In 1906, a Harvard professor named Arthur E. Kennelly, an electrical engineer who’d previously worked in Thomas Edison’s laboratory, his “Approximate Law of Fatigue in the Speeds of Racing Animals.” In an exhaustive treatise crammed with mathematical formulas and logarithmic graphs, Kennelly compared existing world records to what humans should, in theory, be able to run. Among his conclusions was that someone would eventually run a mile in the jaw-dropping time of 3 minutes and 58.1 seconds.

Kennelly was right, of course. It took almost half a century, but in 1954, a few weeks after Roger Bannister’s barrier-breaking sub-four-minute mile, John Landy ran 3:58.0. But Kennelly was also wrong, because progress didn’t stop there. The mile record kept falling with almost clockwork regularity until it reached 3:43.13 in 1999. And then, finally, it stopped. The 2000s were the first decade without a men’s mile record since modern records began being recorded a century ago. Unless something changes soon, the 2010s will be the second.

Earlier this week, the New York Times published a piece called “,” drawing on an published a few months ago in the journal Frontiers in Physiology, to make the case that athletic progress is grinding to a halt. Times in Olympic speedskating have stagnated since about 2005, and performances in others sports like track and field, swimming, cycling, skating, and weightlifting have been plateauing since the 1980s, the journal article argues.

Claims that the era of world records is over aren’t new. Since Kennelly’s time, numerous scientists and statisticians have developed models that calculated humanity’s “ultimate physical limits.” My 1991 edition of Tim Noakes’ Lore of Running has a whole chapter of models and predictions, ranging from the hopelessly optimistic (a 3:30 mile by 2028, according to a 1976 article in Scientific American) to the provably false (“People talk about the possibility of a two-hour marathon, but I think two hours five minutes would be a more realistic limit,” British marathon star Ron Hill predicted in 1981). But is it different this time? Are we really approaching the limits?

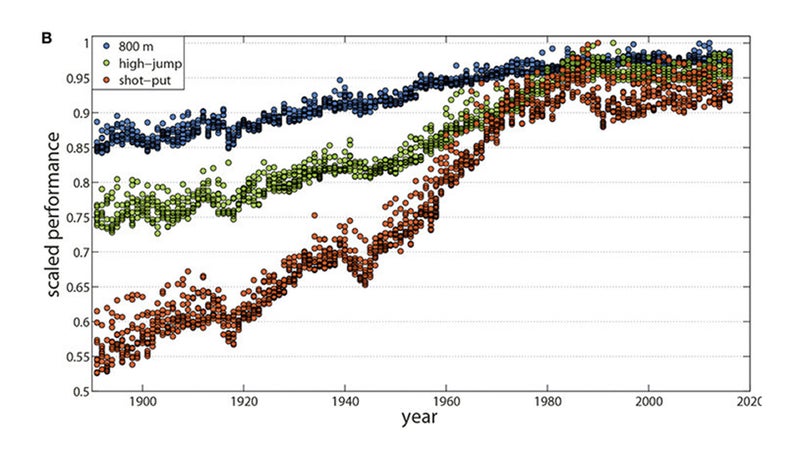

Here’s one of the key graphs from the Frontiers article, also reproduced in the Times. It shows the progression of the ten best performances in the world each year in the men’s 800-meter run, the high jump, and the shot put:

The relative lack of progress since the 1980s is pretty clear to see. But what does it actually mean? The Times piece has sparked some good discussion and elsewhere, and I think a few points are worth bearing in mind before we wistfully conclude that we’ll never see another world record.

Soft Records Are Mostly Gone

It’s pretty clear that records are getting rarer and happening by smaller margins in mature sports like track and field. In some of the early attempts at record prediction back in the 1950s and 1960s, statisticians used “linear models”—that is, they assumed the records would continue progressing indefinitely at roughly the same pace they had in the past. That’s no longer a reasonable assumption. Progress is slowing, and the low-hanging fruit is gone.

Of course, many sports are far younger than track and field. Who’s to say we’re anywhere near the limits of big-air snowboarding? And in judged sports, how would we even measure those limits, anyway? As long as we keep coming up with new sports, we’ll have plenty of firsts to celebrate.

