In 1995, Haile Gebrselassie was at the peak of his powers. The Ethiopian superstar was already the reigning world record holder over 5,000 meters and world champion over 10,000 meters. Then, , he sliced a massive nine seconds off the 10,000-meter world record, clocking a nearly incomprehensible time of 26:43.53. It was the kind of epochal, ��performance that you expect to last for a generation or more.

Two years later, Gebrselassie ran 26:31.32. And the year after that, he ran 26:22.75.

How do experienced runners who are already fast, fit, and well-trained beat their previous times? That’s the question tackled by in the International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, by University of Wisconsin-La Crosse researcher Carl Foster and his colleagues at VU-University-Amsterdam and several other institutions. While there are several obvious possibilities (e.g. getting fitter by training harder or smarter), Foster and his colleagues examine the role of pacing. With experience, do runners get better at optimizing how they spend their energy throughout a race?

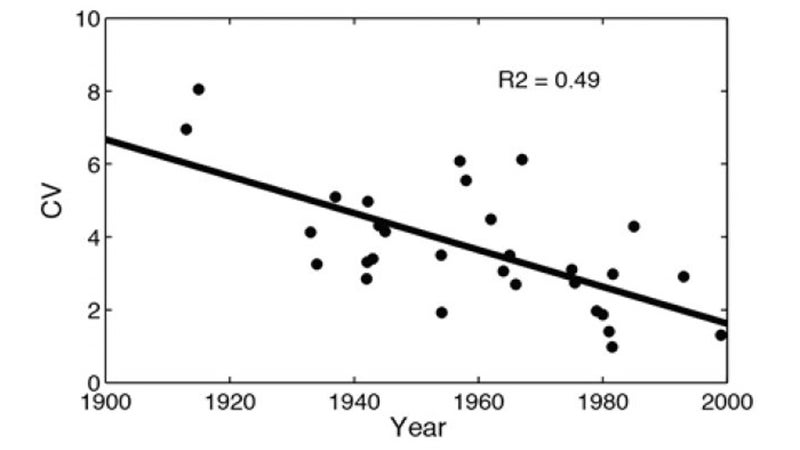

Back in 2014, some of the same researchers did of the progress of the �����’s and wo�����’s world mile records, digging into the lap times for records dating back more than a century. The pattern they found was a pronounced trend toward more evenly paced laps. For the �����’s records, the lap-to-lap variation of records in the early 1900s (expressed as a , which is the ratio of the standard deviation to the mean)��were around 7 percent. Over the next century, that variation steadily declined, approaching 1 percent for the most recent records.

Here’s a graph of how that coefficient of variation (CV, in percent) has declined in �����’s��mile world records over the years. (The wo�����’s record, which has only been officially tracked since the 1960s, doesn’t show a pronounced trend, with a typical variation of 2 to 3 percent. Sifan Hassan’s , by my back-of-the-envelope estimate, had a coefficient of variation of around 2 percent.)

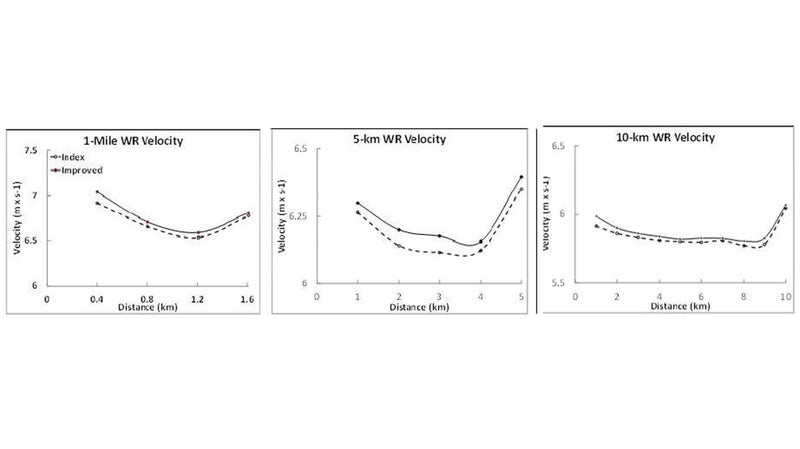

If you dig a little deeper into that analysis, you see that��mile world records (just like records in longer events) tend to follow : a fast first lap, followed by gradual slowing over the second and third laps, then a fast final lap. But over the past century, that U-shaped pattern has been flattening out. Relative to their overall average pace, modern record-setters still tend to have a fast first lap and slow third lap, but not quite as skewed as older record-setters. Over the decades, elite runners have “learned” to set a more even pace—and, the researchers suggest, this hints at prospects for further improvement if the coefficient of variation gets down to 1 percent.

The question in the new study is whether individual athletes like Gebrselassie follow a similar path when they improve their own world records. Is the difference between 26:43 and 26:22 due, at least in part, to Gebrselassie refining his pacing and producing a more even effort?

