A GAUZY APRIL MORNING in Golden, Colorado. Inside a lavish single-story office suite decked out with a big-screen TV, low-slung leather furniture, and a sprawling maple conference table, a solitary figure stands in front of a wall-size window. His hands are hooked behind his back as he gazes at a majestic view of wispy cirrus clouds arcing over the Front Range, where tan, muscular foothills back up to high, dark peaks. It’s the kind of trophy vista awarded to great entrepreneurial success, a penthouse view reserved for business moguls, politicos, and local boys who’ve cashed in on, say, the most lucrative fitness phenomenon the country has ever seen.

Bill Phillips

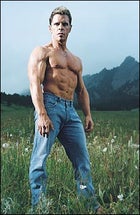

Phillips, with his 2002 Ferrari 360 Spider, strikes a pose in the mountains near Boulder, Colorado.

Phillips, with his 2002 Ferrari 360 Spider, strikes a pose in the mountains near Boulder, Colorado. SUPERSIZE IT: “Everybody has the power to change,” Phillips insists. “To be better.”

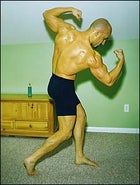

SUPERSIZE IT: “Everybody has the power to change,” Phillips insists. “To be better.” 2002 BFL Challenge Champ Thomas Phillips

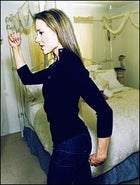

2002 BFL Challenge Champ Thomas Phillips 2002 BFL Challenge Champ Jill Augello

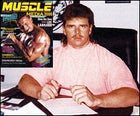

2002 BFL Challenge Champ Jill Augello Phillips at Mile High Publishing, circa 1992; inset, the debut issue of Muscle Media 2000

Phillips at Mile High Publishing, circa 1992; inset, the debut issue of Muscle Media 2000 Next up for Phillips? Writing a screenplay. “It’ll be like what Sly did with Rocky,” he says. “Inspirational.”

Next up for Phillips? Writing a screenplay. “It’ll be like what Sly did with Rocky,” he says. “Inspirational.”“Transformation is such an interesting thing,” says Bill Phillips, a former champion bodybuilder and sports-supplements impresario who can justifiably be called America’s reigning personal trainer. He turns away from the window. “You have hundreds of millions of people across the world who want to change, who try to change, but they pull their hair out because they don’t know how.”

Phillips walks to the table where I’m sitting with his manager and media handler, Jim Nagle, and takes a seat. He’s dressed in faded jeans, a navy T-shirt, and leather sandals, his short brown hair gilded with blond highlights. His arms are ropy with muscle, shaved smooth, veins braiding down to his wrists. Phillips is 39, but he looks collegiate, frattish, cool.

You might already know Phillips as the guy in a tight black tee glaring at you from the cover of his best-selling book Body-for-Life, which to date has sold 3.5 million copies in 24 languages. Or maybe you’ve heard of the company he built and eventually sold for more than $100 million, Experimental and Applied Sciences (EAS), currently the largest sports-nutrition operation in the United States. Or maybe someone you know has taken the Body-for-Life Challenge, a 12-week fitness contest that, if you believe the hype, can turn people with torsos like soft-serve cones into mini-Schwarzeneggers. If you’ve gone that route, chances are you’ve watched a Body-for-Life videotape, or belong to one of hundreds of BFL-related Internet chat groups, now atwitter about Phillips’s new book, Eating-for-Life, due out this month.

Then again, maybe you haven’t heard of Bill Phillips at all, and are still chowing down on dreadfully misproportioned piles of carbohydrates and fat, and working out halfheartedly, or misguidedly, or not at all. Yet now and then you feel the tug, standing in front of a full-length mirror, fantasizing about cannonball shoulders and chiseled biceps. Stare hard enough and you may even begin to see the ultimate badge of contemporary fitness lurking beneath the flab: six sculpted abdominal muscles, stacked above your waistband like masonry stones.

This is what the Cult of Bill vividly imagines, the holy vision BFLers work for every day. To enter this realm is to fervently believe that such a physique is not exclusive to the genetically gifted but is attainable by anybody, young or old, male or female, fat or skinny, rich or poor. All it requires, say the converted, is resolve.

Phillips swivels in his chair and looks to the window again. ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═°, we can see the broad, circular drive that rings the office complex. Today a local bike race is taking place here, and just now a pack of cyclists comes chugging up a slight rise in the road. On cue, the riders hammer past the building in a blur of color and pistoning legs.