Progress Is (Sometimes) an Illusion Anyway

A a few years ago recruited top athletes to race against virtual versions of long-ago record holders—wearing the old-fashioned equipment. Canadian sprint star Andre De Grasse managed an 11.0-second 100 meters in leather shoes and a dirt track like the ones Jesse Owens used to run 10.2 seconds. World record holder Paul Biedermann lost an all-skimpy-Speedo 200-meter freestyle race to virtual Mark Spitz. Science journalist David Epstein made a similar point in a few years ago, suggesting that Owens on a modern track would have stayed within a stride of Usain Bolt. So how much of the supposed progress of years past represents improvements in the intrinsic capabilities of the athletes, rather than simply better equipment?

It’s tempting to dismiss the leaps that are obviously caused by technological changes—fiberglass poles for pole vaulters, carbon-fiber shells for rowers, compression suits for swimmers—as aberrations that distort the “true” pace of human improvement. Same goes for the performance-enhancing drugs whose influence waxes and wanes as new drugs and new tests emerge. But when you look at graphs like the one above, those factors are baked into the picture. We had rapid progress in the past because the rules and implements of the game changed; if future progress comes thanks to technology, that will be no different.

As They Say, It’s Tough to Make Predictions, Especially About the Future

What sort of technological change might enable humans to go faster, higher, and stronger? Well, if we knew, we would be doing it already. One of the storylines I’ve been following for a few years is the use of electric stimulation. As I wrote a few months ago, there’s growing evidence that brain stimulation can alter how your brain perceives physical effort, allowing you to push harder for longer. There are already athletes in Pyeongchang using a form of electric brain stimulation, including U.S. Nordic combined athletes .

Will manipulating the brain allow athletes to tap into deeper physical reserves than ever before and enable the march of world record progress to continue? I’d say the odds are against it at this point, but this is the sort of unexpected development that could lead to new records while staying within current sports rules. Nike’s Breaking2 marathon last year offers another pathway, using things like better shoes and optimized drafting to enable faster marathons without any change in an athlete’s intrinsic capabilities. Nike’s race wasn’t record-eligible, but for better or worse, it won’t be hard to apply some of those tactics to record-eligible races. And there may be even more radical improvements if we start to required for extreme athletic performance.

We Haven’t Found All the Usains

Another key of part of the progress story is demographics. Runners today are way faster than they used to be, in part because the sport is no longer a niche pastime contested almost exclusively by well-off Europeans and Americans. But just because sports are global doesn’t mean we’re fully tapping into the potential that’s out there. As Epstein this week, “I can’t believe that Bolt is unique. If he’s born anywhere else, he isn’t a sprinter, so I’m convinced there are others, maybe a bunch.”

To put it another way, progress will follow money and cultural interest. Usain Bolt took arguably the most mature and widely contested event in history, the men’s 100-meter dash, and lowered the record by about 1.5 percent, from 9.72 to 9.58 seconds. And this was in 2008 and 2009, well into the supposed plateau period. Such breakthroughs are and will remain rare—but there’s no reason to think they won’t continue to occur.

We’re Not Horses

Finally, I think it’s worth considering a sport where performances really do appear to have plateaued: thoroughbred horse racing. According to of historical records, times in major horse races have mostly stagnated since the 1950s, while humans have continued to get faster. The Kentucky Derby record is still Secretariat’s 1:59.4 from 1973.

What’s the difference? There is “a psychological incentive for human athletes to not only win races but to win them in record-breaking times,” the authors of the analysis wrote. “The horse knows no such incentives.” If someone runs a 2:03:00 marathon, other runners know that a 2:02:59 is possible, and they’ll plan their training and racing accordingly. A horse can only run against his or her own competition on any given day.

When it comes down to it, that’s why I expect to see records continue to fall. They may become less common, and the margins may be smaller. And the focus on records may be, in some ways, a distraction from the more compelling story of head-to-head competition among humans rather than against the clock or the tape measure. But there’s another prediction quoted in Noakes’ book that has always stuck with me—one that left a deep enough impression that I actually included in my high school yearbook profile when I graduated. It’s from 1903: “The man who has made the mile record is W.G. George…His time was 4 minutes 12.75 seconds and the probability is that this record will never be beaten.” Let’s not make that mistake again.

My new book, , is now available! For more, join me on and , and sign up for the Sweat Science .