To find out, Foster and his colleagues once again turned to the past century of world records, looking at instances where runners bettered their own previous records over the mile, 5,000, and 10,000 meters. They found 22 runners who had improved their records, with a total of 35 pairs��of broken records. (Emil Zàtopek, for example, broke the 10,000-meter record five times.)

In this case, unlike the general historical trend, there was no evidence that runners had better pacing on their second world record��compared to their first. Here are the average before-and-after paces for those 35 world-record pairs:

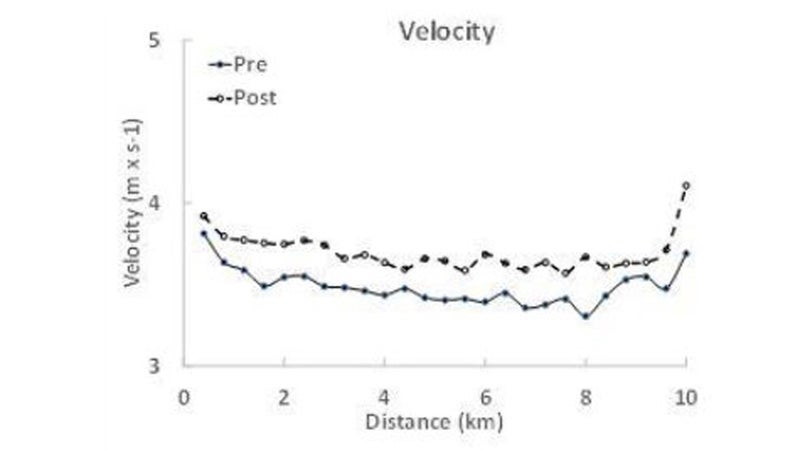

The researchers also performed a separate experiment in which they asked seven recreational runners to do a 10K time trial, then follow a more intense training program including three interval workouts a week, then return for another 10K time trial. As expected, the runners got faster after training harder, improving their times by an average of 6.8 percent. But there was no difference in the lap-to-lap pacing variation, which went from 4.4 to 4.8 percent. Both before and after, their pacing pattern looked strikingly similar to the pattern in the 10,000-meter world records:

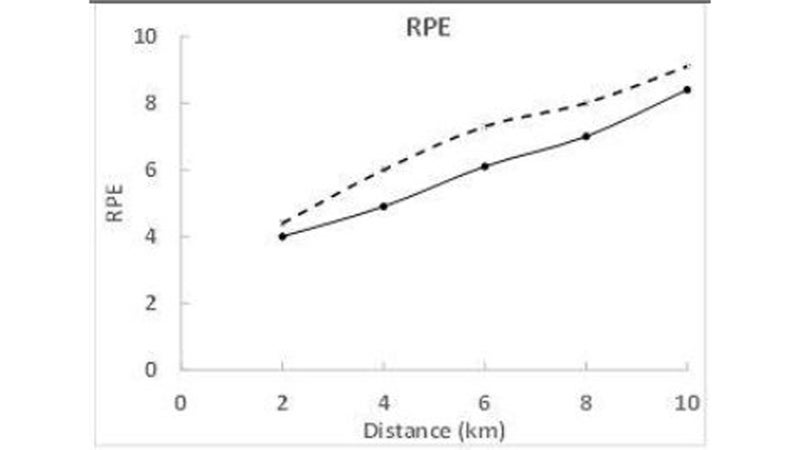

So how do runners get faster than their previous bests? For the recreational runners in the study, a big part of it was simply getting fitter by training harder. But that’s not the whole story: after training harder, they were also capable of pushing themselves a little harder. Here’s their self-reported rating of perceived exertion (RPE), on a scale of 0 to 10, throughout the two races,��showing that they felt they were pushing harder throughout the second race (the solid line is the first race, the dotted line the second race) :

I’ve always thought that learning to push yourself is an underappreciated part of the training process, beyond the purely physiological aspects. For the world-record setters, on the other hand, that’s a harder claim to make. The authors of the study argue that someone who is already capable of setting a world record is unlikely to make further significant gains in physiological fitness. They’re also unlikely to suddenly figure out how to try harder, and the new analysis suggests that they don’t improve their pacing either.

Instead, the typical improvement of 0.5 to 0.9 percent��looks a lot like the result of what the researchers call “contextual variables” (weather, track surface, other competitors and so on) or to a small amount of biological variability (sometimes you just feel really, really good). If that’s the case, then the message here isn’t that you need to master the subtle art of perfect pacing. It’s that you need to get out there and race. The more you roll the dice, the better your chances of hitting one of those elusive double-six days.��

My new book, , with a foreword by Malcolm Gladwell, is now available. For more, join me on and Facebook, and sign up for the Sweat Science .