“Everyone has the power to change, to be better,” Phillips continues quietly, thoughtfully, as if the idea is dawning on him for the first time. Nagle looks over, glancing at my notepad. This is important. Are you getting this down?

“Those riders out thereÔÇöthey’re working hard, trying to improve themselves,” Phillips says. “What makes them different from anyone else? Why people change and why they don’t is fascinating. To me, it’s the greatest mystery of life.”

PRONOUNCEMENTS LIKE THAT are a mystery as well. Are they sincere statements from a fitness visionary? Or prefab sound bites from a smart businessman who wants to seem inspiring but doesn’t quite know how?

Looking for answers to such questions, I’ve spent a year chasing Phillips and trying to get a feel for his public personaÔÇöwhich turns out to be tricky, since there isn’t one. Little has been written about him except for puff pieces extolling EAS or Body-for-Life. Even as he quietly amassed a legion of zealous followers, he materialized only at book signings, on the rare morning show, or for prescheduled online discussion. When I asked to meet him in person, his publicity people turned cagey, stoking my curiosity even more. Who was this reclusive cat whipping America into shape? He should have been huge, but no one seemed to know a thing about him.

There are reasons for thatÔÇöone being Phillips’s own awkwardness in the spotlight. “When you see him in one of his videos, he comes across as really canned,” says Michael D’Orso, 49, a nonfiction author who cowrote Body-for-Life. “And when you meet him, you can’t help but ask, ‘Is this guy for real?’ He’s a perfectionist, and there are some control-freak issues, but strip everything else away and Bill’s a philosopher at heart. He’s voraciously curious and earnest, and sometimes that doesn’t translate as well as it should.”

Another, I think, is that Phillips knows that not everything about his life story would look great on a billboard. He got his start in hardcore bodybuilding, a world where steroid use is routine, and he first made a mark with a book called the Anabolic Reference Guide, a kind of Steroids for Dummies that covered everything from how to acquire the drugs in Mexico to where you stick the needle. Phillips makes no apologies about this aspect of his pastÔÇö”It’s just what you did if you wanted to be a bodybuilder,” he saysÔÇöbut he doesn’t advertise it, either.

Whatever his motives, Phillips prefers a business plan that doesn’t require him to be out there selling and yelling like Tony LittleÔÇöa plan that fuels itself with a self-energizing network of excited customers. Body-for-Life accomplished this with gusto.

BFL’s widespread appeal has as much to do with its inviting and addictive team spirit as with its promise to deliver a fantasy figure. The workouts are brief and intense, involving three days of weight lifting alternating with three days of aerobic conditioning. The BFL diet is a bit more challenging. You’re told to eat six small meals a dayÔÇöbalancing protein, carbs, and fatÔÇöwhich in practice is a daunting chore that devotees handle by planning weekly menus, supplemented with EAS products like Myoplex protein shakes and AdvantEdge bars. You get one free day to eat what you like, but the rest of the time you draw from a spartan list of “authorized” foodsÔÇöno booze, no Ben & Jerry’s, no bacon double cheeseburgers.

When Body-for-Life hit bookstores in 1999, it was stuffed full of “Real-Life Success Stories”ÔÇöBFL-speak for before-and-after images of dramatic physical transformations. The bulked-up changelings wrote emotive testimonials about the value of goal setting, but the stories paled in comparison with the pictures. It was one thing to show photos of elite athletes who had built on their God-given superbodies, quite another to present page after page of shlumpy middle-aged professionals next to their new, sculpted selves.

“The idea to include the before-and-after pictures was Bill’s,” says David Black, 43, the literary agent who negotiated the deal between Phillips and Body-for-Life’s publisher, HarperCollins. “He had very clear ideas about what he wanted. But two other basic things made the book so popular: The program works, and it fits the harried time frame in which we all live.”

The proof is in the numbers. Last year, more than 750,000 people requested the free BFL Challenge enrollment kits. Only about 5 percent of that total see it all the way through, but even the dabblers have helped Phillips rack up substantial earnings. Though he no longer keeps royalties from the Body-for-Life book and gives large sums to charities like the Make-a-Wish Foundation, Phillips is now worth well over $100 million. On the supplement front, EAS attributes about 20 percent of its $300 million in annual revenue to Body-for-Life Challenge participants.

