Next to the “SHOP” tab on�� of upstart Swedish sports-drink maker Maurten, there’s another tab that says “UNOFFICIAL SHOP.” Click on it, and you can order gels and sachets of drink mix in plain, unmarked foil packages. The intended market, the company says, is elite athletes who are sponsored by other companies but still “want to benefit from the Maurten hydrogel technology without breaking contracts”—sort of like the reports of elite runners racing in Nike’s Vaporfly shoes .

Full credit to Maurten for a cheeky campaign, and for the unbelievable rapidity with which their products have swept through the endurance world. Eliud Kipchoge is one of ��who swear by them. Geoffrey Kamworor even drank Maurten during his recent half-marathon world record, since elite runners rarely drink during such a short event. And the word on the street among recreational and age-group athletes is also resoundingly positive, from what I can tell. Everyone loves the stuff.

There’s just one thing missing: evidence that Maurten is really any different from all the other sports drinks on the market. Maurten’s main claim is that two key ingredients, pectin and sodium alginate, react with the acidity of the stomach to form a hydrogel. This gel basically encapsulates the drink’s carbohydrates, “hiding” them from gut sensors that would otherwise detect their presence and trigger gastrointestinal discomfort. The gel-covered carbs then pass into your intestine, where the hydrogel reliquifies and allows the carbohydrates to be absorbed. The result, in theory, is that you can get more energy into your system without triggering GI problems compared to a normal drink.

It’s a good story, but how do we know that’s what really happens? I first corresponded with Maurten representatives back in March 2017, when I was told about ongoing external research that was expected to be complete in November of that year. I heard the same thing the following year, with research expected that autumn. More than two years later, I’m still waiting.

In the meantime, others have started testing Maurten. Earlier this year, I reported on an presented at the American College of Sports Medicine annual meeting which found that Maurten was emptied out of the stomach more rapidly than a comparable drink without the hydrogel ingredients. Half of the ingested drink was gone after 21.2 minutes compared to 36.3 minutes, which jives with the idea that you’re less likely to feel bloated and have an upset stomach with the more rapidly processed hydrogel drink. (That study came from researchers at the universities of Cape Town, Stirling, and Brighton; although the authors made no conflict-of-interest disclosures, Cape Town and Brighton are listed on the Maurten website as collaborators.)

Those results are interesting, but stomach-emptying speed isn’t the ultimate outcome most of us are concerned with. So it’s good—and long overdue—to see two new studies that test more practical outcomes.

The first, ��in the International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism by a group of researchers led by Alan McCubbin at Monash University in Australia, put nine male runners through three hours of steady running followed by a progressively accelerating run to exhaustion that took about 12 minutes. The volunteers did this protocol twice, once with Maurten and once with a control drink that contained the same flavors and ingredients (most notably the two carbohydrates, maltodextrin and fructose) in the same ratios, with the exception of the hydrogel ingredients, pectin and sodium alginate.

The researchers collected all sorts of data during the runs: blood glucose levels, rates of carbohydrate and fat burning, symptoms of GI��discomfort, and of course performance in the time-to-exhaustion test. Fortunately, the results are pretty easy to sum up: there were no detectable differences between the two groups. Every runner had at least some mild GI symptoms; one runner had severe symptoms (meaning they were rated as at least 5 on a 10-point scale) with Maurten, while two had severe symptoms with the control.

The , published in the European Journal of Applied Physiology by researchers at Virginia Military Institute, Elon University, and James Madison University, looked at cyclists instead of runners. In McCubbin’s study, the three-hour run was at 60 percent of VO2max, which is not all that hard, so the VMI team, led by Daniel Baur, wanted to see whether higher intensities might trigger more GI problems. McCubbin’s study also featured a relatively manageable drinking rate of 500 milliliters (16.9 ounces) per hour; Baur’s team doubled that to a liter an hour, which again makes GI issues more likely.

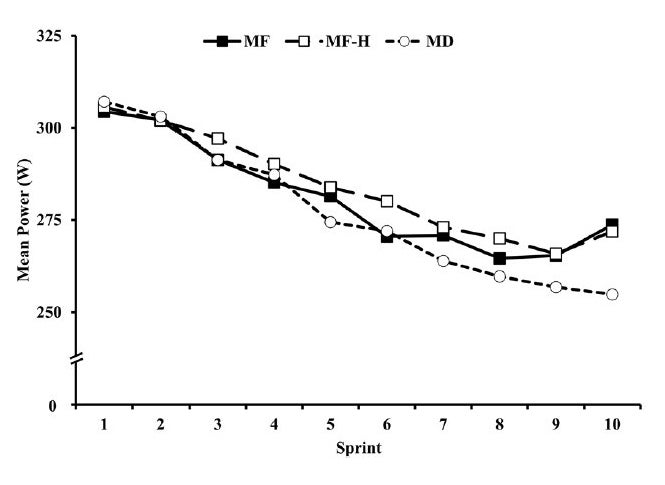

The nine subjects (all male, once again) did a 5-minute warm-up; 55��minutes��at a moderate pace (50 percent of power at VO2max); two sets of 4 x 2–minute��intervals with 2��minutes��between reps and 5��minutes between sets; 5 minutes at a moderate pace; and finally 10 all-out sprints lasting 2 to 3 minutes each with 5 to 6 minutes of easy riding between each one.

The conclusions are once again straightforward: no significant differences between the Maurten group and the control drinks in performance (i.e. the power output in the sprints) or in subjective ratings of GI distress and effort. On average, GI symptoms started at “extremely weak” and progressed to “weak or mild,” and even during the sprints didn’t exceed “moderate.”

There were actually two control drinks here: one contained a mix of maltodextrin and fructose, like Maurten, and the other contained only maltodextrin. Previous research has shown that you can absorb carbohydrates more rapidly when you have two different types, but in this case the carb mixes didn’t have any obvious advantage. The only hint comes if you look at the power output in the ten sprints, where the maltodextrin-only group (white circles) seems to fade in the final few sprints compared to the maltodextrin-fructose control (black squares) and Maurten (white squares). That difference wasn’t statistically significant, though.

Taken together, these studies aren’t encouraging for Maurten fans. Whether it’s cycling or running, steady pace or intervals, low volume or high volume of drinking, there’s no apparent advantage to the hydrogel. Of course, there are all sorts of possible caveats, which both papers consider at length in their discussion sections: the rate of drinking, the duration and intensity of exercise, the carbohydrate dose, and so on. And the sample sizes in both studies are small, leaving open the possibility that they simply weren’t able to pick up the differences between drinks.

The real crux of the matter, though, is this: does an artificial test in a laboratory, particularly one that starts with a bunch of easy running or riding before finishing with a relatively short dose of high intensity, really replicate the grueling ordeal of a competitive marathon? Even leaving aside the differences in pace and motivation, the nerves associated with competition seem to play a big role in the stomach problems marathoners often encounter. Maurten didn’t reduce GI symptoms in these studies, but almost none of the participants actually experienced severe symptoms.

So to me, the door is still open. I’m not ready to completely dismiss the overwhelmingly positive word-of-mouth I’ve heard about Maurten. Runners and cyclists and triathletes know their bodies pretty well. And Eliud Kipchoge can’t be wrong, can he? On the other hand, we’re all human and susceptible to the power of suggestion. Before I believe that this drink is so good that elite athletes should break their contracts to get it, I’d like to see some data.

My book, , with a foreword by Malcolm Gladwell, is now available. For more, join me on and , and sign up for the Sweat Science .��