The question at the heart of a lot of running science journalism is the same one that animates fawning celebrity profiles: “What is it that makes you so gosh darn wonderful?” To be fair, it’s a trickier question than it might seem at first glance. Millions of people swear by various forms of endurance exercise, despite the fact that it’s, well, hard. It’s reasonable to wonder what it is, exactly, that we get out of running—and how we can get more.

The latest mystery ingredient to catch scientists’ attention is oxytocin, the hormone associated with social bonding and an eclectic mix of other functions in the brain and body. We’ve long associated the feeling of runner’s high with endorphins, though research has also implicated and , and other lines of research have linked running’s mood-boosting powers to elevated and its cognitive benefits to . And that’s just a partial list. Whether oxytocin is yet another beneficial brain chemical whose levels are boosted by a good workout has been a subject of debate for many decades, but a handful of recent studies is bolstering the claim that it is. It’s clearly not the whole story of what makes running good, but the findings add a new wrinkle to our understanding of how running affects health and wellbeing.

First up is , from researchers in Iran, that tests two linked ideas: that exercises boosts oxytocin levels, and that these elevated oxytocin levels are responsible for exercise’s antidepressant effects. Mice were given eight weeks of swimming training, starting with ten minutes per day and progressing to 30 minutes per day, five days a week. Before and after the training period, they completed a series of tests that assessed social behavior and levels of depression-like symptoms. As expected, the swim-trained mice were more sociable and displayed less anhedonia (a lack of interest in or pleasure from life’s experiences) compared to the control group, which just hung out in empty swimming tanks with no water while the others were exercising.

Tests also showed that oxytocin levels were elevated in both the brains and bloodstream of the exercised mice. But how do you know if the oxytocin caused the behavioral changes? The researchers administered an oxytocin antagonist, which blocks the effects of oxytocin in the brain. That seemed to wipe out the observed social and antidepressant benefits of all that training.

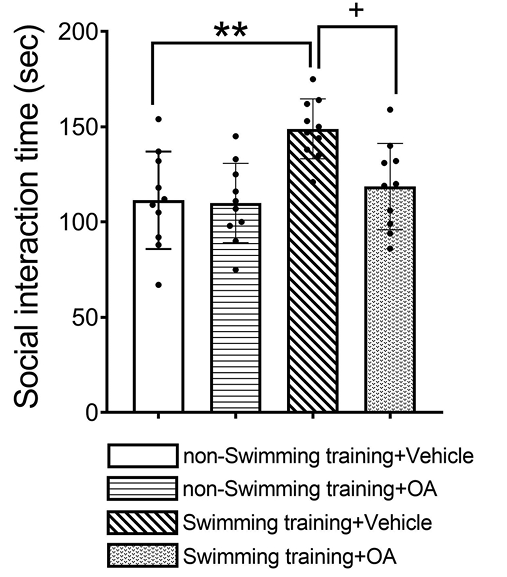

Here’s a sample of the data, showing how long the mice spent interacting with other mice in the test of social behavior. The first bar is non-exercised mice who got a placebo; the second is non-exercised mice who got the oxytocin blocker; the third exercised mice who got a placebo; the fourth is exercised mice who got the oxytocin blocker:

One of these bars is not like the others: the mice who swam were more social, unless the effects of oxytocin were blocked.

I know, I know—that’s in mice. What about humans? The picture is much less clear, in part because of the limits of what we’re able to measure in the brains of living humans. , published in Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, makes a heroic effort to clear up some of the confusion. Researchers in Japan and Denmark put volunteers through a pair of high-intensity interval workouts, each consisting of 4 x 4:00 of hard cycling with 3:00 of easy recovery. The entire workout was repeated twice with an hour break.

They did all this with catheters inserted in their brachial artery (in the arm) and jugular vein, which carries blood from the brain. The goal: figure out how much oxytocin is in the blood as it enters the brain, and how much is in the blood as it exits the brain, in order to determine whether levels in the brain are changing during exercise. You can see why these experiments are hard to do.

The results are a mix of surprises and non-surprises. The workouts increased oxytocin levels in the blood. But the increase was the same in the artery going into the brain and the vein coming out, which wasn’t what they expected. It may be that oxytocin production in the brain doesn’t increase; or that it increased so much that it raised levels in the entire body; or that blood from the hypothalamus (where most oxytocin is produced) drains from a different vein rather than the jugular. There are other places in the body where oxytocin can be produced, including the muscles and heart—indeed, published last month found oxytocin in human sweat, leading the researchers to suggest that it’s also produced in the skin during exercise.

Interestingly, the Japanese and Danish researchers seem most interested in the potential cardiovascular benefits of oxytocin, rather than mood benefits, since oxytocin has effects on blood pressure and circulation. And it has other purported powers: published earlier this month, to pick one more or less at random, found that oxytocin injections reduce periodontitis (severe gum inflammation) in rats, presumably due to its systemic anti-inflammatory effects.

It’s clear that the running-boosts-oxytocin-boosts-health axis has a lot of gaps that remain to be filled in, but the recent spate of results is intriguing. There are two ways we can react to this. One is to leap to the conclusion that oxytocin is “the secret” to some portion of the magic of exercise, so we should all start huffing oxytocin spray, tracking our oxytocin levels, and undergoing periodic oxytocin fasts. The other is to add oxytocin to the already exceedingly long list of mechanisms whereby exercise boosts our health, marvel at the complex interconnections between all these mechanisms, and conclude that no single pill or spray will ever replace the magic of a good run.

For more Sweat Science, join me on and , sign up for the , and check out my book .