Who were all these people gobbling down protein and powering out reps on the incline bench? A month before I went to Golden, I traveled to New York to meet a few living, breathing BFLers, specifically Thomas Phillips (no relation to Bill) and Jill Augello, two winners from the 2002 Body-for-Life Challenge. A curious dimension of the Body-for-Life phenomenon is that very little of it is tangible. There are no mass rallies starring Bill, no infomercials, no BFL classes after work at Bally’s. It’s a virtual community, united by rah-rah chat groups in which program participants dish training tips, offer encouragement, and hash out thorny existential problems like whether to load up on Betagen before going to bed.

In Manhattan, I spent the day accompanying the champsÔÇöwho each received an EAS leather jacket, a year of free supplements, and a $50,000 cash prizeÔÇöon a citywide victory lap, a stretch limo carting us to in-store appearances at assorted vitamin shops and gourmet grocers. During the day, a crew from EAS shot footage of the winners that would later be edited, dubbed, and distributed to EAS outlets to help attract new customers. Although the winners were constantly told that this day was “all about them,” it was, in fact, mostly about the ritual baptism of EAS’s next wave of marketing infantry. Running the show was Porter Freeman, 53, a former bar manager from Orlando, Florida, who’d become a BFL champ in 1997, the first year of the contest. As the limo lurched through midtown traffic, the bronze, fit Freeman peppered the champs with well-rehearsed questions.

“Thomas, what’s the most important tool in the program?” he asked. Phillips, a stout special-ed teacher from New Jersey, thought about it while the camera rolled. Then, with a little hesitation, he said, “My body.”

Freeman turned to Augello, a lithe, blond Scot living on Long Island. “Jill, what’s the most important tool in the program?”

“My body!” she blurted.

Freeman was sandwiched between the two winners, and he slapped his hands on their knees simultaneously, shaking his head with theatrical disappointment. Phillips and Augello were rapt.

“It’s the fork!” Freeman declared. “Every time you raise food to your mouth, you’re making a decision. Is it the right one? You need to ask yourself this: Is a bite of the bait worth the pain of the hook?”

Everyone in the car nodded. We’d seen the light. But then the cameraman stopped shooting. There was a problem.

“Um,” he said, gesturing for Freeman to take a look at the rear dash, where someone had left an empty Doritos bag. Freeman snatched it and threw it on the floor.

“Was that in the shot?” he grumbled.

The cameraman nodded. Then he raised his lens again.

Freeman looked at Thomas Phillips. “Thomas,” he said, “what’s the most important tool in the program?”

“THESE ENCHILADAS ARE SO GOOD,” says Bill Phillips, scraping his plate and eyeing my stack of sweet-potato fries. “You gonna eat all those?”

Phillips, Jim Nagle, and I are eating lunch at a busy Mexican cantina on Main Street in Golden. Nobody in the restaurant seems to recognize Phillips, which makes senseÔÇöhe’s in town only six months of the year, spending the rest of the time sequestered in his two other homes, one in Maui and the other in Los Angeles, where Nagle keeps an office.

Bill was born in 1964 and raised here in Golden, the third of three children. His dad, William Phillips Sr., was a company man, working his way up the ranks at the Coors Brewing Company while taking law classes at night. He topped out as a corporate analyst at Coors, then quit to open his own law practice. The family’s middle-class ride hit a slight bump when Bill was 15 and his parents split. “It didn’t seem like that big a deal,” Phillips told me about the divorce. “We all stayed pretty close.”

Bill was distracted by his own goals. To a testosterone-addled teenager coming of age in the eighties, no path of transcendence seemed more noble than making it as a professional athlete. Inspired by Arnold Schwarzenegger and other professional lifters, Phillips decided to become a champion bodybuilder. He started lifting at 11, and by the time he reached junior high he was arguably the strongest kid in Colorado, able to crank out 265 consecutive push-ups and 52 pull-ups. In high school, he excelled in track, wrestling, football, and baseball, but team sports were only a passing flirtation. When he turned 18, riding the momentum of several state and regional power-lifting titles, Phillips headed west, to the bodybuilding foundries of Southern California.

For the next three years, from 1983 to 1986, Phillips worked out at Gold’s Gym in Venice Beach, the famous (and infamous) epicenter of the bodybuilding universe. Schwarzenegger had worked out there a decade earlier, as had Lou FerrignoÔÇöa.k.a. the Incredible Hulk. Indeed, Gold’s famous-guest list was long; among others who trained there were Muhammad Ali, Jane Fonda, and Hulk Hogan.

