You have no idea how tough [insert sport] is.

Whether we say it out loud or just repeat it to ourselves, many of us share this sentiment. As American novelist Mary McCarthy once said, “We are the hero of our own story.”

That said, some activities are legitimately harder than others, and in the realm of outdoor sports, a few are in a league of their own. Take rock climbing, for instance, which requires explosive upper-body strength, problem solving, and crux-time focus. Downhill mountain bikers regularly risk shattered bones, while open-water swimmers push themselves to the limit in unforgiving conditions. Nordic skiers force their bodies deep into oxygen debt, and ultrarunners—well, you get the idea.

But how can we quantify which one is actually the toughest? Here’s how: we chose five competitive sports that we feel are tough to learn, can be dangerous to perform, and require a high degree of skill and fitness.* We then looked at peer-reviewed research and compared calories burned per hour, the average number of injuries per 1,000 hours of an athlete’s activity, and fatality rates. Finally, we asked a panel of world-class athletes to weigh in on what makes their vocations so tough and to vote for the sport, besides their own, that they think is the hardest.

Before we make the call, let’s meet the contestants to answer the age-old debate: what is the hardest sport?

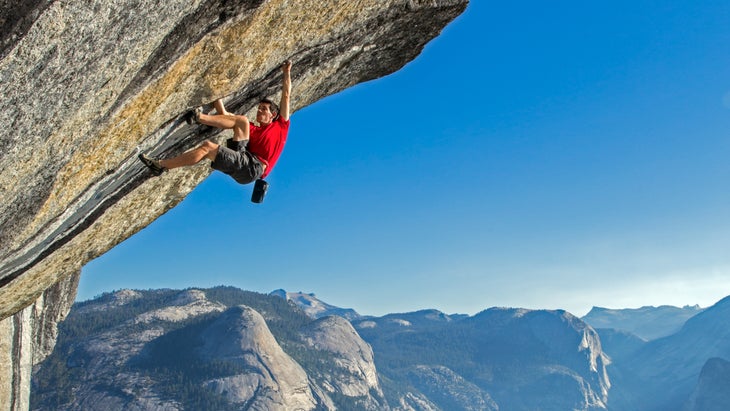

Rock Climbing

Calories burned per hour:Ěý818

Injury rate: 0.56 per 1,000 hours

Fatality rate: 145 per 1 million climbers

Experts: Steph Davis, Alex Honnold

How hard is it to learn?

“It’s pretty accessible because climbing gyms have become such a big thing,” says Steph Davis, the first woman to summit all seven peaks in the Fitz Roy Range in Patagonia and the second woman to free-climb El Capitan in one day. “You can just go to a gym and get taught how to start climbing.”

How do you train for it?

Most serious climbers spend time off the wall, tediously strengthening their upper body, core, and fingers. This type of training is in contrast to the sustained agony experienced by Nordic skiers and ultrarunners, but the explosive upper-body and grip-strength exercises, usually performed on a hangboard, are designed to hurt. A lot.

How often do you get injured?

Climbers regularly suffer rotator-cuff tears, tendonitis, trigger finger syndrome (where the finger locks in bent position), and a bouldering injury called subluxation, where a jarring hang causes the shoulder’s ball joint to detach from its socket. “I compression-thrashed two vertebrae in my back, and then I tore a ligament in my hand,” says Alex Honnold, the world-renowned big wall free-soloist and El Capitan speed-record holder. “I guess in 20 years it’s not too shocking to have a little bit of stuff happen.”

Why do you do it?

“The exposure, the position, being that little speck on the wall,” Honnold says.

Ultrarunning

Injury rate: 7.2 per 1,000 hours

Fatality rate: 2.5 per 1 million ultrarunners

Expert: Scott Jurek

How hard is it to learn?

Despite the fact that many of the toughest ultramarathons take more than 24 hours to complete, the physical act of running is easy to master. The hardest elements of ultrarunning—the things that separate the pros from the amateurs—are pace management, nutrition, hydration, and maintaining your sanity while running for a full day and night. “The hard thing for me is that at any time, I can stop and call it,” says Scott Jurek, seven-time winner of the Western States 100.

How do you train for it?

Training for an ultra is like taking on a second job: it often requires hundreds of hours of running over the course of many months. Shorter runs (under ten miles)Â are usually squeezed in during the week, while long runs (anywhere from 20 to 50)Â are reserved for the weekend.

“On Saturday, I might do something that has 10,000 to 15,000 feet of elevation gain at lactate-threshold pace—that type of workout lasts four to six hours,” Jurek says. “It’s followed up by a six-to-eight-hour long run [on Sunday].” Plus, he adds weight training two or three times a week with strength and stability exercises, such as one-legged squats, and lots of core work.

