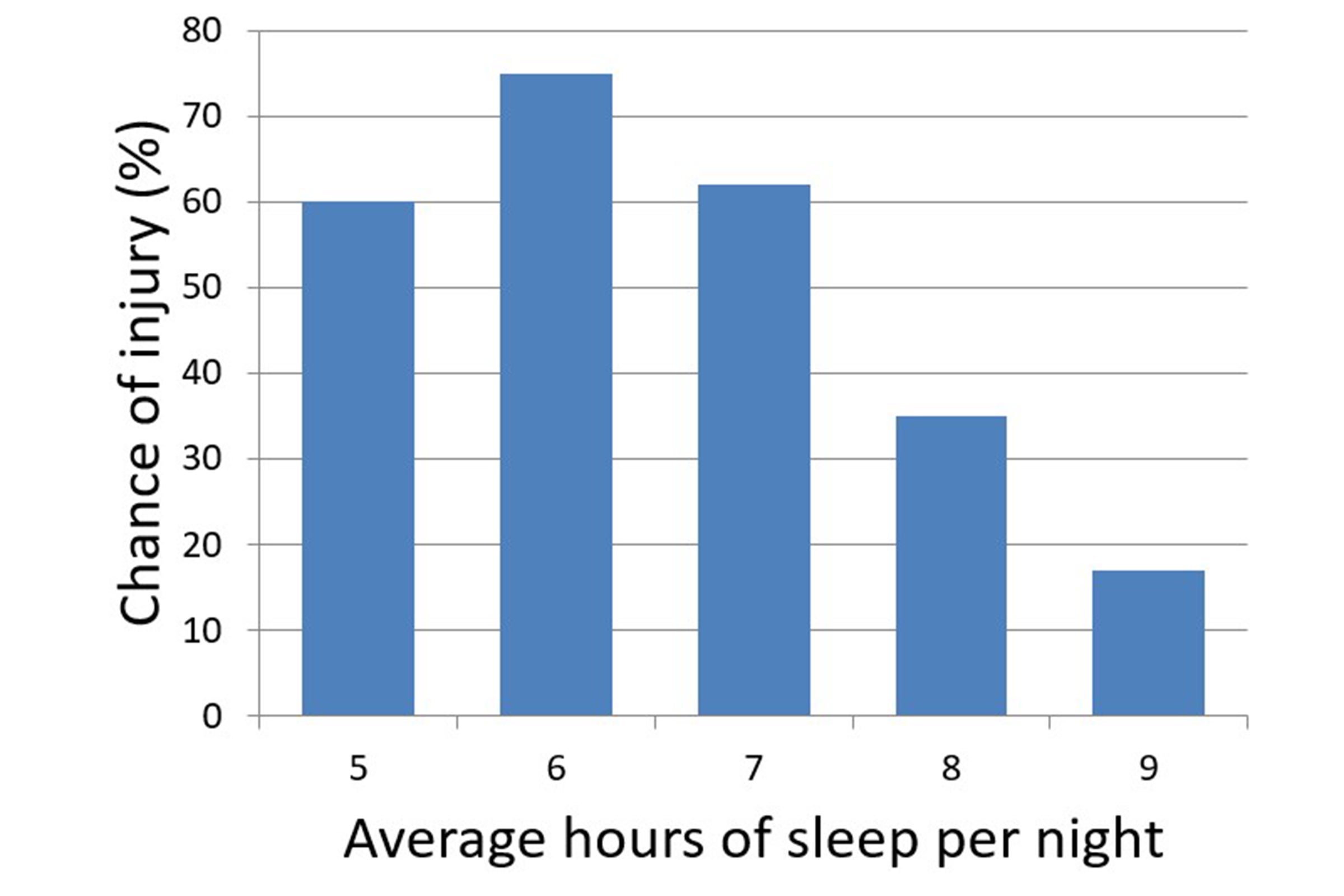

Back in 2015, a study in the Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics that parsed injury data from 112 athletes at a high-end Los Angeles high school. I included this graph showing an apparent relationship between injury risk and self-reported hours of sleep per night:

The association looks pretty clear here: athletes who got eight or more hours of sleep a night were much less likely to get injured. But does lack of sleep actually cause injuries? That’s trickier to say.

In the new Sports Medicine review, which is authored by a group at Towson University led by Devon Dobrosielski, a few different causal mechanisms are discussed. Sleep deprivation has been shown to suppress testosterone and growth hormone production and enhance cortisol levels, which could weaken muscles and leave you more susceptible to injury. Sleepiness can also slow your reaction times and lead to more attention lapses, which could raise your risk of a turned ankle or a puck in the face. But there are also plenty of non-causal possibilities: it could simply be that athletes who obey the “lights out at 10 P.M.” rule are also more likely to conscientiously avoid risky plays and sudden increases in training volume. Or a separate factor like overtraining might both disrupt sleep and raise injury risk.

I’ve been especially interested in this topic because that L.A. high school study made a controversial appearance in sleep scientist Matthew Walker’s 2017 bestseller . He even put the same graph in his book—with one crucial difference. , he left out the bar for five hours of sleep, making it look like there was a steady and inexorable rise in injury risk with fewer hours of sleep. (Walker has reportedly for subsequent editions of the book.)

There’s an interesting discussion to be had here about the “right” level of simplification. Effective science communication always involves pruning out extraneous details, and that pruning process is inherently subjective. You could argue that knowing what to leave out without distorting the message is the key skill in science journalism. And to be clear, I think Walker got that balance wrong in his original graph. But I don’t think it’s necessarily because he’s in the pocket of Big Sleep or anything nefarious like that. Instead, it looks more to me like an example of what I was talking about above: our tendency to embrace positive sleep research uncritically, because it seems so natural and harmless and, in some sense, morally right: if we’re good boys and girls and go to bed on time, the injury fairy will leave us alone.

But back to Dobrosielski’s review: he and his colleagues found 12 studies that met their inclusion standards. All dealt with adult athletes, and all were prospective, meaning that they had some initial assessment of sleep quantity or duration followed by a period during which they monitored injuries. Six of the studies didn’t find any significant association between sleep and injuries; the other six did, but the studies were so different that there weren’t any general patterns about what types of injuries or athletes or sleep patterns were most important.

It’s worth noting that looked at the evidence for adolescents instead of adult athletes. In that study, they concluded that adolescents who were chronically short of sleep—a definition that varied between studies, but typically meant getting less than eight hours a night—were 58 percent more likely to suffer a sports injury. That estimate, though, was based on just three studies, and still doesn’t sort out the difference between correlation and causation.

In the end, I continue to believe that sleep is good for us, and that people who insist they only “need” five or six hours a night are kidding themselves. But the truth, as Canadian Olympic team sleep scientist Charles Samuels told me a couple of years ago, is that there really isn’t that much evidence to back up these assumptions. The link between sleep time and injury risk, in particular, looks increasingly shaky to me based on the new review. In this age of relentless self-optimization, I can’t help thinking of one of Samuels’ other nuggets of wisdom: there are no bonus points for being a better-than-normal sleeper. Time in bed is valuable, but it’s not a magical panacea. If you miss your bedtime now and then, don’t lose any sleep over it.

Hat tip to Chris Yates for additional research. For more Sweat Science, join me on and , sign up for the , and check out my book .