But getting huge wasn’t as glamourous as it may have appeared at first. In SoCal’s hypercompetitive post-Arnold atmosphere, Phillips watched his roommate start abusing steroids and descend into depression, broader drug addiction, and hospitalization. Other bodybuilders, bottom-feeders who were strapped for cash, joined what was informally known as the California Posing Club, pimping themselves out to wealthy, fetishistic clients who wanted private stripteases and sex acts, tricks that could pay as much as $5,000 a pop.

Phillips says he steered clear of the extracurriculars, but he fully embraced anabolic steroids and various supplements, at different times cycling on Deca, Andriol, Sustanon, and other drugs that helped the five-foot-eight lifter bulk up from an already brawny 185 pounds to a tottering, squarish 215. The new body armor earned Phillips moderate success as an amateur poser, but it also erased the last of his illusions.

His own use notwithstanding, Phillips was dismayed by the amount of drugs pro bodybuilders were taking to stay in the game. “You had these guys who would eat perfectly healthy diets, get plenty of sleep, stay away from booze, and then just drown themselves in huge amounts of anabolics,” he told me.

Some, including Phillips, tried to hover within acceptable levels of steroid dosage. Testosterone levels in normal males can range between 200 and 1,100 nanograms per deciliter of blood, and you can get pretty big if you spike yourself to the top end of that range. But levels among pros were off the charts, sometimes as high as 3,000 nanograms.

In 1986, at age 21, Phillips left California and moved back to Colorado, where he took classes at the University of Colorado at Denver, immersing himself in the study of exercise physiology and sports nutritionÔÇöwith an emphasis on steroid chemistry. He also started a company called Mile High Publishing and, from the basement of his mother’s home in Golden, began sending subscribers a newsletter he produced, The Anabolic Update.

Phillips was through with pro bodybuilding himself, but he knew what the muscle market needed: straight talk about training, diet, drugs, and motivation. He would take on the big boys, like Joe Weider, who he believed played a subtle shell game with the public. In magazines like Flex and Muscle & Fitness, Weider dodged the steroid topic entirely, suggesting that bodybuilders nurtured their freakish physiques solely by pumping iron and sucking down protein. Phillips knew you didn’t get there without drugs, and he intended to say so.

IN 1992, PHILLIPS MOVED OUT of Mom’s basement into a full-time office and began to broaden his reach with the launch of Muscle Media 2000, a magazine aimed at hardcore enthusiasts. The readership was already in place, thanks to the newsletter and Mile High’s 1991 publication of the Anabolic Reference Guide, his 245-page A-to-Z handbook on steroid use.

The new glossy monthly allowed Phillips to juxtapose his rather dry, technical writings on the science of bulking up with more enticing editorial contentÔÇönamely, full-color photos of snarling pros posed midlift, hair spiked, muscles at maximum bulge, entire vascular systems dilated and crackling across their skin like electrical storms.

Muscle Media 2000 took offÔÇöeventually reaching a circulation of 500,000ÔÇöas did Phillips’s mail-order sales of vitamin and protein supplements, but it brought with it new problems that come with managing a burgeoning company and its staff. According to various people who have worked for Phillips, up-close-and-personal has never been his strong suit.

“You want to know what Bill’s like?” says T. C. Luoma, 44, a former editor of MM2K who now runs a bimonthly bodybuilding magazine called Testosterone. “You know the movie Nixon? Well, NixonÔÇöthat’s Bill.”

As Luoma tells it, Phillips was a crummy manager who had trouble communicating with his employees. When he wanted something done, he would send Luoma a note or faxÔÇöeven though their offices faced each other across a hall. In 1997, when Phillips decided to overhaul the magazine and focus on mainstream fitness, in came another fax, this time telling Luoma he was fired.

Phillips has a clear response to all this: He was a very busy man. “I was managing over 300 employees,” he says. “And that didn’t afford me much time for one on one.”

Whatever his interpersonal qualities, Phillips’s empire was growing fast. By the mid-nineties, he’d made a tidy fortune selling a new protein powder called MET-Rx, courting celebrity athletes and signing them on to endorse products. But the success of protein supplements was nothing compared with a new muscle-builder that was about to hit the market: creatine.