How often do you get injured?

While less susceptible to the catastrophic, bone-shattering injuries endured by, say, climbers and mountain bike riders, ultrarunners often fall victim to soft tissue and overuse issues, such as Achilles tendonitis, IT band syndrome, runner’s knee, and plantar fasciitis.

Why do you do it?

To suffer for 24 hours—to ignore the voice in your head telling you to quit and battle through the body’s progressively depleting energy systems—is not for the faint of heart or legs. Yet humans evolved to run, and for some, that primal instinct is motivation enough. “I love being able to cover vast distances in the woods and in the mountains,” Jurek says. “That ability to really explore my endurance capabilities. The human body was built for bipedal motion, and it’s a great way to travel out in the woods and the mountains and be unhindered.”

Downhill Mountain Biking

Calories per hour: 632

Injury rate: 43Â per 1,000 hours

Fatality rate:Â 11.2Â per 1 million mountain bikers

Expert: Rachel Atherton

How hard is it to learn?

“It’s like nothing else on earth,” says Rachel Atherton, who won all seven rounds of the 2016 Union Cycliste Internationale Downhill Mountain Bike World Cup in September. Traveling fast over loose singletrack and technical rock gardens takes guts, and there’s a big mental learning curve for those new to the sport. Not to mention, the cost of entry is steep: a full-suspension rig can easily cost as much as a lightly used Corolla.

How do you train for it?

Unlike the cross-country and enduro disciplines, downhill racers aren’t hitting the rollers for cardio conditioning. Besides spending time on the bike, dynamic lifts such as squats and deadlifts and muscle-searing upper-body exercises like weighted chin-ups are key to developing the strength required to muscle a 40-pound rig down a steep, rocky slope. “I train with my brothers Dan and Gee, who are also pro mountain bikers,” says Atherton. “I like to mix it up with yoga or stand-up paddleboarding or rock climbing to keep it fun. Apart from that, it’s vital to spend a lot of time on the bike.”

How often do you get injured?

The biggest danger of downhill mountain biking is—you guessed it—crashing. You have to contend with rocky surfaces and even the bike itself, which can turn into a sharp, heavy weapon when you go down. Atherton has learned to ride more carefully than when she was younger, but the years have taken their toll. “My shoulders are pretty beaten up,” she says. “I’ve had a nerve taken out of my leg and reinserted into my left shoulder. This has given me about 60 percent more muscle function than before the operation, which is a huge improvement.”

Why do you do it?

“Once I’m out of the start gate, riding my bike through all those roots and rocks and drops, it becomes like a dance or a meditation,” Atherton says. “And crossing that finish line, realizing that you’ve gone fastest, that you’ve conquered the mountain and won the day—there’s no feeling like it.”

Open-Water Swimming

Calories per hour: 957

Injury rate: 4 per 1,000 hours

Fatality rate:Â 9.1Â per 1 million open-water swimmers

Expert: Elizabeth Fry

How hard is it to learn?

“Swimming is 20 percent physical endurance and 80 percent mental endurance,” says Elizabeth Fry, one of four swimmers ever to have completed the Double Triple Crown—twice swimming the English Channel, Catalina Channel, and the Manhattan Island Marathon Swim. In addition to the tremendous exposure these athletes face—and the mental and physical challenges that exposure presents—Fry says the hardest parts of open-water swimming are dialing in your hourly feeding schedule, fitting in a time-intensive training regimen, and adhering to your safety protocol.

How do you train for it?

“During the week, a training session could be two hours, and on the weekends it’s closer to three,” Fry says. “And that’s a mix—it could be swimming; it could be a combo of swimming and yoga. We rely on big swims on the weekends.” It’s equally as tough on the mind, as swimmers must battle the extraneous and numerous variables of the ocean. “There’s nothing more challenging than to see your finish just minutes away after 12 hours of swimming through the dark, and to be told the tide has just changed and you will need to swim at least another four hours until the tide slacks,” Fry says. “It’s part of the sport.”

How often do you get injured?

Like runners, open-water swimmers suffer overuse injuries, but the biggest threat to athletes is, unsurprisingly, the water. Total exhaustion can mean drowning. To stay safe, crews talk to open-water swimmers like doctors would talk to patients with concussions, since they may be too focused on exerting themselves to consider their own well-being. “Your crew is counting your strokes, looking for changes, looking at the way you’re speaking, asking you questions that you should know the answer to,” Fry says.

Why do you do it?

Like Himalayan mountaineers, open-water swimmers often talk about the desire to test their minds and bodies over a long period of time in extreme exposure. “The longer it is, the better I am,” Fry says. “I do enjoy it.”