In 1994, Phillips met a nutritional biochemist from California named Anthony Almada. Almada had come across an obscure Swedish study in the journal Clinical Science that alerted him to the muscle-building potential of a naturally occurring amino acid called creatine monohydrate. He’d started a small company called Experimental and Applied Sciences to sell it to bodybuilders, and he asked Phillips if he wanted to invest his time and energy helping market it.

Phillips jumped in, creatine took off, and for two years the men had the market cornered, selling a powdered form they named Phosphagen. “A lot of former steroid users told us, ‘Man, this feels like I’m on the juice again,’ ” says the 42-year-old Almada, who now runs a supplement consulting company in Laguna Niguel, California, called IMAGINutrition. “You could gain four to eight pounds of lean muscle a week. That’s where you got this enormous buzz and viral spread of enthusiasm. Bill saw the landscape of opportunity. Combined with his marketing wizardry, it was unstoppable.”

The arrival of creatine coincided with another windfall for the supplement biz, a controversial piece of legislation called the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act, or DSHEA. Ushered through Congress in 1994 after blitzkrieg lobbying by Utah senator Orrin HatchÔÇöwho was helping out Utah’s lucrative supplement-manufacturing sectorÔÇöDSHEA lumped nutritional supplements in with food, rather than pharmaceuticals, and thus created what amounted to a regulatory no-fly zone. With many supplements no longer subjected to expensive testing and time-consuming approval from the Food and Drug Administration, new products could hit the shelves faster than ever.

“DSHEA pretty much flung open the doors for supplement sales,” says Terry Todd, a physical-education professor at the University of Texas at Austin and an expert on the history of bodybuilding. “Unfortunately, the legislation was based on economic and political factors more than scientific ones.”

By 1997 the synergy between the magazine, which was now simply called Muscle Media, and EAS was in full swing, helping the company pull in more than $10 million a month. That year, Phillips built a new corporate headquarters in Golden, a gleaming mirrored-glass-and-steel cube that shimmered above town like a Bauhaus Xanadu. He unveiled the palatial digs with a gala event filled with sports stars like NFL Hall of Famer Marcus Allen and Broncos wide receiver Anthony Miller. He capped the party with an ostentatious fireworks display.

There was plenty to celebrate. EAS had become the most successful sports-nutrition company in America. Phillips had scored a beautiful girlfriend, a former stripper turned Playboy model named Ami Cusack. And he had just launched his Body-for-Life contestÔÇöthen called the EAS Grand Spokesperson ChampionshipÔÇöa move that would soon give rise to a commercial supernova.

“Phillips is a smart guy,” says Todd. “Writing to the steroid crowd was a dead-end road. He knew you could make a certain amount of money building monster trucks, but you could make a whole lot more building Ford F-150s.”

Indeed, business was flying, as were the social missteps that made it clear why Phillips probably worked best out of the public eye. During the party celebrating the completion of his headquarters in Golden, Phillips went up to the microphone to address his guests. According to several people who attended the event, most of the revelers ignored him until, finally, he lost it.

“If you don’t shut the fuck up,” he reportedly snapped, “I’m gonna come down there and break your fucking knees.”

It was, by all accounts, an attempt at humor rather than a fit of rage. But the crowd of friends, employees, local celebs, and families with kids and grandparents piped down all right, leaving Phillips facing them, the PA system screeching feedback.

“In the beginning, I would’ve taken a bullet for the guy,” says T. C. Luoma, who witnessed this awkward incident. “But things just got too stressful. There was no laughter in the building anymore. When Bill came in to work, your gut just knotted up.”

EAS AND MUSCLE MEDIA were twin juggernauts, but it was the Body-for-Life Challenge that really put Phillips on the map. The contest wasn’t anything newÔÇöit was derived from the crash routines bodybuilders use leading up to a pose-off. Phillips had tried out the idea a couple of years earlier, in 1995, when he advertised a similar competition in MM2K for Physique Augmentation Systems, a now-defunct division of EAS. The ad hinted at his fondness for before-and-after pictures, a potent marketing gimmick that spun all the way back to 1950, when Charles Atlas created his cartoon narrative about the scrawny guy who gets his babe snatched away by the buff beach bully, bulks up, and then wins her back.

Body-for-Life advanced the form with more sophisticated workouts and diet, and it did so at a fortuitous time. Headlines everywhere were screaming about escalating health issues like obesity, increasing rates of adult diabetes, and heart disease, problems that are still on the rise. Just as important, Phillips was playing on deep-seated emotional insecurities: Were we hot? Probably not. And it didn’t hurt that the age of the Superbod had descended, kicking off with Arnold’s stardom and growing fast to include a platoon of representatives like Sylvester Stallone, Fabio, Jean-Claude Van Damme, and, more recently, Vin Diesel and the Rock. The secretÔÇönot that it was very well keptÔÇöwas bodybuilding. When Sly wanted to bulk up for his role in Cliffhanger, he turned to Phillips for a training plan. Demi Moore’s one-arm push-ups in G.I. Jane? Phillips was behind those, too.

Body-for-Life promised a celebrity physique to anyone willing to commit themselves to 12 weeks of weight lifting and sweaty bouts on the treadmill. But the hardest part wasn’t the exerciseÔÇöit was, and is, the diet. “The program is like 60-40, food to exercise,” says Jack Quinlan, a 37-year-old BFLer I met during the champions’ tour in New York.

This is where diet supplements come in. Participants who enroll in the Body-for-Life Challenge are required to use at least two different EAS products during the contest, the most popular being Myoplex shakes and bars. Never mind that the bars taste like an eraser and the shakes like Milk of Magnesia; they offer nutrient density you just can’t get from the glass case at Starbucks. But, hey, no pressure: You can either plan, prepare, and diligently consume whole-foods meals six times a day, six days a week…or you can go to a GNC, stock up on supps, and keep them conveniently on hand.

Is it worth it? Quinlan, a Body-for-Life runner-up in 2002, thinks so, and says that eating the BFL way is pretty economical. “I was skeptical, too,” he says. “I didn’t want to look like a bodybuilder. My boss had talked me into doing the New York City Marathon, and I was 30 pounds overweight and hadn’t put on running shoes in a year. I was desperate.”

When Quinlan started Body-for-Life, he was pasty and plump. But in his “after” photo, he’s slim and copper-colored, posing sideways, hands clenched by his hip, one knee cocked forward.

“It’s hardÔÇöyou have to give up a lotÔÇöbut it works,” he says, almost pleadingly. “What, are you gonna fault these guys for trying to make a buck off me? Hey, welcome to America.”

IN GOLDEN, AS WE finish lunch at the cantina, Phillips is loosening up, divulging a little more about himself. He’s currently single, though he thinks seriously these days about settling down. He’d like to host a TV show, and he’s been developing a proposal that will feature him interviewing a steady parade of folks who have gone through successful transformations.

Lately, he’s been consumed by his new books. In addition to Eating-for-Life, two more are slated for quick release: The Eating-for-Life Cookbook, a compendium of recipes due out this fall, and Energy-for-Life, which presents a Tony Robbins-esque plan for harnessing emotional power, scheduled to hit stores a year from now. Phillips is publishing the books himself, rather than through HarperCollins, because, he says, “New York is too slow.” With the Atkins diet books topping best-seller lists, Phillips is anxious to enlighten devotees of this protein-heavy regimen about their misinformed ways.

“The Atkins diet is stupid,” Phillips says. “It’s not low-carb; it’s no-carb. But people are flocking to it. Of course you’re going to lose weight, since every gram of carbohydrate stores three grams of water. But do you want your diet to be without carbs? What kind of fuel are we burning right now, just sitting here talking? It’s not protein or fat. It’s carbohydrates. That’s what our brains use for fuel. You want to not have any brain fuel?”

As if we’re playing out a scene from Body-for-Life Theater, the waitress reappears and sets down a tempting basket of warm sopapillasÔÇöfried breadÔÇöand a honey bear. Phillips, Nagle, and I stare at it for a minute, then Nagle slides the basket to the edge of the table. “It’s like we’re living on Temptation Island,” Phillips continues. “My house is only a few miles from my office, and I pass eight fast-food places on the way to work. There’s a multibillion-dollar industry out there that’s banking on the fact that you won’t be able to resist.”

He drums his fingers on the table.

“We’re eating and eating and eating, but we’re starving, because we aren’t getting the nutrients we need. Think of Golden. It used to be a mining town. The first settlers came here and they’d dig through mountains of dirt to find one little scrap of gold. That’s what our bodies do. Out of all the junk we’re putting in it, we’re asking our body to go through and find the gold it needs to fuel our metabolism and our mind and our muscles.”