Nordic Skiing

Calories per hour: 952

Injury rate: 30 per 1,000 skiing hours

Fatality rate: 11 per 1 million Nordic skiers

Experts: Sophie Caldwell, Kikkan Randall

How hard is it to learn?

While technically it’s not as difficult to learn as downhill alpine skiing, Nordic skiing is almost unparalleled when it comes to required fitness. Traveling quickly, often uphill, using both your arms and legs, makes it a true full-body workout. In fact, the highest VO2 max ever recorded was in the lungs of Norwegian Nordic skier Bjorn Daehlie. “I truly believe that Nordic skiing is one of the most difficult sports in the world,” says Sophie Caldwell, 2014 U.S. Olympian in the freestyle sprint. “It requires so much strength and endurance from your entire body.”

How do you train for it?

Nordic skiers put in countless hours in the mountains training at lactate threshold. When there’s no snow, professional Nordic skiers like world champion Kikkan Randall get creative. “Roller skis allow you to simulate your ski motion on pavement,” Randall says. “You get a full-body workout like you do with cross-country skiing. We also do a lot of running in the mountains.” On a typical preseason training day, Randall says she “runs for a couple hours pretty much entirely uphill.”

How often do you get injured?

Similar to ultrarunning, the repetitive motion of Nordic skiing leads most often to overuse injuries, such as nagging soft tissue pains and stress fractures. Yet, nordic skiers have been known to forgo the excuses: “One of the many perks of our sport is that it’s full-body,” Randall says. “So if you injure your arm, you use your legs and vice versa.”

Why do you do it?

There’s something to be said for earning your tracks. And if you want to get in shape, there’s almost no better workout.

The Expert’s Verdict

Alex Honnold: “I think open-water swimming sounds fucking heinous! And in some ways dangerous, because you could frickin’ drown.”

Steph Davis: “I would not be enthusiastic if I had to do open-water swimming, because I’m not a very big fan of the ocean. If I had to do one of these sports tomorrow, I would probably be most upset about swimming.”

Scott Jurek: “Nordic skiing came to my mind right away. There’s nothing like it in terms of the feeling when you’re floating along, to grind up the uphills and cover the terrain. I think Nordic skiing is the most taxing workout.”

Rachel Atherton: “Ultrarunning! I can’t begin to imagine running for 50 miles—or 100!”

Elizabeth Fry: “I would probably say rock climbing, because there’s so much less room for error. The mental endurance and the concentration would have to be the highest there.”

Sophie Caldwell: “Objectively, I think ultrarunning would be the most difficult, because it requires so many hours of training and competing.”

Kikkan Randall: “I would have to think that open-water swimming is pretty challenging, because you are so vulnerable, and regulating your body temperature in the water can be really challenging.”

Our Verdict

1. Nordic Skiing

For our money, this is the toughest sport. It requires the endurance of ultrarunning, the sprint speed of mountain biking, the mental toughness of open water swimming, and, at times, can put skiers in situations of real exposure. And at 952 calories per hour, competitive nordic skiers burn the equivalent of a Chipotle burrito every hour. To be successful, athletes must maintain unparalleled cardiovascular fitness in addition to muscular strength and coordination.

2. Rock Climbing

Climbing requires a high degree of technical skill, and a nearly incomparable level of mental discipline and self-reliance. Unlike some other sports on this list, one cannot simply gut their way through a difficult climb—they either have the fitness to complete a certain pitch, problem, or route, or they do not. And if they don’t, the consequences can be deadly— that 145 per one million expert climbers will die from climbing-related injuries, which puts its fatality rate leagues above any other sport on this list.

3. Open-Water Swimming

This sport combines the enormous training regime of ultrarunning, the exposure of climbing, and the added element of the ocean, where one must factor in the risks of sharks and jellyfish and the tedium of changing tides. Sure, many open-water swimmers have a fail safe in the form of an escort boat, but that doesn’t detract from the absolute sufferfest that is swimming for hours (or days) at two miles-per-hour, and trying to eat 900 calories per hour in the process.

4. Downhill Mountain Biking

Like climbing, mountain biking requires a serious degree of technical competence, daring, and finesse; there’s a high barrier to entry in terms of skill required to successfully traverse a downhill course, and the consequences should one wipe out are massive (it injures more athletes than any other sport on this list). However, riders enjoy the assistance of gravity, and one doesn’t need a high level of aerobic fitness to be a good downhill rider.

5. Ultrarunning

Don’t get us wrong—running 100 miles is incredibly difficult, and being competitive in an ultra requires an almost unparalleled degree of suffering. That being said, the only requirement for beginners is to be able to run more than 26.2 miles. Running is hard, no doubt, but not as technical or energy-intensive (as measured by calories burned) as the rest of the panel.

*Did not qualify as a sport: fly-fishing, birding, spelunking.