Phillips, the BFLers, EAS employeesÔÇöthey’ll all tell you the same thing: Body-for-Life isn’t just about getting huge and cut. And, in many ways, they’re right. The regimen is widely adjustable, and EAS employs a large call-center staff to help youÔÇö24/7 and free of chargeÔÇöfine-tune the program to your specific needs.

At the end of the day, what they really want you to understand is that BFL is not just a workout or a dietÔÇöit’s a lifestyle, a game plan for coping with America’s nutritionally ravaged landscape and waning physical activity. The bait is the promise of a beautiful body, but the larger thrust, the implied guarantee that accompanies your new physique, is that you’ll also enjoy emotional health, increased vitality, better sex, and inner peace.

That’s a tall order for any fitness plan, even one as malleable as Body-for-Life. True, it will help you sculpt your appearance, but therein lie its limitations. If the program is hardÔÇöand it is if you stick to the rulesÔÇöit’s largely because your approach to food and exercise has to become as rigorous, focused, and disciplined as your workday. That leaves precious little room for spontaneous culinary adventures, happy-hour margaritas, three-day surf safaris, or mountain-biking epics. Body-for-Life is a utilitarian solution to many of our fitness woes, but even Phillips agrees it’s not the final answer.

“I know that 50 percent of everything I’m doing isn’t working,” he says. “But I want to know which 50 percent. People who do Body-for-Life help me. I learn from them. That’s why I love doing what I do.”

WITH THAT, PHILLIPS excuses himself and slips out of the booth. As soon as he’s gone, Nagle leans over the table and says, almost whispering, “He’s really painfully shy.”

This is our first moment together without his boss around, and it seems that Nagle wants to explain, if obtusely, why he was so evasive when I first asked to interview Phillips. Not that I doubt what he’s just told me: Everything I’ve observed or learned about PhillipsÔÇöfrom his delicate handshake to his downcast eyes and quiet voiceÔÇöhas told me that this is a guy who’s far more comfortable hanging out with his own ideas than with strangers.

In that light, his Oz-like orchestration of Body-for-Life suddenly makes sense. Phillips is shy, sort of, and the shyness has helped drive his uniquely successful style, allowing him to develop a self-hyping system of exercise, diet, and inspiration, then deliver it in a package that is accessible, highly desirable, and perfectly timed. This is the formula that distinguishes him from the others who’ve built careers helping Americans shape up: Tony Little, Billy Blanks, Chuck Norris, Denise Austin, Robert Atkins, Barry Sears, Bob Greene. They offer a workout, or a diet, or motivation, but not all three, artfully spun together in a plan so simple and obvious that its only truly miraculous quality is that it didn’t happen sooner.

Above all, the triumph of Body-for-Life freed Phillips to pursue the ultimate question: What, in the end, makes us change? Bodybuilding had unveiled a foolproof plan for working out and feeding yourself, but those aspects were just physiology, the mechanics of alteration; they weren’t the source of it. He mastered the science, but it deposited him at the foot of something much larger and more complicated.

Here loomed his great mystery, the wellspring of transformation. The foundation was emotional, not physical or intellectual, and it required Phillips to keep generating new means of inspiration, to “reach people’s hearts instead of their heads.” He was no longer just a coach; he now saw himself as a sage.

“I want to touch,” Phillips had told me earlier, “not teach.”

Phillips returns, and Nagle looks at his watch. “So what’s next, after the books?” I ask.

“Well,” says Phillips. “I’d like to write a screenplayÔÇöI will write a screenplay. Something like what Sly did with Rocky.”

“Any ideas?”

“I know it’ll be a success story of some kind. Inspirational.”

“Based on your life? Like 8 Mile?”

“I don’t know,” he says. “Maybe. I didn’t see that one.”

“We need to go,” says Nagle.

We stroll out into the bright Colorado sunshine and walk to Phillips’s new ride, a hulking black Cadillac Escalade SUV, fully kitted with leather upholstery, in-dash satellite TV, and wireless Internet.

Phillips halts. “How about this,” he says. “Small-town kidÔÇönot me, someone elseÔÇögrows up and invents something that helps everyone in the country live healthier, better lives.”

He absently wipes a smudge off the door of the giant, glistening car.

“Don’t you think that would make a great transformation story?”